HMV artists in 1969, including The Avengers, Des Britten, Top Shelf, The Simple Image, Quincy Conserve, Yolande Gibson, Steve Allen, Allison Durbin, Brendan Dugan, with producer Peter Dawkins

'"The Greatest Recording Organisation In The World"

The Wellington based HMV (later EMI) recording studios and record pressing plants were central to the New Zealand recording industry for several decades, finally shutting up shop in 1987. The pressing plant opened in 1948 in Kilbirnie then moved to Lower Hutt in 1954.

Peter McLennan tracks the paths these facilities took, bringing together earlier articles on the operations and what became of them, including an interview by Nick Bollinger with studio head Frank Douglas, a reflection on the end of the pressing plant from Chris Bourke, Peter at last addresses an urban legend that has gone around for some years, and finally, via Chris Bourke again, the tale of Bruno Lawrence's ban from HMV, as told by Shane Hales. Peter explains:

During the 1960s “there were very few recording studios operating in the country and the majority of homegrown hits came out of the HMV Studios in Wellington," Frank Douglas told Nick Bollinger (Music in New Zealand, Autumn 1992). His Master’s Voice (NZ) Ltd., a subsidiary of the English EMI multinational, had owned the studio since 1962. In 1972 both the company and the studio changed their name locally to EMI to reflect global EMI policy.

Many important local artists recorded there, including The Avengers, Maria Dallas, John Hore, Dinah Lee, Mark Williams, Creation, BLERTA, Allison Durbin, The Simple Image, Jay Epae, The Fourmyula, Quincy Conserve, Rockinghorse, Hogsnort Rupert, Shane, Nash Chase, The Kal-Q-Lated Risk, and Fred Dagg.

The studio eventually closed its doors in 1987, with EMI shutting their pressing plant and studio facilities and relocating the head office to Auckland. They shipped their vinyl pressing and cassette duplicating equipment to Australia. EMI did NOT dump this equipment in Wellington Harbour, as urban legend may have it.

Although HMV had been recording in the Wakefield Street facilities for some years (originally in the cafeteria!), in 1964 it purchased the adjacent Lotus Studios off Fred Green, who had owned it for two years after buying it from Tasman Vaccine Laboratories. Recording engineers Terry Patterson and Frank Douglas were the studio's founders in 1960 and they came over with the studio to HMV/EMI.

The Avengers outside the HMV building in Wakefield Street, Wellington

The British EMI concern went back to 1898 (as The Gramophone Company Limited) but by the middle of the 20th Century there were branches throughout the world. Trading as His Master's Voice (NZ) Ltd, the New Zealand entity had first been established as Gramophonium by EJ Hyams in Wellington in 1913.

Gramophonium was absorbed by EMI in 1926 and began recording the next year in Rotorua. HMV, as it was commonly known, commenced pressing locally in 1948 in NZ and recorded the regular New Zealand artist releases in a variety of locations throughout the 1950s.

In the early 1960s the company was keen to expand what they called "Local Productions" and also to take in custom recording work for smaller independent labels including Joe Brown (distributed by HMV). In time the studio would become the primary source of local recordings in Wellington, including backing tracks for some NZBC television shows.

