Life was never easy for Merito. Born in Whakatāne in 1938, he grew up on a family farm at Tāneatua, a small railway settlement on the edge of the Ureweras. As a child he spoke Māori as much as English, and when he was just eight years old he lost his mother to tuberculosis.

His maternal grandmother became a big influence: she would sit cross-legged, smoke a pipe and sing waiata, church songs, and ‘My Bonnie’. “She knew all the words, though she couldn’t speak the language,” he recalled to me in 2007.

In the cowshed, Merito and his siblings would listen to the radio – there was no electricity in the house – especially the weekly religious music programme from Auckland, the Friendly Road Choir. “I thought, by golly, these Pākehā know how to harmonise all right. I thought only Māori harmonised.”

In hospital the nurses gave him a guitar, and he taught himself to play.

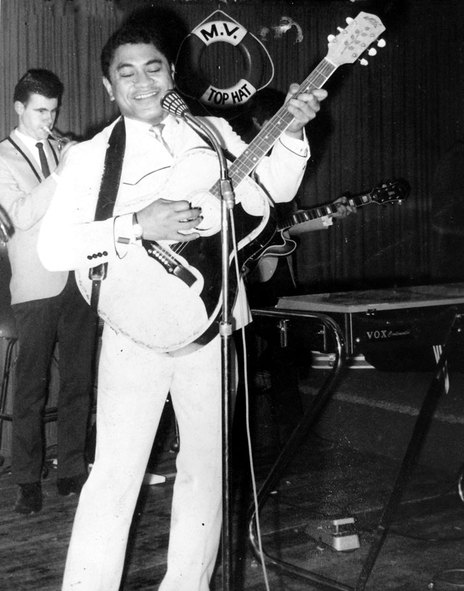

As a child, he suffered from osteomyelitis, a crippling bone disease, which meant he spent several years a long way from his family, in Cook Hospital, Gisborne – and left him walking with a limp. But in hospital the nurses gave him a guitar, and he taught himself to play. He also got a few tips from an aunt, who had distinctive rhythmic style, sweeping across all the strings with her strumming hands. Merito used the same approach with the Quartet. “It was more like a flamenco sound she had, rather than an island sound, bringing the fingers up instead of down. I learned to do that very early in life, and I got a lot of different sounds out of it. Even though I was playing just plain, basic chords.”

Merito realised that the guitar was there to accompany the voices, not drown them out, but he wanted to coax a greater variety of sounds and rhythms out of the instrument than were usually used by acoustic guitarists at the time. Like many early New Zealand rock and rollers, Merito was a big fan of Arthur Smith’s instrumental hit ‘Guitar Boogie’, which was often covered by USA country acts, young rock and rollers, and the Māori showbands. “My idea of the guitar changed with it. It gave me another insight into the guitar.”

When Merito beat Morrison in one contest, winning with his version of ‘Guitar Boogie’, Morrison suggested they get together and form a harmony group.

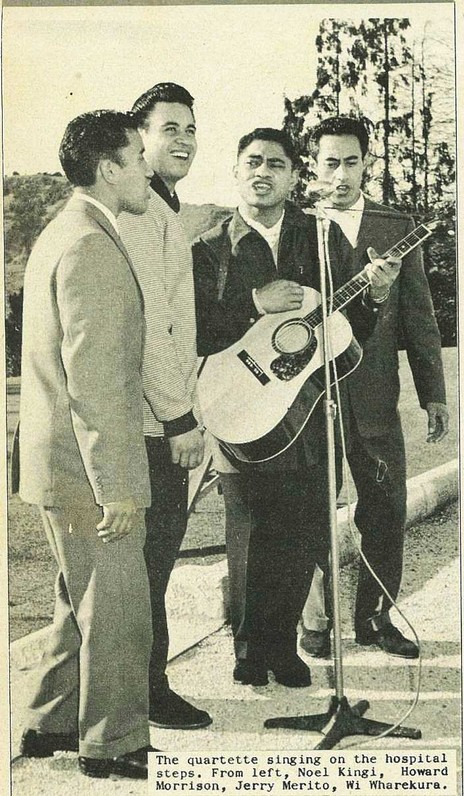

In his late teens Merito moved to Rotorua to begin an apprenticeship, and joined a Māori concert party, which meant he kept running into another performer, Howard Morrison. They also saw each other at talent quests – Morrison was impressed by Merito’s guitar playing, and Merito by Morrison’s professionalism. When Merito beat Morrison in one contest, winning with his version of ‘Guitar Boogie’, Morrison suggested they get together and form a harmony group styled after the velvet-voiced Mills Brothers.

