Becoming a professional musician at the age of 19, Fraser drummed his way through the 1960s into the early 1970s. He played on recordings by Mr Lee Grant, Kiri Te Kanawa, Shane, Craig Scott, Maria Dallas, Ken Lemon and more.

And having returned to piano, which he had learned as a kid, he became an in-demand keyboardist, arranger and producer. “I was surprised when I heard he had gone back to piano,” remembers Ken Cooper, onetime schoolmate, long-time friend and, for a while, business partner. “‘Jeez Dave, are you sure?’ But he proved us all wrong. He was a very good on piano as well.”

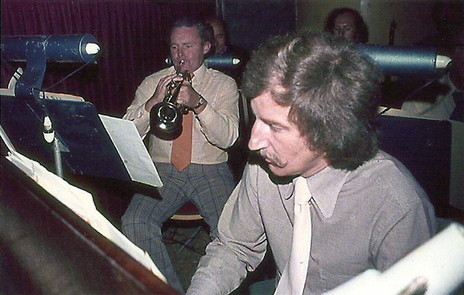

Fraser reflected on his session musician years with National Radio’s Charles Pierard in the mid-1990s. “I used to be in the studio every day,” he said. “It wouldn’t be uncommon for us to record an album in a day. We could have two three-hour calls and we would record six tracks in the morning and six in the afternoon. Even when I hear some of them now they don’t sound too bad.”

Throughout the 1970s and beyond, Fraser’s studio credits continued to expand. As well as Laing’s album, he worked on others by Annie Whittle, the Yandall Sisters, Malcolm McNeill, BLERTA, Gray Bartlett, Tina Cross, Jodi Vaughan and Mark Williams. He wrote and produced movie soundtracks too. His screen work extended from commercials to television docos to the pioneering features of Geoff Murphy.

In the 1970s, Fraser also oversaw stage musicals for Stewart Macpherson’s Stetson Productions. These included The Rocky Horror Show, which brought Gary Glitter to New Zealand and put him on stage with Zero of the Suburban Reptiles.

He also toured the world for many years as the musical director to whistling folk crooner and MOR troubadour Roger Whittaker. This connection came via Cooper, who left New Zealand to become Whittaker’s tour manager in 1982. After occasional forays overseas for Whittaker in the early 80s, Fraser signed on fulltime in 1988 and spent a dozen years helping the singer deliver ‘Durham Town’, ‘The Last Farewell’ and his other ballads to audiences stretching from Las Vegas to Europe to South Africa.

Whittaker made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. “It was one of those situations where I said, ‘I’d like to but it would really cost me a lot of money to give up what I am doing,” said Fraser. “I said, ‘This is what it would have to be’, put the phone down and really didn’t expect to hear anything back from them and it was all accepted and I started thinking, ‘Did I really want to do this?’ Anyway, I did ...”

The lucrative contract eventually helped Fraser buy a lifestyle block near Nelson in the 1990s. There, with wife Linda, he built a house and studio which was also used as an occasional 80-capacity live venue. In 2000, after Fraser returned home to live when Whittaker retired from the road, it was this studio in which The Dave Fraser Trio (with Paul Dyne on bass and Roger Sellers on drums) recorded the album Embrace.

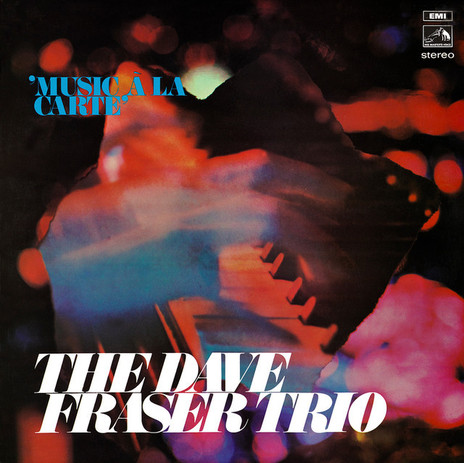

Thirty years previous, an earlier incarnation of The Dave Fraser Trio (with Clive Taylor on bass and Billy Brown on drums) recorded and released debut album Music à la Carte. Produced by Peter Hitchcock, it offered Dave Brubeck-esque interpretations of Beatles tunes and movie themes.