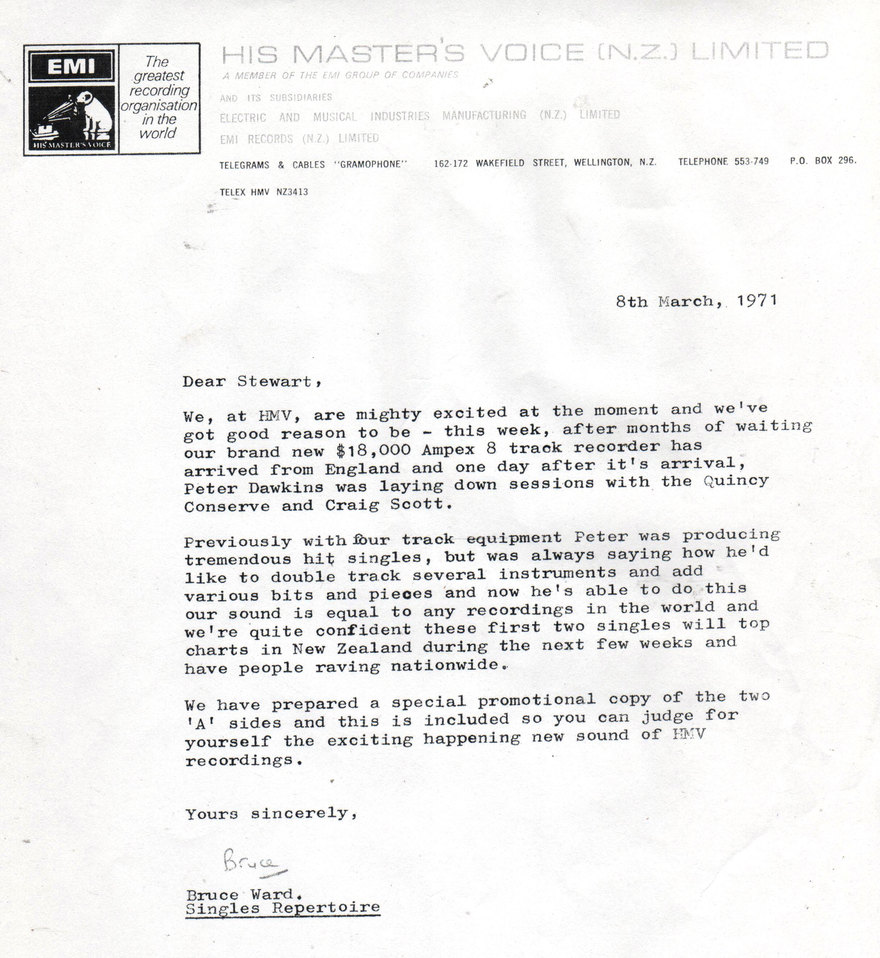

In 1966 EMI got their first Ampex stereo machines, transforming their recording technique by allowing the studio and producers to "bounce" down tracks and add overdubs. The recordings grew increasingly complex.

An 8-track machine was added in 1971.

HMV studios get their 8 Track machine in 1971 - Grant Gillanders collection

From 1962 through to the mid-1970s a number of in-house producers were hired by HMV, including Howard Gable, Nick Karavias, Peter Dawkins and Alan Galbraith. They also fulfilled an A&R role, signing acts and sourcing material. Peter Dawkins would go on to become one of the most successful producers in Australasia in the 1980s (Dragon, Mi-Sex). Musical directors and arrangers HMV used included Don Richardson, Garth Young and Brian Hands.

Frank Douglas recalls that “The EMI Studio was based in central Wellington, in Wakefield St. In 1976 EMI shifted their studios to Lower Hutt, as they owned land out there. They lost 80 per cent of their clients after the shift. EMI at the Hutt became basically a manufacturing unit.”

They had three studios at their Hutt location – one for voiceover, one for commercials, and a 16-track studio, which Frank Douglas described as the best in the country. EMI studios worldwide were all equipped with Neve desks as a standard; the one used by EMI was still active in Auckland at York Street Recording Studio until May, 2014.

Producer Peter Dawkins at HMV, early 1970s

EMl Factory Closes

Pressing Problem for NZ Music

Chris Bourke, Rip It Up, August 1987.

New Zealand's only record pressing plant, EMI in Lower Hutt, is to close at the end of September – a move that has major implications, particularly for this country's independent record labels.

The decisions which EMI attributes to the rise in CD and cassette sales, means that all vinyl records sold here will have to be imported. Several of the major labels, whose parent companies have pressing plants overseas, already import many or all of their albums. But for the indies, who will have to send their tapes overseas to be pressed, the closure means greatly increased costs in administration and freight, which could result in higher record prices and fewer local albums being released.

"I think it's wrong in a country the size of New Zealand that we can't sustain some type of pressing plant," says Tim Murdoch, head of WEA and president of the Recording Industry Association. "If the pressings are going to be sourced out of Australia, you're at the whim of the Australian companies, and obviously there will be less records released, as New Zealand companies will have to be more selective than they were in the past."

