By high school they had graduated to a cabaret band led by saxophone player Des Parks. “Des was about five foot two with really, really disconcerting blue eyes and red hair,” Marc Hunter would recall years later. “He had a sax down to his knees and he scratched his groin on stage all the time. I think Des had crabs for about 60 years, or maybe he was one of those short guys who have to draw attention to their crotches…”

Hamilton, Ngaruawahia and Dragon

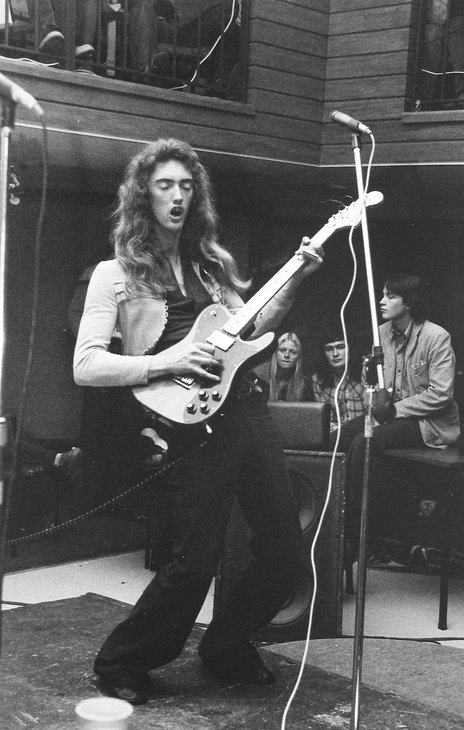

In 1970, having finished school, Todd moved to Hamilton to attend Teachers College, where he formed a succession of short-lived bands, including Zeek and Heavy Pork: British-influenced power trios in which he played guitar; and OK Dinghy, a more American, hippie-style group, for which he shifted to bass.

By 1972 Todd had moved to Auckland and was trying to reconcile his determination to make original music with the reality of surviving as a professional musician. He wound up playing in a nightclub band to punters who only wanted tunes they knew. They called themselves Staff, because that’s how they felt they were treated.

