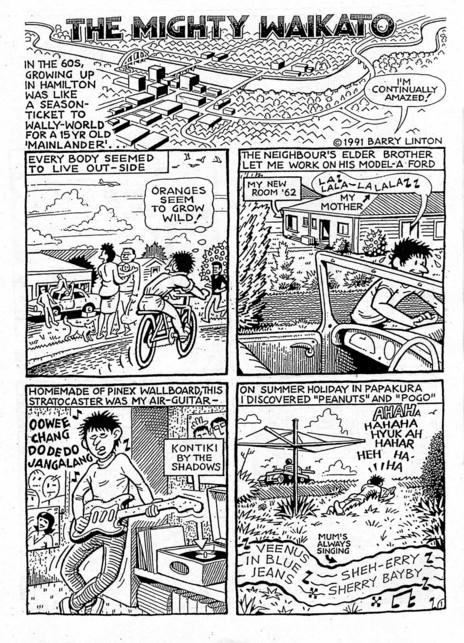

When he was growing up in Christchurch and Hamilton, Linton’s future was a struggle between art and music. He was the kid who drew pictures and even at primary school other children were coming to him for illustrations. But music was always there. “My world exploded when I discovered the Beatles,” he remembers. “For a long time I was undecided about whether I wanted to do music or art.”

“For a long time I was undecided about whether I wanted to do music or art”

