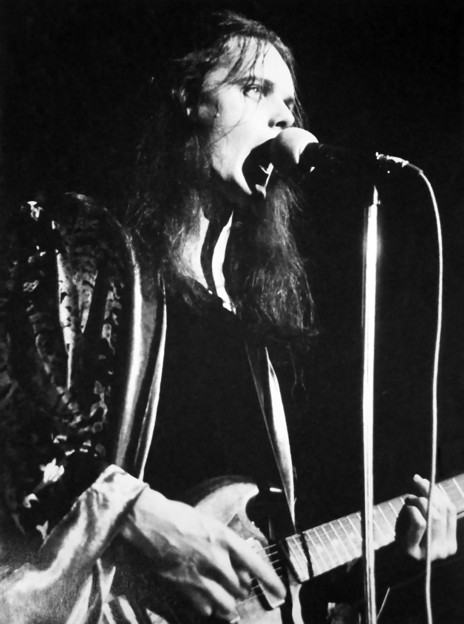

To say that Space Waltz stood out among the tuxedoed crooners and singing family groups that dominated the light entertainment show is an understatement.

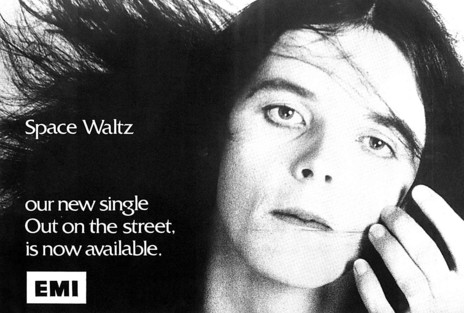

While Riddell’s appearance caused some visible discomfort among the all-male judging panel – “this effeminate thing is very commercial in the heavy area” blathered 2ZB deejay Paddy O’Donnell, while popular entertainer Howard Morrison batted his eyelids and blew mock kisses – there was evidently a hunger for it. Released as a single only days later, ‘Out On The Street’ became the first local No.1 in four years.

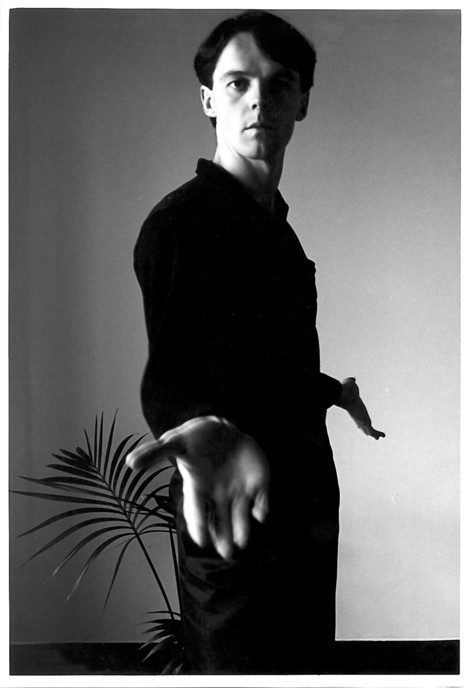

Alastair Riddell had seized his moment and will forever be characterised as New Zealand’s glam-rock icon.

Alastair Riddell had seized his moment and will forever be characterised as New Zealand’s glam-rock icon; our homegrown Bowie. When Bowie died in 2016, Riddell was one of the first commentators the media went to for a soundbite. He later performed moving tributes to Bowie, performing a stirring ‘All The Madmen’ on RNZ National’s Music 101, and touring as part of the Waiting In The Sky tribute show.

