From the mid-1960s until the middle of the following decade, HMV Records (New Zealand) Limited and its successor EMI Records (New Zealand) Limited, the biggest record company in the country, employed the services of an unique – for New Zealand – in-house production team tasked with making records for their various labels. The team would record over 300 singles and were responsible for countless hit records and New Zealand classics including seven Loxene Golden Disc awards. More than that, they (with Auckland's Zodiac label) also advanced the art of recording in New Zealand to a standard equal to that available in the rest of the world at the time. Alan Galbraith was a key part of that production team. This is his story.

From the time I first set foot in HMV’s studio in Wakefield Street, Wellington I was in awe. This was in 1966 as frontman for Sounds Unlimited, a band that recorded several singles under producer Nick Karavias, who also worked with The Avengers.

At that time we worked on 2-track tape machines through an 8-channel desk built by engineer Frank Douglas. Band tracks were recorded straight (live) to stereo or mono with usually only one overdub for vocals, sweetening and maybe percussion.

The Avengers outside the HMV building in Wakefield Street, Wellington

There was an old, locally made echo plate down the hall and delay came courtesy of an auxiliary tape machine. Phasing effects were achieved by running two tapes together in sync, then slowing one down with your hand to put the tracks slightly out of phase. Pretty hit and miss but it worked okay – listen to Simple Image or early Fourmyula, or even Shane’s ‘Saint Paul’.

Almost immediately I knew there had to be a place in all of this for me, but until then, I had no idea that there was such a thing as a “producer”. I knew about engineers and arrangers, but the role of the producer seemed tailormade to someone like me, with lots of ideas and a ton of enthusiasm, but no real training.

I soon spent every available moment working in the studio as a musician, singer, composer – whatever was required, with or without pay. I would have scrubbed the floors if that’s what it took. I soon got to see how it was all done.

A heyday for local recording

During the sixties, HMV Studios in Wellington was definitely the place to record. They had a solid track history with local music, and by the early sixties they had most of the big acts of the day on their books. Although owned by HMV, (a local offshoot of EMI UK) the studio was also home to artists from the other big labels.

Alan Galbraith in the studio, 1970

This was a time when record companies funded most recordings. Although there were several independents making successful records, all of the mainstream pop acts were signed to major labels. In a lot of cases, there were no real contracts or if there were, they were fairly basic and largely in favour of the record company.

I guess you could argue that, as they were paying for it and the chances of turning a profit were pretty slim, it was a reasonable practice. It only really became an issue when an artist became very successful, got a deal overseas, or wanted to make other plans.

For most of us would be pop stars, all that mattered was that we could actually make a record, hear it on the radio, and tell everyone we had a record deal.

For most of us would be pop stars, all that mattered was that we could actually make a record, hear it on the radio, and tell everyone we had a record deal. We never expected to make money, but it helped get us the publicity we needed to get better live gigs and more fans. In that respect, maybe not much has changed.

A lot of artists went through the HMV studio in the sixties, some good, some fairly average. But we all got to have a go, and the record companies tried their best to make it work. The reality was, however, that we were all just learning and when I went to work in the UK in the early 70s I soon understood how amateurish our industry really was.

Competition was fierce, but not just between the record labels: there was also a strong Auckland vs Wellington thing going on. My take on it was that Wellington was the home of producer-driven commercial pop and hit records, whereas Auckland seemed to allow artists more control and was therefore a bit more eclectic. I worked happily in both cities and with artists from both ends of the country.

After producer Nick Karavias’ success with The Avengers HMV appointed their first full time staff producer, Howard Gable, who built the HMV stable with Simple Image, The Fourmyula, Yolande Gibson, Mr Lee Grant and Allison Durbin. These were heady days for HMV and the company was keen to ramp it up even more. The local acts were now big business, although none of them sold significantly overseas.

My turn

At this point I was desperate to join HMV as a staff producer. However I was living in Auckland at the time of Howard Gable’s departure and was pipped to the post for the job in late 1968 by Peter Dawkins.

I worked with Peter in the studio both as a solo recording artist and session musician and we became good friends. He was a clever guy who had a real knack for picking hit material for his artists and having the determination to see his ideas through. Unfortunately, this sometimes caused some aggravation with the artists but usually, when it came to picking the hits, Peter was right.

