Phil Warren

“Politics is show-business in drag.” It’s an oldie but a goodie, the kind of joke that cabaret queen Diamond Lil (Marcus Craig) might have used to warm up the crowd at one of Phil Warren’s Auckland clubs in the 1970s.

Singer Jacqui Fitzgerald signing records with Phil Warren around 1970

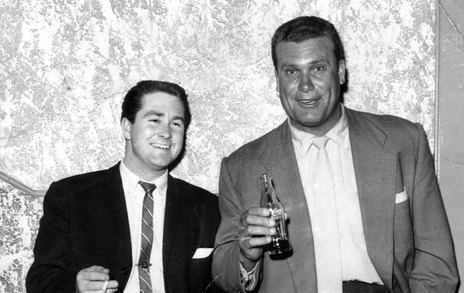

Two young but already veterans of promotion: Harry M Miller and Phil Warren in Auckland in the early 1960s.

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

Phil Warren and unknown friends in clubland circa 1959

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil Warren and an unknown touring US musican in 1959

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

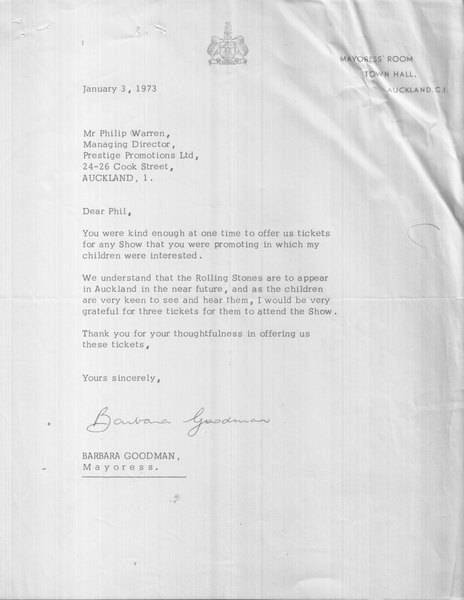

The Mayoress of Auckland, Dame Barbara Goodman writes to Phil Warren asking for Rolling Stones tickets for her kids. Later mail indicates that Phil obliged.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

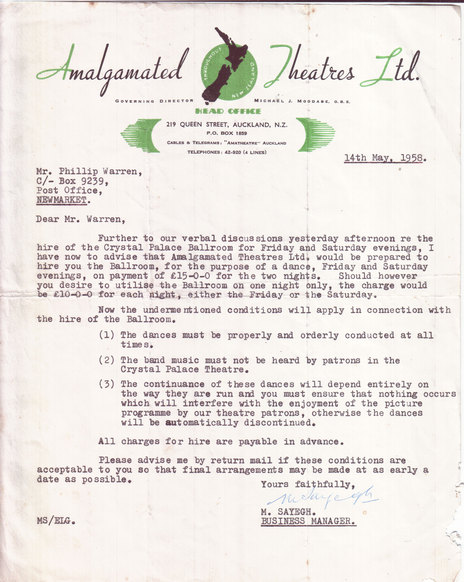

The 1958 letter from Amalgamated Cinemas renting Phil Warren the Crystal Palace Ballroom. Phil rented the room until 1973.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

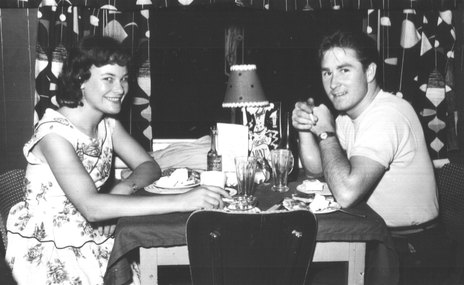

Phil and unknown friend dining in the early 1960s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil Warren and unknown friend in the mid-1960s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil Warren in the early 1960s

