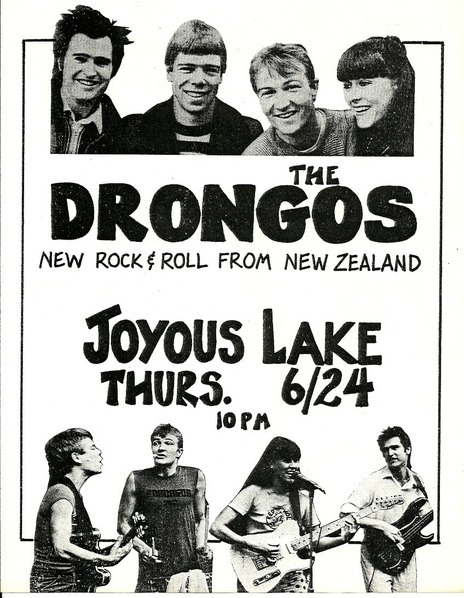

The Drongos all came from Wellington, where, as Red Alert, they were the backing band of the theatrical troupe Red Mole.

The Drongos originated from Wellington, where, as Red Alert, they were the backing band of the theatrical troupe Red Mole. Shortly after recording the live album Crossing the Tracks live at the Maidment, both Red Mole and Red Alert left for the USA. By this stage Red Alert were Richard Kennedy on guitar and vocals, Jan Preston on keyboards, Jean McAllister on guitar and vocals, Tony McMaster on bass and Stanley John Mitchell on drums.

While Red Mole headed to New York, for Red Alert the first stop was San Francisco, which still seemed like it was in the fag-end of the 1960s, with people walking the streets looking like characters in The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. There was also a heavier undercurrent of post-60s trauma and psycho-babble. The week they arrived the “Jonestown massacre” took place: 909 members of the San Francisco-based cult the People’s Temple died in a group suicide at their farm in Guyana.

After eight months gigging alongside bands that featured scrambled leftovers from the Summer of Love, Red Alert got the call to join Red Mole in New York. They drove across America in three days. Arriving in New York, it wasn’t quite how they pictured it. Compared to California, it looked old – the city was still recovering from its mid-70s depression. “I noticed how dowdy the people looked in the streets, especially in the theatre district,” McAllister told the NZ Listener in 1985. “I was thinking, is all New York like this? But you only have to go over a couple of blocks to Fifth Avenue and the women are dressed up to the nines; go down to the East Village and the punks are there in their regalia.”

Red Mole’s season at the Theater for the New City received great reviews, but lasted only the standard three weeks. It was reviewed in the Village Voice, which was quite a feat, but the troupe realised that they would never become the toast of the town, as they were in Wellington when they had people queuing down the street to see the cabaret at Carmen’s Balcony. Anything low budget in New York would always be a fringe attraction.

After the season finished, Preston and Kennedy travelled with Red Mole to England where they had work for about five months. The rest of the band sat in their hotel room, with no money, wondering what to do next. The answer came from the room next door. Rubin Levine was a violinist and comedian – and a veteran street performer. “It’s all out there, kids,” he said, “all ya gotta do is go get it.”

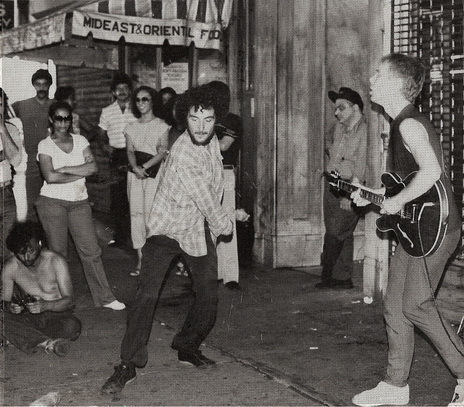

Mitchell had the least money of all, so he went out with his snare drum and played by himself. He came back with about $US70. “So the next day everyone went out,” recalled McAllister. “The first day we went out to Central Park and we were just terrified. We’d worked up these little harmonies in the hotel room and it sounded quite sweet, and the first day we were out there for two hours and we made $67.” (In 2014, that equates to $US230.)