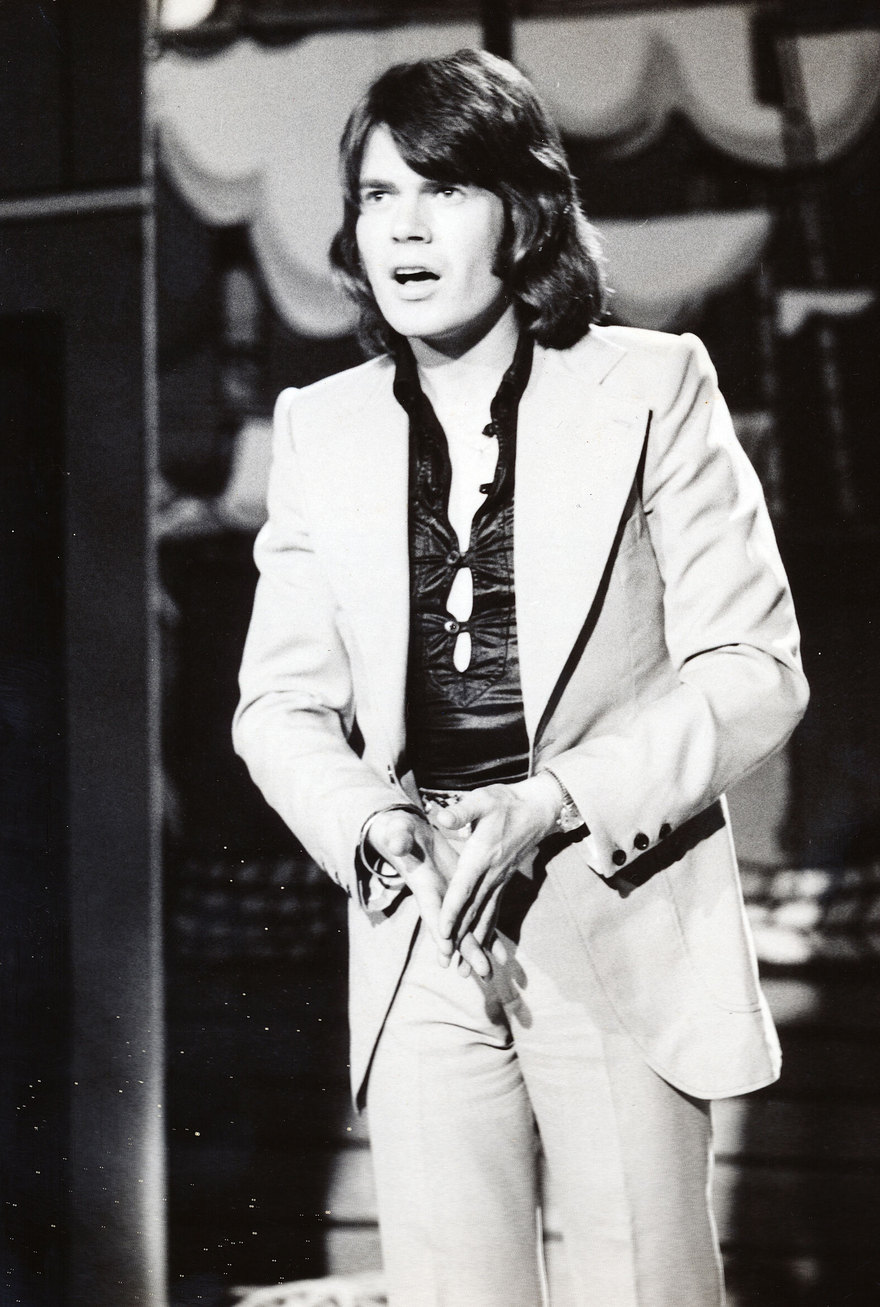

Craig Scott

This, of course, was a time when hit singles were what drove the business. It was also a time when songwriters and performers were not always one and the same. Not a lot of recording artists were yet writing their own music – particularly in this part of the world.

Most of us wrote a little bit and had songs recorded as B-sides or album tracks, but we weren’t writing the hits. We mostly depended on tracks from overseas music publishers, or songs that were neglected by local record companies. The idea that we were given songs that were hits overseas to record before the opposition labels could get them out was a bit of a myth.

The person who controlled this process was the producer, or A&R man (Artist and Repertoire, and yes, usually a bloke). It was a producer driven industry: they found the artists, found the songs, supervised the arrangements, directed the sessions, oversaw the mastering, and handled most of the promotion.

Ramping it up

So, in 1969 I joined HMV as a staff producer alongside Peter Dawkins. It was a brave move to have two full-time producers working the local scene, but it wasn’t all about making pop hit records.

Peter and I also worked with accordion bands, Māori cultural groups, brass bands, the Symphony Orchestra, country and western acts, folk clubs, comedy albums, and everything in between. It may have seemed tedious at the time, but what it added to my musical knowledge was invaluable.

