In New Zealand, Clarke’s comic cow-cocky slowly took shape in Victoria University revues such as Extrav in 1969 and then the late-night Knickers, Knackers and Knockers shows which ran at Downstage Theatre for about 18 months. Also in the cast were Ginette McDonald, John Banas and Paul Holmes.

Roger Hall assembled a cast of Clarke, Dave Smith, Helene Wong and Cathy Downes for a similarly popular show titled One in Five. A performance in the Wellington Concert Chamber had been recorded and was repackaged as The Brian Edwards Show, at a time when the broadcaster was contesting the 1972 election for the Labour Party.

By this time, Clarke was on his OE in London but on the album can be heard performing an early prototype of Dagg. Then named Bruce, he phones his mate Trev to talk about the wild, boozy things he got up to the night before. Another sketch, written by Hall, was a television interview with a farmer who thought it was newsworthy finding all his sheep in a paddock dead. It turns out that the flock of deceased sheep was only two in number.

Clarke made another appearance on vinyl in 1973 with ‘The Royal Wedding Stakes’ b/w ‘My Husband and I’. It was a send-up of the dull-as-dish-water radio commentary of the wedding of Princess Anne to Captain Mark Phillips.

The first national appearance of Taihape’s Fred Dagg was on the television programme Gallery.

The first national appearance of Taihape’s Fred Dagg was on the television programme Gallery and there was no real science or even consideration behind his naming. Said Clarke, “David Exel was the reporter and we had to give the character a name. He thought Fred. I thought Dagg. So it was.”

Other television appearances followed on Gallery, Country Calendar, and Nationwide. In the second series of Buck House – New Zealand’s first sitcom – Clarke was cast as Ken. His catch phrase was “That’ll be the door”.

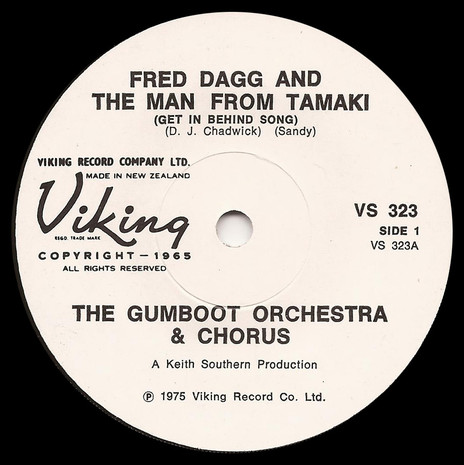

In 1975, to coincide with the general election which saw Robert Muldoon sweep to power, Viking Records released ‘Fred Dagg and the Man from Tamaki (Get in Behind Song)’ as performed by the Gumboot Orchestra and Chorus.

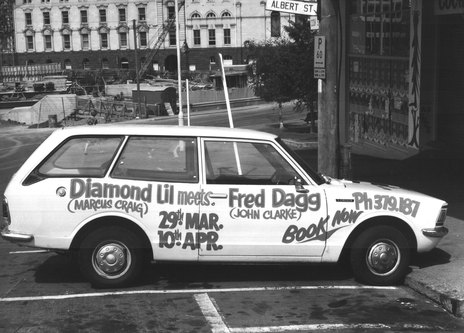

As Dagg’s popularity grew, Clarke enlisted friend John Barnett to manage him. Operating from a small office in Willis Street, Barnett – who later established South Pacific Pictures – organised more recordings, live appearances, advertisements, and broadcasting commitments. Merchandising such as books and T-shirts followed.