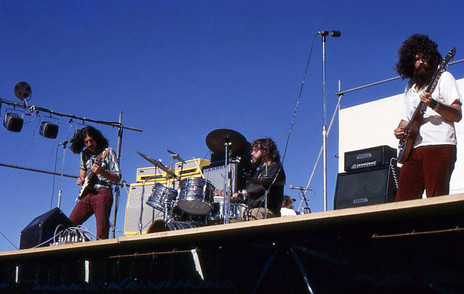

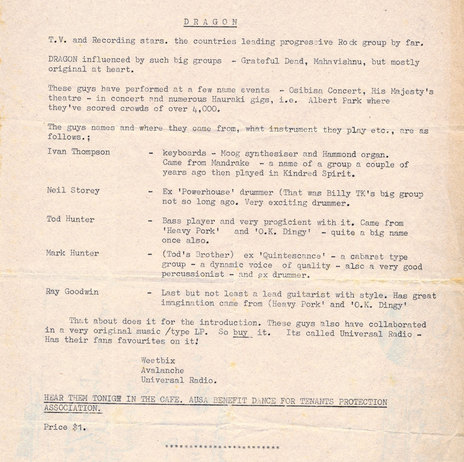

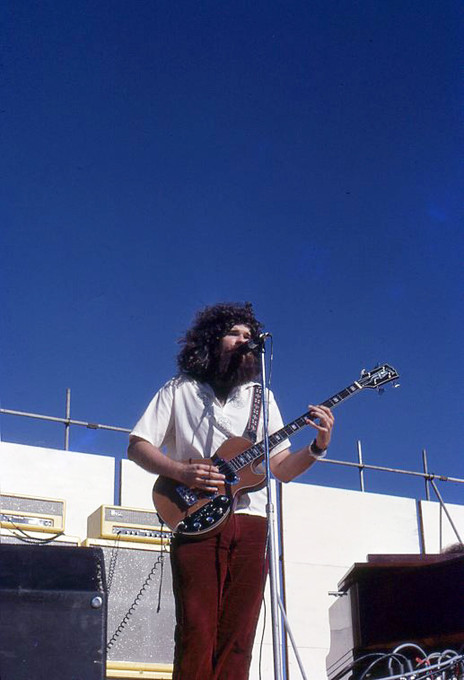

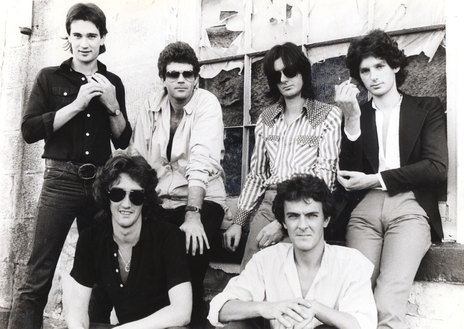

But with New Zealand’s first major outdoor music event on the horizon – The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival – Todd saw a chance to progress. With the current Staff line-up – Hunter, guitarist Ray Goodwin, drummer Neil Reynolds and singer/keyboardist Graeme Collins (formerly of Wellington pop act The Dedikation) – he worked up a set of originals, changed the group’s name to Dragon (Collins’ suggestion, inspired by a session with the I-Ching) and secured a slot in the January 1973 event, alongside Black Sabbath, Fairport Convention, and a virtually unknown Split Ends.

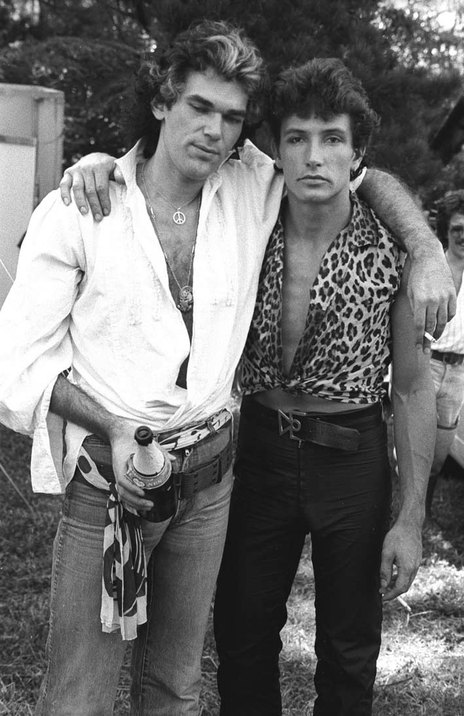

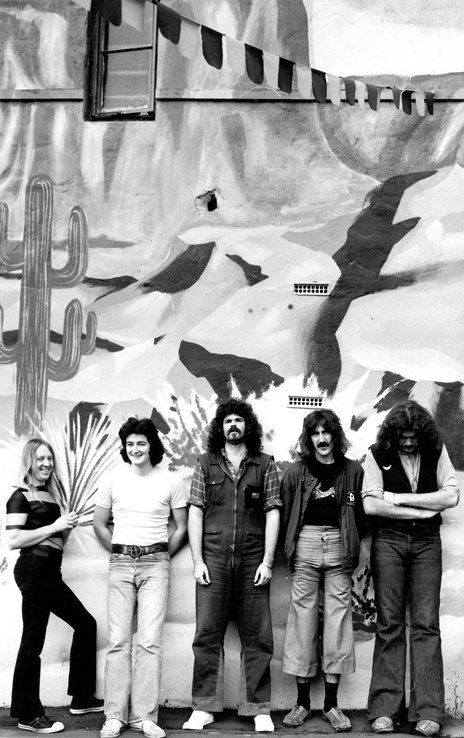

Though their Ngaruawahia performance went largely unnoticed, Dragon was born. By mid-73 drummer Neil Storey, formerly of Billy TK’s Powerhouse, had replaced Reynolds while Ivan Thompson had taken over Collins’ role on keyboards. And they had found a frontman: 19-year-old, 6’3” Marc Hunter.