Jazz had been Fraser’s first love. Born in Wellington in 1942, he was raised in Miramar and attended Rongotai College where his father was the woodwork teacher. Growing up, Fraser took classical piano lessons, but it was his time as a drummer in a Wellington Boys’ Brigade band that sent him towards becoming a jazz sticksman.

He left school to become an insurance clerk for AMP. He also started playing the vibraphone, took jazz piano lessons with Bob Barcham and became part of the Victoria University’s jazz club. There, he encountered fellow jazz buffs, Geoff Murphy, Bruno Lawrence and John Charles, all of whom would figure in his later screen music career.

After joining The Nick Smith Trio and playing a five nights-a-week residency Wellington’s Sorrento, Fraser soon flagged the day job. “The upshot of this coffee-bar thing was crawling home at two or three in the morning, five nights a week, and trying to maintain a respectable job in the day go too much and – much to my parents’ regret – I left the AMP,” said Fraser.

Eventually, The Nick Smith Trio tried its luck in Sydney. But Fraser soon opted to come home and head back to the piano, starting on a career path which combined studio session work during the day, on keyboard and drums, and piano residencies in the evening.

Soon, his combination of classically trained abilities and jazz sensibilities marked him out as a very useful man to have in the studio: as the Wrightson brothers found when their January Productions became the go-to team for advertising music and occasional album recording.

Wellington was a pretty small scene then, creatively,” remembers Walsh-Wrightson. “And Dave was an extraordinarily good keyboard player and a really good drummer. He became our third Beatle.

“He was a multi-instrumental guy who could take our arrangements, which we had in our heads – but neither Dale or I were could write arrangements. We would have a block booking every Friday at EMI Recording Studios in Wakefield St and we would just book Dave and three of us would go in there and have the time of our lives.

“We would bring in the [NZSO] strings. We would go through with it with Dave and he would write parts on the spot and go and conduct them. There are some musicians who are classically trained and if you ask them to improvise on anything they would fall to pieces. But Dave would just listen once to something and would immediately get the reference. Sometimes Dave would say ‘Ah, that’s not actually musically correct. But fuck it, it works’ and he would laugh his head off. He was one of nature’s gentlemen.”

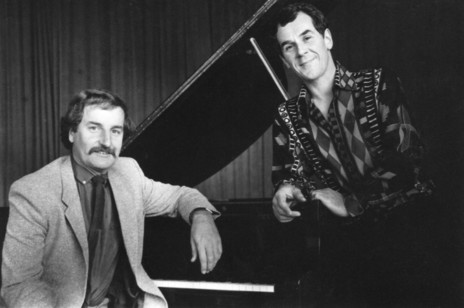

Along with Fraser’s musical adaptability came a business-mindedness. He formed an agency, in which music promoter Cooper eventually became a partner. The pair bought the Beefeaters’ Arms restaurant on the Terrace in Wellington’s CBD, where Fraser had a long residency. After a few years, they sold the business at a handsome profit.

Television and film work also started coming Fraser’s way. “Like everything else I got into, it was by default,” Fraser told National Radio about his move into screen music. “Perhaps there was no one else around who was as bad as me so they asked me. Or possibly I’d fooled enough people for them to think I could do it.”

Among the early film-makers Fraser worked with were Murphy for children's’ series Percy the Policeman and then-National Film Unit director Sam Neill on some of his early docos. Fraser also recorded with Blerta for the troupe’s self-titled television series and for the Blerta-powered films Wild Man and Dagg Day Afternoon, both directed by Murphy in 1977.

The first feature Fraser composed for was the 1977 feature Solo, which he shared with folk musicians Marion Arts and Robbie Lavën of the Red Hot Peppers. Beyond Reasonable Doubt, the dramatisation of the Arthur Allan Thomas case, was his first solo feature score. Other soundtracks included The Lost Tribe, Wild Horses, and 1980s television shows Roche and Inside Straight. He produced John Charles’s soundtracks for the Murphy movies Utu and The Quiet Earth and produced Charles’s score for Bruce Morrison’s Constance. Writing music for the screen, he said, “is a very ordered discipline to get into. I enjoyed that discipline.”

David Gerald Fraser died of a brain tumour in Nelson in October 2002. He was 60.