With several companies already importing their general release records the prices shouldn't immediately be affected, but the inconvenience of ordering stock from Australia will be tested during the peak selling months leading to Christmas.

"The acid test will be to see how long things are held up by Customs for clearance," says Brian Pitts of Virgin Records.

HMV presses, 1957. Photo by Morrie Hill

The plant closure is a nuisance, says Jim Moss of Jayrem. "It's going to make it very difficult for our sort of business which tends to be in smaller runs. We're going to have to take more risks. How many do you get pressed? What if something takes off, how long are you out of stock? We'll just have to adapt, I guess."

Distribution through the major companies is one way for the independent labels to keep in operation, says Tim Murdoch. "We're looking after Warrior and Maui Records and they won't notice any difference. They'll still bring their tapes to us and we'll take the records, just the same."

"What worries me," says Jim Moss, "is all these little labels – the Skank Records, Meltdown, Rational, the list goes on – what are they going to do? They're a valuable part of the industry. If Skank Records want to do their own thing how are they going to do it? I don't think they should told 'Oh you've got to go along to Jim Moss and let him organise it for you', and I'm the big brother who distributes the records. It could worry me if those small labels all ended up being cassette labels, because a lot of people like records."

"It's as though the whole thing has been brought upon us and internationally the decision's been made, for lovers of black plastic, tough is the message. It's almost impossible to sell records to some retail chains now – all they're interested in is compact discs and cassettes."

With capital tied up in CDs, stores are stocking less vinyl records. But vinyl isn't dead – there will always be acts that sell better on vinyl than other forms, just as some acts (reggae, for example) sell mostly on cassette. Also, although the death knell for the 7-inch single has been sounded for some time, that is the most convenient medium for radio to use.

"Are radio going to accept cartridges – what's going to happen?" says Moss. "If radio are going to support New Zealand music. and the vinyl manufacturing is being taken away from us, we're going to have to get together and work out some alternative for getting music on radio." While the increase in CD and cassette sales is one reason for the decline in vinyl production here, some companies have been importing all their records recently.

EMI, Lower Hutt in 1976 - Chris Bourke Collection

Tim Murdoch: "There are two sides to the coin. CBS and PolyGram, two of the biggest companies, took their pressings away from EMI because they could get them cheaper in Australia. That's probably accelerated this situation. I can understand CBS because they own their factory in Australia, whereas PolyGram don't have a factory there. So they are now in a reliant situation." [Bruce Ward notes: no PolyGram or CBS records were ever pressed at EMI as PolyGram had their own plant, Green & Hall, later PolyGram Record Services, in Kilbirnie. However, industry veteran Jonathan Hughes disputes this, saying "PolyGram got records pressed in Australia and at EMI. There was one time when the van driving the records up from Lower Hutt overturned on the Desert Road ... what a mess. Thankfully no one was hurt , but it killed some releases / stock and it did further cement the drift across the Tasman for production. " Hughes was the production controller for PolyGram in the shift from PolyG ram to EMI. ]

"I was always very conscious of that – that we didn't have a factory to call on in Australia, and that EMI had looked after us for a number of years, so we should support them. I think that had the New Zealand industry been a little more long-sighted and supportive, 'support your local sheriff', this wouldn't have come about. But then you'll get the argument that the service from EMI was second-rate, and at times I'd have to agree with them." One music company source said it could sometimes be quicker to order pressings from Australia than locally.

Is there any chance that another pressing plant will be started? Modern pressing equipment would be available from American companies that have closed – because of the decline in vinyl production.

Brian Pitts: "The fall in the manufacturing figures for LPs is so dramatic, there's no reason to suppose that the same rate of fall isn't going to continue." Tim Murdoch thinks it's unlikely that a cooperative pressing plant will happen – the RIANZ's constitution prevents it from setting one up – but Jim Moss says, "There are already some noises being made. I've had a couple of calls from people who are reasonably financial, who are interest in putting a group together."

"We're just going to have to adapt. If it looks as if there isn't going to be a New Zealand plant, if the effort of the people looking at buying a plant don't come off, I'll just have to visit Australia and get organised."