Since leaving school, Marc had been drumming in cabaret bands, taking occasional turns as singer. ‘Misty’ was his showpiece.

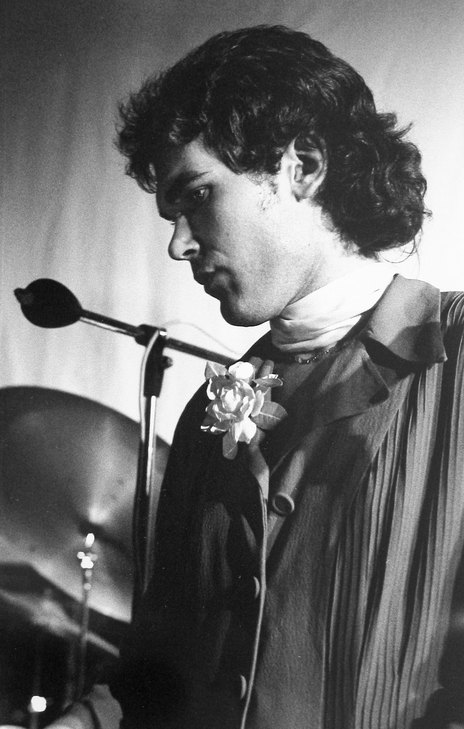

Since leaving school, Marc had been drumming in cabaret bands, taking occasional turns as singer. ‘Misty’ was his showpiece. The demands of fronting a rock band were somewhat different from crooning cabaret, yet the role proved ideally suited to his imposing stature, powerful voice, supreme self-confidence and mordant wit.

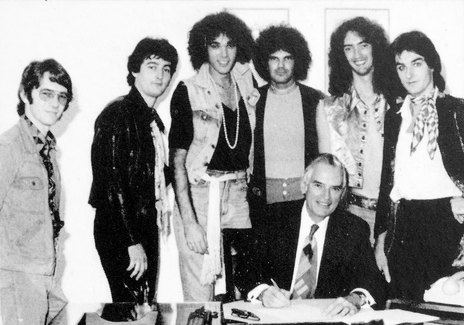

Universal Radio and Auckland

With this new-line-up, Dragon spent a year developing long original songs in a prog-rock vein, while maintaining just enough snappy covers in the live set to keep them employed in the Auckland nightclubs. By early 74 they had talked their way into a recording deal with Phonogram, whose head of A&R, Rick Shadwell, oversaw production of their first album. Cut at Stebbing Recording Studio in Auckland, Universal Radio was released in June 1974, one of just a handful of local rock albums to come out that year. It sold a respectable 4000 copies.

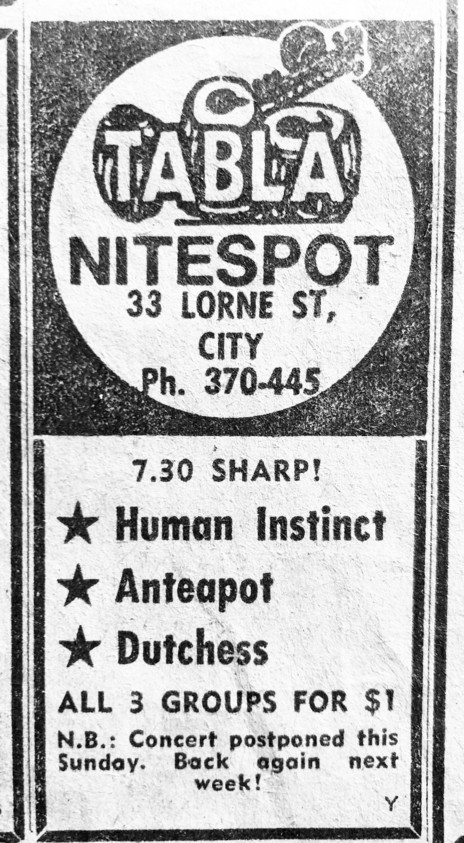

Though pitched somewhere between ponderous prog and effete folk-rock, the album at least set them apart from the mass of covers bands. This much was recognised by Wellington-based underground entrepreneur Graeme Nesbitt, who put them on tour around the country’s universities where original music was more likely to find favour. In addition they played concerts, such as the Buck A Head shows at His Majesty’s Theatre, which attracted students and similarly discerning listeners.