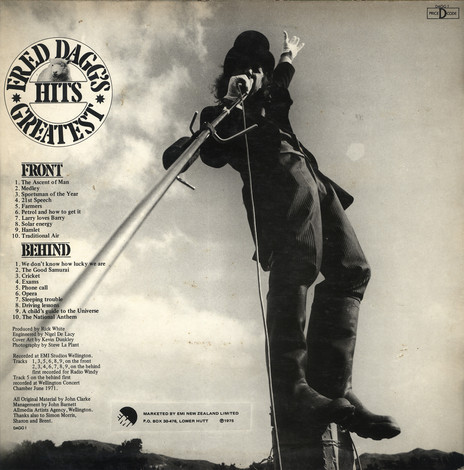

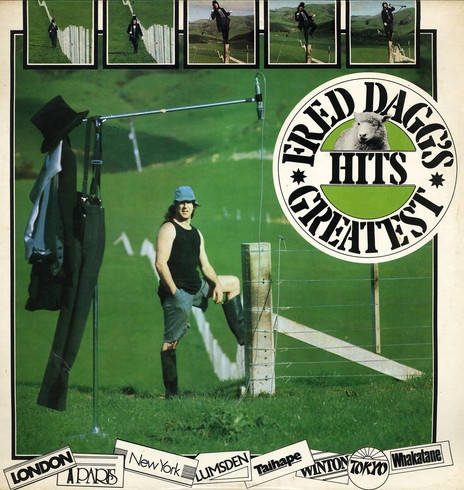

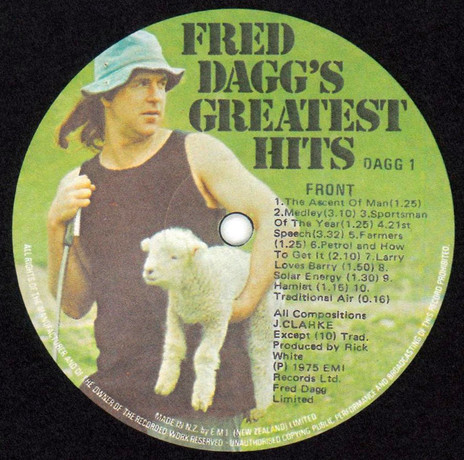

Dagg’s 1975 debut album Fred Dagg’s Greatest Hits (Dagg 1) had sides labelled Front and Behind. Costing only $8000 to record, it was a mixed bag of 20 tracks. Some were from short appearances on Lindsay Yeo’s 2ZB breakfast show that were reworked by producer Rick White (formerly guitarist with Farmyard and Tom Thumb). ‘Phone Call’ had appeared on the aforementioned One in Five; the five musical items included ‘We Don’t Know How Lucky We Are’, ‘The National Anthem’, ‘Larry Loves Barry’ (about a fellow who wants to marry his emu) and ‘Medley’.

According to Clarke, “I asked for some farmyard noises and ad-libbed a medley of various different things to fill out the time; there were some silly things [wife] Helen and I did at home (‘If You Were Acquainted With Susan’), some were ridiculous settings of famous but old songs (‘Moon River’), some were interpolations of the Dagg family into popular lyrics (‘Hey Jude’). Whenever a transition was difficult or I needed time to think, I shouted at the dog or one of the progeny.”

Clarke was credited on the album cover with “All Original Material”, a phrase of some ambiguity. When the album sold 80,000 copies in three weeks the representatives of those not given songwriting credits suddenly piped up. To placate the original copyright holders, EMI re-released the album (Dagg 2).

‘Medley’ was replaced by two new spoken pieces and the individual tracks boldly credited to “J. Clarke”. By then, though, the sales horse had well and truly bolted and today most copies of the album that appear in second-hand record shops or online sales websites are the original release.

With the benefit of hindsight, Barnett later thought, “We should have paid for the studio time ourselves and owned the whole thing, but we went and did a deal with EMI. I negotiated the contract so it had an ‘Escalator Clause’ which meant for every so many thousand that were sold the royalty went up. They never anticipated it would sell 120,000 copies so by the time we hit the upper levels we were actually on a higher royalty rate than The Beatles or The Rolling Stones.”

‘We Don’t Know How Lucky We Are’ b/w ‘Larry Loves Barry’ (produced by White) was also released and made it to No.17 in the charts. “In 1975,” said Clarke, “my record company presented me with a special award for [album] sales equivalent to 15 million in the US, which meant if I had been in the US, I would have made $15 million in royalties from this one record alone. But I don’t live in the US. The comparison is meaningless.”