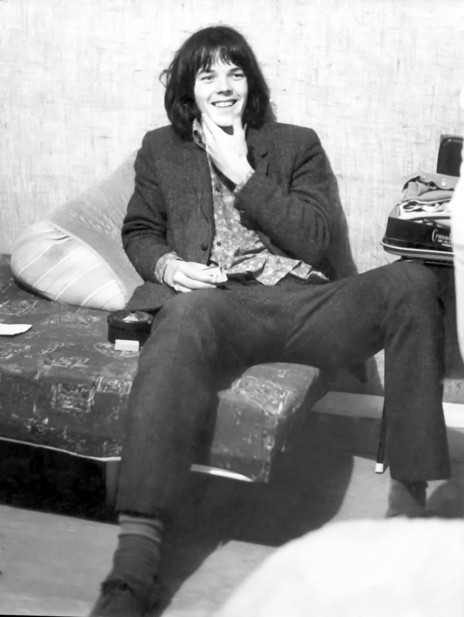

But Riddell was always more than just a Bowie clone. Growing up in the 1950s and 60s in the Waitakere suburb of Titirangi, his artistic sensibilities were encouraged from a young age. Titirangi at that time was a bohemian stronghold populated by actors, potters and painters, a community in which the Riddell family felt at home. Alastair’s mother had studied art at Elam; his father, a publisher, sang Irish and Scottish folk songs and had a strong interest in politics.

“My parents were politically liberal and they were on a kind of bohemian fringe. They were probably not as radical as some, but there was a strong message that came through: be yourself, think for yourself. My mum always said, ‘don’t be a conformist. People who do things are not conformists’, and my dad would have agreed completely.”

Though he studied classical piano, his first musical passion was the blues. In the early 60s, before the music had been popularised by the likes of The Rolling Stones and John Mayall, the young Riddell latched onto the folk blues of Lead Belly and Josh White. His parents encouraged his interest in this black American music, as it chimed with their support of the civil rights movement.

In those pre-Beatle days, pop was motley fare. Elvis, he recalls, “had gone to Blue Hawaii. I went to one Elvis movie and never wanted to see another one.” But he remembers going with his elder brother Ron to a five-act bill at the Auckland Town Hall, where local rocker Johnny Devlin stood out amongst middle-of-the-road entertainers like Toni Williams and Howard Morrison. “I liked the leather and the attitude. It was raw and exciting.”

The Shadows inspired Alastair, at age 12, to get his first electric guitar: a Jansen Invader (“Lake Placid blue”) with a vibrato arm.

Early influences were the Shadows, the Beatles, and the Who. Then Riddell began seeing New Zealand bands at the Galaxie.

Then The Beatles happened. His father bought Alastair and Ron tickets to see them at the Town Hall. Alastair was inspired by The Beatles’ creativity, and that of the British bands that followed in their wake: The Who, Kinks, Small Faces.

At the Galaxie in Lower Queen Street, he would catch local groups The La De Da’s, The Underdogs and The Action on Friday nights. He and Ron formed their own band, Peale, and played at the school balls.

His interest in blues persisted, though he was no purist. He heard creative extensions of the blues in the music of Cream and Jimi Hendrix: both inspirations for his next group, The Original Sun Blues Band. With friend Selwyn Jones, he organised the First National Blues Convention at Moller’s Farm in West Auckland in December 1968, a one-day event featuring various Auckland blues outfits including the Original Sun. A second convention the following year built on the success of the first, spanning a full weekend and attracting performers and crowds from all over the country. The 1969 event included early appearances by both Rick Bryant (with the Wellington blues band Gutbucket) and Graham Brazier (fronting Auckland jug band The Greasy Handful.)

The blues boom coincided with the rise of the counter-culture and the protest movement. By the time he was at university, Riddell was attending demonstrations against South African apartheid and the Vietnam War. But he was beginning to question whether the blues was the best vehicle for his musical ideas.

An alternative presented itself in some of the new sounds coming out of Britain, particularly the “progressive” rock of groups like King Crimson, Yes and Van Der Graaf Generator. In 1972 he formed Orb, with guitarist Wally Wilkinson, drummer Paul Crowther, keyboardist Tony (later Eddie) Rayner and bass player Peter Cuddihy. Their repertoire combined prog covers with early Riddell originals.

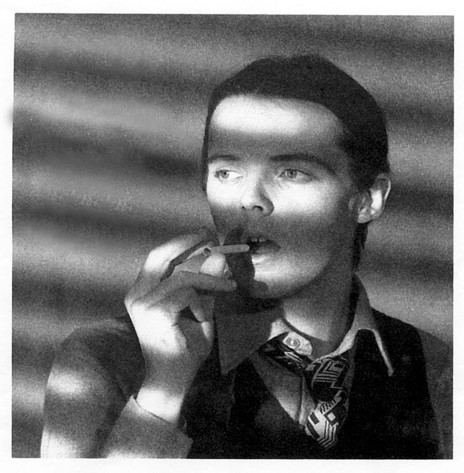

As prog became more bombastic and self-absorbed, Alastair found himself leaning more to the theatricalised pop of David Bowie and Roxy Music, and the glam rock and roll of T. Rex. He was especially drawn by Bowie’s philosophically-inclined songs on albums like The Man Who Sold The World and Hunky Dory. He also enjoyed the dressing up.