As the group grew in confidence, so did their theatrics. At some gigs they would don masks to portray the characters in their songs. During ‘Weetbix’, Universal Radio’s centrepiece, Marc would dramatically chop up boxes of Weetbix, spraying cereal all over the audience. And then there was the occasion, colourfully described in John Dix’s Stranded In Paradise, when they were joined onstage by a bald, stoned and pregnant stripper.

On the streets of Rock 'n' Roll Ponsonby

In late 74 they recorded a second album, Scented Gardens For The Blind. Though the title song was another opus in the vein of Universal Radio, there were hints of the rock and roll band they would become in more concise and punchy tracks like ‘Vermillion Cellars’ and ‘Grey Lynn Candy’.

The album (and its single, ‘Vermillion Cellars’, backed with the autobiographical ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Ponsonby’) was barely pressed before there was another line-up change: Ivan Thompson was out; instead of another keyboard player, they recruited guitarist Robert Taylor. In an autobiographical note penned by Taylor in 1977, he summarised his career so far:

“Born in Waipukarau, New Zealand… son of an ice cream manufacturer and housewife… rugby and blues licks with the Māoris… confirmed in the Anglican church… won a scholarship to Wellington Uni… majored in English… English lecturer dealt dope, ran a rock band: goodbye studies… joined acid-symphonic rock’n’roll band Mammal...”

Mammal had been a band of renegade intellectuals, whose musical palette stretched from Motown to acid rock. It was fronted by Rick Bryant, a blues-soul singer, university lecturer (and occasional pot seller), and managed by Nesbitt, Bryant’s flatmate and, for a time, cellmate. After Mammal’s breakup at the end of 74, Taylor joined Dragon, bringing with him a tougher, funkier sound.

In May 75, Dragon left for Sydney, where they were in for a shock.

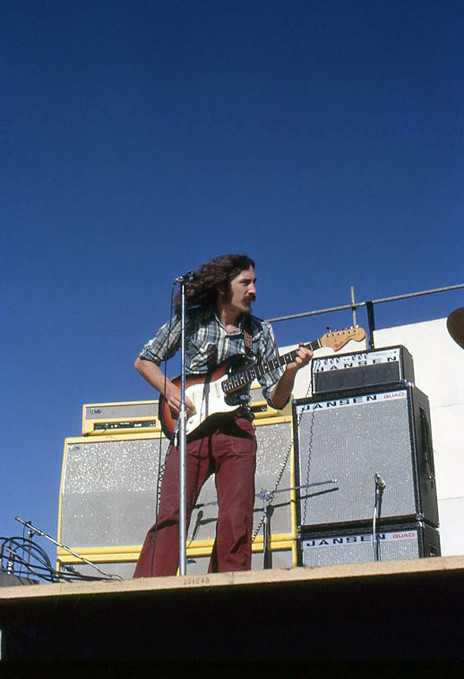

He also brought songs. It was ‘Education’, a Taylor original, which would be Dragon’s next single in early 75. Though it wasn’t a hit, you can hear in the track the way his addition has already shaken the last vestiges of prog-rock effeteness out of the group, replacing them with a funky swagger.

With Taylor on board, Dragon toured relentlessly. Yet after a few laps of the North and South Island it was plain that New Zealand offered nowhere further to go. In May 75, Dragon left for Sydney, where they were in for a shock.

Paul Hewson

With a repertoire that mixed eclectic originals with covers of Lou Reed, Little Feat and the odd jazz-rock instrumental, Dragon still hadn’t found the formula to win the Australian crowds. Money was scarce, living conditions squalid and employment prospects shaky. Enter Paul Hewson, a talented and promising songwriter from Auckland’s Blockhouse Bay, who the group had been courting since their Ponsonby days.

