Throughout all his work, in many media, Baysting’s understanding of and commitment to New Zealand is apparent. As a scriptwriter, songwriter or standup, the character he has created is a New Zealand everyman, “waiting for the bus” that never comes, that “can’t get back”. He champions the craft of songwriting and the instrument he promotes is the most democratic: the ukulele.

Born in Blenheim on 17 April 1947, Baysting grew up in the Nelson area in the 1950s and 60s. His father, also Arthur, was born in Portsmouth, and emigrated via Australia where he met and married Mary; they had four children including twins Arthur and Merril. Arthur Snr worked for the forestry service, and his son remembers a bucolic childhood spent in swimming holes and the bush. He was keen on sport, especially cricket, playing behind the stumps in a schoolboy league competing with future New Zealand wicketkeeper Ken Wadsworth.

On the radio was The Goon Show, a pivotal influence to his generation. Small for his age, Baysting found that humour fended off bullying. Living in Tahunanui, out of Nelson, he saw many live shows and entertainment from the old, eccentric New Zealand. Among them were ex-Kiwi Concert Party comic Stan Wineera – who would swallow a lit cigarette and then blow smoke out his ears – and the Howard Morrison Quartet, whose guitarist/songwriter Gerry Merito epitomised a knowing, deadpan New Zealand humour. He witnessed drag act Noel McKay, and the East Cape’s Rama White, a R&B belter best known for the bilingual ‘Language Song’. New Orleans music was already a favourite via Fats Domino and the visiting, vocally dextrous singer Clarence “Frogman” Henry.

Baysting has never entertained the idea of a cultural cringe.

Popular on radio during his childhood were New Zealand novelty songs that were a genre unto themselves, written by specialists in “kiwi vernacular” such as Ken Avery (‘Tea at Te Kuiti’), Peter Cape, and Rod Derrett. The quality of local music meant Baysting has never entertained the idea of a cultural cringe.

Leaving Waimea College with a goal of becoming a writer for the NZ Listener, Baysting moved to Wellington, joined the NZBC as a junior clerk, and boarded at the Public Service Hostel at the end of Oriental Bay. To Michael Colonna he recalled: “I loved it there because you could walk everywhere and I spent many evenings at the nearby Chez Paree and Monde Marie folk clubs. I also started writing for other performers including blues singer Val Murphy, and for folkie John Reilly, who later joined Hogsnort Rupert.

“Eventually the Listener took me on as a cadet journalist and I gradually worked my way up to doing interviews and more pop culture stories. In order to attract younger readers the editor, Alexander MacLeod, gave me the back three pages. I remember when Jimi Hendrix died, I stayed up all night and wrote a story about him that got a good reaction. We ran the Top 20 music chart and I got Ray Columbus to do a weekly column. I also got a photo of John Lennon on the front cover which shocked a few readers. Hone Tuwhare, James K Baxter and a few other writers and poets used to pop in now and then to visit Noel Hilliard, the chief sub-editor, for a coffee and a chat.”

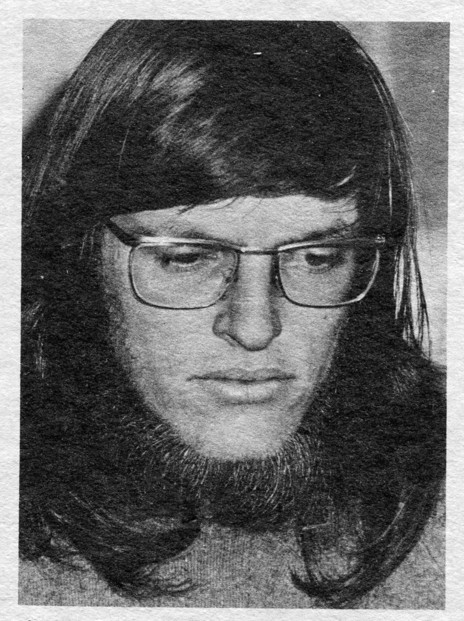

In 1971 MacLeod gave Baysting a pseudonymous column reviewing pop and rock, called ‘Grooving with Moog’. (In 1968 Baysting had written some reviews for the short-lived music magazine Third Stream.) His Listener columns show no hint of post-Beatles malaise; instead he has an astute eye for the best of the age: Rod Stewart without a dull moment, Paul McCartney in the heart of the country, Randy Newman burning down the cornfield, and “At last – a female rock band!” (the staunch blues-rock group Fanny). Two albums from this period stayed with him as templates for simple, heartfelt songwriting delivered from a back porch setting: Bobby Charles, and Link Wray’s Beans and Fatback. Other influential songwriters at this time were Chuck Berry, “the greatest rock poet”, and Buddy Holly – for the rhythm.

In 1970, at a students’ arts festival, Baysting met Jean Clarkson, who was studying printmaking at Elam in Auckland. They married the following year, and settled in Auckland, with Baysting relinquishing his Listener job. “Since 1971 Jean and I have worked together as a team,” he says.

Baysting had his horizons widened by the creative people he met at Elam. At one fancy dress party, he went as a bodgie out on the town, wearing a blue lurex shirt and black stovepipe trousers, with winkle pickers. It was the first hint of the future Neville on the level. Clarkson introduced him to fellow Elam student Sally Rodwell, whose partner Alan Brunton had been publishing local poetry and organising public readings of the new young poets. They became friends and Baysting became part of the Auckland literary scene.

At one early 70s fancy dress party, he went as a bodgie out on the town, wearing a blue lurex shirt