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

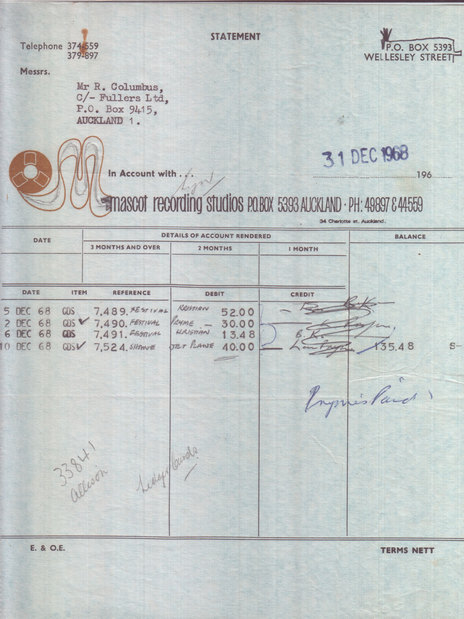

A 1968 invoice for recording from Mascot Studios (in the long demolished Pacific Building on the corner of Queen and Wellesley Streets where the ASB now sits). Each of these amounts represents a single, recorded in one day.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

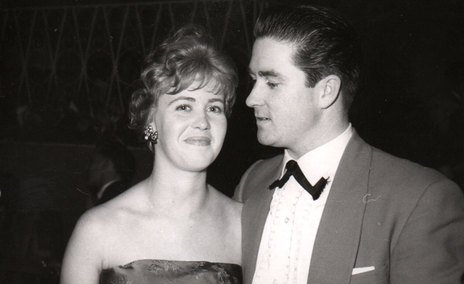

Phil Warren and Bev Mills at The Auckland Hairdressers Ball, The Monaco, Auckland, 1959

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil with unknown friend, at the Monaco Club, in the early 1960s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

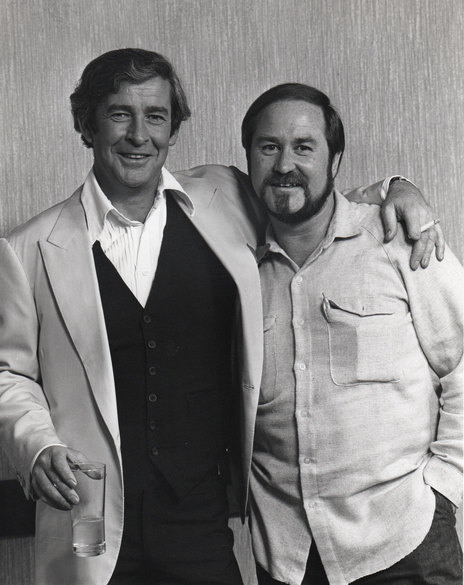

Phil and Irish comedian Dave Allen, mid-1970s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

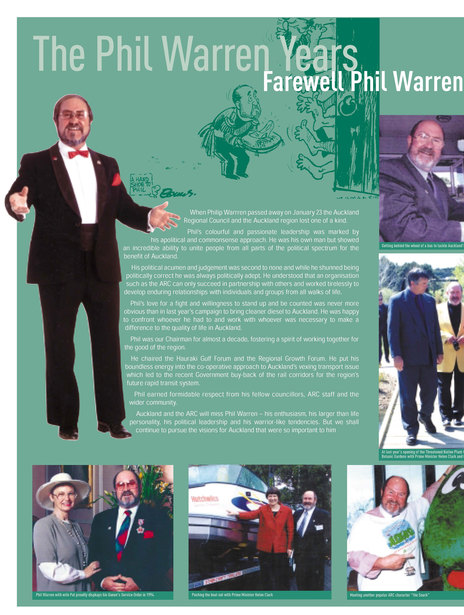

A tribute to Phil, sent out to all Auckland households after his death in 2002

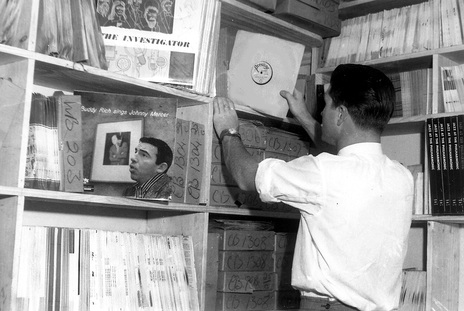

The Prestige Records stock room (which also operated as a retail store) in Newmarket, Auckland, 1958. Phil Warren is picking records.

