Rough Justice in Queenstown, 1978: Martin Highland, Peter Boyd, Bernadine Doyle, Peter Kennedy, Stephen Jessup, Rick Bryant, Janet Clouston, Nick Bollinger and Mike Gubb (next to his dog, Rhodes). - Mike Gubb collection. Photo by Alison Clouston.

Fresh from 12 months in Wi Tako prison (now Rimutaka Prison) for cannabis related offences and hungry for the road, Wellington R&B singer Rick Bryant launched a new working band in August 1976 that he dubbed Rough Justice. The double-barrelled name defiantly referenced his immediate past.

Rick Bryant: “I started putting Rough Justice mark one together when I was still in jail. I just wanted to get cracking. I wanted to have a real job as soon as I got out. Partly, because I wanted to get on with it, partly, it was what I’d got used to doing. At the same time choosing the name Rough Justice was a confrontational gesture and a way to try to turn bad fortune into better fortune.

Rough Justice Mk.1, Wellington, 1976 – Mike Farrell, Patrick Bleakley, Steve Garden, Rick Bryant and John Key

“A fortunate coincidence was [promoter and friend] Graeme Nesbitt was looking to collaborate on a band for Patricia Watson. Pat was a bit of an agent, a bit of a hustler. And in particular, she was acting as an agent for the late Mike Farrell (Tom Thumb). I’d never known Mike well. I just knew he was a great player and he wanted to do something similar to what I wanted to do. Which was put a working five piece together.

“Mike had a bit of a thing about Lowell George. He wanted a Little Feat clone band to some extent and I was quite happy with that for the meantime because I just wanted to get a strong band going. Mike came with a drummer with a great reputation, Steve Garden. I’d been hearing about how good he was.

“[The bass player was] Patrick Bleakley, my mate who was in BLERTA for a long time. BLERTA went through stages of being dormant, in hibernation. They would get together for special occasions. We had done a gig while I was in jail. I was able to do it on weekend leave, probably illegally.

“And there was a keyboard player, John Key, and he was quite experienced and he wanted to play similar music to us. We had six members. Fane Flaws was singer and guitarist in this band originally.

Rough Justice Mk.2 - Martin Highland, Peter Kennedy, Nick Bollinger, Rick Bryant, Steven Jessup, Mike Gubb, Peter Boyd

“After a very short time, one practice maybe, Mike Farrell said to me privately, ‘Look, I can’t be in a band with Fane. Our guitar styles are too different. Our approach to writing is too different.’ It was just unthinkable really. He had to go, which I did forthwith, but not without quite a few crankings of conscience. But I could see that he was right. Fane eventually came to think it was funny and we could joke about it.

Rough Justice quickly became part of a wandering performing tradition set in recent place by BLERTA and Mammal.

“We had this bus with Rough Justice on the side in letters two-and-a-half feet high done in this circusy high art style. It was my third bus. Mammal used to rent the BLERTA bus for short tours and then Mammal had an old bus – a Leyland SP3 – very old heavy bus – no power steering. Then for Rough Justice, I bought a faster, petrol bus.”

Rough Justice quickly became part of a wandering performing tradition set in recent place by BLERTA and Mammal in the first half of the 1970s, groups in which Bryant had also featured. The evening’s soundtrack arrived when the Rough Justice bus rolled into town.

The four year cultural odyssey that followed left few corners of New Zealand untouched as two successive versions of the roving troupe found an audience amongst the still kicking counter culture on university campuses and in urban pubs and country halls.

Rick Bryant: “Rough Justice mark one got some quite good pub bookings, maybe through Pat Watson. There was the Victoria University Common Room because a lot of the gigs were organised by the University Blues Club and that was Graeme Nesbitt, who was doing his promoter’s apprenticeship being campus promoter. He was very good at it. He was inventing it. There were other people doing it too, but he had energy and imagination. Graeme and I were pretty good friends and he was involved in quite a few of our enterprises.

“Our first couple of [out of town bookings] came through our Christchurch contacts. We had several really good weeks in pubs in Timaru, Christchurch and Dunedin. We went to the South Island for one week and while on the road we picked up other gigs. We went for one and stayed for five and at the end of the five the band was really shaking down and the word had got around the pub circuit that Rough Justice mark one were a good thing to book because people were talking. It was a good band.

Up north, Rough Justice mark one did a week in Whangarei before Christmas [1976], and on Christmas day they drove non-stop to Queenstown after getting to the [inter island] ferry just in time. More or less driving non-stop. Then there was University of Auckland orientation in March 1977.