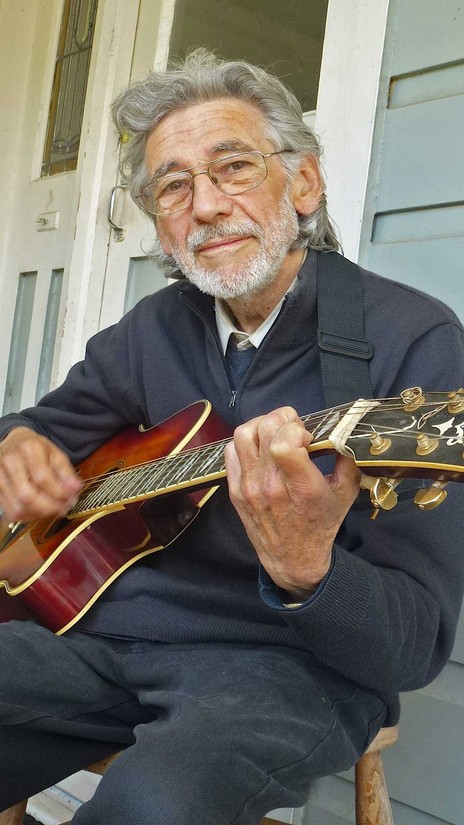

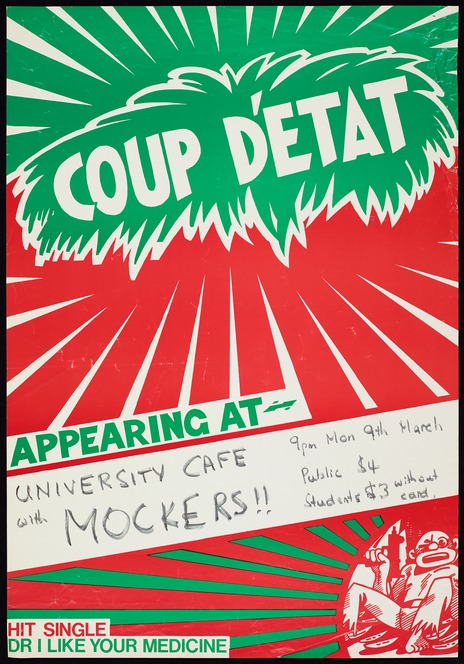

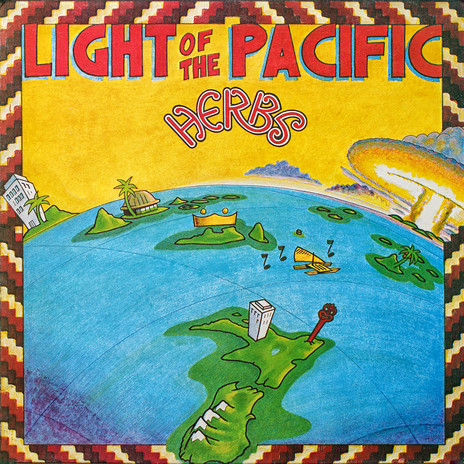

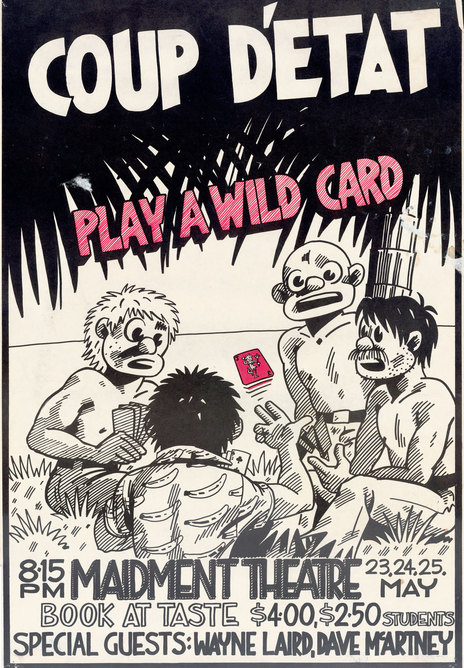

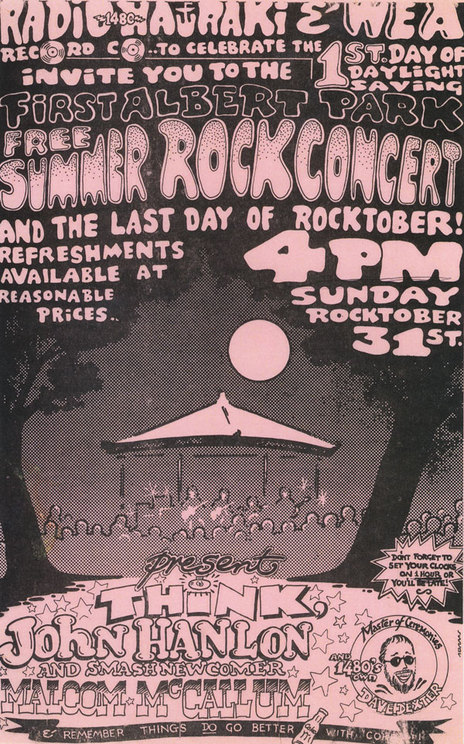

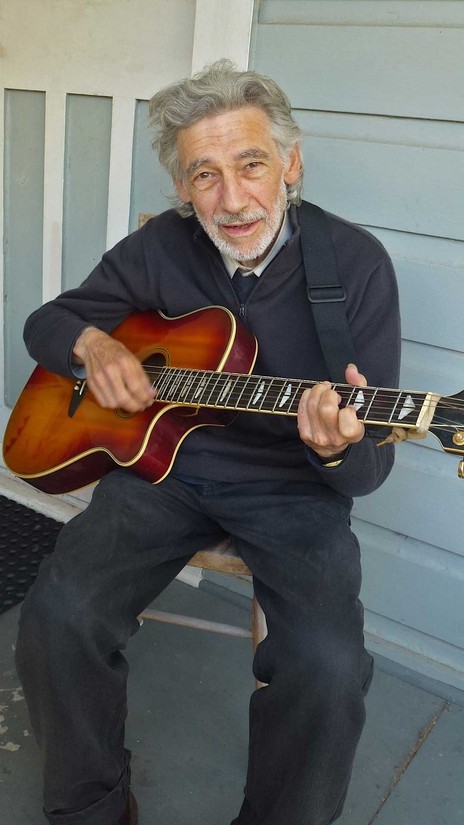

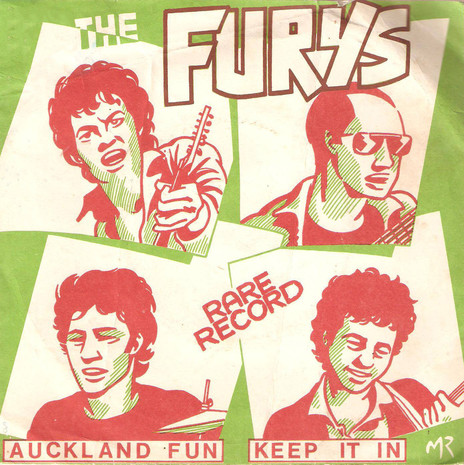

As it turned out, he did both. He’s never stopped playing guitar and in a career lasting over 40 years he’s done band flyers, posters, T-shirt logos, record covers, backdrops for live bands and illustrated his own record reviews.