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

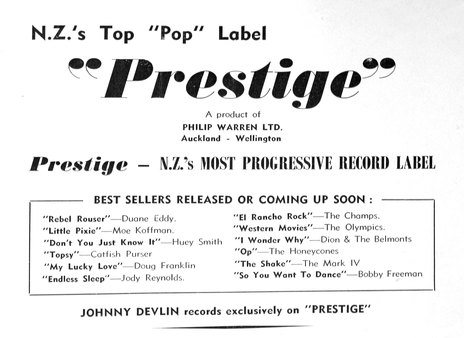

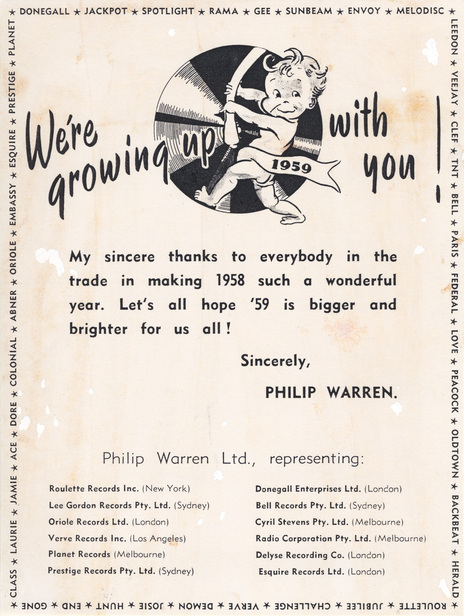

Prestige Records advert, 1959

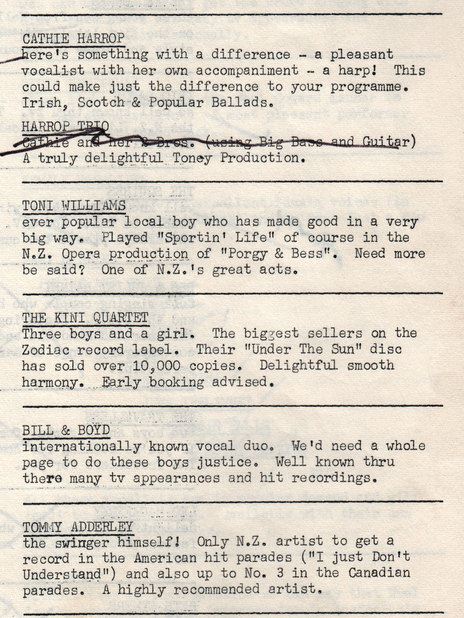

A few of the Fullers' managed and booked acts - there were 8 pages of these artists in the 1969 listings

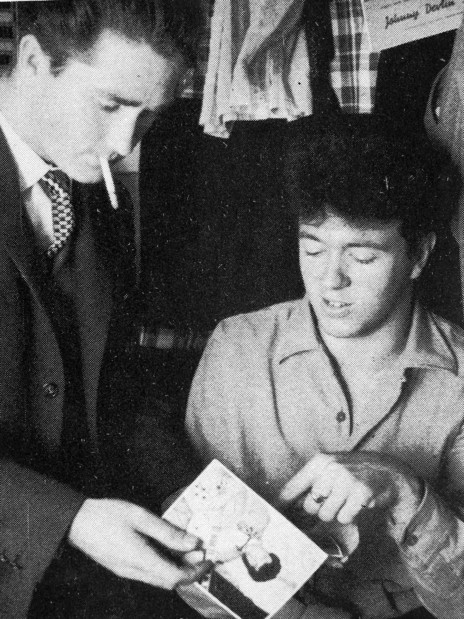

Phil Warren (centre) - aged just 19, he was the promoter for Johnny Devlin at Western Springs, February 1959

Photo credit:

Phil Warren Collection

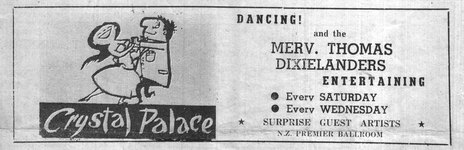

1959 Crystal Palace advert

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

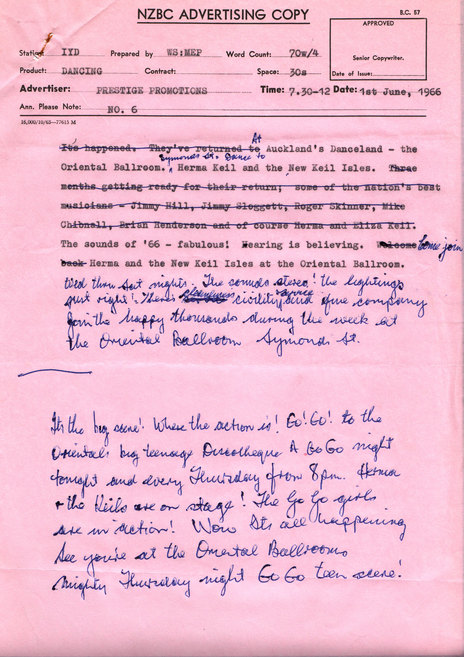

Phil's handwritten notes on the advertising copy for one of his clubs, The Oriental Ballroon in Symonds Street