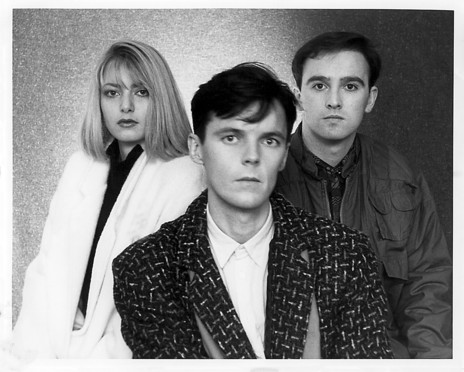

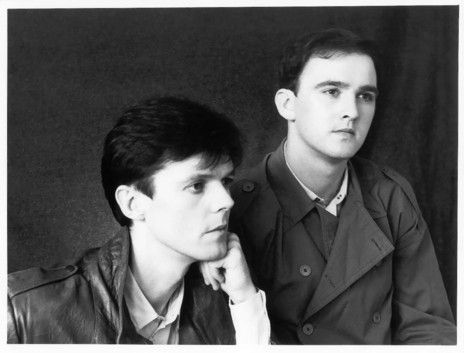

Orb split up after eighteen months, with Crowther, Wilkinson and Rayner joining the burgeoning Split Ends, though Rayner would join soon Riddell again (along with drummer Brent Eccles and guitarist Greg Clark) in Space Waltz. In the interim, Riddell formed Stuart and the Belmonts, a weddings-and-pubs covers band, satirically named after Brian Stuart, head of the Auckland vice squad, and the Holden Belmont cars driven by the New Zealand Police.