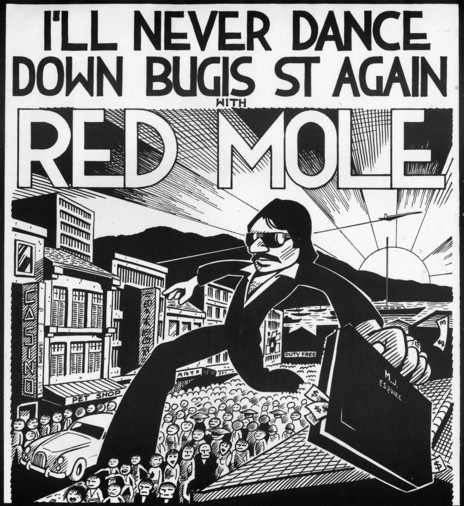

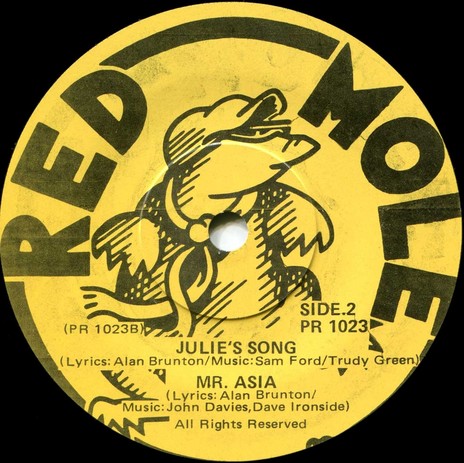

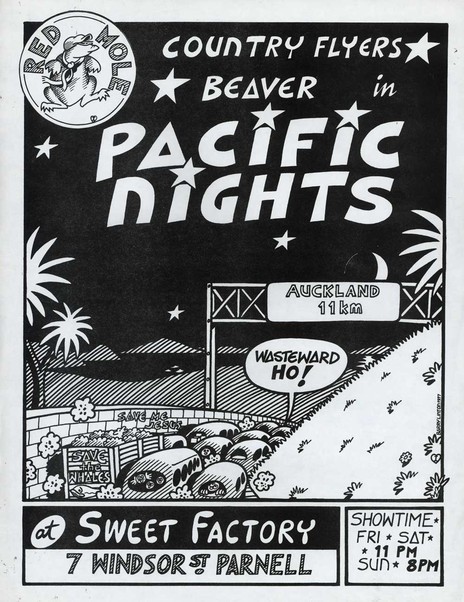

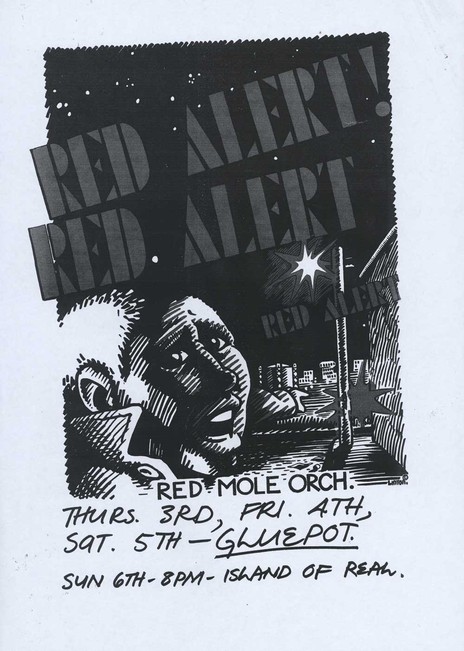

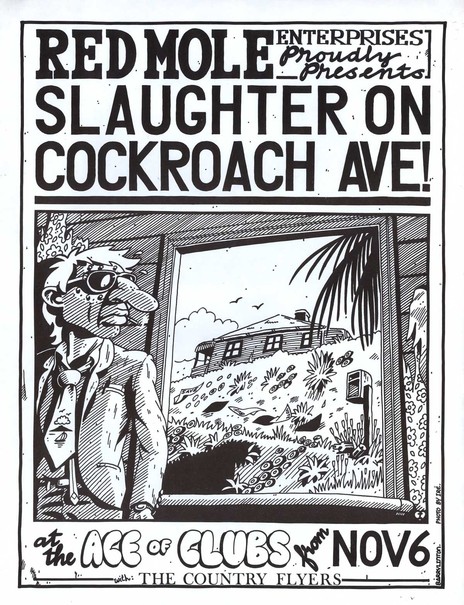

One association he remembers fondly was working with Alan Brunton from the alternative theatre and music group Red Mole. When they moved to Auckland from Wellington’s Carmen’s Balcony in 1977, Brunton saw Linton in his “Pacific Nights” T-shirt and borrowed the title for one of their shows.

It sparked a long association between the two: Linton joined the group as stagehand and designer and became their official artist. He did their posters for shows including Slaughter on Cockroach Avenue, Goin’ to Djibouti, Just Them Walking and The Book of Life. He designed their logo and his Mole image became emblematic for the group’s subsequent international travels.

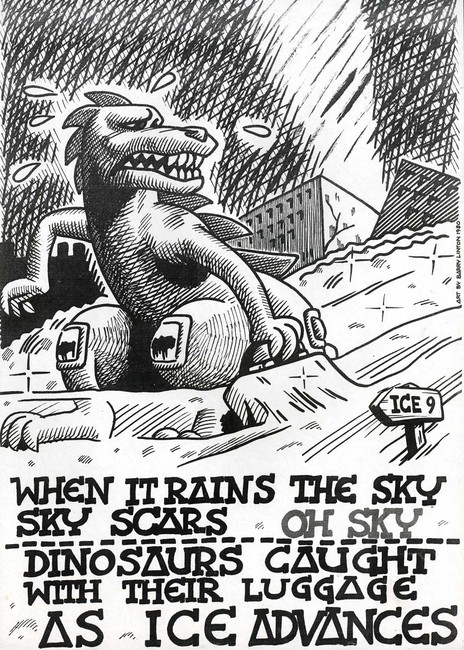

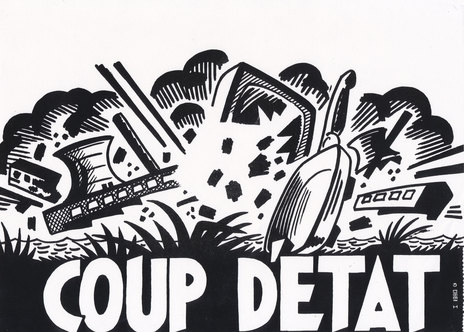

The live band for Red Mole’s Auckland shows was The Country Flyers and this paid off a few years later when lead singer Midge Marsden asked Linton and Pete Adams to make a backdrop for the Burning Rain tour.

They found a huge roll of canvas, laid it out on a neighbour’s driveway and drew up the picture of destroyed buildings with balls of fire hurtling down from the sky. It’s a picture that has become familiar from images playing on our evening television news.