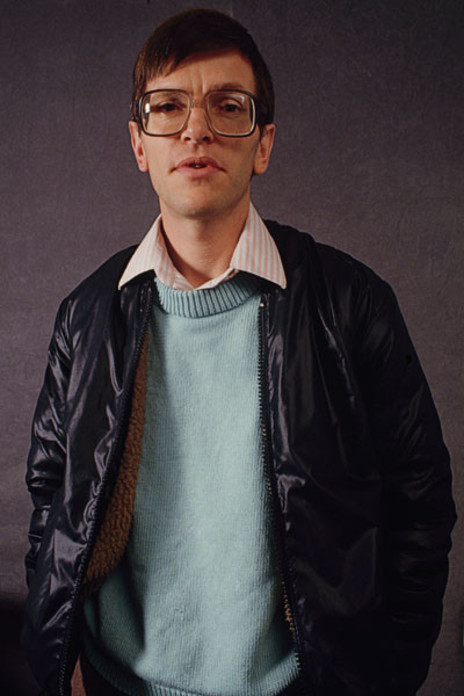

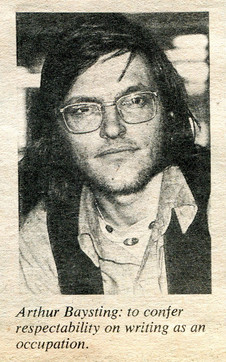

Baysting joined a group of young poets such as Murray Edmond, Russell Haley, Sam Hunt, David Mitchell, and Ian Wedde. His own public readings were well received and many poems appeared in literary magazines. With his wife Jean – and the help of Elam typographer Robin Lush – he hand-set and self-published his only collection Over the Horizon (Hurricane House) in 1972. Bert Hingley, later a trailblazing publisher of New Zealand fiction, wrote in Craccum that a “wry vision” was among the poems’ virtues. “Baysting’s voice is distinctive. He has found a style of his own and his poetry is remarkably free of the pretentious and intellectual posturing which often mars the work of young writers.”

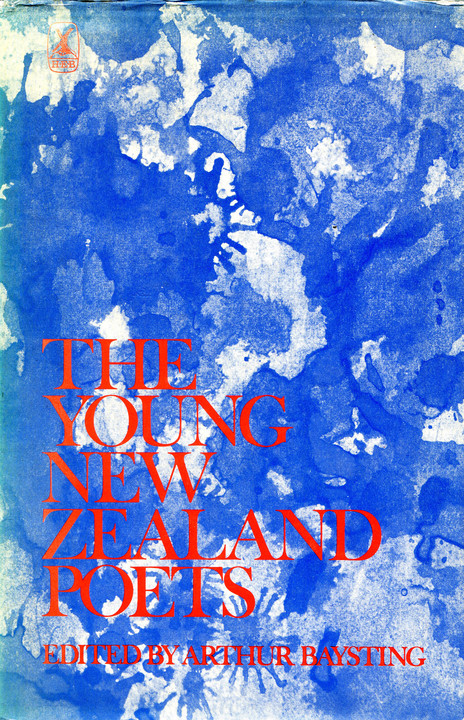

For Heinemann, in 1973 Baysting edited a timely and influential anthology, The Young New Zealand Poets. Writing in 2019, New Zealand literature scholar Mark Williams commented in Pantograph Punch that Baysting “had the necessary mixture of subversiveness and authority to make his entry both a challenge to eminent voices (Allen Curnow or James K Baxter) and a welcome announcement of fresh ones. His book had chutzpah, too … Certainly, the democratic distance of Baysting’s anthology from Curnow’s high-toned Penguins was exhilarating.”

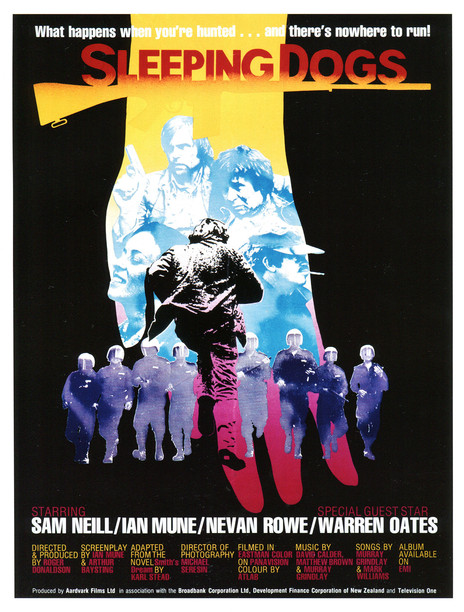

Baysting became a feature writer on Thursday, edited by Marcia Russell as a feminist alternative to NZ Women’s Weekly. While at Thursday he reviewed a 1974 TV drama called Derek, written and directed by Ian Mune and Roger Donaldson. Letters to the editor described it as “uncouth” and “garbage”; Baysting was more complimentary, and predicted the drama would win a Feltex award, and antagonise morals campaigner Patricia Bartlett.

Both happened, and Mune – who had noticed Baysting’s poetry, and a teleplay he wrote that year, A Bed for the Night – approached him to collaborate on scriptwriting. Donaldson and Mune were producing and directing Winners & Losers, a pioneering series of dramas adapted from classic New Zealand short stories. Baysting wrote the scripts for Frank Sargeson’s ‘A Great Day’ and Maurice Shadbolt’s ‘After the Depression’. (Baysting and Mune also co-wrote the award-winning The Mad Dog Gang Meets Rotten Fred and Ratsguts.)

In 1975 Baysting and Clarkson left New Zealand for a working OE: he had been hired by film director Warwick Brock to research and write a documentary about the ecological fate of the Earth, called Paths to the Future. The couple drove across the United States – sleeping in their station wagon – and also visited Mexico and India, talking with futurists from all walks of life. Returning to New Zealand after a year, Baysting found his appreciation for its culture and society was invigorated.