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Australian rocker Johnny O'Keefe with Phil Warren, 1959

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

A gathering of managers of Phil's club empire, 1978/9: from left - standing, Billy Rae (Auckland), Nick Mills (Wellington), Trevor Spitz (Christchurch), Keith "CJ" Adams (Auckland), and two managers from Lion Breweries. Crouching we have "Raving" Ralph Cohen (Phil's club compere) and Phil. It seems to have been taken at the Mon Desir hotel in Takapuna.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

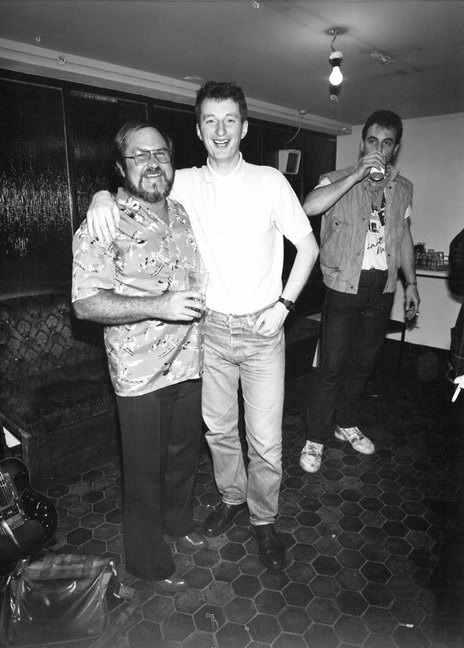

Phil Warren and Billy Bragg in the dressing room at The Galaxy (now The Powerstation), February 1987

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

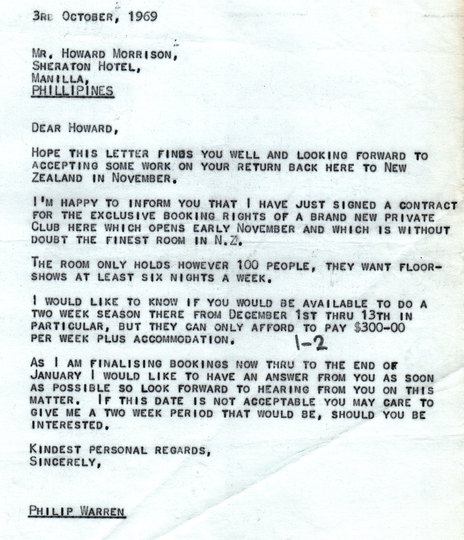

Phil Warren writes to Howard Morrison offering him dates at the new Cosmopolitan Club in Remuera. Howard telegrammed back accepting a week's work. Note the address it was sent to - Howard's work in the late 1960s was primarily in South East Asia.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil Warren and Johnny Devlin, 1959

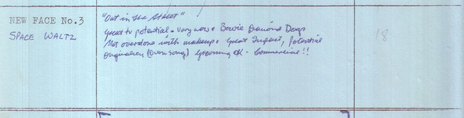

Phil Warren's handwritten notes when he judged Space Waltz on New Faces in 1974. Phil has been villified over the years as the man who who was unable to pick contemporary talent on this show and mocked it, however records show that contrary to that, he was the one judge who consistently picked the hitmakers including Space Waltz, John Hanlon and Split Ends. One note states a Shona Laing song was "too good for radio".

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

A 1959 trade advert from Phil Warren for Prestige. This is the orginal copy for the advert, as proofed by Phil.