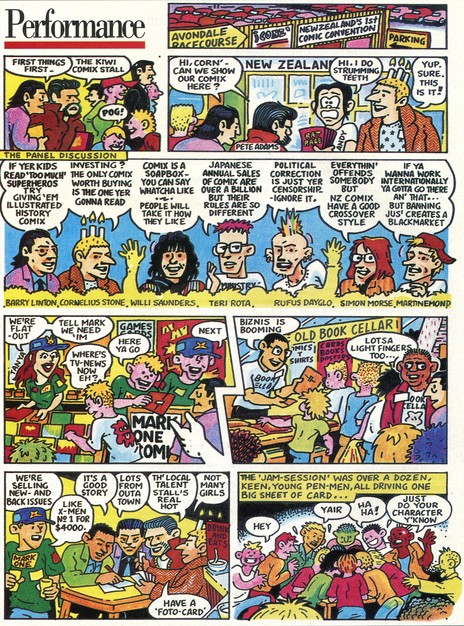

Regarded as a godfather of the New Zealand comix scene, Linton has been praised by younger artists. Dylan Horrocks, Tim Bollinger and sometime flatmate Cornelius Stone are among those who cite him as an influence. Now, with a flurry of recent publications, he is getting some of the recognition he deserves.

A cheerful, modest character who spends much of his time working in his studio/ bedroom, Linton takes it with a grain of salt. “I’ve been called a legend but it doesn’t mean anything,” he laughs. “I certainly don’t get legendary pay. I keep doing it and I’m happy when people like my work.”

Melbourne’s Pikitia Press, run by expat Matt Emery, has just published Aki in Tiko, the second of Linton’s stories about the epic voyages of a stone-age sailor. Pikitia is also publishing Conversations with Barry Linton, a 36-page illustrated interview with Linton about his work.

Best of all, Chok Chok!, a new extended version of his collected work, is due out in 2016. The first edition, self-published by Linton in 1994, is now a collector’s item and Emery is excited about the new compendium. “Barry’s original publication was pretty modest,” he explains. “The new edition will have everything from the original plus more Strips, music posters and as much work from that era as we can fit in ... it’ll be a lot thicker than the original Chok Chok! so it’s a special collection.”

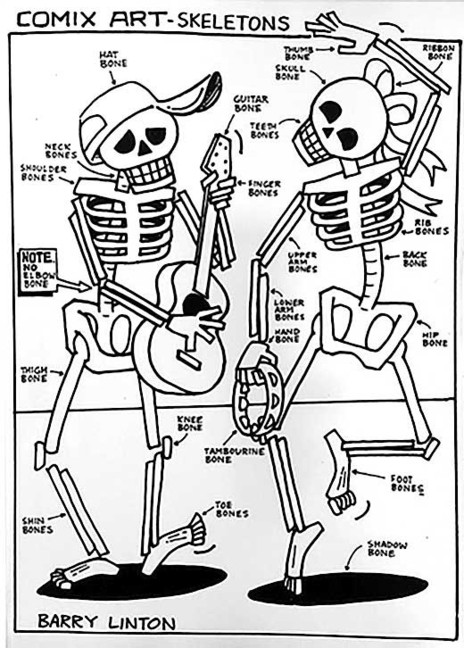

Barry’s personality is reflected in his comix, notable for their lack of aggro and violence. “I just like sunny images,” he told Tim Bollinger, “rather than the rain and the pain of the drama-rama.”

Emery can see it clearly: “There’s an innocence and a sweetness in a lot of his work. His comix explore landscape and talk about ideas and this is in stark contrast to a lot of the things going on these days.”

When he started out Linton had trouble coming up with characters. American comix artists created figures with intense psychological problems but ... “I came from a loving family and grew up in a reasonably happy home. I didn’t have that conflict to draw on.”