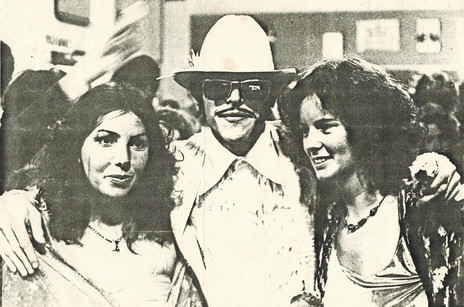

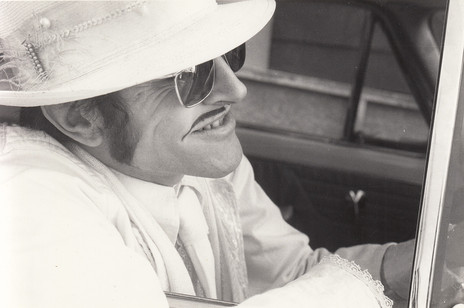

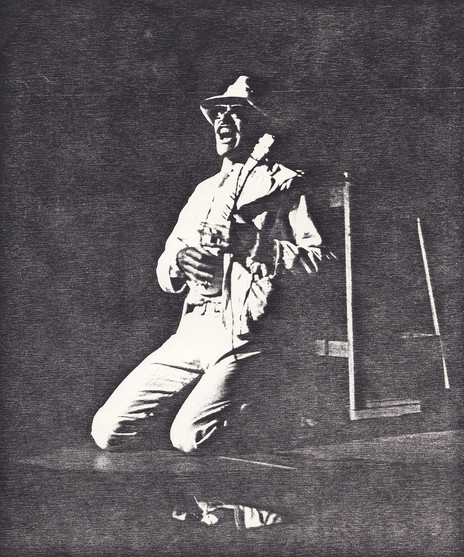

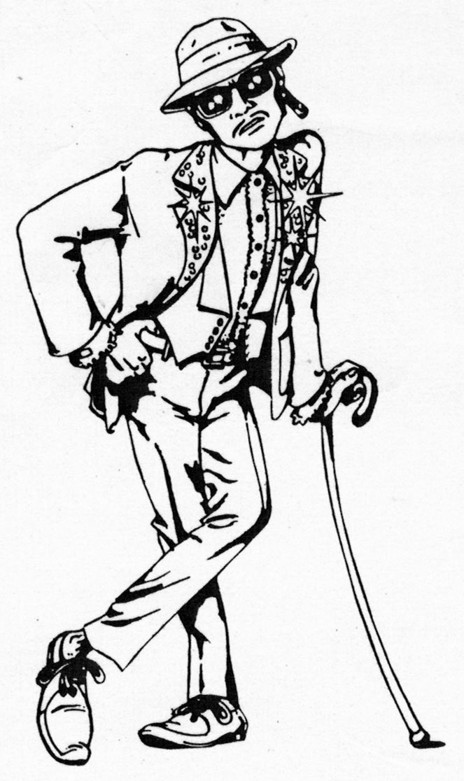

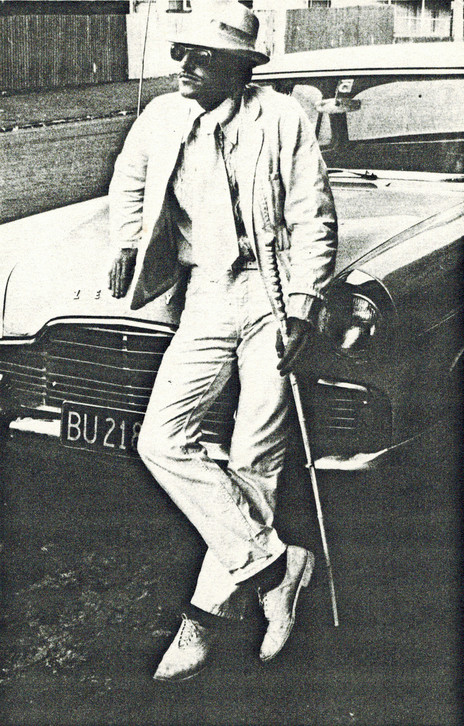

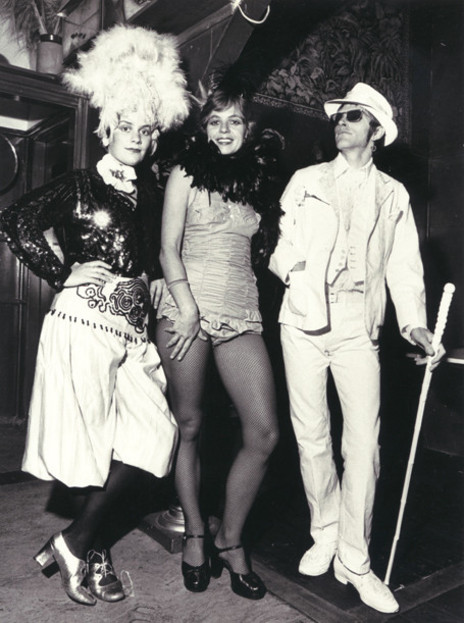

Donaldson and Mune recruited Baysting to co-write the script of Sleeping Dogs, adapted from C K Stead’s novel Smith’s Dream. The 1977 feature would revitalise the New Zealand film industry. In his autobiography, Ian Mune describes seeing on the red carpet at the premiere a fellow dressed in a “white suit, pencil moustache and Tyrolean hat, both dapper and sleazy”. It was Baysting, in character as Neville Purvis, the Naenae bodgie and graduate of Mt Crawford Finishing School, who was then holding court as Red Mole’s MC at Carmen’s Balcony in Wellington – no longer a strip club but a cabaret.

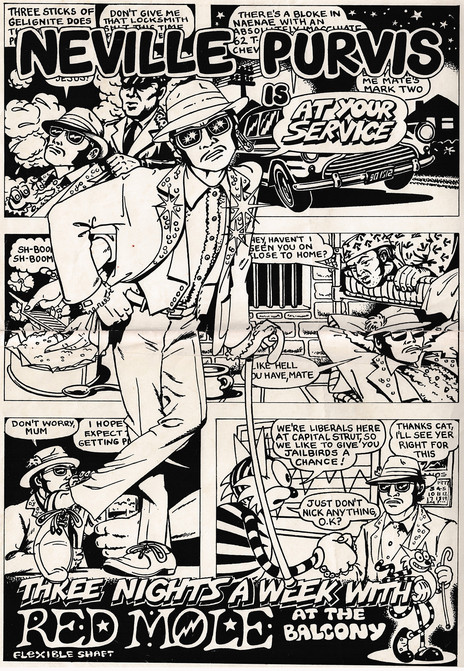

Red Mole’s seven-month residency at Carmen’s Balcony was a seminal event in the city’s entertainment history. Baysting was invited to be the MC by the theatre troupe’s founders Alan Brunton, Sally Rodwell, and Deborah Hunt. The all-white Neville Purvis costume was created by Clarkson. It enabled Baysting to play a provocative spiv, ingenuous to any offence caused and not the brightest bulb in the nightclub.