[Courtesy of Chris Bourke]

Frank Douglas, 1965 - Chris Bourke Collection

The Golden Years of HMV: An interview with Frank Douglas

By Nick Bollinger, originally published in Music in NZ, Autumn 1992.

Looking back the sixties seem like a golden age in New Zealand recording. There were a number of local record labels releasing a steady stream of singles, plus the occasional album. These received generous radio and television exposure, sold in impressive numbers and had a high profile on the pop charts. During this period there were very few recording studios operating in the country and the majority of homegrown hits came out of the HMV Studios in Wellington.

Frank Douglas worked at the studio as a recording engineer from its inception to the day it closed in 1987. In conversation Douglas always stresses the team spirit that made the studio tick. But his former colleagues are quick to credit him with a vital role in its success. As one of them said, "Frank was HMV." Frank Douglas is now a freelance engineer based in Wellington. The following conversation with Nick Bollinger was conducted at Douglas's home in December 1991.

Nick Bollinger: How did you become a recording engineer?

Frank Douglas: I started off as a radio serviceman apprentice and served my five year apprenticeship and came out registered. I spent one year servicing at Columbus Radio Centre in Wellington, and Columbus had a studio called Tanza which they needed an engineer for. I was offered the position and transferred there.

I more or less learned my craft from a fellow named Terry Patterson, who was the manager at that stage. We had a record label (Tanza) that had been going since the late forties. It was all 78s in those days. There wasn't much local recording going on in Wellington at that stage. 80 per cent of our work was radio commercials, which were directly cut on to acetate discs which the radio stations used to play.

It's 1966 and Carol Cunningham of Auckland has the first pressing of Haere-mai which was produced as part of a tourist promotion campaign called "Haere-mai Year". Looking on is Mr D Grylls, the HMV factory foreman - National Library of New Zealand

NB: In those days what did recording engineering involve?

FD: It was simple. It was all valve. Basically all you had was a microphone channel. We had 8, and you connected 8 microphones to these. You had bass and treble controls and you had to mix each channel while you recorded. You either had to get it right the first time or do it again, so it was pretty hard really, compared to nowadays. You just recorded everything at once and hoped to heaven it turned out right. You had to trust your ears.

There were usually one or two people who had a say in the balance, but once we got the balance right we just went and recorded straight through. If there was a mistake then we had to go over it again; sometimes you did the same thing maybe 50 times.

NB: Was this on to magnetic tape?

FD: It was magnetic tape in 59. Before that you would do it straight on to disc.

NB: How did you come to work for EMl?

FD: I left Tanza in 1960 and Terry Patterson and I started another studio, called Lotus Studios, which was owned by Tasman Vaccine Laboratories. Lotus lasted two years then Fred Green bought the studios off TVL, and in 1964 EMI bought the studios off Fred Green. EMI originated in Britain but had branches throughout the world – there were probably up to 50 or 60 EMI outlets worldwide.

At a Simple Image session, band manager Tom McDonald, bassist Cass Gascoigne and HMV's Howard Gable listen to a playback - Photo by Barry Clothier. Grant Gillanders Collection

NB: What spurred them to take over a studio in Wellington?

FD: Basically to see if there was a profit in local productions, which there was.

NB: Did you find you needed to develop new techniques to record the pop groups and singers?

FD: I used to do a lot of disc cutting as well so of course you would hear everything that came from overseas. You'd hear certain things and think, 'Now how have they done that?' and try to work it out and maybe try and use it on a session, see how it worked.

We developed our own little techniques of echo and repeated echo and those things that were popular back then. In the early days we didn't have what was called an echo plate which was probably worth about seven or eight thousand dollars, which in those days was a hell of a lot of money. So we made our own, which probably cost us about $100 and worked very well.

NB: Who designed and built it?

FD: There was a chap named Brian McIllwaine who worked with me in those days, and he and I built it together. It consisted of a huge steel pipe bent around a frame, and a sheet of steel anchored to it, with a loudspeaker driving this sheet of steel with a crystal pickup on top to pick up vibrations – and it really worked well. We used it on a lot of stuff. The early Maria Dallas recordings. From early 64 to probably 68, it was used.

