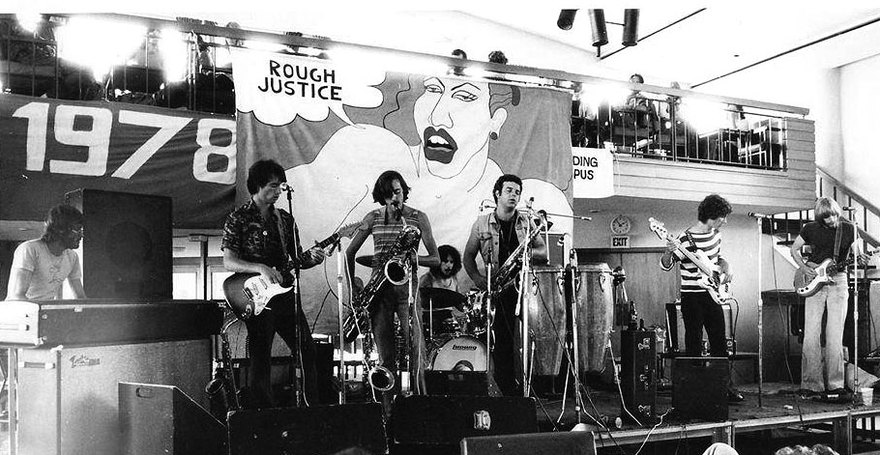

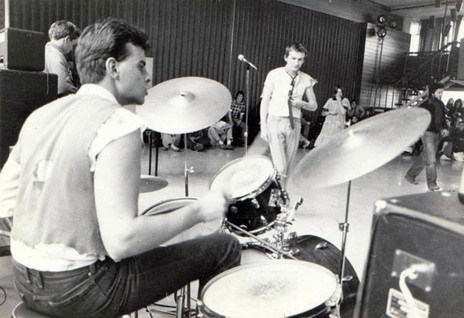

Nick Bollinger (in striped shirt) with Rough Justice in 1978 at Victoria University's Union Hall. - Nick Bollinger collection

“I gotta go / I’m gonna raise hell at the Union Hall …” Mick Jagger hollered in the Rolling Stones’ 1972 stomper ‘Rip This Joint’. The lyric always had a particular resonance for me. That was the year I started going to concerts in the Union Hall.

No, I don’t think Mick was singing about the same Union Hall, and I didn’t raise much hell there. But in the early 70s the Union Hall (now known as the Hunter Lounge) of Victoria University’s Student Union Building was one of the few places in Wellington where a teenager could go to hear live music – to me it was a musical sanctuary.

I once tried to list all the bands I saw there over a period of two or three years; I counted dozens, and there were a few I had no doubt forgotten. Most were Wellington bands such as Mammal, Tamburlaine and Blerta – all of which I saw many times – but there were also national touring acts, among them Billy TK and the Powerhouse, Split Enz, Space Waltz, Butler, Dragon, and occasionally international visitors like the veteran bluesmen Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.

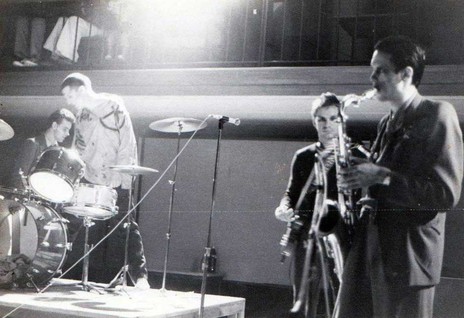

Suburban Reptiles with stand-in guitarist Johnny Volume at the August 1977 Students' Arts Festival at Victoria University. The band are setting up and The Scavengers' Des Truction is also seen. From left: Des Truction, Buster Stiggs, Johnny Volume and Jimmy Joy. - Photo by Wayne Hunter

The Union Hall would host many other acts over the decades, often at significant moments: The Suburban Reptiles in 1977 on the first local punk tour, The Fall in 1982 on their first New Zealand visit, The Birthday Party in 1983 just before their demise. In recent years the room has beed renamed the Hunter Lounge, causing some to confuse it with the oldest building on campus, the imposing, gothic Hunter Building.