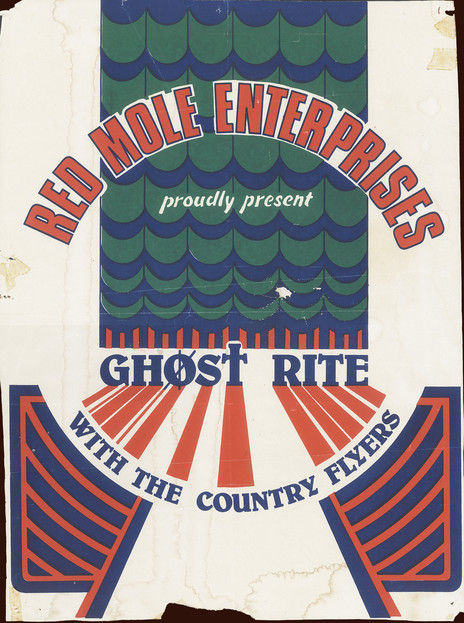

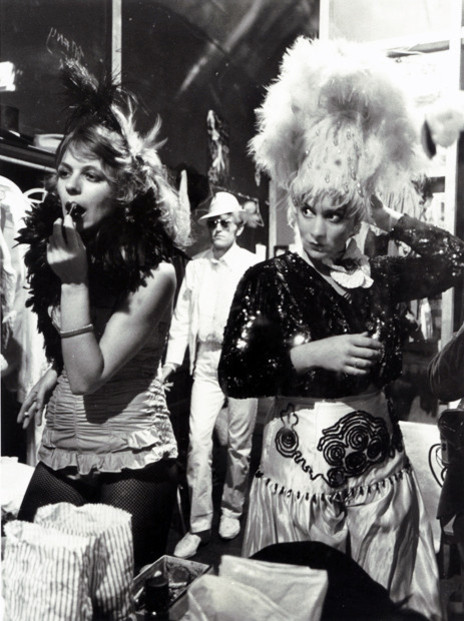

The talent on display was formidable: these theatrical pros could combine drama, dance, comedy and even fire-eating. On opening night, Sunday 13 March 1977, the show was called Cabaret Capital Strut – and the residency kept getting extended, to several nights a week. Pasted on lamp-posts throughout the CBD were striking, risque posters by graphic artists such as Clarkson, Joe Wylie, and Barry Linton that made the cabaret’s presence unmissable. Crowds queued down the street, waiting to enter a den of iniquity that few normally braved other than lonely drunks and visiting seamen. During the residency the troupe created and performed six original shows. Guest artists came and went, among them Andy Anderson, Beaver, Rick Bryant, and actors Cathy Downes, Bill Stalker, and Susan Wilson. In all, 47 performers participated in the series of shows.

Murray Edmond, a Red Mole veteran, recalls, “The Balcony was an exciting place to be: crowded, smoky, with mirrored walls shrouded in the deep reds and golds of Carmen’s theatrical tat.” The scene had the atmosphere of art cabarets from 1890s Paris and 1930s Berlin and, on stage, “Red Mole spliced Kiwi drollery and Kiwi sentiment with the low-life, high-art end of European Modernism. For Red Mole cabaret was vulgar, using low humour and a democratic impulse to slaughter sacred cows, both social and also dramatic. Red Mole’s cabaret went looking for a new kind of theatre in the past.”

At first, Baysting was petrified, as he mustered the actors on and off the stage at Carmen’s Balcony

At first, Baysting was petrified, as he mustered the actors on and off stage. He learnt to deal with drunken hecklers – “keep taking the pills” – and with Neville’s naïve self-belief overcame his nerves. “No talent, but a ton of charisma.” Other catchphrases cemented the Neville character: “Neville on the level”, “Purvis at your service”. Cousin Sheryl – Clarkson – was his trusty sidekick. In the Listener, arts reviewer Ian Fraser described Purvis as “a dazzling comic creation”. This stale breath from the 50s deserved to be “as successful and durable as that other original, Fred Dagg.”

Edmond credits the success of Cabaret City Strut to three factors. The satire was topical and political; Robert Muldoon was only 14 months into his stint as prime minister, but had already provided years of material. This brought out the liberal audiences, who would usually have gone to Downstage rather than a fading strip club. Music was the second factor: there were many guest musicians, but Midge Marsden’s Country Flyers, who held court at the Royal Tiger until 10.00pm – became the mainstays. (The Flyers’ Neil Hannan was musical director. They would later follow Red Mole to Auckland and then New York, become Red Alert with Jan Preston and eventually evolve into The Drongos.) Edmond also says the forbidden sexiness of the venue was a vital factor: Hunt and Rodwell’s s&m dance to J J Cale’s ‘Cocaine’ was very popular. “Topicality plus rock music plus sexiness was a winning formula in the heart of Wellington.” Phil Warren visited Carmen’s and contracted them to a long season at Auckland’s Ace of Clubs.

The work with Red Mole accelerated his interest in songwriting. The actors and band would often quickly have to re-write hits – or create new songs – to serve the dramatic action and skits. Two stood out. Baysting based a script on a Frank Sargeson short story about a son who has long ago stopped visiting his hometown; every Friday night his mother meets the bus in the hope of seeing her son. Baysting’s interpretation featured Willie Nelson’s recent hit ‘Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain’. Another dramatic piece recalled the infamous 1964 murder of a gay man in Hagley Park, in which six teenagers, waiting near the toilets, had beaten him to death and claimed he had accosted them. A jury acquitted them of the charges. In Baysting’s script, the soundtrack to this choreographed atrocity was a medley of Beatles songs, including ‘Love Me Do’. Baysting would often throw lyrics into the pool. The experience, he later said, meant “I became a songwriter. I was a poet, but I haven’t been since Red Mole.”