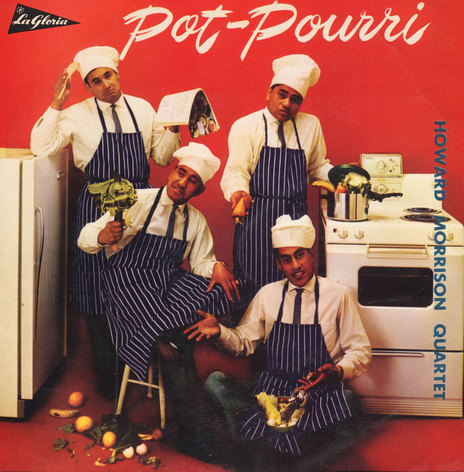

A vocal harmony group is probably what the Howard Morrison Quartet would have remained, albeit one with an eclectic repertoire of music that included US standards, Māori favourites, rock and roll, country, folk, English, Irish and Italian-style pop, spirituals and light rhythm and blues.

But in 1960 a parody took them to another level. While listening to Johnny Horton’s hit ‘Battle of New Orleans’ Merito commented, it could just as well be the battle of Wellington, or Waikato – and then thought, well, why not? He wrote the lyrics, changing the place names and incidents to events in the New Zealand Land Wars. Recorded live in the Auckland Town Hall by Eldred Stebbing, the Quartet’s ‘Battle of Waikato’ was an instant hit, selling 25,000 copies. Unfortunately, because parodies only generate royalties for the original songwriter, Merito missed out.

Another parody, ‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ – to the tune of ‘My Old Man’s A Dustman’ – satirised the “No Māori, No Tour” controversy that preceded the All Blacks’ visit to South Africa in 1960 (the host country said the team could not contain Māori players). Again, Merito wrote most of the words. In 2007 he claimed that no political statement was intended, joking “they weren’t good enough to go!” But the coda, written by Morrison, makes a barbed comment on the racism, which has saved the song from being a dated novelty: “Fee fee fi fi, fo fo fum – there’s no Horis in that scrum!” ‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ was recorded live in the Pukekohe Town Hall, and was an even bigger hit, selling 60,000 copies.

The Quartet formed in 1958, and first found fame when they recorded the perennial sing-along ‘Hoki Mai’.

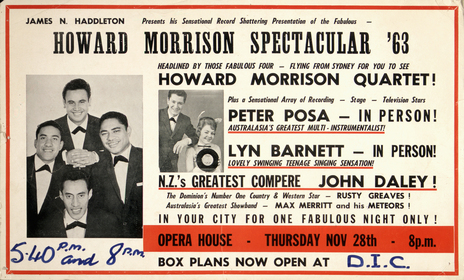

The Quartet formed in 1958, and first found fame when they recorded the perennial sing-along ‘Hoki Mai’. With an unthreatening, assimilationist humour, flawless presentation and impeccable harmonies, for five years they were New Zealand’s biggest entertainment drawcard. Then, in late 1964, Morrison decided time was up. The group gave its last show in Rotorua in January 1965, though there was a reunion tour in the late 1970s.