It’s true that his early life growing up in Christchurch and Hamilton was not very dramatic. He had a mother who bought him comics and a Navy father who gave him a passion for drawing ships and maps. But there was personal conflict. After scraping through school certificate he worked in a shoe shop and when they suggested he do their management trainee programme Linton had a life-changing epiphany. “I suddenly thought: ‘This is the end of the world. I’m selling shoes in Hannah’s in Hamilton and they want to make me a manager!’”

He hitchhiked to Auckland and went to Elam art school. He passed the practical but couldn’t focus on the art history papers. The main problem was music. “Jimi Hendrix came out, The Doors came out ... all these psychedelic bands. It was unbelievable.”

His early graphic inspiration came from the likes of Frank Bellamy in The Eagle and Harvey Kurtzman in MAD magazine, but by this time US underground comix like Zap and Bijou were available. Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton and Vaughan Bode utilised themes of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll and were a far cry from the comics of his youth. “They reminded me what it was I wanted to do because these guys were having so much fun!”

Linton was soon sending simple three or four panel cartoons to the Auckland University paper Craccum. They were whimsical, philosophical, sometimes psychedelic and the paper published everything he gave them. He was still hanging out with his painting mates at Elam until the Dean called him in to his office and pointed out that he hadn’t paid his fees and he was “distracting the other students”.

He was broke and faced a simple choice: he could get a paying job at the freezing works or follow the call of the open road. At the time he was dressing like Bob Dylan. As he later told Tim Bollinger, “I was Dylan in his Highway 61 outfit: floral shirt, dark jacket and Beatle boots ... tight jeans and big messy hair.”

Armed with his guitar and a copy of Walt Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass’, he embarked on a hitchhiking trip around New Zealand.

The decision was made. Armed with his guitar and a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, he embarked on a hitchhiking trip around New Zealand. Stop-offs on the “Hippie Highway” included Kaitaia, Whangarei, Whitianga, Wanganui, Wellington, Blackball, Christchurch, Dunsandal and, briefly, Dunedin.

In retrospect the experience was a key foundation for his comix career. At a student flat in Dunedin he liberated a book from their library and Eric Hiscock’s classic primer Cruising Under Sail became a talismanic text for him. Linton says the book tells “Everything you needed to know about sailing the Pacific ... In a way this was what led me to the Aki stories.”

Another stopover in his odyssey was in Wellington, on his way back north. It was there he first met comix artist Joe Wylie. With excellent drawing skills and shared interests in music and cartooning the two hit it off and later flatted together in Auckland.

Each has fond memories of many nights sitting drawing at the kitchen table. “It was a bit like a competition,” says Linton. “I remember Joe’s technique was really professional. He would pencil in the image, colour it with gouache and finish it off with ink outlines. I’ve still got some of his spaceship drawings in my scrapbooks.”

For Linton, 1977 was the year of the Sex Pistols, reggae and Spud Takes Root. Somehow it was the energy of that music that gave him the impetus to create his first real character. Spud was a skinny little punk kid with a cue-ball head who became the star of his first stand-alone comic. Self-published and printed on a photocopy machine, Spud marked the beginning of a stellar career.

He has always needed other jobs to give him space for his art. In the 1980s, during the Auckland property boom, he was on building sites. It was tough work, often using pneumatic tools and he used to come home at night, sit on his amp and hammer away on the guitar for therapy.

There were other jobs; cleaning offices and washing dishes in restaurants, but then he worked for Warner in their record warehouse. Here he met comix fan Terence Hogan who introduced him to his flatmate Colin Wilson. Linton recalls, “Wilson was starting up a new comic and because I’d done Spud Takes Root I was confident enough to give him stuff for his first issue.”