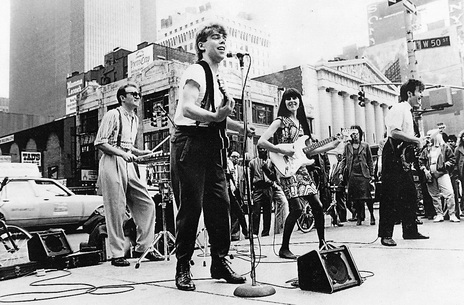

Once Kennedy returned from the UK, they called themselves The Drongos and developed a routine. They would leave their hotel and play the midtown district several times a day. They would catch the lunch hour crowd, then the five o’clock crowd going home from work. Then it was the pre-theatre crowd, and finally they’d play for the crowds that emerged during intermissions. “Everybody would be outside sipping their wine and smoking, then five minutes later another theatre would have their intermission, and we’d run across the road and play that,” said McAllister. “And these theatre people, they’d gone out for a night’s entertainment and they were really in a giving mood, and we were so sweet. We were! And they just handed over money. One night we made $100 in just 15 minutes.”

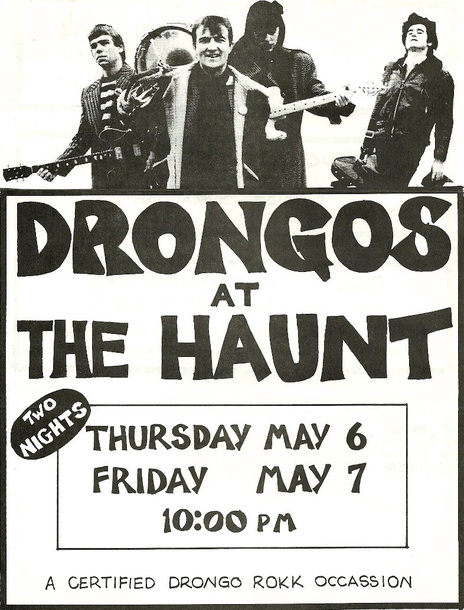

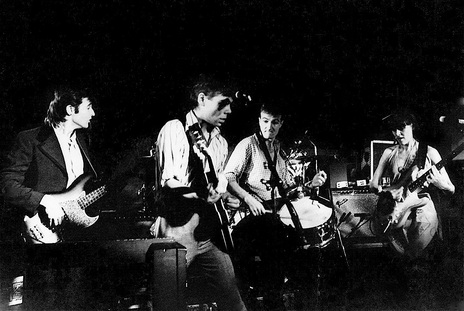

The Drongos broke through to the next level by appearing at the legendary CBGB club on audition night.

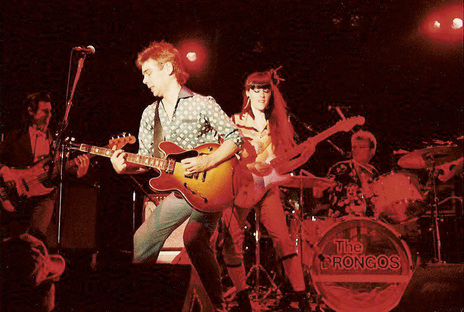

It was much better money than the band could get at New York’s hippest rock clubs. But The Drongos broke through to the next level by appearing at the legendary CBGB club on audition night. They were booked for the next Saturday night. “As far as the club scene goes, that happened very quickly,” recalled Kennedy. “We started playing the Ritz, but all the time kept the street thing going.”