Frank Douglas in 1976 - Chris Bourke Collection

NB: Once EMI entered the picture did the nature of your work change much?

FD: Yes, with Lotus we were basically doing radio commercials and radio programme production. When EMI bought into it there was a chap called Alec Mowat who was more or less in charge of local repertoire. He was really keen on local artists and basically if anyone came in who he thought might have a reasonable chance, we went ahead and did an audition tape. If it turned out right we went ahead and made a recording. Usually it was a 7-inch single, double-sided, and if the single took off we did an LP.

NB: And EMI provided the budget?

FD: Yes, EMI had a budget for these things. "Local productions" they called it. We were probably doing 80 per cent of the local production at that stage. They all recorded at EMI, but not necessarily for EMI's HMV label. John Hore recorded for the Joe Brown label, Maria Dallas and Dinah Lee for Viking. There were all these different labels.

We also started doing work for television when it started. Pete Sinclair did a programme once a week (Let's Go) and we used to record all the backings three days before it was due to air. They would go out live, with the backings performed. We used to record 8 or 10 backings a week but that was only a day to a day-and-a-half's work.

HMV's Frank Douglas at the desk with The Avengers on 5 December 1967 on the occasion of a silver disc award for 10,000 sales of Everyone's Gonna Wonder. On the right is HMV producer Nick Karavais.

NB: When did the studio progress from the mono recorder with the eight channel desk?

FD: In about 1966 we got the first Ampex stereo machine. When we went to stereo we had to build a new mixer for a start. We actually had two stereo machines come to think of it. We used to dub from one machine to the other and each time we dubbed we would add an extra section in, either a vocal or an instrument or whatever. Some of the early recordings had six or eight dubs on them, from tape to tape to tape to tape to tape.

NB: Didn't you lose a lot of quality in that process?

FD: Surprisingly enough I don't think we did, listening to those old recordings now. The evidence is still around, what we achieved with it. All those early ones like the Maria Dallas, Dinah Lee material, all of that was dub to dub to dub. There's an album we did with The Chicks too, I think. All of that early stuff was usually four or five dubs before we got a master.

NB: Did you go to any lengths to try and get separation within the instruments, as they do these days?

FD: Yes, we used to screen things off. But we didn't worry too much abut it. There wasn't really much point in it: all it did was clean the sound up slightly. But what we used to aim for was an overall sound – not individual sounds – a pleasant group backing sound.

We'd try and balance the thing within itself in the studio half the time. You'd stand in front of the instrument or amplifier and listen, and if it sounded all right you place microphones in front and it usually came out much the same in the control room.

Mark Williams in the EMI Studio, Lower Hutt 1976, with engineer Peter Hitchcock

NB: Were you far behind the overseas studios in terms of technology?

FD: Probably, at that stage, five or six years really. But it's amazing when you talked to people from overseas you'd find that really you're not behind. They would do things the same way.

We used to get various people coming over from Britain to discuss recording sessions and how they did it, and you would pick up an awful lot of knowledge that way. They'd just drop the odd little hint about something and you'd try it. There were no books on the subject, hardly any information at all. It was just a matter of perseverance half the time. There was the enthusiasm in those days and it just all happened.

NB: Were you working alone at this point?

FD: Peter Hitchcock did a number of artists also. In those days we shared the recording of local artists. We worked together occasionally. We had to have two engineers on the job to get certain effects. We worked very closely together and we learned by doing – that's inevitable. Peter was a brilliant engineer and was very good at building up equipment. Anything new that came out we'd try and copy it and install it in the studios – some new gimmick to help with production, odd bits and pieces the company wouldn't allow us to spend money on.

NB: What sort of things?

FD: There were all sorts of equalizers built into the desk which weren't on the market in those days. The main aim was to produce certain effects on voices and instruments.

NB: An effect that seemed to be used on a lot of HMV/EMI recordings around 67-68 is that swishing sound known as phasing. I think of Simple Image's 'Spinning Spinning Spinning” and Shane's 'St Paul'. How was that achieved?