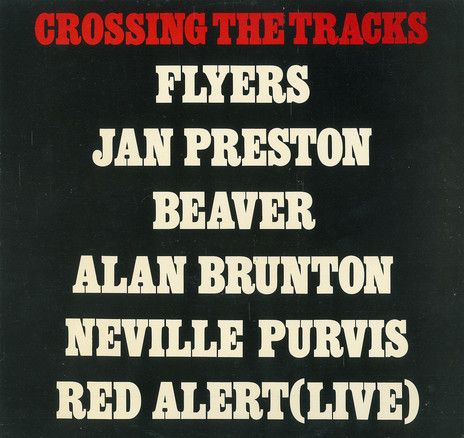

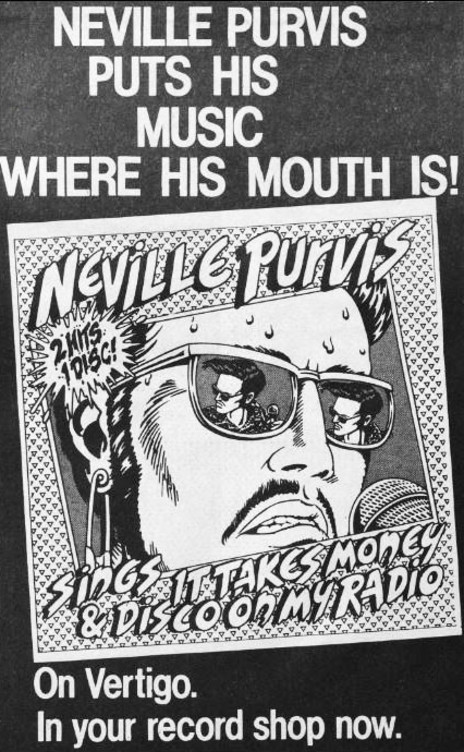

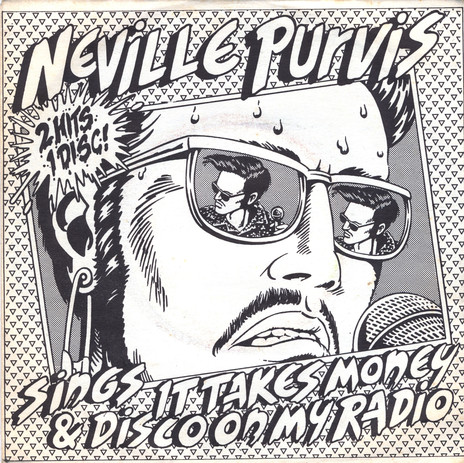

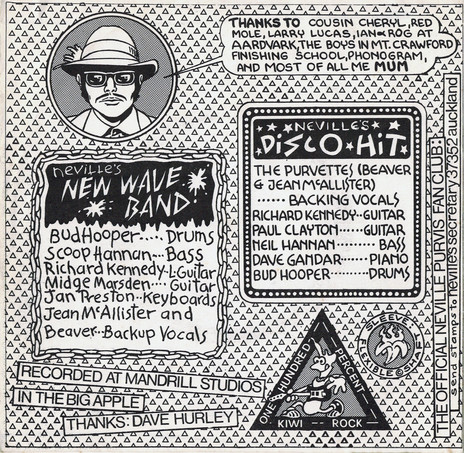

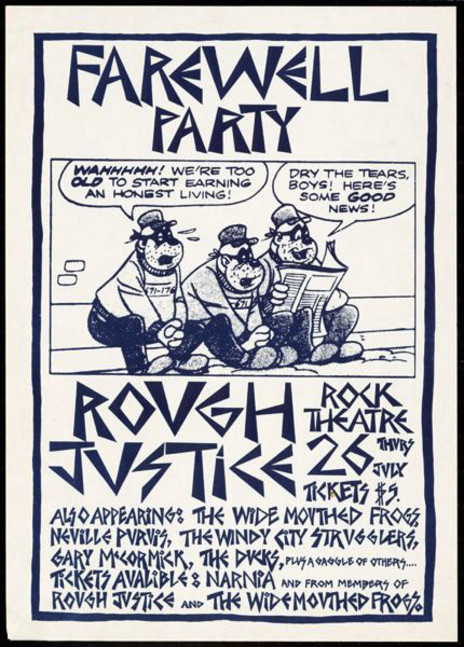

For a two-year period, Neville Purvis seemed ubiquitous, like a welcome – if uninvited – guest. He wrote a column for early issues of Rip It Up, acted in a yoghurt ad, appeared a few times on TV’s Eyewitness as in-house comic, featured on the Red Mole live album Crossing the Tracks, and released a single on Vertigo, ‘It Takes Money’/‘Disco on My Radio’. (A video directed by Donaldson has been lost; the B-side was a parody of “Bee Gees’ disease: white disco.”) He performed at Nambassa and went on tour with Rough Justice and The Crocodiles. In March 1979 Rip It Up’s ‘Rumours’ column asked, “Can it be true that our intrepid hero, Neville Purvis, has retired to the West Coast? Some say he’s preparing for his TV One series. Methinks Neville merely decided against his annual holiday at Mount Crawford.”

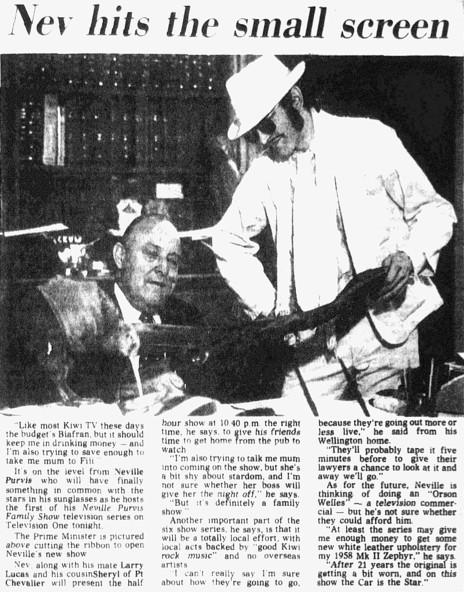

Television came calling, and the six-part series The Neville Purvis Family Show was unlike any other New Zealand comedy series before or since. Baysting would later regret it, not for the show’s most famous moment, but because Neville and Avalon were an uneasy mix. The idea was to have The Crocodiles as the house band, but this did not fit with Avalon’s plans. And there were many watered down sketches and compromises.

The series opened with Muldoon – the actual politician – cutting a ribbon to launch the first episode (Neville was a National supporter). Neville then suggested they go downstairs for a quick lager at Bellamy’s. “Good idea,” says Muldoon. Far from a family show, the series became cult viewing for true believers rather than gobsmacked viewers. Support actors such as Bruno Lawrence, Ian Watkin (formerly with Blerta) and Marshall Napier (playing Neville’s sidekick Larry) went on to long careers; as Clarkson didn’t want to be on television, Liz Tolley played cousin Cheryl.

With the exception of the Sunday Times’ “Marlowe”, the critics hated it. Most apoplectic was Barry Shaw of the Auckland Star (father of Andy Shaw of Here’s Andy fame), who spat vitriol at every episode, giving the show great publicity. Each week he vented his displeasure and Neville quoted his criticisms as if they were the highest praise.

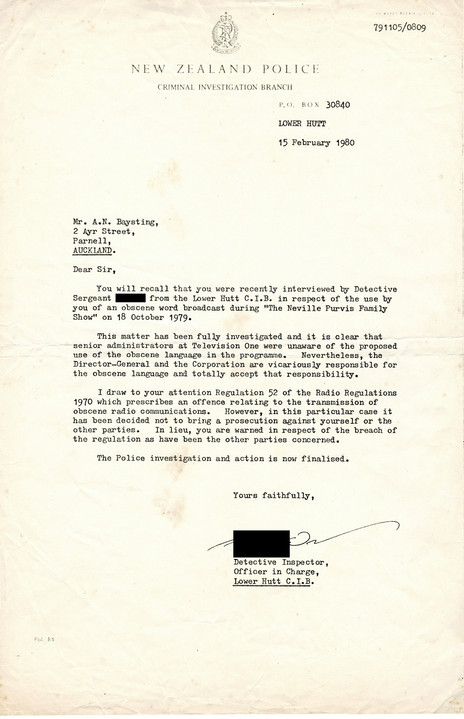

The most famous moment in the series came in its closing seconds on 18 October 1979. Neville read out some of the readers’ letters complaining about the bad language, and apologised to camera. Then he turned to Larry and said, “You reckon that should do it? At least we never said fuck.”

