After 1963, New Zealand music was about to undergo some big changes. Until then, we had mostly dance bands playing old standards in dance halls throughout the country. They played foxtrots and waltzes and, if they were lucky, they’d be allowed to slip in a “twist” or jive bracket.

Almost overnight, many of the old dance bands were replaced by four piece guitar bands.

There was no booze and everyone dressed up to go out. The music was much the same wherever you went: mostly instrumental with guest vocalists – and it was all for polite dancing.

Then, in late 1962, the first change occurred: we heard The Shadows. Red Fender Stratocasters and Vox AC30 amps, tape echo and dance steps became the order of the day. Almost overnight, many of the old dance bands were replaced by four piece guitar bands. And the music was exclusively for teens.

Then, it all changed again, suddenly and even more dramatically. The Beatles arrived from out of nowhere, followed by The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, The Animals and an avalanche of other British beat groups. No more matching guitars, dance steps or catchy instrumentals. The new groups had a new secret weapon: vocal harmony.

The stage was now set for pop music to explode. There were many changes to come – new styles, new genres, new clothes and new drugs. But by 1964 the global revolution was well under way and there was no turning back.

Meanwhile, out in the provinces …

The new music was huge, not just in the major cities, but also in the provincial centres. Palmerston North was no exception. In fact, by 1964, it could probably boast almost as many great bands and venues as nearby Wellington. And it is here that the story of Sounds Unlimited begins.

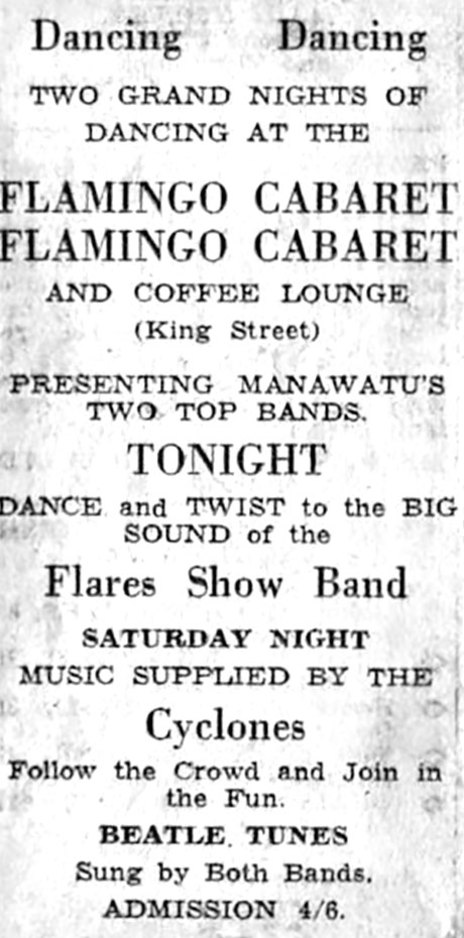

The band that became one of Wellington’s top teen outfits and, according to many, gave rise to that city’s soon-to-be-born underground rock scene, came together in 1965 from two top Palmerston North bands, The Cyclones and The Flares.