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

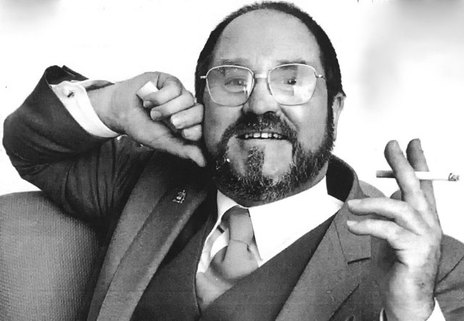

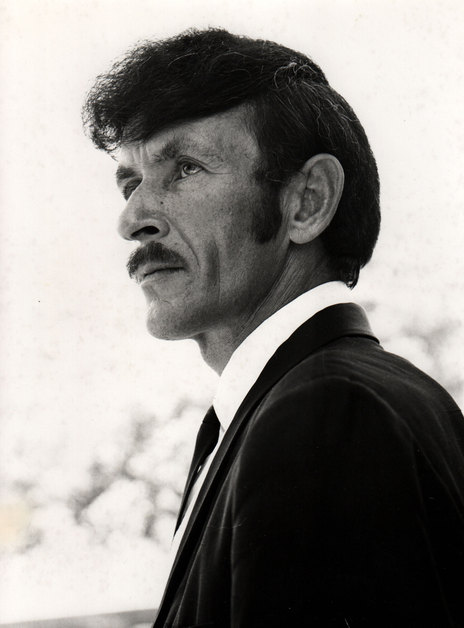

The late Phil Warren in an official shot taken in the late 1990s

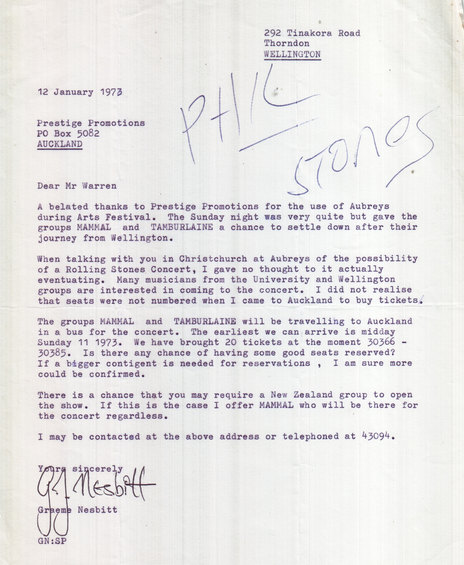

Welllington promoter/manager Graeme Nesbitt on the hunt for good seats at The Rolling Stones for both the bands he managed, Mammal and Tamburlaine

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

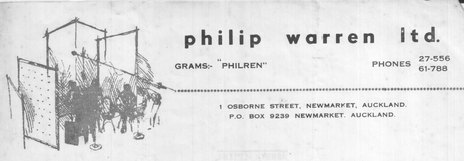

Phil Warren's 1950s business slip

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

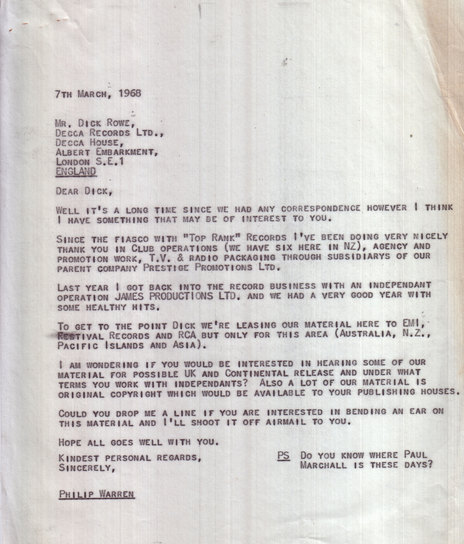

Phil Warren writes to Dick Rowe, the man who famously turned The Beatles down, offering New Zealand records for UK release. Rowe would write back asking Phil for copies, which Phil supplied with covering notes, some brutally honest.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Keith "CJ" Adam's, Phil Warren's right hand in running clubs throughout the 1970s and 1980s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil Warren on the drums, 1958