“Sewage humour a new low!” screamed ‘Truth’.

“Sewage humour a new low!” screamed a Truth headline: the degenerate series had set “a new standard in debasement”. TVNZ’s director-general Alan Morris apologised for the “inexcusable behaviour”. Avalon received only three letters of complaint but, according to the Dominion, word “came down from above” to the TVNZ board. The bodgie had bolted: the series was already over. But Baysting was summoned to the Lower Hutt police station to discuss the Radio Regulations Act 1970, part of which prohibited the broadcasting of obscene material. After four months, the police decided not to prosecute, but issued a warning to Baysting, and to the TV executives, who were “vicariously responsible for the obscene language.” (Neville may have been the first to intentionally use the word but, ironically, a policeman apparently got there first the previous decade, when it slipped out during Joe’s World, a live-to-air children’s programme.)

The Neville Purvis Family Show was nominated for a Feltex award, and Barry Shaw spluttered one last time, describing it as “a sick joke”.

Baysting barely touched ground in 1979. During the year, he appeared at a broadcasting conference – dressed as Neville – and said that New Zealand should export music acts rather than dead cows. His friendship and co-writing with The Crocodiles turned into a quasi-management role, which was soon passed on to Mike Chunn, and on their two albums the group thanked him for songs, inspiration, “and rugged talks”.

One song in particular marked the shift to the next phase of Baysting’s career: songwriter and champion of New Zealand music. ‘Tears’ – co-written with Fane Flaws, formerly with Blerta – reached No.17 when released in 1980. But, like one of the placards Bob Dylan holds up in an early video, the song was like putting out a slate: Baysting was now a professional songwriter.

Baysting’s dedication to songwriting intensified, and his productivity can be seen on the co-credits he receives on songs recorded by the Crocodiles, the Pelicans, Bill Lake, the Windy City Strugglers, Beaver, Margaret Urlich and many others. In 1973 he co-wrote, with Graeme Collins, the first solo single of Marc Hunter of Dragon, ‘X-Ray Creature’ (Family). Others he has written with include Midge Marsden, Che Fu, Dragon, Glen Moffatt, Jenny Morris, King Kapisi, Marina Bloom and Suzy Cato.

Among those who have recorded his songs are Anne Kirkpatrick, Boh Runga, and Che Fu. Songs of which he is especially fond include ‘Rangitoto’ (performed by the Red Mole band), ‘When the Circus Came to Town’ (co-written and recorded by Al Hunter), ‘Can’t Get Back’, ‘Waltz of the Wind’, and ‘If I Was Thirsty’ (written with Lake and recorded by the Windy City Strugglers), ‘Waiting for the Bus’ (written with Lake, recorded with the Living Daylights). As documented in Costa Botes’s documentary Struggle No More, about a songwriting trip to Ohakune, many of Baysting and Lake’s songs are short stories set to music.

In 2014 the Australian Play School presenter Alex Papps released a CD of songs by Baysting and Dasent, Let’s Put the Beat in our Feet, with one song, ‘Bananas’, being a collaboration between Baysting, Dasent, and James Reid of The Feelers. One early and lasting musical friendship was formed when he met Opetaia and Julie Foa’i of Te Vaka at a songwriting evening in the 1980s.

Baysting has also written instrumentals such as ‘Man on a Grey Couch’ from Peter Dasent’s first Umbrellas album. He has also written many songs with Tony Backhouse, including gospel songs for Backhouse’s Sydney choir The Café at the Gate of Salvation, a group which inspired many other a cappella choirs in New Zealand and Australia. One co-write, ‘All of Heaven’ was written on South Island’s West Coast in 1979, the same year as ‘Tears’ – it is still sung today and is featured in many of Backhouse’s international gospel choir workshops.

Immediately after the Neville Purvis Family Show finished, Baysting found that work commitments – as a performer and a scriptwriter – started to get cancelled, and then dried up. He and Clarkson left for Australia, where they supported each other as the work came and went in their fields of writing and printmaking. He signed a music publishing deal with Mushroom, alongside others of the Crocodiles fraternity.