FD: This is when you have to have two engineers. You had two tape recorders and we used to vary the speed of one very slowly to put it slightly out of phase with the other one, which gave you that swishing effect. And you had to have someone slowing down the other recorder to make it happen. To get it to happen in the right place was very hit and miss.

NB: How long did 'Spinning Spinning Spinning' take to perfect?

FD: Well we spent one afternoon – it could have been up to five hours. Peter was on the desk and I was on the tape recorder trying to slow it down in the right place to make it go out of phase. Anyway, we got it in the finish after many attempts, many attempts.

NB: On a number of HMV/EMI recordings from that period, such as Allison Durbin's "I Have Loved Me a Man' and some of The Avengers' tracks, there seems to be a harpsichord. Did you have one in the studio?

FD: No it was a piano, We'd slow the tape down and record the piano normally, then speed it up to normal and of course the pitch went up and it sounds a bit like a harpsichord. It was just a gimmick, we used it a lot on different things. With half-speed recording when you speed it up the pitch goes up double so it's still in tune.

NB: How long did it take to make a single in those days? "I Have Loved Me A Man' for instance?

FD: About four or five hours work, that's all. The BLERTA single, 'Dance Around the World' was one evening, maybe four or five hours too. And they were top sellers. It was just something that happened in the studio: you could tell immediately. You had a feeling it was going to be a great hit and it usually was. It was the atmosphere during the actual creation of the things.

Fresh records at HMV, Hutt Road, 1957 - Photo by Morrie Hill

NB: Until the late sixties, production credits were rarely given on records. Who actually produced records up to this time?

FD: Well, quite often someone from the record company, usually a salesman or somebody, would come down with the group, but it was generally left up to the engineer. This went on for quite a few years, until EMI started taking on producers. Howard Gable was one of the first – he produced 'I Have Loved Me a Man'.

After Howard left two years later, Peter Dawkins arrived and Alan Galbraith came in on the scene later. They had their own style and a certain sound they wanted. So the whole thing sort of went away from the engineer being a producer to having a producer there telling the engineer what he wanted.

There's a certain producer I won't name who used to arrive at the studio, we'd get things going he'd take a few puffs of something, disappear under the desk and go to sleep. He'd wake up when we'd finished and say, 'How was it?' We'd play it to him, he'd say 'That's all right', take a few more puffs and go out again. There were a few interesting things like that that happened, but of course the engineers in those days were all innocent – we didn't realise what was going on around us half the time.

NB: There are credits given for various different roles on recordings later in the sixties, such as A&R manager, musical director, arranger, producer etc ...

FD: A&R was artists and repertoire manager, and he was the person who selected the material to be recorded. It was generally a cover version, as there wasn't much original material done in those days. In fact, I think some of the record companies used to hold back releases from overseas and get the local artists to record them. After the local artist had done it they released the overseas one. And half the time they didn't release the original version – to promote sales of local artists.

The musical director was the person who arranged for the musicians to collect at the studio to perform; he often conducted as well. There were several – Don Richardson, Garth Young, Brian Hands. Probably Brian Hands and Don Richardson had the most to do with the arrangements on later LPs.

Rockinghorse in the EMI Studios, Lower Hutt, 1970s - Chris Bourke Collection

NB: In the late seventies EMI shifted their studios to Lower Hutt. How did this change things?

FD: It was a drastic change really. It did a lot of damage to the studios. We had beautiful new studios out there but lost 80 per cent of our clients in the shift. The management of EMI in England said it would make no difference. We had fought against it, tried to get studios built in the Wellington area.

EMI at that stage owned the land in the Hutt where the studio was to be built and they weren't prepared to buy another property and build in Wellington. EMI at the Hutt became basically a manufacturing unit. We did cassette mastering, disc cutting and the odd recording.

NB: Was it a superior studio to the old Wakefield Street one?

FD: It's very hard to say. Some studios give a certain sound. I thought it was superior, but I don't know. The Wakefield Street studio was just a box-shaped room with a very high ceiling. We had curtains all around the walls, Pinex and stuff, probably 25 metres by 50. So it wasn't big at all, but it had a certain sound. I think a lot of the recordings we did at that old EMI studio turned out fairly well, sound-wise.