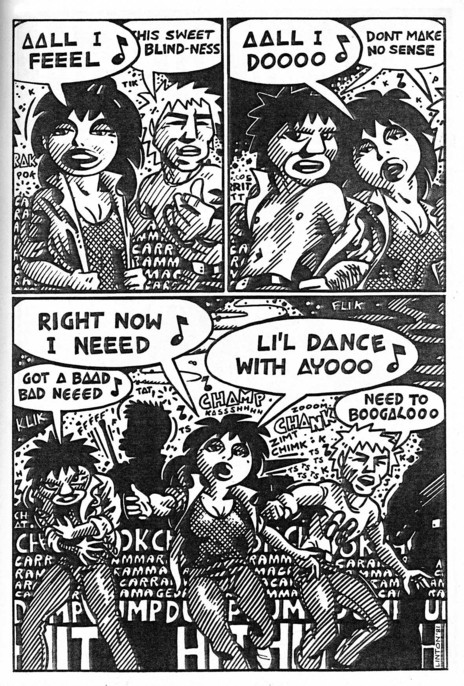

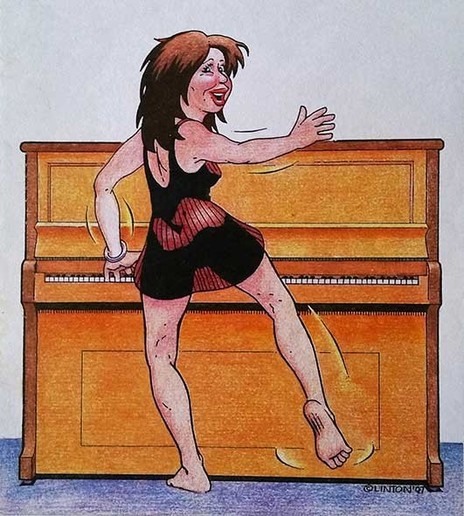

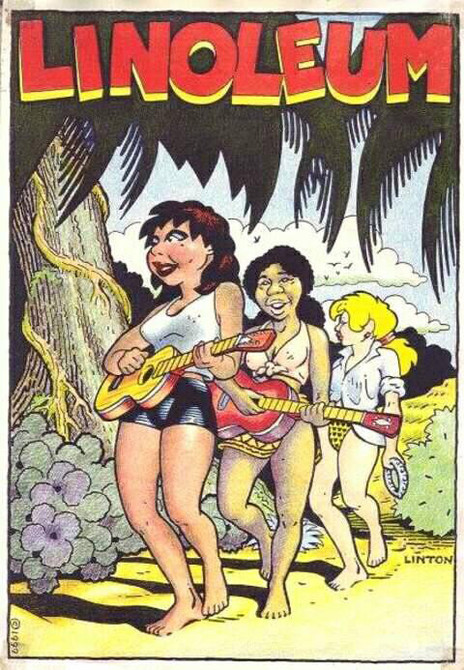

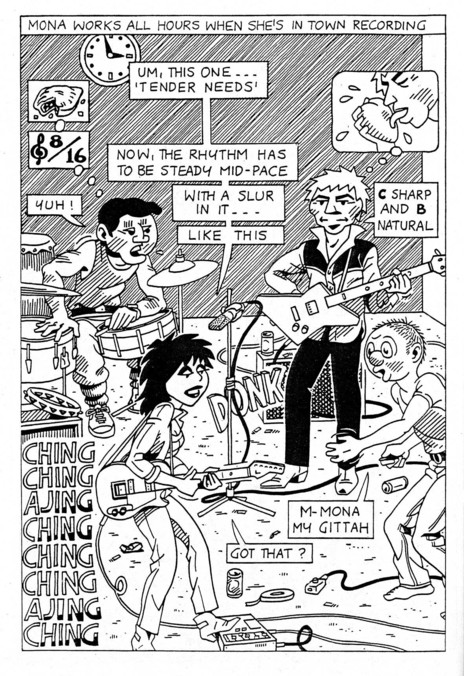

Strips marked a turning point in New Zealand comix history. Linton’s work presented an appealing Pacific world of strong women, dreadlocks and sexual freedom (these being the days after the pill and before AIDS). Auckland was often “Rockland” and the stories were infused with reggae music, sometimes with lyrics winding their way though the panels. During the 10-year life of Strips he drew over 100 pages and was in almost every issue.