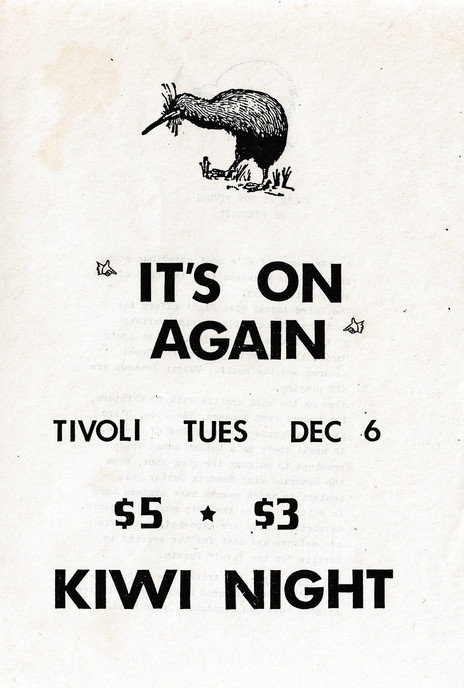

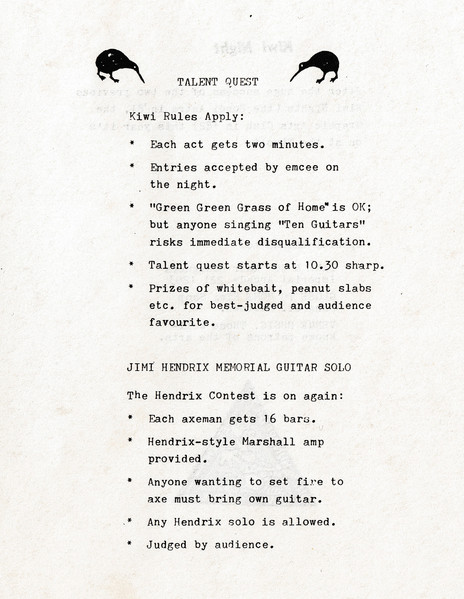

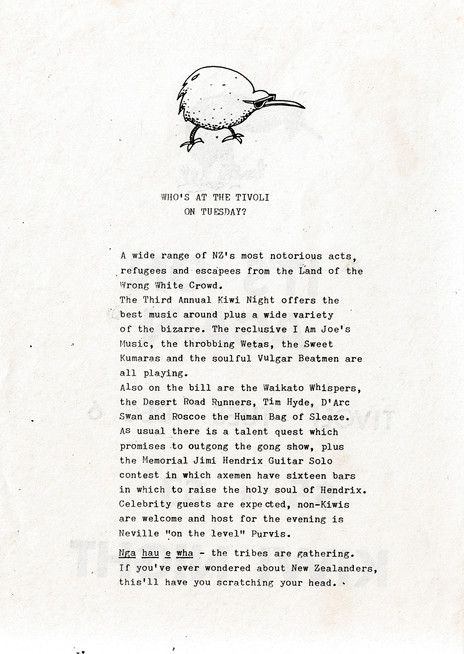

Baysting’s connections with New Zealand musicians in Sydney led to the establishment of an annual Kiwi Night, in which expatriate musicians and friends gathered in a pub for a spontaneous variety show. Among the many performers who took part were members of the Crocodiles, Mi-Sex, plus Dave Dobbyn, Brent Eccles, Mike Caen of Street Talk, Robert Taylor and Marc Hunter of Dragon, and Max Cryer. A highlight of the evenings was the annual Jimi Hendrix Memorial Guitar Solo contest, in which participants were given 16 bars “to raise the holy soul of Hendrix”. Prizes during the night were mussels, Whittaker’s peanut slabs and Wattie’s baked beans, and the house wine was Steinlager. Neville also ran a competition for the first person to correctly sing the 1968 Chesdale cheese jingle: “We are the boys from down on the farm …”

Talented people should leave New Zealand, attend the university of life, and then come back.

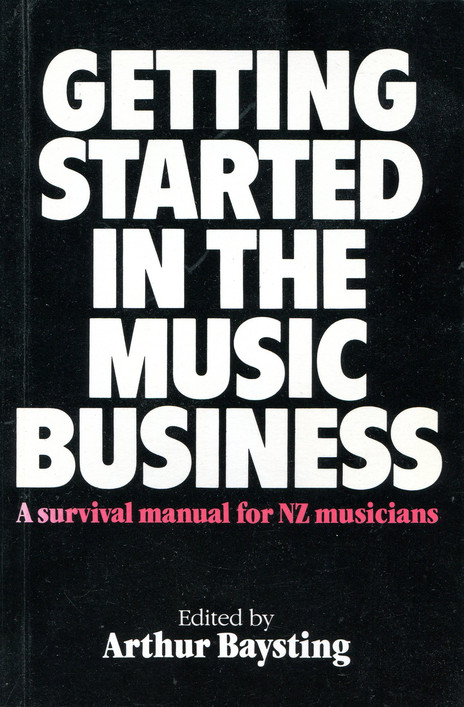

Baysting and Clarkson returned to New Zealand in 1985, settling in Grey Lynn where their home became a magnet for artists, musicians, and writers, wanting to discuss ideas, plans, setbacks, families. They leave with moral support and usually a strategy. An early example of Baysting’s inclusive approach was the Kiwi Music Convention in 1987, at which 300 musicians and members of the radio, music and retail industries gathered to discuss how the dismal interest in New Zealand music could be improved. The panels featured the top rank of industry players, in creativity, management, record companies, performance and promotion. “Over the next two days,” Baysting wrote, “delegates talked, listened and argued. Tempers sometimes got frayed but recommendations were made. Since then, some of them have been fulfilled.” In 1989 Baysting edited the frank, often testy discussions into a book, Getting Started in the Music Business (Ode).

Visiting New Zealand during this period, Baysting told Salient editor Sally Zwartz about what he’d learnt from being immersed in Australia: self-sufficiency, and the idiosyncratic New Zealandness of its artists. “Don’t write the story about me,” he said. “Write it about all those other people.” He was referring to the musicians and artists “stranded in paradise”, aka exiled in Australia seeking warmer pastures. Talented people should go away, he thought – attend the university of life – and then come back. “Because you can’t see New Zealand until you’re outside of it. I never knew New Zealand until I went away. I didn’t have any feeling for it.” Early on he thought New Zealand was a good place, “but a goldfish pond,” and the world was amazing. Living away, he realised “the world is the world, and New Zealand is amazing.”

Freelancing for the Gibson Group production company, Baysting wrote scripts for the Public Eye series, and the TV dramas Undercover and The Returning. He worked for the anti-smoking lobby group ASH, and for a couple of years was Helen Clark’s electorate press secretary, until she became a cabinet minister in 1987. For two years, from 1992, he was president of the New Zealand Writers’s Guild.

One result of his working with Helen Clark, was the commissioning of a book by the Oxford University Press, Making Policy … Not Tea. Publishing in 1993, this was a book of interviews with women MPs. With the help of broadcasting librarian Margaret Dagg and Flying Nun fan Dyan Campbell, Baysting interviewed past and present women MPs about life and politics. Many MPs welcomed the chance to speak frankly about the life in an essentially male bastion. Interviews for the book threw up interesting trivia. Ruth Richardson wrote “the mother of all budgets” listening to Patti Smith and, after a hard day’s work, Helen Clark likes to relax with opera or Ry Cooder. The book was well received and drew international interest when the BBC World Service ran a feature on it. They interviewed several MPs including Marilyn Waring and other figures. Clark’s experiences were also highlighted and her honest account of the Lange and Roger Douglas period was an early description of what went on during this tumultuous period.

Also in 1992, Baysting was voted onto the Apra board as New Zealand writer-director, a position he held for 18 years. Being the only New Zealand member on an Australian corporate board was difficult. At the first board meeting he was met with sheep jokes, but he soon began advocating strongly on behalf of New Zealand songwriters. There were regular international conferences and he insisted on attending them all, as the only person who could represent New Zealand musicians on an international stage. Mixing with the top level of industry executives gave him an inside view of the international industry.

In the 1990s, many initiatives took place that changed the status of local music.

Baysting’s time at Apra coincided with the appointment of Mike Chunn as general manager, and together they put many initiatives in place that changed the status of local music. The Apra Silver Scroll Awards became a major event, and the songs were the focus of attention. The duo worked at improving airplay for New Zealand music, and diversity in the industry, and instituted new awards such as those for Maori, country, and children’s music. Baysting and Chunn were closely involved in launching the Ukulele Festival, along with Marie Winder, the late Bill Sevesi and other music teachers, and getting the instrument into schools.

