“We played just for the love of it,” Brown remembers, “but it wasn’t long before paid engagements came along and it was pretty good money for a schoolboy; in fact, I gave up my paper round.”

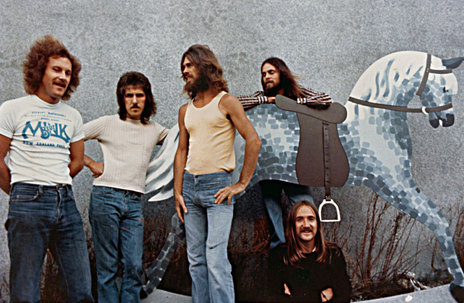

In 1967 The Society auditioned for promoter Ken Cooper and the following week they supported The Avengers at The Place, Cooper’s Wellington city nightspot. It was at The Place where The Society mostly played and it was where Clinton Brown first met guitarist Mike Farrell. In 1969 Brown, Norris, Farrell and keyboardist Warren Willis formed Rebirth.

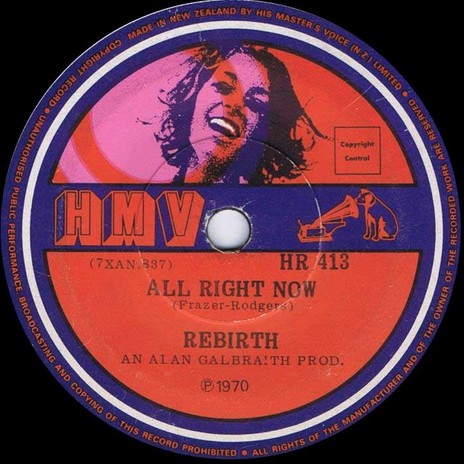

Rebirth played regularly at Dave Day’s backstreet “underground” club, Lucifers, and recorded two singles for HMV, ‘To Love You’ (written by Farrell) and a version of Free’s ‘Alright Now’. Neither release made an impression, and the band didn’t last long.

“We all had day jobs,” says Brown. “My first job – in fact my only day job – was at Viking Records. I was the export manager, packing off records to the Pacific Islands. Barry Coburn worked there at the same time and I always got along very well with (Viking boss) Murdoch Riley. I regularly applied for Fridays off for out-of-town gigs but after two to three years my immediate boss, Keith Southern, gave me an ultimatum – either sell the music or play the music.”

Clinton Brown has been a full-time musician since.

In 1970 Brown and Norris were summoned to Melbourne by guitarist Milton Parker, who’d bellied up across the Tasman after leaving the band Freshwater. It wasn’t a successful move. The new group, which also featured NZ saxophonist Dave Brown, was named Tangent.

“It was a struggle,” Clint recalls. “Billy Thorpe was huge at the time and it was those days when the audience just stood there, swaying, eyes closed. We fitted in okay, the other bands liked us but we played for peanuts, waiting for the break that never came.”

The Melbourne sojourn lasted seven to eight months and the band was so broke that they couldn’t afford to get back to New Zealand. After approaching the Chandris Line, they were contracted to play their way back to Wellington. “It was on board the Ellinis and it was a very nasty voyage. In fact, we didn’t play at all, Milton was so sick he couldn’t leave the cabin.”

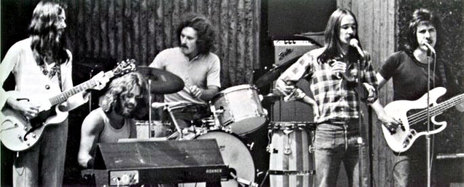

Back in Wellington Brown and Norris teamed up with Kevin Bayley and Rick White (guitars) and Steve McDonald (vocals, keyboards). Named Taylor, they played the Wellington Buck-A-Head concerts, were popular on the universities circuit and scored a residency at a new Auckland nightspot, John’s Place. In 1972 PolyGram released a self-titled album (now a collector’s item)and shortly after they disbanded.

Rockinghorse lasted five years, recorded two albums, enjoyed a genuine hit single, 1974’s ‘Thru The Southern Moonlight’.