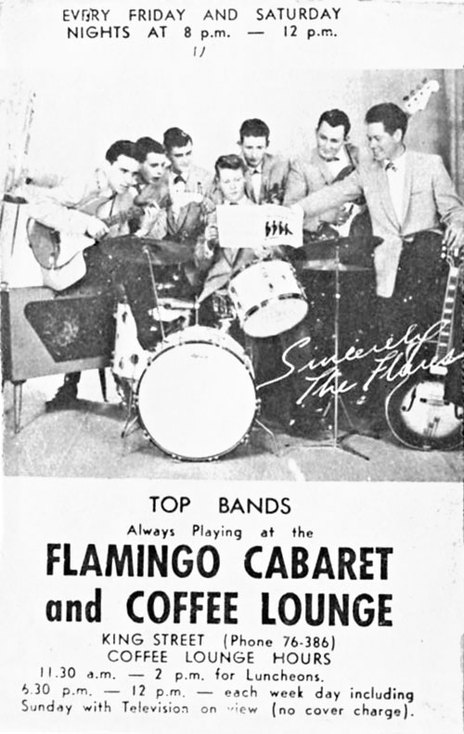

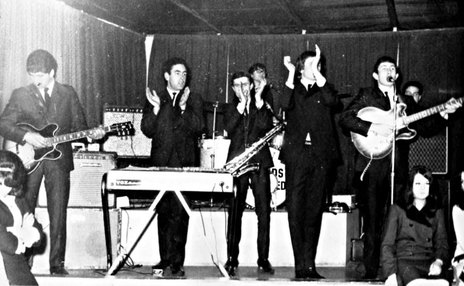

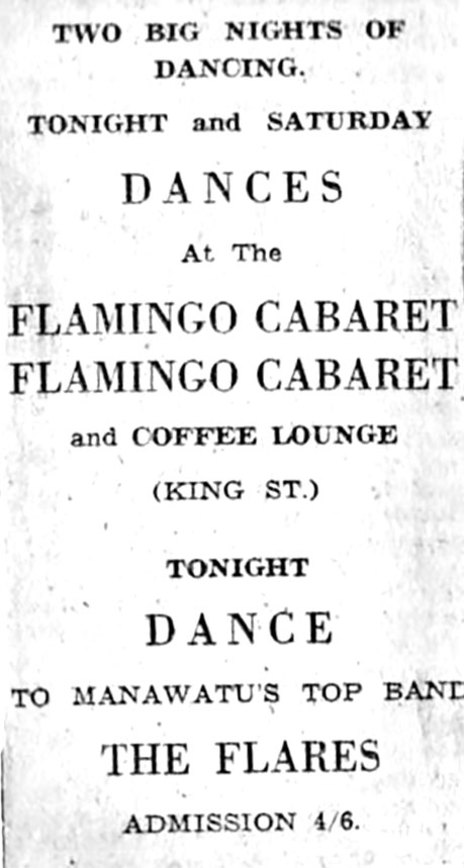

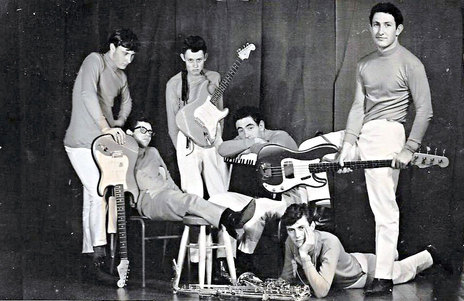

The Flares Show Band was already pulling big crowds at local venues. Members included drummer Maurice Greer (later of The Four Fours and The Human Instinct) and virtuoso sax player Johnny McCormick. They had a big sound that came from a three-piece brass section, in addition to the normal guitar, bass and drums setup.

Meanwhile, The Cyclones got off to a slightly slower start after the first attempts to put a group together in 1962 by bassist/guitarist Mike Findlay with drummer Paddy Beach, and a keen young singer named Bogdan Kominowski, later to become pop idol Mr. Lee Grant.

They were joined by Mike’s elder brother Bernie on piano, and a succession of guitar players who either lost interest or couldn’t handle Mike’s sometimes overbearing perfectionist tendencies. They included (not in any order) Morris O’Keefe, Frank McOviney, Lou Noaro, Ken Climo, Robbie Waite, Mark Tournquist and, later, Mike Griffin.

Playing local venues and winning talent quests got the band fired up for a crack at the big time, but luck was never on their side. In early 1964 Bernie was hauled away to do his national service. In his absence, The Cyclones recruited sax player Johnny McCormick from The Flares and when Bernie returned the band got down to business more seriously than ever.

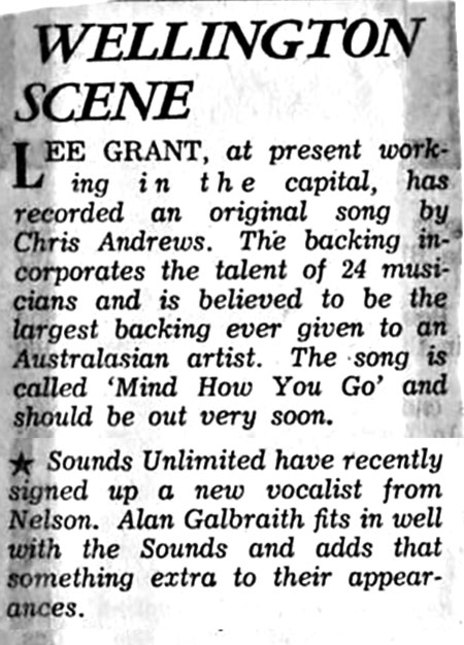

Gigs throughout the lower North Island during 1964 helped the band develop a tight, big sound, perfect for backing the many solo artists appearing on the dance circuit. Bogdan (Mr. Lee Grant) had already been taken out of the band by his new manager and was now establishing himself as a solo singer.