Rick Bryant remembers the show as being Rough Justice mark one’s best gig. “We had a very discriminating audience. They loved us. Crowds used to be so enthusiastic.”

Other hotspots included Hamilton and Timaru. “We had a kind of spiritual home in Hamilton. Rough Justice mark one used to do very well there. The reason was Mike Farrell had a strong following in Hamilton and he deserved it. He was a local hero. There were two places they just loved us, one was Hamilton, the other was Timaru. Timaru was good in those days. It was still an active port. The pub could be full of seamen on a Monday and Tuesday night.”

As good as Rough Justice mark one got, trouble bubbled to the surface in early 1977.

As good as Rough Justice mark one got, trouble bubbled to the surface in early 1977. Some of the musicians didn't like the way Bryant ran the band. “The way I did the booking. The way I did the money. The way I made the arrangements. And in particular the fact that we had a kind of all round worker, who was Paul Matthews, a guy I knew well.

“I was pretty paranoid when I first got out of jail and when I had confrontations with employers, Paul had a very smooth manner and he was good when I wanted somebody else to make a phone call. He was tall and strong and could turn on an extremely intimidating manner, which actually helped us get paid a couple of times. He was a middle-class boy. And what I mean when I say that he had a smooth manner, he had a polished kind of manner, but also I have seen him turn the menace on, a bit like a menacing lawyer, with a guy who was reluctant to keep to a deal we’d made, a publican in Napier. I was impressed.”

Disgruntled band members wanted Matthews to be sacked. Bryant recalls responding, “‘Fuck off, I handle the cash and it’s all straight up. What we’ve got, we’ve divided equally.’ That’s the way I’ve always done the money in all my bands. We work out the net and we split it. We’d get $140 some weeks and $80 other weeks. In modern money those sums would be more realistic. Also, I overreact when people accuse me of dishonesty. I would despise to take my co-workers’ money. I’m a socialist.

“Over the years every band leader gets accused of this and some of them are taking a booking percentage or a lead in percentage, but I never have. The reason I’m sensitive about it, is because I’ve made the sacrifices you have to make if you’re going to be honest.

Rough Justice on their first trip to Auckland, 1977. Left to right: Steve Jessup, Peter Kennedy, Rick Bryant, Simon Page, Nick Bollinger, Martin Highland - Photo by Murray Cammick

The band imploded in April 1977, at the end of what had been a busy nine months for the hard working group. There had been plenty of memorable shows along the way studded with R&B, Little Feat covers and Mike Farrell originals and Rick Bryant wasn’t about to give up now. He quickly formed a new Rough Justice.

“I had momentum by this stage. I had bookings. I had the bus. Everything was set up to continue so I went back to Wellington and put together a band in no time. I got hold of Nick Bollinger. I’d been talking to a very good pianist called Simon Page. I didn’t know this guy from Adam, but his chops were bloody good. He’d left a pop band and he wanted to get into a band quickly.

“I had a practice room organised. And when I spoke to Nick, he said, I can bring a drummer if you like [Martin Highland]. And my old friend Peter Kennedy heard I was putting a band together and said ‘I know I’ve acquired an extremely bad reputation as an out-of-control alcoholic. I know that I’ve done a lot of things that I’m ashamed of but just give me a chance.’ Give us a chance and I won’t let you down.’ We’d been mates for a long time. I said sure. And he didn’t.

Kennedy designed a lot of the Rough Justice posters. “He’s a really good artist. That’s one of the reasons we’re friends. He went to art school and I went to university, but I suppose we actually met because we both smoked pot. He’d been in a few bands. He was a good guitarist. I admired his guitar playing already. Very unusual, completely self made style. He could do elements of people’s style when he wanted to.

“He was extremely serious and fussy about his sound. It was the days before tuners and good machine heads. Some of the bloody guitars you were expected to play didn’t tune very easily and he had ultra light strings that went out quickly. Pete was never happy with his guitar and amp for years and years.

“I knew that Nick was the right kind of bass player. Martin Highland, the drummer he brought, was very young, very keen and liked all the right [role models]. I liked the fact that he was straight, because as far as smoking pot goes there are quite a few good drummers whose time is affected by being stoned.