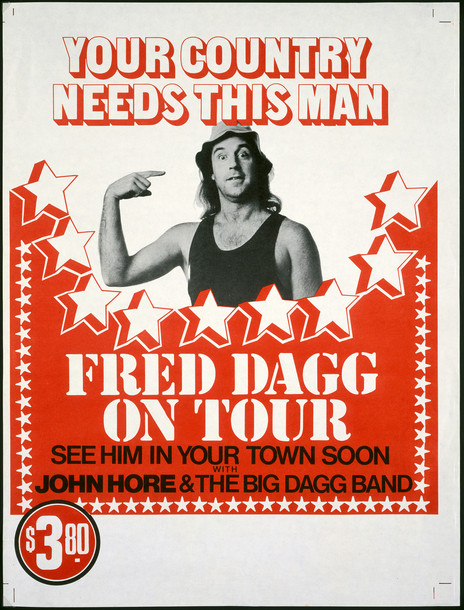

In 1976 there was a long nationwide winter tour for Dagg. The tour was promoted by Radio Hauraki DJ Ian Magan who had set up Concert Promotions Company (which later became Pacific Entertainment). According to Magan, it was one of the last “nook and cranny” tours. The itinerary was partly formulated from fan letters, with Clarke particularly wanting to please the kids around the country who hoped to see or even meet Fred Dagg in the flesh. The venues were less than salubrious, but according to Magan, “It didn’t worry us too much because we were new at the game and everyone was having a great time.”

At the end of each show performers and promoter would muck in to see how quickly the gear could be packed into the bus so that they could get to a pub for a bit of booze. On the first night the pack-down took 90 minutes. By the 10th show it was taking only 13 minutes. Says Magan, “John was very egalitarian and he’d never have anyone doing anything he wouldn’t do.”

The most expensive ticket for the national tour had been $5 and at the end of the tour the total audience number was estimated at 250,000. Clarke recalled, “The people were great and the tour – as distinct from my wandering on stage and doing the same thing every night – was great fun.”

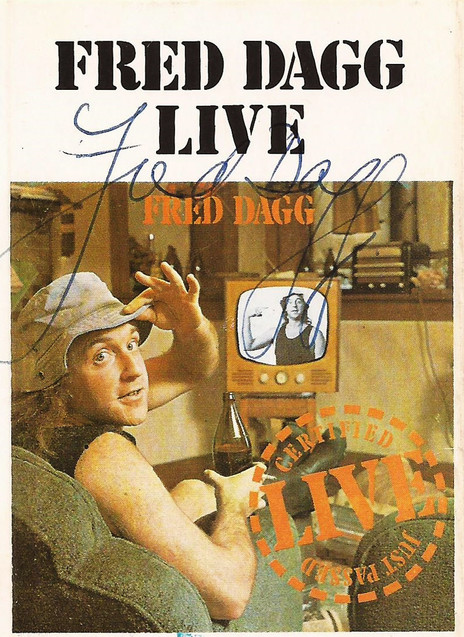

The 1976 album Fred Dagg Live (Dagg 3) was recorded at the Christchurch Town Hall during that tour. The 13 tracks are Dagg songs, monologues and musical interludes from The Big Dagg Band whose members were John Rangi, Bernadette and Pat Pukeroa, Mike Taewa, Jimmy Lake and special yodelling guest, John Hore.

Magan remembered that, “The Māori guys in the crew had a big pot of soup which was always full. They’d stop on the side of the road to get some puha or we’d shout them a few pork bones … In Nelson, John and I almost got caught because hotels had those smorgasbord lunches. John and I would go in and fill our plates for about $15 a head and then pass the food out the window to the Māori boys.”

Magan’s appraisal of the show was that he wouldn’t describe it “as a great comedy act. It was a series of accidents that worked well and the best thing was that it showed John in person to his audience. It gave him that contact outside of the television camera.”

Upon release in 1976, the single ‘Gumboots’ became an instant anthem.