Then in 1965, disaster struck once again when Mike Findlay developed Tuberculosis and spent three months in hospital. Bass playing duties were covered during this time by Don Clarkson (ex-Peter Nelson and the Castaways).

The move to Wellington

After being spotted by Wellington entrepreneur Pat Trott, who worked with promoter Ken Cooper, the band did a few gigs in Christchurch and Wanganui plus a season at Wellington’s Downtown Club before moving to Wellington in January 1966 to take up a residency at The Place.

They were immediately in demand, playing the Ken Cooper circuit of nightspots, often working five nights a week.

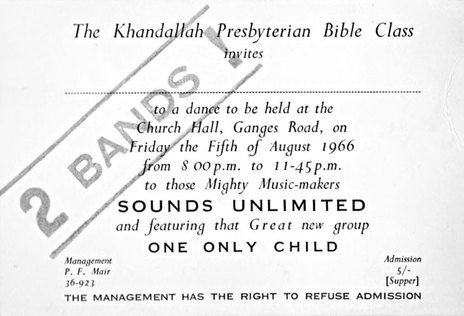

This was a perfect fit for the band, now officially called Sounds Unlimited. They were immediately in demand, playing the Ken Cooper circuit of nightclubs, dance halls, youth clubs and private gigs, often working five nights a week and often twice on Saturdays with a regular gig at the Platter Rack on Sunday nights.

No sooner had they moved than a new lead guitarist was recruited to replace Mark Tournquist. Down on holiday from Gisborne, Reno Tehei sat in with the band one night and was recruited immediately. With Bernie’s newly acquired Vox Continental organ, Johnny’s sax, and Reno’s lead guitar work, the role of rhythm guitar became superfluous so Mike Griffin left and returned to Palmerston North.

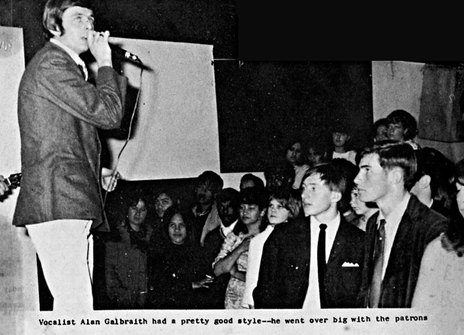

All that the group needed now, according to manager Ken Cooper, was a good front man. Cooper knew Alan Galbraith who had recently started working solo after his Nelson group, the Silhouettes, disbanded. He was flown over to meet the group and joined at the end of May 1966. Sounds Unlimited was now complete.

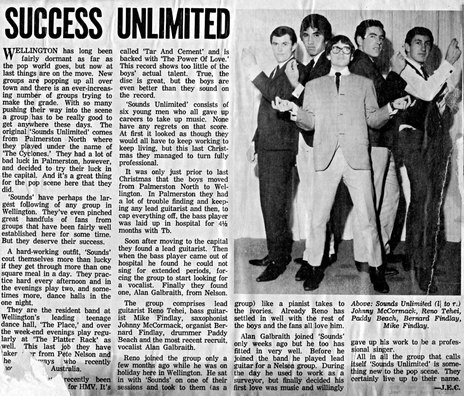

By the time Alan joined, Sounds Unlimited had already released their first single, sung by drummer Paddy Beach. ‘Tar and Cement’ b/w ‘The Power of Love’ climbed to No.3 on the New Zealand Hit Parade and gave the band their first – and only – real hit.

Meanwhile, on the Wellington club circuit they were hugely popular, thanks to a big live sound and eclectic mix of current pop hits. This, in many ways, was also to be their downfall.

The records

Following ‘Tar And Cement’, the group recorded the rather bland ‘Honey And Wine’ b/w ‘Marble Breaks’ and ‘Iron Bends; Long Hair’, a novelty song sung by guitarist Reno; ‘Momma’s A Good Girl’ – the theme for a local TV show – and finally ‘Either Way I Lose’, a rather dramatic big ballad released as Alan Galbraith with Sounds Unlimited. Also in the mix were versions of Buck Owens’ ‘Loves Gonna Live Here’, a pop ditty called ‘Lollipop Train’, Georgie Fame’s ‘Yeh Yeh’, and a couple of other instrumentals.

All in all it was a rather weird selection of songs, chosen by HMV producer Nick Karavias. But to be fair, he struggled with the band’s lack of direction as much as they did themselves. In 1966, very few wrote their own songs. Working the clubs and being on TV meant playing the hits of the day.