More recently, as the Hunter Lounge, the room has featured Aldous Harding, Marlon Williams, and countless others. With a capacity of around 800 it was the ideal venue for a medium-size show. There were balconies at either end overlooking the main area where you could choose to sit and watch, or you could mill amongst the mostly dancing crowd down below.

The Student Union Building was officially opened by the Minister of Education, Philip Skoglund, on 10 June 1961. The Union Hall was a large room on what was then the building’s top floor. It was used for meetings, forums, and Orientation “hops” but was also available to university clubs, though the Folk Club and Jazz Club – the two most prominent music clubs on campus – usually held their concerts in smaller common rooms or the more formal Memorial Theatre.

Graeme Nesbitt calls for volunteers, Salient, 1970

In 1969 Graeme Nesbitt, a student and Folk Club member with a flair for creating a scene, formed the Victoria University Rock and Blues Society, and began booking the Union Hall for rock shows. Among the first bands he brought to the hall were Auckland blues-rock legends The Underdogs, fronted by local guitar hero Harvey Mann. Most students had never encountered anything so loud and hairy. The Underdogs can briefly be seen in concert at the Union Hall in Geoff Murphy’s film Tank Busters on NZ On Screen.

In 1970 Nesbitt was appointed controller of the National Student Arts Festival; that year, it was Wellington’s turn to host. Rock music made up a major part of the programme. Reflecting on the festival’s musical component, Dennis O’Brien noted in student newspaper Salient: “If the music was for the most part of a high standard, it was also generally a mite samey; most of the groups were big and loud, playing heavy rock ad nauseam, while some built their whole repertoire around a succession of Cream-inspired bass riffs.” He cited Wellington trio Tricycle and Dunedin outfit Anthrax (who predated the American band of same name by a decade) as particular offenders, “their music without the redeeming quality of good vocalising.” But he praised Dunedin’s Pussyfoot and locals Highway and Gutbucket, while “local rave Mammal … at least looked as though they were enjoying whatever they were doing.”

Playing a mixture of complex originals and eclectic covers, Mammal would feature prominently in Rock and Blues Society shows over the next few years. Initially a four-piece (Simon Morris, Tony Backhouse, Bill Lake and Mark Hansen) they eventually consolidated around a core of Backhouse, singer Rick Bryant, guitarist Robert Taylor, violin player Julie Needham, bass player Mark Hornibrook and drummer Kerry Jacobson. The fact that most of the group had been students at Victoria and a couple were now junior lecturers made them the quintessential “university band”. Morris and Hansen moved on from Mammal to form the more pastoral Tamburlaine – who would frequently share bills with Mammal.”

It was the era of the Vietnam War and sometimes the venue would double as a rallying place. A notice in a 1972 Salient encouraged students attending an anti-war protest at Parliament to gather beforehand at a rock concert in the Hall “to prepare for the long march ahead”.

Mammal / Arkastra poster for a gig at Victoria University, Wellington, December 1972 - Peter Blake collection