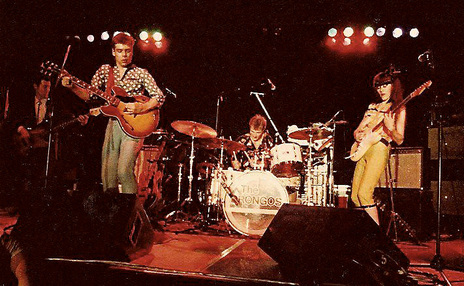

Soon, the bulk of The Drongos’ performances were at clubs and universities, using a PA, McAllister on keyboards and Mitchell playing a full drum kit. They would always include a “street set” in the middle of their act, with Mitchell stepping forward with his snare. “We’d do four or five songs, bang bang bang bang,” said Kennedy. “It always picked the show up.”

While in New York, many A&R reps from major labels showed interest – including the legendary John Hammond, who signed Dylan and Springsteen – but they never got their ink on a contract. Instead, they released two LPs on the indie label Proteus, which was primarily a publisher of music books. Their self-titled debut was produced by Steve Katz, formerly guitarist with Blood Sweat & Tears; it included the single ‘Don’t Touch Me’. Their follow-up, Small Miracles, was recorded on the streets of New York, with just a few sidewalk sessions and some bass overdubs needed to complete the recording (on the street, Mitchell didn’t use a bass drum). ‘Substance Abuser’, the single, was a mix of power-pop and the cartoon punk of The Ramones.

The album reached #4 on the playlist charts of the US college radio stations, and many enthusiastic reviews. While the Village Voice’s acerbic Robert Christgau dismissed them in a throw-out list of band names labelled “New Wave”, the equally respected Robert Palmer of the New York Times was more considered. In 1984 he wrote that The Drongos’ debut was “a delightful melange of funk rhythms, country harmonies, precisely layered electric guitar counterpoint and airy folk-rock sounds, with many influences, old and new, absorbed into a delightfully original sound.” The reviewers liked their authenticity, but the reviews didn’t translate to sales. “If we had $500 for every great review we got, we’d be retiring and living off the interest,” said Kennedy.

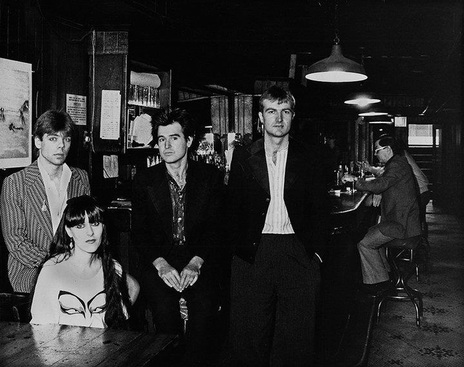

The Drongos’ New York attitude and initiative were apparent when they returned to New Zealand for several gigs in the summer of 1985-86. They arranged a local release of Small Miracles through WEA, and pre-arranged the venues and publicity. “Selling yourself can sound like a hard hustle, but when you’re playing on the street you’re selling yourself,” McAllister reflected in our 1985 interview. “I suppose we’ve been forced into this, that you have to sell yourself. Because to not sell yourself is to die.”

While in New Zealand, the quartet dropped into Parliament to visit their biggest fan, David Lange.

While in New Zealand, the quartet dropped into Parliament to visit their biggest fan, David Lange. He had met them while crashing on the New York couch of a mutual friend, the expatriate chanteuse Linn Lorkin. But The Drongos’ visit home wasn’t quite the working holiday it was billed at the time. Burnt out, the group had already made plans to split, and the visit was a way of showing their New Zealand friends and family what they had been up to.

These days, only Mitchell remains in New York, where he performs, records and produces music. McAllister and McMaster soon returned home to raise a family and become involved in the Auckland music scene. Kennedy moved to England, where he works as a solo guitarist. A left-hander who plays a right-hand instrument upside down, on The Drongos’ return to New Zealand in 1985 his show-stopping moment was a solo rendition of Peter Posa’s ‘White Rabbit’. He had first wowed Wellington audiences with it when playing for Midge Marsden’s Country Flyers as a teenager at the Royal Tiger, 10 years earlier.