During this time, HMV studio was upgraded to 4-track, then a later 8-track. We still had Frank Douglas’s old desk and a pair of 12-inch Goodmans for monitoring, but it all seemed to work. There was something magic in that studio despite its apparent lack of sophistication.

Peter had great success in the late 60s to early 70s producing hits with Craig Scott, The Fourmyula, Shane, Hogsnort Rupert, Headband and many others. I did the same with the Kal-Q-Lated Risk, teenage star David Curtis, Nash Chase, Brendan Dugan, and Highway.

- Jim Lawrie Collection

In late 1971 egos intervened. Peter and I were creating hits (and money) for HMV but not getting very well rewarded. We started making plans to conquer the world. Peter went off to join EMI Australia and I left for London.

A new era

After not conquering the world during a brief stint at EMI in London, I returned in 1973 to my role as producer at HMV, soon to be re-branded EMI New Zealand. Armed with a dangerous amount of new knowledge, I was more determined than ever to shake some trees.

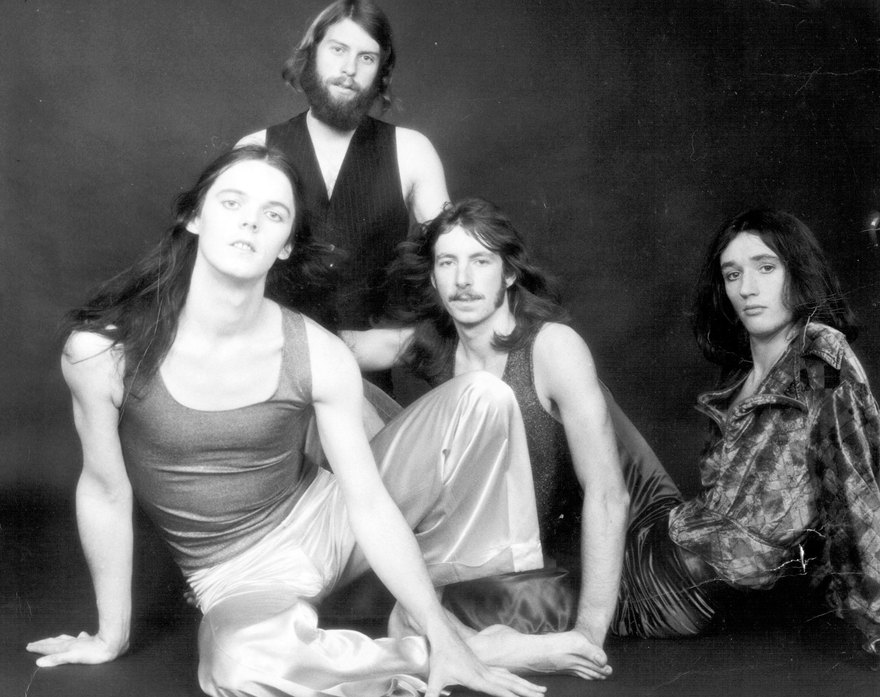

Space Waltz - the first lineup without Eddie Rayner

My self-imposed mission was to build a stable of artists that could work together in the studio as well as live on stage, to foster some songwriting talent, and start building what I called “New Zealand music to the world”. The concept was loosely based on the Stax Records model in the USA.

We started by putting together Rockinghorse as the EMI house band. Carl Evensen and Wayne Mason were ex-Fourmyula, Bruce Robinson was ex-Shane and The Pleazers, Clinton Brown and Keith Norris were a tight rhythm section I had worked with previously in Rebirth. Essentially they were a country rock band, but with solid studio experience and good all round musicality.

Rockinghorse

Bruce had played in an Auckland outfit called Face with Mark Williams and recommended him as a potential star, so after a quick audition, he joined us. I had always wanted to work with the Yandall Sisters, who harmonised with the kind of soul that only real sisters can produce. Our merry band was later joined by Sharon O’Neill and the set up was complete, except that Sharon had other plans and left early to find her own success.

Another integral member of the team was pianist and musical arranger Dave Fraser, although we also had arrangements written by Auckland musicians Mike Harvey and Julian Lee.

The sessions were mostly good, but often fraught. The studio techs still had a bit of a public service approach and would down tools at morning and afternoon tea time, and not want to work nights. Despite that, Frank Douglas, Peter Hitchcock and Michael Grafton-Green were talented and endlessly inventive engineers who contributed a lot to what we did.