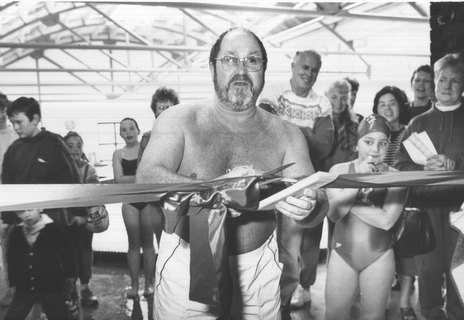

Phil the local body politician opening a swimming pool in the 1990s

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

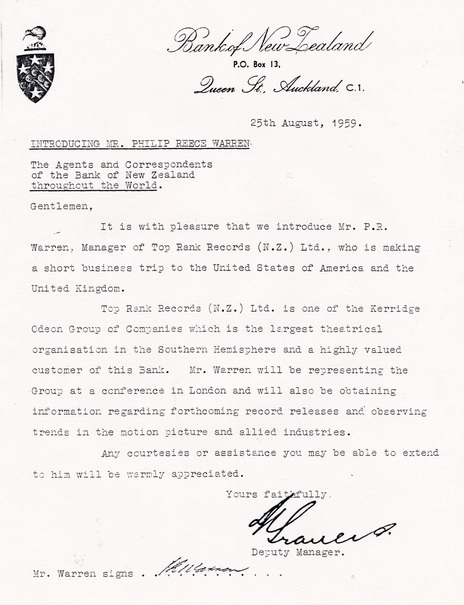

Phi Warren heads off to the US and The UK to represent Allied International in 1959

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

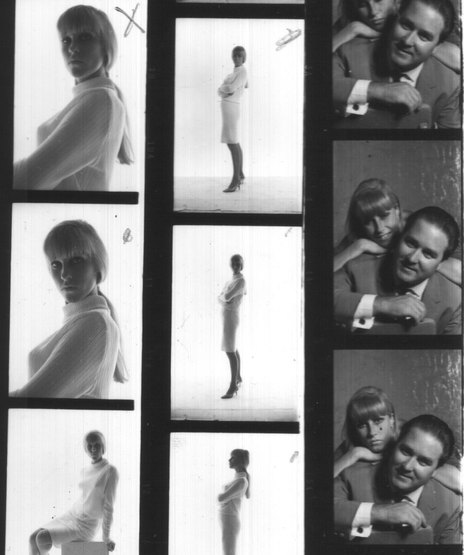

Sandy Edmonds and Phil Warren - outtakes from a 1968 proof sheet

Photo credit:

Phil Warren Collection

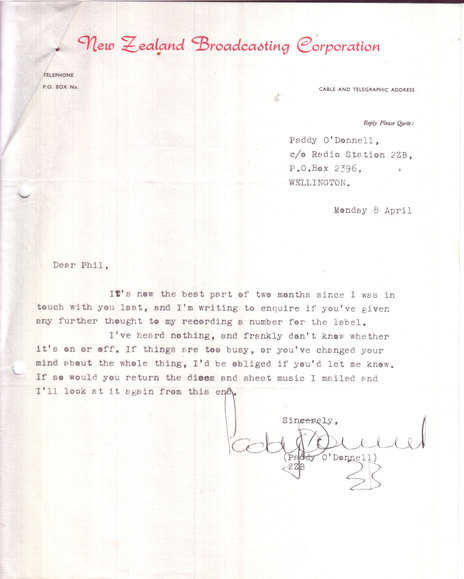

The year is unknown but famed broadcaster Paddy O'Donnell is angling for a recording deal with Phil Warren, seemingly without luck

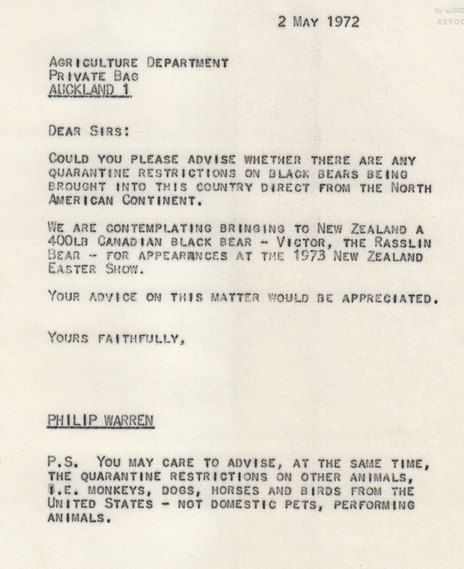

The ultimate showman - in 1972 Phil decided that he wanted to import a Canadian Black bear for the Easter Show. The PS is fabulous.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Phil and friend at The Monaco Club, 1959