As his name got around he started getting graphic work that paid actual money. He illustrated the Vet column in the NZ Women’s Weekly, drew for Dave Barry’s satirical pieces in the NZ Herald and worked for five years at the Auckland Star. His love of maps and graphs served him well for illustrations for business features and news stories.

In early 1991 the Star closed down but later there was a regular gig for OnFilm magazine and numerous freelance assignments. One of his favourite commissions was designing four large full-colour murals that became billboards in Waitakere City.

Over the years his tools and his process haven’t really changed. His favourite paper is Zeta which is hard and thin enough to trace through and gouache without buckling.” He uses Staedtler pens, (size 2 and 8) and his pencil of choice is a mars-metro (0.5-HB).

“I do very thorough roughs, first of all with pencil and then on laser copies with colour pencil and felt tips. After that I do the inking so it’s the third or fourth time I’ve done it. It’s painstaking work but it gives me the result I want.”

Linton is a meticulous archivist of his own work and the variety of styles and subjects much of it unpublished – is remarkable. There are portraits, political cartoons, urban landscapes, space vehicles, spirits, aliens, Rastas, musicians and sexy female figures. Many of the latter were inspired by a workmate he was secretly in love with. “We were friends,” he says, “but eventually she left the job and went to England.”

‘My Ten Guitars’ IS Linton’s comic-strip homage to the guitars he loved and lost.

One current project, My Ten Guitars, is a small homage to guitars he has owned (editor’s note: it was published posthumously). One of his favourites was a Jansen, a New Zealand-made copy of a Fender Telecaster, cherry-red with white piping. It was stolen from his flat but then he found an old scratched up Marinucci on a street stall that he bought for next to nothing. “It was covered with a thick layer of glitter and I scraped all the stuff off and it became my favourite grungy jamming guitar.” His current instrument is a Yamaha sunburst acoustic/electric.

He still listens to classic reggae but he has discovered world music, particularly Portuguese fado and, more recently, music from the Cape Verde Islands. “It’s very peaceful, very graceful and groovy ... if you listen to someone like Cesária Évora you can feel the swell of the deep ocean in that music.”

These days he’s working on the fourth Aki story and enjoys doing band posters and T-shirt designs. He misses having a regular income but appreciates the revival of interest in his work.

He is intrigued by the idea of an institution establishing a New Zealand comix archive: he worldwide explosion in comix and graphic novels and the number of New Zealand artists gaining international recognition suggests that some kind of home for local comix might be overdue. It’s a concept Pikitia’s Matt Emery is actively promoting. As one of his friends observes: “It’s no good storing important work in cardboard cartons under the bed; the silverfish are probably already in there.”

Meanwhile Linton’s fans are awaiting his latest work. It’s a new departure that reflects his interest in extra-terrestrial intelligence. Galacticians, published by Faction Comix, has full colour artwork and expresses his optimism for the future. Publisher Damon Keen says Galacticians features “Barry’s immaculate penmanship in an intergalactic stream of consciousness prose poem about the future.”

Linton admits that “The idea of ET contact makes some people roll their eyes. But even if it’s not true it’s a good mental exercise in what might be possible in solving the problems of civilisation.”

He likes drawing about the future and the distant past but finds today’s world more difficult. “It’s too foreboding ... in many ways seems on the verge of collapse ... I can imagine it getting good but a lot has to change to get there.”

But Linton doesn’t dwell on these things. Instead he enjoys working or sitting in his favourite Ponsonby Road coffee shop with his notebook. On sunny days he likes to take a break from his drawing board and spend some quality time sitting on his back porch, strumming his acoustic and mulling over what the next comic might be.

--

Barry Linton passed away in Auckland on 2 October 2018. A gentle soul, he was regarded by the New Zealand music and comics communities with great affection. His work inspired a generation of comic artists. Shortly after his death, the Wellington literary magazine Sport published My Ten Guitars – Linton’s final musical opus, an eight-page strip cartoon about the guitars he loved and lost during his life.