Baysting and Chunn gathered other musicians around them and soon almost everyone was talking about quotas and a youth radio network and much more local content in film, radio and television. The duo led a steady stream of lobbyists down to Parliament. They knew that they were guaranteed a sympathetic ear when an MP saw a chance of a photograph with a celebrity. With the help of Debbie Little, Petrina Togi-Sa’ena and a volunteer group of Apra staff, a fundraising night was put on at the Town Hall. The night raised nearly $20,000 and the Green Ribbon Trust was solvent.

At Apra, Togi-Sa’ena worked alongside Baysting from 1994, and saw the influence and impact he has had on New Zealand music. “A lot of the value and strength of our local industry today is testament to the work achieved by Arthur and Mike,” she says. “He is fiercely protective of songwriters, and countless careers were positively affected and supported by Arthur. His own songwriting and script writing experience gives him an understanding of songwriters and their creative process, and he understands the influence of music on our culture and its impact for our sense of identity and pride in where we came from.”

In 2010 Baysting stepped down from the board, wanting to spend time on his own songwriting career. Don McGlashan was voted by the membership to be the new writer-director. Freed of being the go-to person for every songwriter’s problems, Baysting instead focused on writing more songs, and writing children’s books, including The Underwatermelon Man with Fane Flaws and Peter Dasent. Throughout this period he collaborated with many other songwriters, spreading the message that writing for children is fun. He also signed his music publishing to Origin Music Australia.

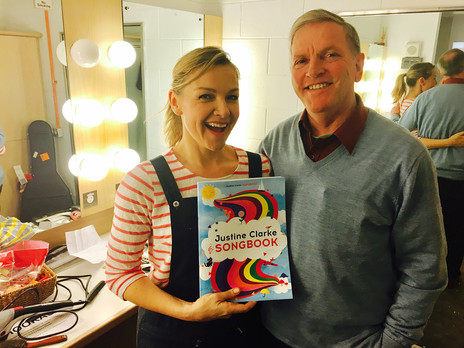

Baysting’s career has had unexpected good fortune writing songs for Australia’s under fives: the Play School crowd. In 2000, when Peter Dasent became music director of ABC’s Play School, he enlisted Baysting’s help as a lyricist. They began writing little songs for Play School’s key audience. When Justine Clarke, Play School’s biggest star, heard some of Dasent and Baysting’s songs, they began to be included in the show. The trio is now a small industry, with platinum, gold and silver selling records, ARIA awards, and widespread recognition for Clarke. She has become a national institution and one of the ABC’s star attractions. Their biggest hit ‘Watermelon’ – with over 2.5 million views on YouTube – is a tribute to fresh fruit. Many of the songs have become standards in Australian homes and classrooms.

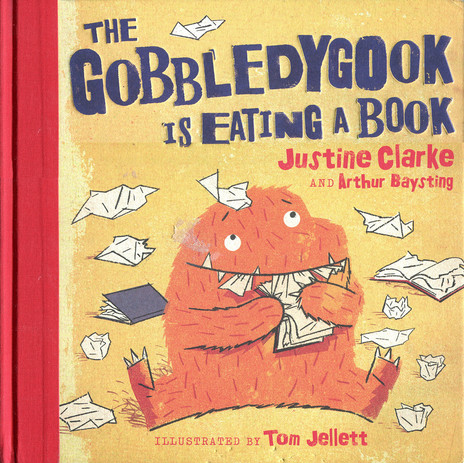

Baysting and Clarke have also written two successful children’s books, with illustrations by Tom Jellett: The Gobbledygook is Eating a Book (Penguin/Viking, 2012) and The Gobbledygook and the Scribbledynoodle (2016). “The Gobb” has now been translated into French, Chinese and Korean.

Baysting is still working on children’s rights. He assisted Suzy Cato and Apra in establishing the Kiwi Kids Music Trust, which brought together New Zealand’s writers of children’s music. From a handful of members three years ago, the trust now boasts more than 140 active children’s songwriters and performers, releasing songs, doing live performances and beginning to be seen on television. Major support for the group comes from school teachers all over the country, many of whom meet up every November at the NZ Ukulele Festival in Auckland. When Baysting sees the grandstand fill with over 2000 school children, all singing New Zealand songs, he is a happy man – he knows good things are happening.

When Baysting hears over 2000 school children, all singing New Zealand songs, he is a happy man.

Baysting looks back on a career in which New Zealand music was regulated by gatekeepers and weighed down by official obstacles. “New digital media has changed all that,” he says. “Traditional broadcasting is becoming redundant and the new digital world means songwriters can get their music to children all over the world. The success of a song like Craig Smith’s ‘The Wonky Donkey’ shows what can be done.” (Baysting and Smith are writing a theatrical version of The Wonky Donkey.)

“I believe that anyone can have fun and success writing songs,” says Baysting. “I think all parents should sing to their children and songwriting should be taught in schools – my friend Mike Chunn helped make that happen. We need better education for our children, especially the under-fives, and creating our own music is a vital part of that. There are now established organisations to support kids’ music, such as the Ukulele Festival Trust, Menza (the Music Education Aotearoa Trust), Mike Chunn’s Play It Strange, the Kiwi Kids Music Trust and many councils around the country. I think Aotearoa has some of the best songwriters in the world and our children’s music is taking off. I especially admire Apra and Suzy Cato’s Kiwi Kids Music songwriters, who are giving children what they really need – that is their own culture.” (On 21 November 2019, Apra NZ announced a new annual award for those who have championed children through the creative arts, education, or advocacy: The Baysting Prize.)

Baysting himself still writes every week, sometimes a sweet love song with Bill Lake, otherwise a song with Peter Dasent for Justine Clarke or Suzy Cato, or something new out of the blue.

--

Arthur Baysting passed away on 3 December 2019, writing songs and making plans to the end.

--

Dreams, Schemes and Themes: friends and collaborators share their encounters with Arthur Baysting.

Part 1: 1968-1977 – Nelson, Showtime Spectacular, the Listener, Elam, The Young New Zealand Poets, Red Mole and Neville Purvis, Sleeping Dogs.

Part 2: 1978-2019 – Rough Justice, Windy City Strugglers, The Crocodiles, Apra, NZ Music Commission, children’s songwriting, Pasifika.

Read: Arthur Baysting on Kiwi Night, Sydney, 1984

Read: Song lines – Arthur Baysting on songs about New Zealand.