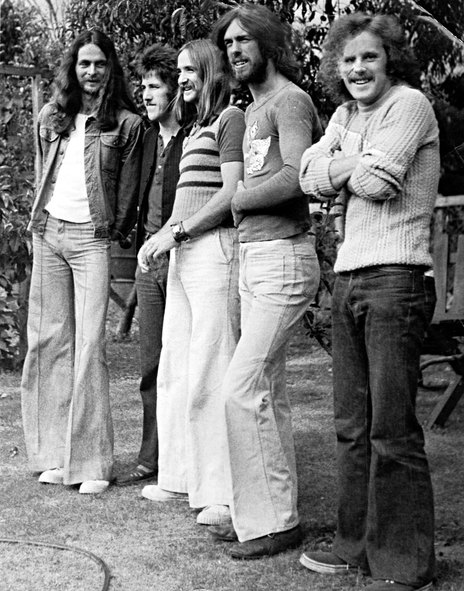

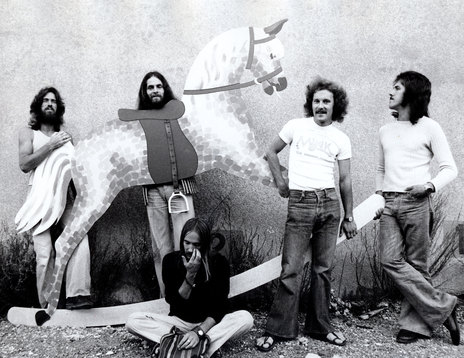

Returning to Wellington, Brown and Norris provided the rhythm section for what amounted to a New Zealand “supergroup”, Rockinghorse, with vocalist Carl Evensen and pianist Wayne Mason (both ex-The Fourmyula) and guitarist Bruce Robinson. Their pedigree alone earned them a recording contract with EMI and in-house producer Alan Galbraith employed them as resident band, backing the likes of Mark Williams, The Yandall Sisters, Prince Tui Teka and Annie Whittle. They were also on call to back solo artists (a pre-Mi-Sex Steve Gilpin, Hayden Wood) for Television New Zealand.

Rockinghorse lasted five years, recorded two albums, enjoyed a genuine hit single (1974’s ‘Thru The Southern Moonlight’) and played to packed theatres on a national tour with Mark Williams and The Yandalls.

Brown says, “Those early years were full-on, we were either on the road or in the studio. EMI bought us a Transit van and we even had sponsorship with Lee Cooper Jeans. We played universities, clubs, pubs and theatres. In 1975 we were named Band Of The Year, which is when it all started to come unstuck.”

In November 1975 the RATAs (the Recording Arts Talent Awards, precursor to the RIANZ/ Tui Awards), were held at TVNZ’s Wellington studios, pre-recorded, a low-key daytime affair. Rockinghorse picked up Best Group and Best Single (for ‘Thru The Southern Moonlight’).

“We were pissed on cheap champagne, full of ourselves. Best Group! And then someone said, ‘aren’t we playing tonight?’ Which we were, at the Lion Tavern. By this stage, the Lion Breweries circuit was our bread-and-butter. So we did the gig and it was awful. The manager came up to us afterwards, very unhappy, and warned us about performing pissed. I don’t know who started it, I think it was Carl, but one of the boys said something about being New Zealand’s top group and who needs you anyway, that sort of stuff, the piss talking. The next day Alan Galbraith told us said that a directive from the top (National Entertainments Manager Richard Holden) instructed all hotel managers not to employ us, and our income plummeted overnight.”

1976 brought no reprieve – in May Alan Galbraith left EMI and without his support, Rockinghorse failed to retain house band residency. There was no follow-up hit single and when the band’s second album, Grand Affaire, failed to sell they were without a record company.

They struggled on, although with regular line-up changes. Barry Coburn briefly managed the band, releasing a single, ‘You Can Love’, on his White Cloud label, and mending some of the damage done with Lion Breweries. In 1977 the Clinton Brown-Keith Norris partnership finally came to an end when Norris hung up his sticks. They had played together in five bands for over 12 years.

In 1978 a business collective, including Clint Brown and current Rockinghorse manager Danny Ryan, leased premises on Courtenay Place, essentially to give Rockinghorse a venue to play. They came up with a good name too – The Last Resort.

Brown: “It started out as a venue for the band but not for long. Rockinghorse itself split up within a few months. Most top New Zealand acts of the era played there – Crocodiles, Mockers, Midge Marsden, Sam Hunt and Gary McCormick, all sorts. We sort of based it on Charley Gray’s Island Of Real in Auckland but we soon realised that it was hard making a buck with coffee and chocolate cake. We needed a liquor licence but that never happened.”

When Auckland punk band The Terrorways, accompanied by their boot boy following, played The Last Resort, the toilets were smashed and local punters stood over. “When the punk thing came along and things got nasty, it was the beginning of the end for us really . . .”

In 1981 Sharon O’Neill recruited Brown as studio and tour band bassist.