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

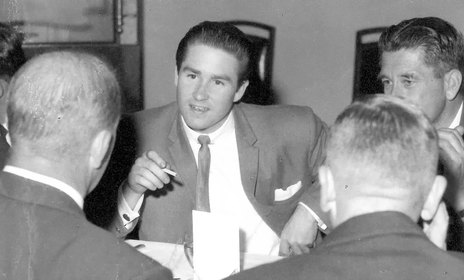

Phil Warren negotiating

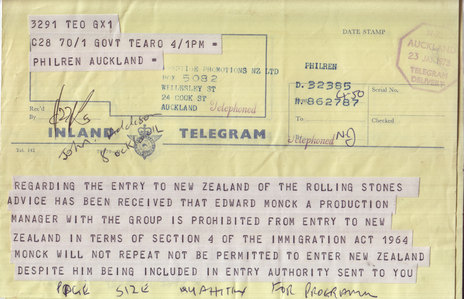

Phil Warrens' Rolling Stones tour in 1973 was a incredibly smooth and perfectly produced show that was booked and promoted in a very short time. The only hiccup came when production manager Chip Monck was banned from New Zealand. Why? Because he was the voice warning about bad LSD at Woodstock ("The brown acid that is circulating around is not specifically too good...") and co-promoted the infamous Rolling Stones concert at Altamont.

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

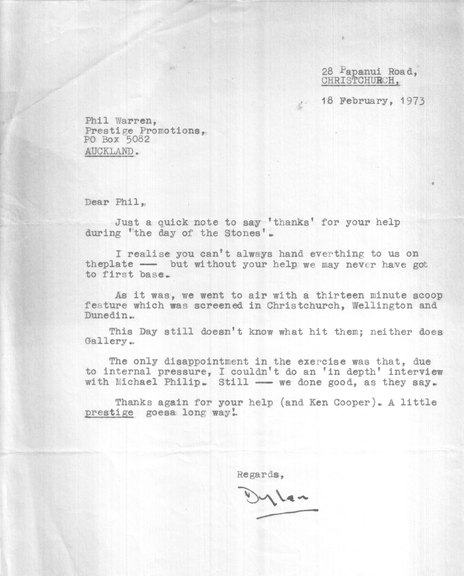

Dylan Taite writes to Phil Warren after The Rolling Stones gig in 1973

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

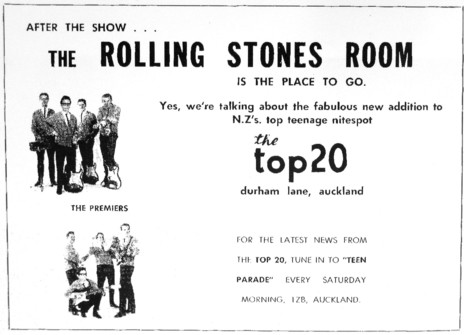

Never one to miss an opportunity, Phil Warren's The Rolling Stones room was at The Top 20 in Durham Lane, Auckland

Singer Jacqui Fitzgerald checks her bio with Phil Warren around 1970

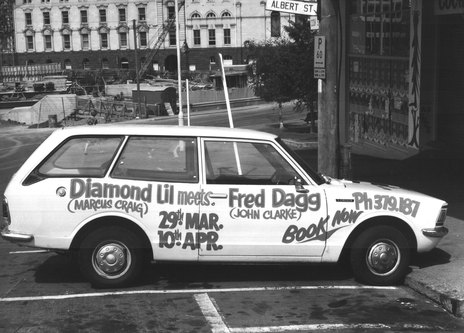

Outside the Ace of Clubs, Cook Street, Auckland, 1976. Diamond Lil and Fred Dagg were briefly a double-act after their success recording 'Gumboots'

Photo credit:

Phil Warren collection

Two showmen who, between them, dominated the Auckland live scene for some 20 years - Phil Warren and Benny Levin at the 1990 APRA Silver Scroll Awards

Trivia:

In 1959 Phil Warren planned to bring Elvis Presley to New Zealand. In partnership with Australian promoter Lee Gordon, Warren pitched US$130,000 to cover 5 Australian shows and one New Zealand show. It was not to be.

In 1958 Phil Warren was drafted into the airforce under the Compulsory Military Training programme. Whilst based at Whenuapai he ran Prestige in the weekends until he managed find a way to excuse himself from CMT.