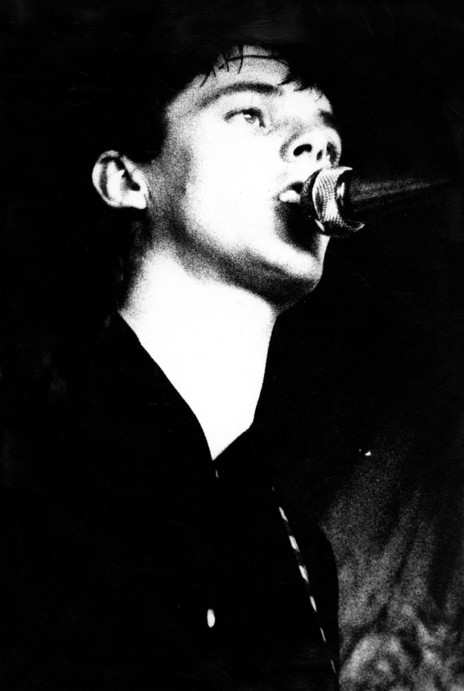

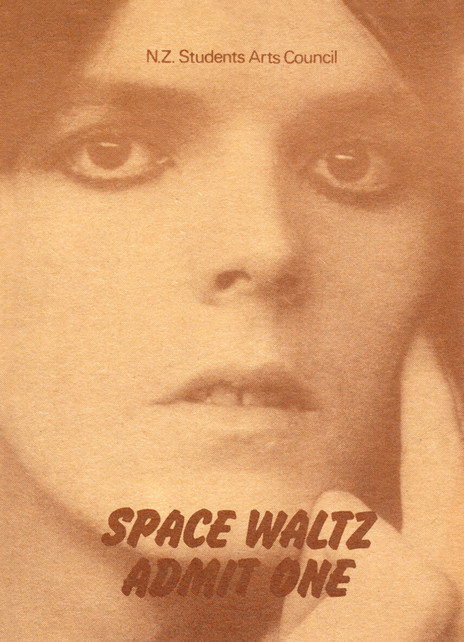

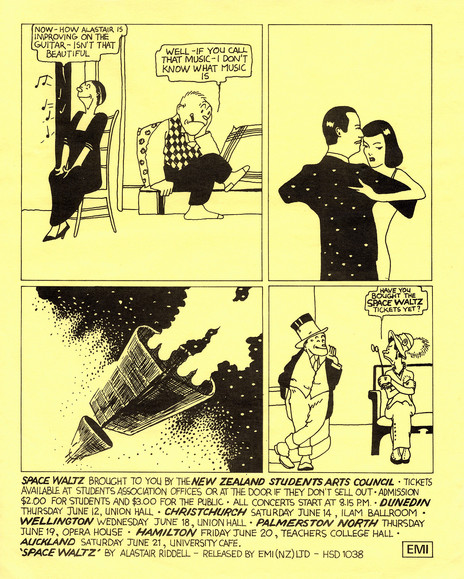

In 1973 Split Ends catapulted themselves into the nation’s consciousness with an appearance on New Faces. At a time when television viewers had only one channel to watch, the Ends had a virtually captive audience. The following year, Space Waltz pulled the same trick.

“We actually ambushed them,” Riddell recalls. “‘Out On The Street’ wasn’t even the song we did for the audition. But then we went down to Wellington and said ‘this is the song we think we should do’ and [producer] Chris Bourne said all right. So we went up to Broadcasting House and recorded it, then went down to the television studio and performed it, literally all in the space of a few hours.”

‘Out On The Street’ was soon a national hit and Riddell a fully-fledged pop star.

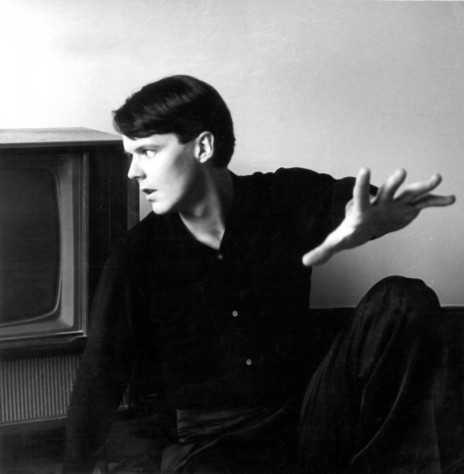

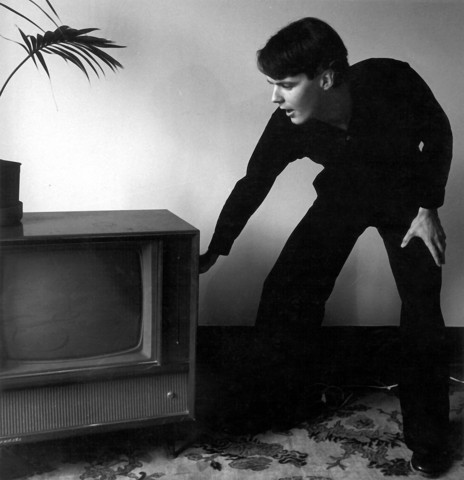

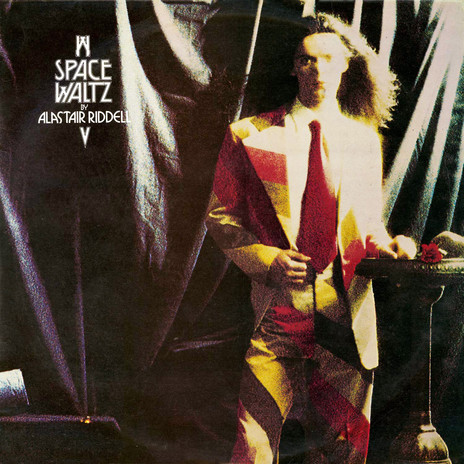

Released by EMI, ‘Out On The Street’ was soon a national hit and Riddell a fully-fledged pop star. Space Waltz toured the country. “He pranced about in an olive, canary and pink candy-stripe suit,” noted the Christchurch Press. “For the second half he sauntered and leapt about the stage in black, plum and gold velvet. He cast disdainful eyes at his delighted audience, then raised a hand to his forehead in mock shame.”