In 1980 Sharon O’Neill recruited Brown as studio and tour band bassist. He appeared on all of O’Neill’s recordings over the next two years, including the Smash Palace soundtrack. O’Neill and band (including Dave Dobbyn, post-Th’ Dudes and pre-DD Smash) were Sydney-based for a concerted attack on the Australian market. And there was a high profile national tour supporting Boz Scaggs but in 1983 Clinton Brown was back in Wellington playing with the Dennis O’Brien Band. Over the next five years he played in residencies at the Romney Arms, 1860 Tavern, and the Chips and Exchequers nightclubs; he was very much in-demand as a studio musician.

Despite the ups and downs of his career, Brown was content enough. He was simultaneously playing in two, sometimes three bands, and was bassist of choice at Marmalade Studios. “I was making a living, married, bought a house, always working. I was reasonably comfortable and living in Wellington, my hometown. And then Barry Saunders called me, inviting me to join The Warratahs.”

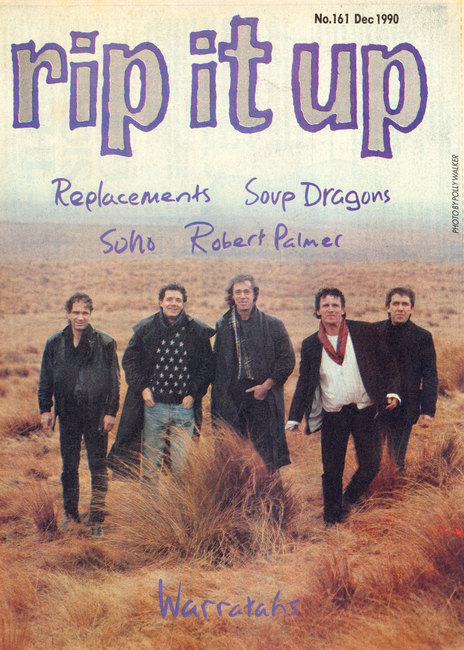

In 1988 The Warratahs had outgrown their Cricketers Arms residency and had recorded their debut album but now needed a new bassist. Over the next six years Clinton Brown toured almost incessantly with The Warratahs, when not recording, and not just New Zealand but Australia several times.

Brown had a history with the key band members. Both Barry Saunders and Wayne Mason had been in Rockinghorse. “Rockinghorse played mostly country rock but this was straight country. I never thought that I’d ever play country music festivals in Gore and Tamworth!”

OVER THE NEXT SIX YEARS CLINTON BROWN TOURED ALMOST INCESSANTLY WITH THE WARRATAHS.

The Warratahs disbanded in 1994 and Brown relocated to Auckland as a member of The Greg Johnson Set, but the following year Barry Saunders reformed The Warratahs. “I was keen but when Barry told me he didn’t want Wayne in the band, I declined the offer. I thought Barry and Wayne’s songs provided a good counterbalance. There were no hard feelings and although I have had a closer relationship with Wayne in subsequent years, I’ve also played on two of Barry’s solo albums.”

In 1996 Brown shifted to Dublin (wife Lynne, a longtime Radio New Zealand employee, scored a lucrative position in Irish radio). He soon established his credentials, regularly recording for Irish radio and television, and met and played with the cream of Dublin’s musicians, which included Noel Redding.

Noel Redding, the guitarist relegated to bass duties in the Jimi Hendrix Experience, relocated to the small Irish town of Clonakilty in the 1970s.

“Yes well that was an experience alright,” says Brown. “He was a grumpy bugger is what I remember most, felt ripped off by the whole Hendrix experience. I only did two gigs, his local pub in Clonakilty and a studio recording of ‘Rain’, the Beatles song.”

Returning to New Zealand in 1999, Brown’s marriage fell apart two years later. He spent a spell in Auckland but it’s Wellington where his roots are and Wellington where he now resides. At one stage Clinton Brown was juggling three bands, a permanent member of all. He still tours and records with Wayne Mason (he produced Mason’s album Same Boy), he has played in Irish bands Mickey Finn and the Shenanigans, and he played on and produced Warren Love’s 2007 album Cow Jazz.

In 2011 Clinton Brown formed Rag Poets, featuring vocalist Carl Evensen, guitarist Dave Murphy, keyboardist Alan Norman and drummer Vic Singe, old school heavyweights all. “We play covers but not predictable covers. We play roots music, country rock, R&B, all sorts. I’m playing music I love with people I love. Playing music is all I’ve ever known and as long as I enjoy it, which I am, I will keep on playing.”

--

The Rag Poets were still going strong when, on 24 February 2024, Clinton Brown died, following knee surgery. Over a lifetime of playing live and recording, Clinton made countless friends, was a much loved member of many bands, and a mentor to young musicians coming through.