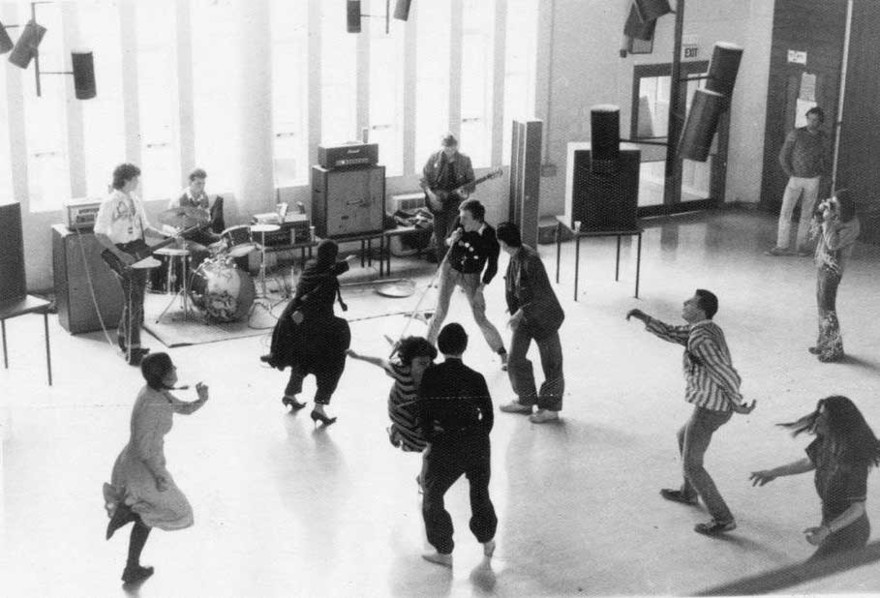

Though billed as concerts, the Union Hall shows were really happenings that followed the do-your-own-thing ethos of the times. Crowds would sit cross-legged on the linoleum floor and watch the bands until the free-form dancers took over. Plus, there were the lights. Inspired by the psychedelic light shows famously found at venues like the Fillmore in San Francisco, Peter Frater – who had been involved with music and drama events at Victoria since the early 60s – devised a light show of his own. Using a mixture of oil and coloured dyes compressed between layers of glass, he made projections which threw colourful bubbling patterns onto a screen behind the band. By adding effervescent salts to the coloured oils, he would punctuate the projections with visual explosions.”

Marc and Todd Hunter at the Union Hall, Victoria University, 1975. - Photo by Larry Jordan. Richard Driver collection

Frater would simultaneously screen 16-mm movies. A favourite was a science documentary depicting the lifecycle of the blowfly. Sometimes he would place live wetas and slaters on the tray of an overhead projector and these would appear, hugely magnified, crawling across the screen. To achieve all this he would have up to a dozen projectors operating at once with half a dozen or so recruits to help operate them. There were constant hazards – blown bulbs, electric shocks – but when everything was working the effect was suitably mind-bending.”

Robert Taylor, Union Hall, Victoria University of Wellington, 1975 - Photo by Larry Jordan. Richard Driver collection

If it was an Orientation event, or a special hop to mark the start or end of a term, there would be a bar where tickets purchased with ID could be exchanged for drinks. But normally the Union Hall concerts were alcohol free; it was the reason my friends and I, who were pretty obviously under the legal drinking age, were allowed in. A bottle of something might be smuggled in under a coat and one soon learnt to recognise the earthy smell of marijuana. But the general lack of ingestible stimulants threw the focus on the music, which was what most people seemed to be there for – though there was the odd unreconstructed pisshead like this first-year student who complained in the Salient letters column:

“At Canterbury they have a Stein (Pissup) each weekend. These sometimes have a band and if not, just records. There is no admission charge but a student ID has to be shown. Outside the hall tickets can be bought for ale (20c can) and without being questioned at the door by some bow-tie clad prick. Surely the rules in the universities don’t vary so much that one can have a good piss up each week and we have to manage with one a term?”

At the start of 1973, Salient ran the invitation: “All musicians. Light and sound technicians, groupies, dealers and anyone interested should attend the BLUES/ROCK AGM, Monday 26th March, 6.00pm in the Union Hall.” It was going to be a big year for rock concerts.

The security, all motorcycle enthusiasts, looked like textbook bikers: burly, bearded, long-haired and tattooed.

A familiar presence around this time was that of Graeme Nesbitt’s younger brothers, Robert, Bruce and Greg, who Graeme employed to provide security. All motorcycle enthusiasts, they looked like textbook bikers: burly, bearded, long-haired and tattooed. Just their intimidating appearance was usually enough to maintain the peace. Once, in the 80s – after working security for a ZZ Top concert – they were mistaken by fans for the band itself. There had been a moment of cognitive dissonance when, asked which part of Texas they came from, they replied “Upper Hutt”.

When the Hamilton-based 1953 Memorial Society Rock’n’Roll Band brought their retro act to the Union Hall in 1973, Rob Nesbitt added a touch of actuality to ‘Leader of the Pack’ by riding his motorcycle up two flights of stairs and onto the Union Hall stage, where he revved it at appropriate moments in the choruses.

That year Dragon, still years away from Australasian stardom, played some of their first shows outside Auckland there, debuting originals soon to be heard on their first album, including ‘Weetbix’ and ‘Universal Radio’.

By the mid-70s, music on campus was more plentiful and varied than ever. The Student Arts Council had been founded in 1972 to “encourage, promote and develop the practice and appreciation of culture and the arts” within the student bodies of all tertiary educational institutions. Under its co-director Graeme Nesbitt and his successor Bruce Kirkland it developed a touring circuit, taking the kind of shows I was catching in Wellington to campuses all around the country. For bands who played original material, less suited to the pub circuit, it meant a chance of survival.