Hewson’s arrival coincided with the release of the Ray Goodwin-penned ‘Starkissed’, their first Australian single and last for Polygram. Though this glam-rock stomper got them their first Australian TV appearance, it failed to take off. Ray Goodwin left soon after.

It was not until 1976 that they recorded again, this time for CBS. Crucial in securing the new contract was the support of Peter Dawkins. A fellow New Zealander, Dawkins had produced a string of New Zealand number ones including Shane’s ‘St. Paul’ and The Fourmyula’s ‘Nature’, before taking his skills across the Tasman where he produced John Farnham, Billy Thorpe, Spectrum and many other big Aussie names. He had heard Dragon live and identified hit potential in their newer original material. Even so, CBS support was tenuous, particularly as the group’s first single for the new label – ‘Wait Until Tomorrow’, a Taylor song he had first recorded with Mammal, backed by Hewson’s ‘Show Danny Across The Water’ – made little impression on the charts.

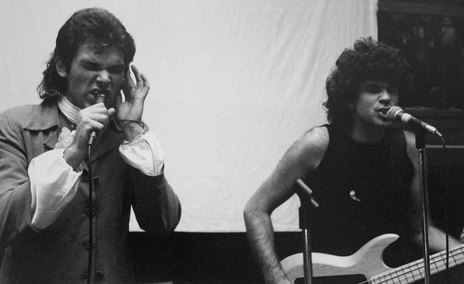

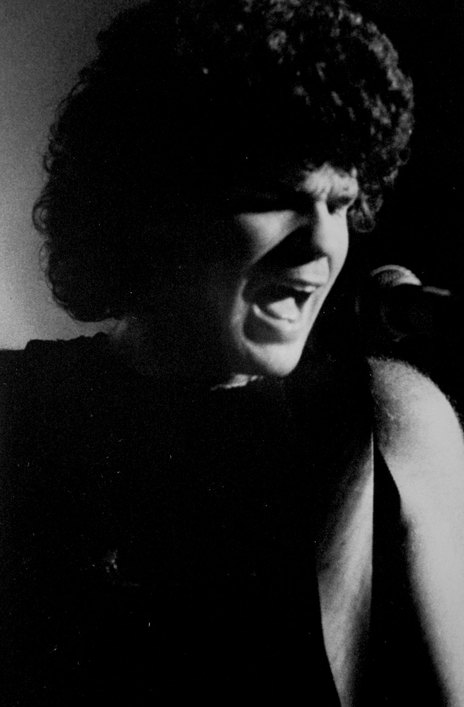

It was make-or-break time, and for the follow-up the group pulled out the stops. ‘This Time’ was credited to all five members of the group, but with particular input from Hewson. It became the prototype for the kind of pop anthem that would become Dragon’s signature over the next few years. Rhythmically direct with a four-on-the-floor beat and soaring chorus, in which Marc’s strong vocals were joined by full group harmonies, it was like a cry of defiance.

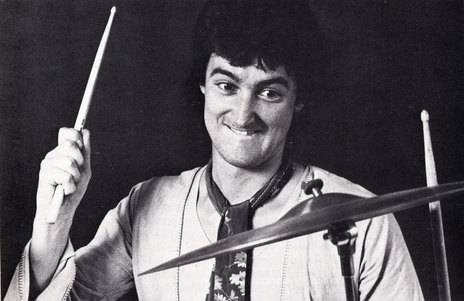

Just as the record began its ascent of the Australian charts, drummer Neill Storey was found dead of a drug overdose.

‘This Time’ was not a major hit, but big enough to increase the band’s stock with CBS. But the song’s tone of optimism seems bittersweet in the light of what happened next. Just as the record began its ascent of the Australian charts, drummer Neil Storey was found dead of a drug overdose, 22 years old.