The Hutt studio was very large – too large I felt for some of the things we did out there. It was all right for orchestral things, with say 20 or 30 players, but for smaller groups it was too big, with too much space between everything. You had to separate everyone to isolate instruments and it led to a feeling of estrangement between players, I think. Whereas at the old studio they were all crammed in together and they had that feeling of being one.

NB: It seems as though there were few rules in the early days of recording, whereas today there's more of a set method.

FD: Yes, well I think there is now and this is possibly why a lot of today's recordings sound very similar. There's no personal preferences that go into it now. It's all set out and you do it that way. At EMI we had all had a go at everything. We tried to give ourselves an interest in everything. If one person wasn't there to do something, someone else could do it. We were all fairly versatile so we could swap over and do each other's job if we had to. It made life fairly easy really, because you could always rely on someone helping you out.

[Courtesy of Nick Bollinger]

1980s advert for EMI Studios

EMI dumped the last vinyl pressing plant in Wellington Harbour. Really?

The last vinyl pressing plant in New Zealand closed down in 1987, and, so the story goes, the plant’s owners EMI dumped it in Wellington Harbour. I’ve heard this story dozens of times from musicians and music fans in recent years. It’s one of those romantic notions that sounds like you want it to be true, especially if you're a vinyl fanatic. Evil corporation destroys local vinyl outlet. But is there any truth in it?

There are several variations on this story – one is that the pressing plant was dumped in Wellington Harbour by a radio station as part of some competition. Another is that EMI dumped it in the harbour to drive up CD sales. Then there’s the tale that when EMI shifted to Auckland in 1988, supposedly the boss of EMI at the time decided to dump all the master tapes of their studio recordings in Wellington Harbour. All of which sound far-fetched – why would a business dump perfectly good equipment in the sea when it was still working and saleable? What really happened to that plant?

Let’s start by asking someone who was there.

Frank Douglas started out working in recording studios at TANZA in 1957, and then later worked at EMI for 34 years running their recording studios in Petone at head office. They had three studios – one for voiceover, one for commercials, and a 16-track studio, which he described as the best in the country.

EMI studios worldwide were all equipped with Neve desks as a standard. When EMI NZ bought it in the early 70s, it cost $80,000-90,000. EMI NZ’s old Neve desk is currently housed in York Street Studio in Auckland.

EMI NZ built a brand new studio in 1975/6 in Lower Hutt. The recording studio was making a lot of money for EMI with local product including Craig Scott and Hogsnort Rupert, so they got whatever gear they wanted. The studios also recorded for other labels including Viking.

After EMI shut down their Wellington HQ in 1988, Frank went out on his own and set up his own studio in Eastbourne, and ran it for close to 15 years. He bought a lot of studio gear off EMI, like mics. His recordings were pressed at EMI Australia. These days he lives in Taranaki and still has a studio in his home, recording mostly country and western acts.

Frank Douglas told me that EMI NZ had 12 presses back in 1987. When the plant closed, the eight newer ones were packed into containers and shipped to Australia – he saw them being packed – and the older four were stripped for parts. What was left was sold for scrap or auctioned off. Their cutting equipment went to Australia as well.

EMI Australia wanted a new cassette setup, and EMI NZ had the best in the world at that time, so that was shipped to Australia at the same time.

Mr Lee Grant in the HMV studio, 1968

Auckland sound engineer and producer Simon Lynch says, “Bruce Ward (EMI’s production manager at that time) was asked about the pressing equipment being dumped in Wellington harbour and Bruce – who would know – knew of no such thing ever happening."

Lynch also pours cold water on the legend that EMI’s master tapes were dumped in the harbour. "All EMI master tapes are still in existence, stored up here in a warehouse which (compiler and local music historian) Grant Gillanders visits regularly for source material for his eclectic compilations."

There are some great photos of EMI’s pressing plant, taken right before it closed down. Author Andy Bassett says, “In 1987, I pitched an idea to the educational publisher I was working for, to write a book about making a record. They gave me the go-ahead. Next day, the news announced the last record plant in NZ was closing down. The publisher sent a photographer down to Wellington the following week and we still got the book out!” It was published in 1988 by Shortland Publications, titled Making A Record.