The beginning of the end

Despite their obvious musicianship, it soon became obvious that all the members of Sounds Unlimited had different tastes and ambitions. Johnny McCormick was an excellent musician with one foot in the jazz camp; Reno was becoming a guitar hero in his own right; Alan wanted to be a pop star, while the originals – Paddy, Mike and Bernie, were happy just to keep going as a working club band.

Their popularity continued to grow in Wellington, but the end was probably in sight by the time Galbraith’s ‘Either Way I Lose’ was released as more or less a solo effort. But there was to be one last gasp, and this more or less coincided with another big change in the music scene.

Things are getting heavy

When drummer Paddy Beach was called up for his national service late in 1966, Sounds Unlimited retreated to a three-month residency at Nelson’s Galaxy Lounge with drummer Noddy Hutchison. When Beach returned just prior to Christmas, the band was back to full strength and ready for a busy season at the popular beach resort.

Manager Ken Cooper struck a deal to supply a group to play on a return trip to the UK aboard the liner Ellinis.

Sounds returned to Wellington in January 1967 and, before long, disaster struck again. This time it was lead vocalist Alan Galbraith who was hospitalised in early February to have nodules removed from his throat.

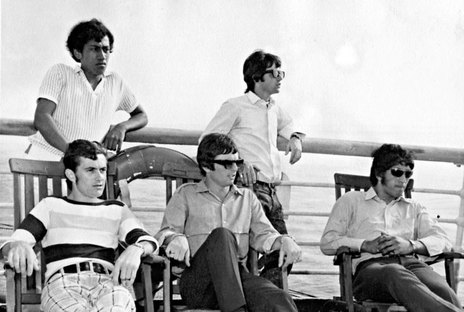

During his recovery, manager Ken Cooper struck a deal to supply a group to play on a return trip to the UK aboard the cruise liner Ellinis. Paddy, Reno, Johnny and Alan were keen to go, but by this time, the Findlay brothers had had enough of the uncertainty of being professional musicians.

Bassist Ben Kaika was recruited from The Bitter End and the new line-up immediately set off for the UK. Galbraith was unable to sing a note for the first two weeks of the voyage due to his recent surgery, but somehow they got by.

After a whirlwind three-week stay in London, sleeping on floors and without money to buy food, the band was due to head back aboard the Australis, but not before gorging themselves on what was happening in swinging London.

They managed to see a number of top live acts including Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Procol Harum, Amen Corner, The Move and Georgie Fame; spent time with EMI and visited Abbey Road; went window shopping in Carnaby Street; nicked a bit of gear, and generally soaked up the madness. Things would never be quite the same again for Sounds Unlimited.

The return home

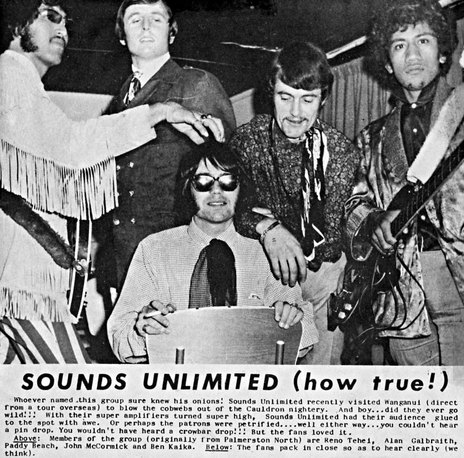

Arriving back in New Zealand in July 1967, the band was hyped as returning heroes – the “loudest band in the land, just back from the UK, with all new amps and a special light show”. More than just a slight exaggeration, but that’s how it worked in 1967!

The new Sounds Unlimited took off on a quick tour that included Auckland, Wanganui, Wellington and Christchurch. In Wellington, the Place had its largest crowd that year and the critics raved. The influence of late-60s British rock was clearly obvious. The old Sounds Unlimited was no more and the weirdness had begun, but the writing was on the wall.

Galbraith’s aspirations to be a pop star and producer got the better of him and he quit. Reno, Paddy, Ben and Johnny formed the Hendrix-inspired Joyful Crye.

Featuring Reno Tehei’s stunning Hendrix-inspired guitar work, the new band quickly gained a big underground following before moving to Australia as Compulsion. (After Compulsion, Reno joined The La De Da's in 1970 for a brief and busy spell.)

Meanwhile, Johnny McCormick returned briefly to his trade as a motor mechanic before joining Wellington’s Quincy Conserve. Alan Galbraith became a moderately successful solo artist before teaming up with Ken Murphy as The Real Thing, and later moving into record production.