Shell-shocked yet reluctant to let go of their hard-won rung on the Australian pop ladder, the band flew in a new drummer from New Zealand, 20-year-old Kerry Jacobson, with whom Taylor had previously played in Mammal.

Raw talent and recklessness

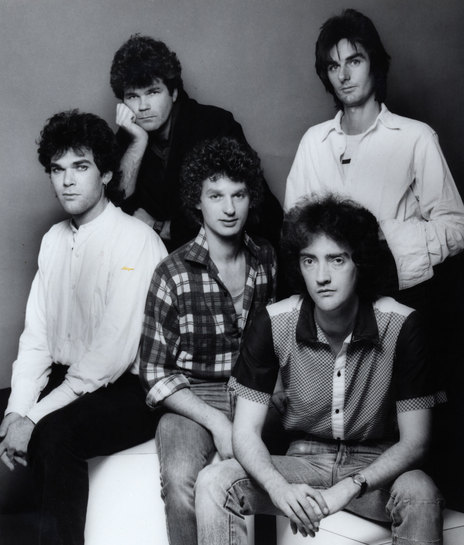

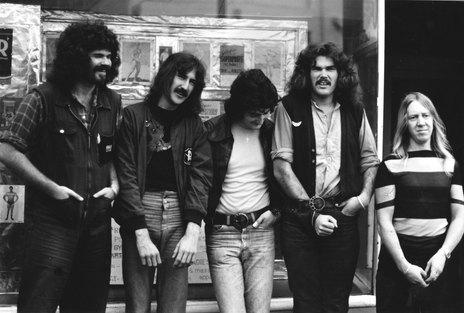

This was the line-up that, over the next two and half years, would establish Dragon’s legacy. It is a legacy won by a combination of hard work and hard play, raw talent and recklessness. In that time, the group would travel thousands upon thousands of miles across the Australian continent, playing hundreds of gigs, sustaining themselves on a variety of highs, legal and otherwise.

The endless touring turned them into an incredibly tight and supremely self-confident unit. Returning to New Zealand for a brief Nesbitt-promoted visit, they were lean, loud and mean, barely recognisable as the same band that had left a little over a year earlier.

‘Get That Jive’ was their next single, their first with Jacobson, and first to insinuate itself into the Top 20. Sunshine, their first Australian album, followed in mid-77, and contained both the recent hits plus a spread of material that showed the group’s depth and capabilities. Members of the group wrote in various combinations and sometimes on their own. The songs Taylor had a hand in such as ‘Blacktown Boogie’ and ‘Street Between Your Feet’ leaned towards funk. Hewson’s songs, such as the cautionary ‘Same Old Blues’ or the aching title track, were more melodic and melancholic.

There were also dark hints of the netherworld they now inhabited, in songs like ‘Mx’ – short for mandrax, the sedative known in the USA as Quaalude. Years later, Taylor would recall the friendly street girls who would leave a row of the pharmaceutical on top of the group’s amplifiers during the gig, to be consumed at the end of the night. Living and playing around Sydney’s notorious King’s Cross, the group’s circle included members of the Mr Asia drug ring.

The lifestyle was dangerous in other ways too. With all the miles they were travelling, accidents became almost inevitable. A pair of car crashes that year saw Taylor, Hewson and members of their road crew hospitalised.

‘April Sun’ was a massive Australasian hit, kept from No.1 in Australia only by Paul McCartney’s deathless ‘Mull Of Kintyre’.

Yet if these were dark portents, professionally things had never looked brighter. The idea for ‘April Sun In Cuba’ came from a book Chess enthusiast Hewson had been reading about the champion Bobby Fischer, in which he credited losing a game to being blinded by the Cuban sun. Taylor recalls Hewson knocking out its catchy two-chord, rhumba-style riff on a broken guitar with only three functioning strings. With Marc Hunter contributing to verses that referenced Castro, John F. Kennedy and the 1961 Missile Crisis, ‘April Sun’ was a massive Australasian hit, kept from No.1 in Australia only by Paul McCartney’s deathless ‘Mull Of Kintyre’.