Music historian Andrew Miller suggests the most likely reason for the legend. "The Pye pressing plant equipment was dumped in the Manukau Harbour in the mid-70s after Pye ceased record operations, a former employee who helped with the operation told me this. PolyGram's Miramar plant went in the early-mid 80s. EMI in Lower Hutt was the last in 1987 with the single 'People In Parks' by People In Parks being the last single pressed there."

Mike Slavin started at EMI in Hutt Rd back in 1984 and saw the closure of their pressing plant unfold. He recalls that “the latter model [vinyl] presses were packed and shipped to Australia. The earlier style were deemed more used and were stripped for scrap.

“The press body itself was the largest part and made of cast metal, and not worth recycling. The harbour story came from the truck driver who picked them up, who said they would likely end up at the harbour reclamation site near Ngaio Gorge, which during 87 and 88, was a large project.

“I was there when one of the units was being loaded. I suppose only the truck driver knows. My understanding is that the last four presses were stripped of scrap [steel], then the press bodies themselves were dumped in the harbour reclamation site [as landfill].

“Almost every worthwhile component from the whole plant was taken to Australia as the Australian managing director [EMI] at the time, David Snell, was ex MD in New Zealand and knew the equipment and its capabilities well. David was from an engineering background and had a lot to do with choice of hardware and maintenance of the plant. He would come in when the main boiler had its yearly service wearing overalls.

“As far as the master tapes were concerned, at the time I was the IT Manager for EMI and the tapes were put into my care and have been for the last 25 years. None were thrown away that had any NZ content.

“I was the last manager and the last division of EMI to leave that site along with the distribution facility. It was very sad watching the Hutt road facility close and at that time I had only worked there four years.”

And that's where the myth that EMI dumped its pressing plant in Wellington harbour has its origins. There's a tiny grain of truth attached to it. Only a tiny one, mind.

Shane tells how Bruno Lawrence was banned from EMI

“I had come down to do a new album, and I thought well Bruno will be playing drums again, on the Straight Straight Straight album and Richard Burgess turned up. They said ‘No, Bruno’s not allowed in the studios anymore. We had a gold disc reception down in Wellington in 1970 for the Loxene Golden Discs. And Bruno’s band were in it, Quincy Conserve, and we had a big luncheon with Loxene, the managing director and his wife and everyone standing around."

“And we all turned up in jeans, it was getting to that era, the long hair and stuff ... and they were put out about that, and of course Bruno had something wrong with his foot, so he was on crutches, and he stuck his crutch in the managing director’s wife’s face and said, ‘Do you wanna bite my crutch?’"

“She was like ‘Aah! Disgusting!’ She complained, and said to her husband, I want that man thrown out. And they tried to tell him to go, and he didn’t want to go. And in the end, he jumped on the table, and they had this big buffet, and they tried to say, ‘Out. Leave. Now.’"

Quincy Conserve in HMV with Peter Dawkins

“Bruno – having had a few drinks – wouldn’t go. He jumped on the table, on the buffet, as we were about to have lunch, and he kicked the food everywhere. ‘You’re nothing but a bunch of phonies, wankers!’ Screamed his head off at everyone. And the band, the Quincy Conserve, you could see them thinking their careers were coming to a fast end here. They tried to drag him off the table, which made it worse. He’s rolling in the food. He was taken out and he was up in the foyer of the theatre up the road, and they dragged him down the stairs still screaming and covered in food."

“So he was barred, and next day we were supposed to be starting on the new album. I’d just come back from the UK. And they said, Bruno’s not allowed in the studio, he’s been barred. Richard Burgess is drumming.”

Burgess, from Christchurch, went on to produce Kim Wilde and Spandau Ballet, and he was in a British group called Landscape that released the unforgettably titled album From the Tea-Rooms of Mars ... To the Hell-Holes of Uranus.

[Courtesy of Chris Bourke]

Chris Bourke on EMI

Thanks to Nick Bollinger, Chris Bourke, Simon Lynch, Frank Douglas, Andrew Miller and Andy Bassett.