Alastair Riddell/Space Waltz university tour handbill, 1975

Space Waltz, having stepped into the nation’s living rooms via the TV talent quest New Faces, still saw the student audience as being their chief constituency. Even so, campus critics were not wholly enthused by their 1975 appearance at the Hall. Gary Henderson found frontman Alastair Riddell looking “like a cross between Dracula and Twiggy”, fronting a band that was “loud, full of interesting bass work, short harmony lead runs, and solid keyboard and percussion backing”. But Henderson felt the frontman had underestimated the discerning Union Hall crowd. “One thing that got my back up slightly (me being a peaceable character normally) was Alastair’s attitude that he was playing to a crowd of teeny-boppers. The group was playing to a critical, appreciative audience who wanted something more than volume and beat. We were accused of being inhibited and uninvolved because we did not cheer madly and clap and stomp along with the music.”

That year the executive of the Victoria University of Wellington Students Association fielded a request from the Divine Light Movement to book the hall for a one-off concert, but the venue was still normally available only to student organisations. A folk concert during Orientation in March 1976 drew over 200 people to hear Marg Layton, Jean McAllister, Dave Hollis and the trio Jade. Also, the hall was filled beyond capacity for a show by Auckland folk-rockers Waves, causing complaints of discomfort among some of the punters and discussion at a Students Association meeting of the need to increase security “to make sure that the Union building could be sealed off once the Union Hall was full.” In July, the Golden Horn Big Band (soon to become known as The Rodger Fox Big Band), The 1860 Victualling Company (The 1860 Band) and Palmerston North’s Glass Menagerie joined forces at the end of exam week for a jazz extravaganza.

A rock’n’roll schism took place in 1977. Though long hair and flared denim were still a common sight on campus, and epic guitar solos could still be heard ringing from the Union Hall, there were stirrings of a new movement: punk.

The Scavengers at Victoria University's Union Hall in August 1977. Various Suburban Reptiles are seen dancing. - Photo by Wayne Hunter

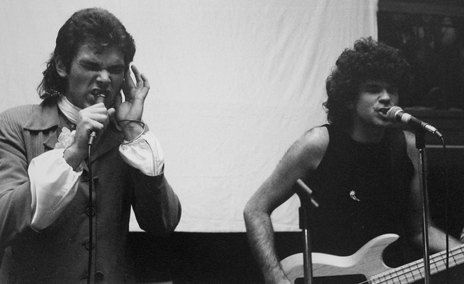

By this time, I had finished school and joined a band, Rough Justice, led by former Mammal singer Rick Bryant. We would play in the Union Hall on a number of occasions over the next couple of years, but we were away on our first South Island tour when punk first came to campus.

The Scavengers at Victoria University, August 23, 1977. - Wayne Hunter

It was Victoria’s turn to host the annual Student Arts Festival and with Graeme Nesbitt out of commission due to a marijuana bust, some odd programming decisions were being made. One was to put one of the country’s flagship punk groups – Suburban Reptiles – on a bill with Living Force, a band of Hare Krishna devotees led by former Underdogs guitarist Harvey Mann and specialising in long, cosmically-inspired guitar solos. As Chris Bourke, who witnessed this clash of cultures, was to note: “Living Force … were instantly rendered irrelevant”; the Reptiles, he wrote, were “apocalyptic. Like musical napalm they laid waste to anything that whiffed of long-hair and long guitar solos.”

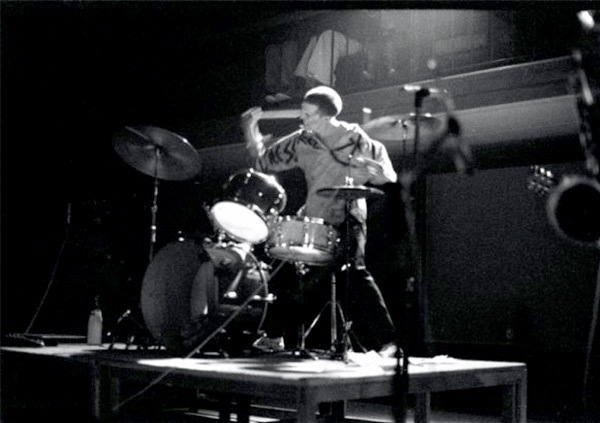

Buster Stiggs, shortly before the drumstick "incident", Union Hall, Victoria University of Wellington, August 1977 - Photo by Stuart Page