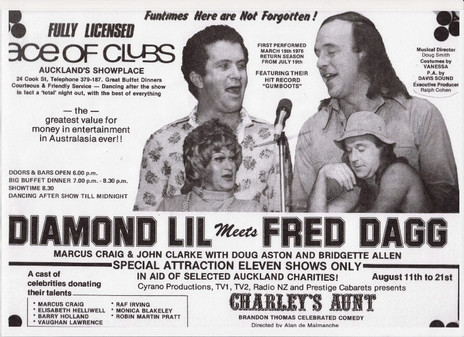

Upon release in 1976, the single ‘Gumboots’ became an instant anthem. It quickly made its way up the local singles chart, reaching No.6 at its peak. With ‘Save the Last Dance For Me’ on the B-side, ‘Gumboots’ stayed in the charts for three months.

The following year, ‘Fred Dagg’s Big Single’ contained six tracks taken from the 37-minute short-film Dagg Day Afternoon which accompanied Geoff Murphy’s Wild Man feature. In the film Dagg and his seven siblings – all called Trevor – set out to find a six million dollar bionic ram (spoofing the then hugely popular television series The Six Million Dollar Man.) A mix of spoken-word satire and music, it includes the ‘Gumboots March’ played by the Lower Hutt Civic Band.

It is amazing to reflect on how deeply ingrained Fred Dagg became in New Zealand popular culture in such a short space of time, and that he has remained there. The relevance of many comedy creations lessens with the passing of time. Those that endure are the result of a special alchemy, in which the creator combines caricature, comic writing and performance with aspects of a widely accepted national identity. Fred Dagg (his hilarity largely undimmed 40 years later) is one such creation, best illustrated perhaps by the fact one of his black singlets is in Te Papa.

As for his creator, you could say he’s gone on to do quite well for himself across the Tasman. In the words of John Barnett, “It had been a terrific couple of years because we were great friends, and it all worked the way it was only supposed to in text books.”

One of the last musical projects involving Clarke was The Underwatermelon Man, a musical by Fane Flaws aimed at children of all ages. When Flaws told Clarke of the New Zealand musicians involved, among them the Finns, Che Fu, Jenny Morris, the Topp Twins and many others – he responded, “Yeah, I like it. But you’ll have to come to Melbourne. I don’t do aeroplanes.” There was no talk of remuneration, says Flaws.

The recording was done in the Melbourne home of Michael Den Elzen, who had been a member of Schnell Fenster. Flaws needed someone with an ADAT recorder, and Den Elzen offered his. Clarke did the vocal track on ‘The Hide & Seeky Bird’.

“It was a bizarre experience,” says Flaws. “The ADAT was in the living room, but the mic was in the bedroom. He was a total gentleman, he turned up at this flat in Melbourne, and sussed out the scene. It was primitive: he was amused by it, a number eight wire version of recording, not in a poufy studio with glass booths.

“So that’s where John did his performance, with me videoing him. I’d done a demo of the song in an English accent, like a toff. And when he said, well how do you want it, I said, however you want – thinking Fred Dagg. He did a brilliant thing. He talks a while then the backing singers come in and said ‘Righto boys, I’ll wait till these people stop singing’ … and just as they finished, he came in with the last line. Two takes. He didn’t need directing, that’s when you know you’ve got a great talent. I felt really privileged to have had that experience in the room with a comic genius.”

Clarke was always gracious to deal with, and generous to other performers. He kept an eye on what was emerging from New Zealand, music included, as reflected in his 1995 skit impersonating a rugby union official announcing the latest All Black team. It was full of New Zealand heroes, none of them rugby players. Among them were: “Locks: B. T Finn, N. M. Finn, King Country; wing three-quarters: D. Dobbyn, Auckland; centre: K. Te Kanawa, Auckland.”

Arthur Baysting, whose Neville Purvis alter ego was described as an “urban Fred Dagg”, was impressed by how popular – and loved – Clarke was in Australia, as well. “Without singlet or gumboots and without even changing his voice or looks, week after week on the ABC he mocked the politicians and powerbrokers. He was the smiling assassin, easily assuming their identities and giving them back their own words with a twinkle in his eye. Losing John Clarke and Murray Ball so close together isn’t funny.”

--

Matt Elliott is the author of 11 books including Kiwi Jokers: the rise and rise of New Zealand comedy (HarperCollins, Auckland, 1997)