The hit was promptly followed by a second Australian album, Running Free, which included the Hewson-penned singles ‘April Sun In Cuba’, ‘Konkaroo’ and ‘Shooting Stars’ along with streamlined rockers (Marc Hunter’s ominous ‘Mr Thunder’, Taylor’s seedy ‘Bob’s Budgie Boogie’) and the occasional downbeat tune from Hewson (the prescient ‘Shooting Stars’ and bravura ballad ‘Since You Changed Your Mind’, which took Marc Hunter back to his cabaret roots.

Dragon’s records were getting plenty of airplay and sales, in both Australia and New Zealand. Their Australian fame was hugely boosted by their regular appearances on television, notably the nationally screened ABC television show Countdown.

Burn Down The Bridges

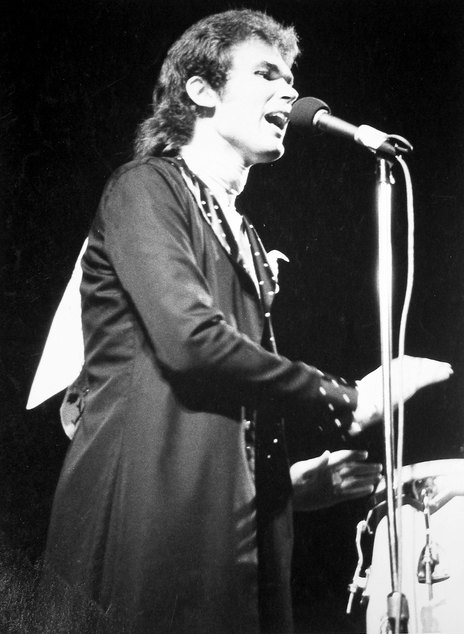

As their stardom soared, a dichotomy became more pronounced. On TV and radio Dragon were pop darlings, but on the road they were rock and roll animals. Young punters coming to shows to hear their favourites were scandalised by a show that could have had an X-rating.

A centrepiece of the live set was ‘Miss Mercy’, a song so offensive they never dared record it. A graphic tale of rape and murder, it made the Stones’ ‘Midnight Rambler’ sound like a nursery rhyme, and Marc Hunter would enact in graphic detail, sometimes dragging audience members onstage to participate in the mime.

A January 1978 visit to New Zealand saw them headlining the Great Western Music Festival, Marc Hunter rhapsodising about how nice it was to be back “among the pongas and the pines”, dedicating a song “to the Crewe murders” and guzzling champagne from the bottle before the 7,000-plus crowd.

Back in Oz, the near-constant touring stopped only long enough to record another album, O Zambezi, which produced further hits ‘Still In Love With You’ and ‘Are You Old Enough?’ – the latter finally giving them their elusive Australian No.1.

Australasia conquered, America was the next frontier. Dragon had been signed to the USA-based Portrait label, a boutique offshoot of CBS. For their Stateside launch the group were sent to Texas to open shows for albino blues-rocker Johnny Winter. Winter’s blues-boogieing, beer-swilling, and possibly pistol-packin’ punters were intuitively suspicious of these smartass Antipodean pop stars, with their song about Cuba and their arrogant frontman. Suspicion turned to outright hostility when Hunter began taunting them, asking one audience if it were true that oral sex was illegal in Texas.

As Hunter chided both crowd and crew, speculating on their sexual preferences, the Texan roadies were overheard taking bets as to how long it would be before someone shot him.

The nadir was reached at a show in Austin, where Hunter got into a row with stage crew who had mistaken his gesture for more level in his monitors as an insult. Words were hurled, then a bucket of ice thrown at him, followed by bottles, glasses and other projectiles, from both stage-side and front of house. As Hunter chided both crowd and crew, speculating on their sexual preferences, the Texan roadies were overheard taking bets as to how long it would be before someone shot him. While the rest of the band retreated in fear of their lives, Hunter – still centre-stage – adopted a crucifixion pose.