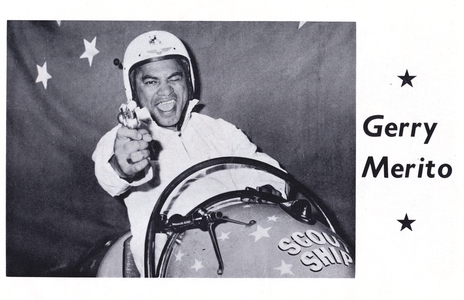

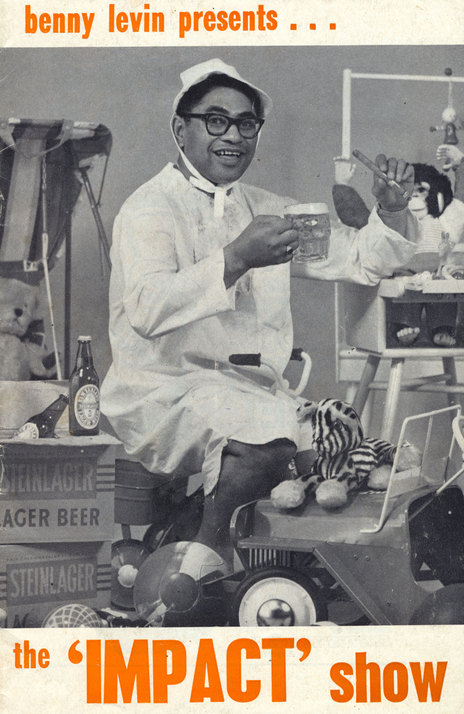

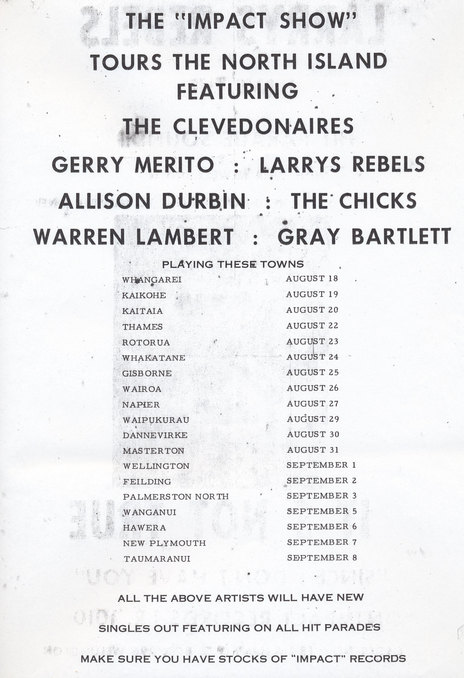

When the split came, Merito was left stunned and wondering what to do next. “I never thought the Quartet would break up. I didn’t really believe it, so I had no ambitions and nothing planned. I had four kids to worry about.” As the second-biggest name in the Quartet, it is unsurprising that promoter Benny Levin signed Merito to a record contract. His only solo album, I Must Have Been A Beautiful (Baby) Spaceman came out on Impact in 1966. Recorded live in an Auckland cabaret, it followed the Quartet’s repertoire of comedy, musical parodies, topical and Māori songs. A very moving version of ‘Pōkarekare Ana’ closes the show.

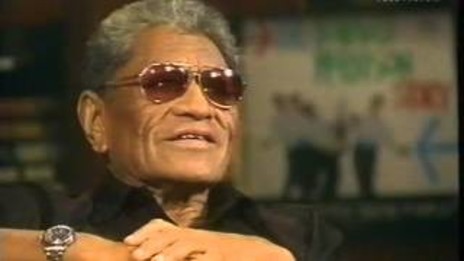

Merito did odd jobs in Auckland, including working on the wharves, and continued to entertain – sometimes on cruise ships. With his second wife, Dorothy, he moved to Perth for several years, running a lawnmower round. Returning to New Zealand in 1991, Merito and his wife settled in Cambridge, and he performed countless gigs around the Waikato, in pubs, rest homes, and RSA clubs.

On January 26, 2009, Merito died at the Waihou Tavern on State Highway 26 near Te Aroha. He was 70. After a solo gig on the weekend, he had returned to the pub on the Monday morning to pick up his gear, and suffered a heart attack. His loss was felt by thousands who had never forgotten his humour, harmonies and kindness.

But there’s also a good case to be made for Merito being the most influential New Zealand guitarist of all; certainly, Dalvanius suggested as much to me. Wherever there is a sing-along, wherever a New Zealander plays a few chords with an idiosyncratic strum – throwing in a tricky turnaround just to show you’re no mug – there goes the spirit of Gerry Merito.