But the Reptiles’ sonic weaponry was not to the tastes of the soundman, a relic of the hippie era, who argued with the group before their set had even got underway, causing drummer Buster Stiggs to hurl a drumstick into the crowd in frustration, mildly injuring a member of the audience. The whole fracas delighted Redmer Yska, a journalist at the time for Truth newspaper, who reported the incident in lurid tones (see Yska’s AudioCulture story “Suburban Reptiles go south”) providing the punks with the kind of publicity money can’t buy.

Though the violence was very rarely instigated by the bands, punk attracted new punters to the Union Hall, some of whom came looking for a fight. When The Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow – a package of groups from the Auckland-based Propeller label – played an Orientation gig in March 1981, Wellington skinheads and boot boys were among the crowd. In an AudioCulture article tour manager Simon Grigg recalls the whole thing deteriorating into a violent brawl in which members of Blam Blam Blam, The Newmatics and Screaming Meemees gave as good as they got, some using their instruments as weapons. That year tensions around the impending Springbok tour added to the volatility.

The manager of the Screaming Blam-matic Roadshow complains to Salient about the bands' rough treatment at Victoria University's Union Hall, August 1981

The Nesbitt brothers were on hand if there was any trouble. Usually, their mere presence was enough to dissuade would-be scrappers. “Though I’ve got to admit it,” towering and tattooed Rob Nesbitt once confessed, “when we started to get the punks, the ones with all the metal, safety pins and that, when you get them in a headlock, you’d just give them a tweak and they’d bleed like hell. From the eyebrows!”

In a post-punk world, the Union Hall would continue to host leading-edge acts. The Fall played there in 1982, with locals Naked Spots Dance opening. (A six-disc box set of live Fall recordings from this period includes several tracks from this tour, with at least one from the Union Hall.) The following year, The Birthday Party – on the brink of disintegration amid drug habits and internal friction – rallied to play a legendary set. In 1985 the Topp Twins teamed up with Midnight Oil’s Peter Garrett for an evening of anti-nuclear agitation, and the following year the Students Association joined with TVNZ’s Radio With Pictures to promote a concert by the country’s most political reggae bands: Herbs, Aotearoa and Dread Beat & Blood. Several South Island bands from the Flying Nun convent – Sneaky Feelings, the Verlaines, the Bats, the Chills – stopped by, as did a string of international visitors including Billy Bragg, The Go-Betweens and Schnell Fenster, Violent Femmes, The Mad Professor, Throwing Muses, and Pop Will Eat Itself.

But by the early 90s student culture had undergone a sea change. The neoliberal reforms of the 80s and introduction of user-pays education encouraged students to see themselves as “clients” rather than a community. Radio Active, the student station which had begun in 1976 and been an important promoter of campus concerts, parted with the Students Association in 1992 to become a private, semi-commercial broadcaster. That same year the Student Arts Council was dissolved. As the decade wore on, the lowering of drinking ages and a raft of new media competed for students’ leisure time.

What’s more, the requirements of a resource consent, introduced after legal action was taken by an irritable campus neighbour, saw a reduction in the number of shows allowed in the hall. There were still some memorable ones: Fugazi in 1997, The Shins in 2005, NOFX in 2007. But live music ceased to be the vital part of university life it had been in the 70s and 80s. In 2011 perhaps the last great Orientation package brought MGMT, De La Soul and Unknown Mortal Orchestra to the hall.

Aldous Harding at Wellington’s Hunter Lounge, touring the Designer album, 30 August 2019. - Kirsten Johnstone

The following year, legislation introduced by the Act Party removed compulsory student body membership, drastically reshaping the Students’ Association’s budgets and decimating its ability to promote events. The hall has continued to host the occasional concert. Marlon Williams in 2018 and Aldous Harding the following year saw teenagers swaying side by side with sixty-somethings who had frequented the hall in the 70s. But current constraints make it difficult to mount the kind of shows there that today’s students might rally to.