“Well I think that went okay,” his brother remembers him saying when he finally joined the others in the dressing room. In fact it could not have gone any worse. Dragon limped back to Australia, strung out, defeated and in disarray. By the beginning of 1979 Marc Hunter had been fired, for his own sake as much as anyone’s.

New Machine

Recruiting sax player Billy Rogers and vocalist/violinist Richard Lee, Dragon continued for a year and cut a further album Power Play, shifting away from pop towards a more virtuosic rock. But the hits stopped dead, and by 1980 the band had dissolved.

However, debts remained from the wild years and so in 1982 Dragon reformed, complete with a rehabilitated Marc Hunter, initially for a one-off, coffer-replenishing tour. So successful was the reunion – with capacity crowds singing along to the five-year-old hits – they decided to continue. A 1983 single ‘Rain’, composed by Marc, Todd and Todd’s partner Johanna Pigott, gave Dragon a brand new hit; it was followed by another successful single, ‘Magic’, and album, Body And The Beat.

The new recordings were produced by Alan Mansfield, an American multi-instrumentalist who had previously worked with Robert Palmer and Bette Midler, and brought an 80s sheen to the traditional Dragon pop sound.

In 1983, Kerry Jacobson – still prone to the excesses of their late-70s heyday – left the group “for health reasons”, to be replaced by former XTC drummer Terry Chambers. Robert Taylor and Paul Hewson left not long after, Hewson returning to New Zealand where he died of a drug overdose in early 1985.

With only the Hunter brothers remaining from the original hitmakers, the group began to operate something of a revolving door, through which Australian guitarist Tommy Emmanuel and American drummer Doane Perry came and went. Both played on the Todd Rundgren-produced 1986 album Dreams Of Ordinary Men.

By now Dragon was becoming more a brand than a band. The Dragon sound was a trademark that could seemingly be stamped on anything the Hunters touched, even a 1987 cover of Kool and the Gang’s ‘Celebration’.

Yet another line-up (with New Zealand drummer Barton Price) cut the Bondi Road album in 1989, with its signature single ‘Young Years’ – written by Alan Mansfield and his partner, former New Zealand hitmaker Sharon O’Neill – again invoking the classic Dragon sound. Dragon continued with a core of Mansfield and the Hunters until 1995, when Todd retired from the band. In 1997 the group disbanded once more, after Marc was diagnosed with oesophageal cancer.

Incarnations

After Marc’s death in July 1998, it would be almost a decade before Todd Hunter would play any Dragon material. “It was never going to happen again. It was like some lurid airport novel that I’d read once,” he says.

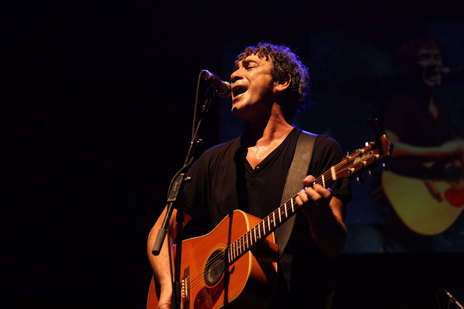

Instead, he turned his attention to composing soundtracks for Australian television. But in 2006, he started rehearsing a new Dragon line-up, featuring former New Zealand pop star Mark Williams in Marc Hunter’s old role.

“You get in a room, you start playing the songs … I could actually feel the goddamn Dragon lift itself out of the primeval mud.”

Taking to the road with “a bunch of songs that just about play themselves,” Hunter realised that “they are not our songs anymore. The songs belong to everyone.”

Yet in playing the old hits – the audience taking over much of the singing – the old Dragon seemed to all but become flesh once more. “Without getting too metaphysical, it’s like Paul and Marc are there. And they were such sardonic bastards, so cynical about everything, you just see them up in the back going ’Aw, you fucking idiots’.”

A late 2013 Acoustic Church Tour of New Zealand was a huge success and proved that Dragon, some 40 years since their debut, retained that same magic and pulling power.