In Auckland they packed out the Town Hall, where Alastair had watched The Beatles a decade before. A follow-up single, ‘Fraulein Love’, was released.

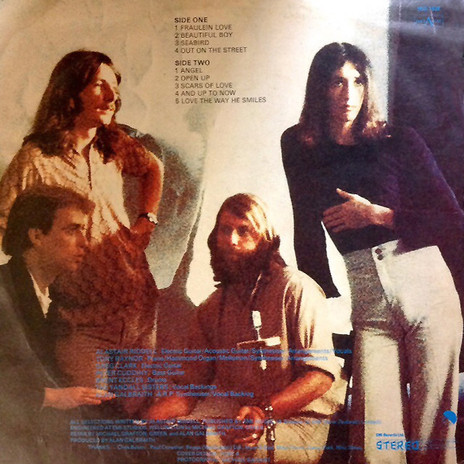

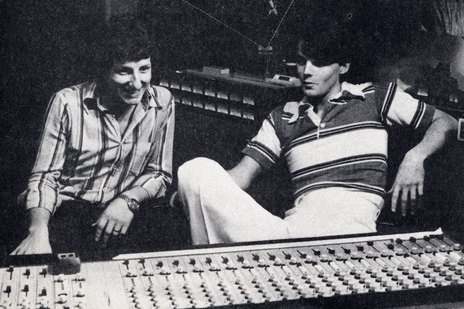

But what might have been a sustained career faltered. By the time the album Space Waltz by Alastair Riddell came out in late 1975, Rayner had left for the now renamed Split Enz and the glam moment had almost passed. Relocating to Australia, the remaining members found themselves divided over what to do next. Australian entrepreneur Michael Browning had just signed AC/DC, was about to take them to Britain, and offered to take Space Waltz as well, but Riddell’s bandmates demurred.

Back in New Zealand, EMI offered little guidance, seemingly at a loss as to how to develop or market their star. Riddell recalls a suggestion from one of the company honchos that he try writing something in the style of Bachman Turner Overdrive. “That’s not who I am at all,” he says, looking back. “My energy just completely dissipated.”