Different strokes

How we went about choosing material for the artists differed wildly. Rockinghorse wrote all of their songs and had a proven track record in that regard. Mark Williams, on the other hand, was not writing at that point and always seemed to be not quite sure what direction he wanted to go in. I basically chose what he would record, arranged it, and steered the whole thing along.

Mark Williams in the EMI Studio, Lower Hutt 1976, with engineer Peter Hitchcock

Mark wasn’t always happy with the material I chose. I recall that he hated ‘Yesterday Was Just The Beginning Of My Life’, which is not surprising considering the demo I had from Vanda and Young was pretty basic. To his eternal credit, however, Mark was a superb stylist and managed to find a way to make most of the songs I selected his own, with that magical soul voice he was blessed with.

The Yandall Sisters and I worked closely together on their material, and they did like to be pushed into things they wouldn’t normally attempt. I think getting them to do the Eagles ‘Desperado’ was a bit cheeky, but they pulled it off. Mostly, however, they were more comfortable with the Philadelphia styled pop-soul material, as was Mark.

The interesting combination throughout was the mix of soft soul with the tight country rock of Rockinghorse. I thought I had stumbled on a great new sound but soon realised this was going on all over the USA, and if I was going to take NZ music to the world, I might have to take a new approach.

Hitsville Wellington

The mid-70s proved to be a boom for EMI New Zealand. Mark Williams recorded several top hits, and three albums including one of all New Zealand compositions. Rockinghorse made two albums and a Top 10 hit with ‘Thru The Southern Moonlight’. The Yandalls made one album and scored two Top 10 hits. In both 1975 and 1976 I was the proud recipient the NZ Producer of the Year Award.

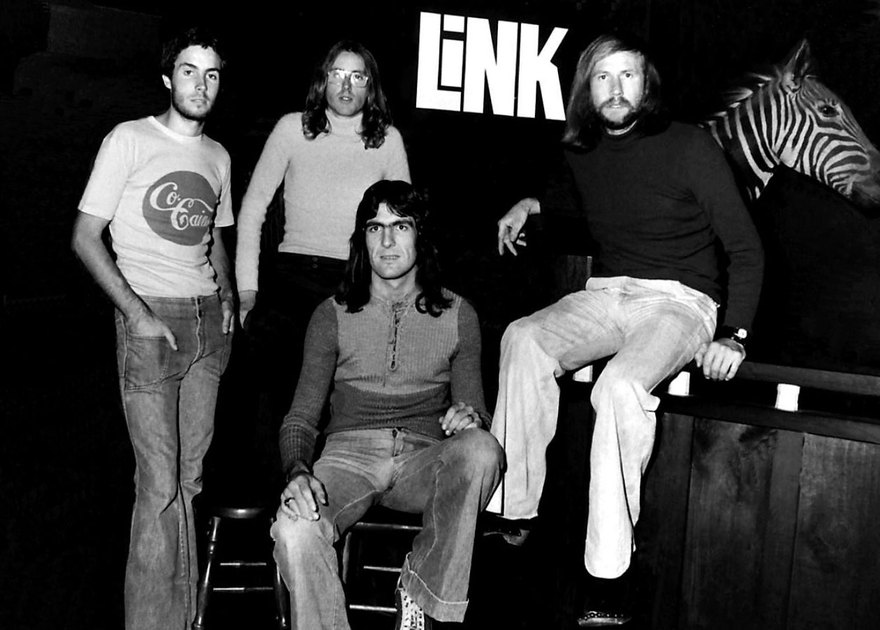

As well as the main artist stable, we had hits with Space Waltz, Link, The Hammond Family, Annie Whittle, Craig Scott and Anna Leah. I also recorded Doctor Tree, Fred Dagg, Corben Simpson and BLERTA. In 1976 we even travelled south to record The Hollies live in the Christchurch Town Hall. You certainly can’t say that we didn’t embrace diversity!

Link, taken in Adam's Apple nightclub, Christchurch February 1975 - Photo by Kevin Hill

In the midst of all this the EMI studio was relocated to Lower Hutt in 1976 and a new 16-track Neve console was installed. The first album to be recorded there was Mark Williams' Taking It All In Stride (1977), followed shortly after by the soundtrack to Roger Donaldson’s first feature film, Sleeping Dogs (1977).

About this time, I started to get the feeling that the local industry was getting a bit tired. The breweries had taken over the live scene and began to squeeze the life out of original music. There was a new groundswell happening in Auckland, but I had the urge to move on. Then one day I got a call from my old mate Peter Dawkins who asked me to join him at CBS Australia. I moved to Sydney in September 1977.

But that’s another story.

–

Alan Galbraith's credits at Discogs.

Truth and legend – The HMV and EMI recording studios and pressing plant