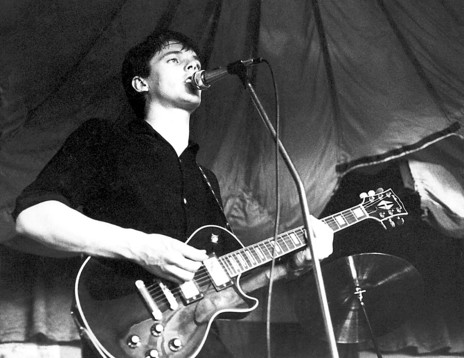

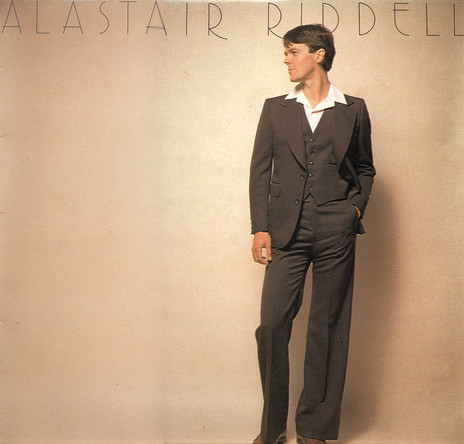

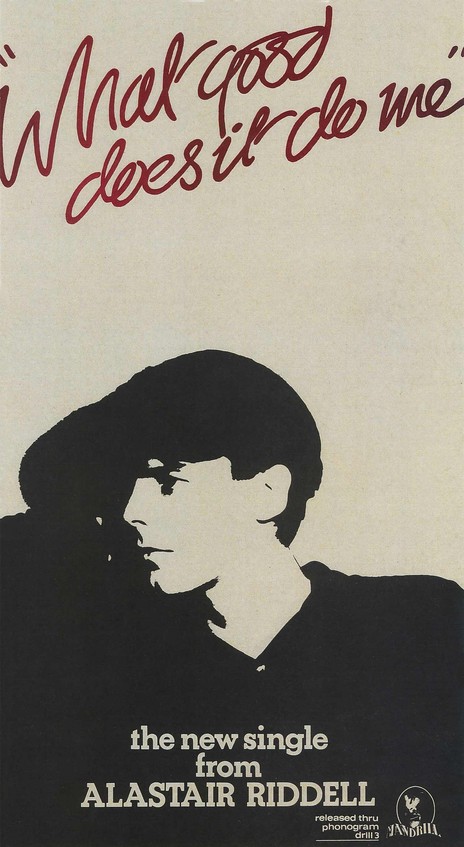

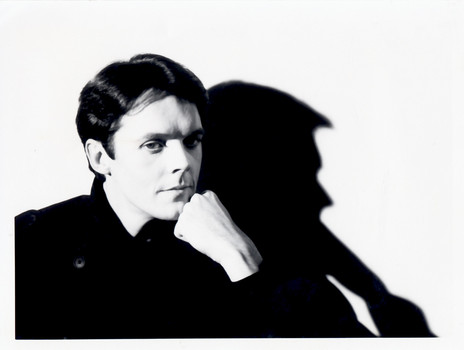

In 1977 he turned down an offer to join Split Enz, by this time based in London. Though tempted, he had been writing new material and reasoned he would find more creative satisfaction if he continued to front his own show. That year he released his first solo single, ‘Wonder Ones’, re-emerging minus the satin and eye-shadow, his hair cut fashionably short, clothes tailored more in the manner of Bowie’s Thin White Duke. ‘Wonder Ones’ was “a remarkable little piece,” wrote Francis Stark in Rip It Up. “It takes its place alongside ‘Gutter Black’ as single of the year so far.”

He hit the road around New Zealand again, released a couple more singles and an album simply titled Alastair Riddell. Though he and his new band, dubbed The Wonder Ones, played some major shows – including a one-day festival with Dragon at Moller’s Farm, scene of the old Blues Conventions – he couldn’t gain the commercial traction needed to sustain his band.

As the end of the decade approached Riddell headed overseas once more. He formed another band and began recording an album in the United States, but this group – optimistically titled Radiomusic – broke up before the project was complete. After a spell in Britain, he returned to New Zealand where in 1982 he released his third album, Positive Action and formed another group, Modern Contours. Yet once again he found himself out of step with the times. In the era of post-punk and the raw Dunedin sound, his new, heavily synthesiser-based sound was met largely with indifference.

Once again, he set off for England where he formed yet another band, Flying Colours, and again almost completed an album. He finally returned to New Zealand in 1989, after his father had a stroke. Even then, he continued writing songs, but – now married with four young children to support – a full-time musical career was untenable. Instead he pursued various non-musical enterprises – running a clothes shop, growing and selling flowers – and played part-time in a Celtic band.

In 2005 he performed a so-called “comeback concert” in Titirangi. It was meant to be the official launch of Trick Of The Light, his first album in 22 years, but the release was delayed. In 2012 a single ‘Last Of The Golden Weather’ emerged, promoted as “the first track from his forthcoming album.” The sound was both familiar and fresh; like a distant son of David Bowie singing on a South Pacific shore. As yet the album has not been released.

Riddell has remained creatively active, pouring much of his artistic energy into filmmaking.

Riddell has remained creatively active, pouring much of his artistic energy into filmmaking. 2014 saw the release of Broken Hallelujah, a feature film directed and scored by Riddell, written, produced by and starring his wife Vanessa.

His older music too has found new life in the movies. In 2014, ‘Angel’ – a glam anthem from the Space Waltz album – played over the credits of the popular horror-comedy film Housebound, while ‘Fraulein Love’ can be heard in Taika Waititi’s 2016 hit Hunt For The Wilderpeople.

Riddell remains passionate about music, and philosophical about the vagaries of a musical career. In 2005, he told Auckland writer Peter Malcouronne: “Some people believe … you make your own fortune, that somehow if you’re not successful, that you’ve done something wrong … I don’t really go for that kind of thinking. That idea the universe has some sort of mechanical process whereby if you put your foot in the right place, God will reward you — that’s tosh. Shit happens, basically.”

Yet through the ups and downs he has always made music, always remained true to the credo he adopted at a young age: don’t be a conformist. That’s a success.