“Nick was great. Peter worked out pretty well from the first practice. Nick also brought another guy, his close friend Steve Jessup. I had to eventually fire him from Rough Justice for being a bit too rough and not doing his homework on his licks. He played sax as well which is why I took him. He not only could play guitar in an enterprising way with once again the right role models. Nick and Martin and Steve had already elected to be R&B stylists. Steve eventually got really good and was a member of the Windy City Strugglers for a while.

“We practised in an abandoned house owned by the Bank of New Zealand, whose hapless property manager used to come around during early Rough Justice practices. I’d say, ‘I’m sorry mate. I’m not actually the tenant. The last person who was a tenant here said that I could practise here during the daytime. They said they do intend to pay some rent sometime, but more than that I can’t help you with.’ And this suit was probably used to dealing with a different kind of person. When you manage a property portfolio you didn’t expect six crappy flats behind the Chinese Embassy. It was clear that despite being an older guy in a suit that he was intrigued by the music.

"You had to do Stones covers, which everyone danced to at parties. They still do."

– Rick Bryant

“We practised there eight hours a day. We did three week's hard practice to get three sets – a pub repertoire – and it was mainly R&B covers, like Mammal. This was still a stage in the evolution of New Zealand music where a working pub band, their best chance of wider credibility and a sustainable level of popularity was (among other things) to be an adequate Stones cover band.

“You had to do Stones covers, which everyone danced to at parties. They still do. And we were better than that because we were real R&B players so among the things I could say we did well was Stones covers.

“At the time I wasn’t much of a singer, but I had listened to Michael Jagger fairly fucking carefully in the same way I had Lowell George. Our best originals were also Stones knockoffs. Bill [Lake] was good at that. Bill played with Rough Justice a couple of times. We recorded one of his songs [‘Texas Revenge’] for a Radio Windy anthology [1979’s Homegrown] and if the band had gone on I would have looked for more of his songs to do.

“We had a song called ‘Second Skin’. Nowadays when I listen to old Rough Justice tapes – I’ve got one rough cassette recording version – I first played it by mistake one day. I thought ‘What the fuck is this, that’s a good song’ – it was bloody Rough Justice playing a Bill Lake song.

“Tony Backhouse (guitar, vocals) played with us towards the end and we played quite a few of his songs because by that stage the penny had dropped. If we were to survive I had to do a lot more original songs. What Peter and I wrote together was too elaborate. We did have two good originals – one was an instrumental.

“But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself. We started off with Simon Page. The band was going okay, but it became clear that although Simon was a great player, he had a damaged back and he played a wooden piano and the rest of the band carried Simon’s piano, which he couldn’t. He was an out and out pop guy. He was provincial, from New Plymouth. His culture was quite different.

“Another thing about the early band is Simon did play a bit of sax, and he played flute. Because I’d always wanted to take risks with being a borderline jazz-rock band as well as an R&B band as well as a funkadelic band. There were quite a few ways in which Rough Justice referenced Mammal as an earlier step in a similar process and once again [it was] Wellington funkadelic where the funk part of the delic was an afterthought.”

“The rest of the guys in Rough Justice were kind of academic. They were people who’d done really well at university or would have if they’d stayed there. I had been a university lecturer. Peter was kind of outsider highbrow. He listened to John Williams and his guitar tastes were very widespread. If Peter had been born ten years earlier he’d have been a classical guitarist and done quite well, I’d say.

“He had an outsider consciousness as well. His art, his drawing is fantastic. I admired the boldness of his imagination. He could do a gibbon like you could not believe. He was a good singer. When he was in his extrovert mode, some of his guitar playing was communicated in a supra-musical way. He could make it talk, but only in very strange languages."

Rough Justice at Wellington's Last Resort: Stephen Jessup, Mike Gubb, Peter Boyd, Rick Bryant, Nick Bollinger and Peter Kennedy

“We did quite well for a while with Simon, but to put it bluntly the other guys didn’t like him. It was a personality clash. He must have felt very marginalised because he had no mates in the band. We were civilised. We weren’t cruel. We didn’t bully the bastard. If anything he bullied us all by himself.

“He went and once we got Mike Gubb in [on keyboards, organ], everything changed. He was developing very fast. He’d always been really good. I tried to get him in Mammal. I was aware of him coming on as a sixteen-year-old. Our parents were friends. His sister was my Dad’s secretary. I would hear from his sister, and my mother from his mother, how he was coming on. He was already in bands and getting gigs.

"We were really into Little Feat, Allen Toussaint, and The Meters. That was the cluster of influences that was good about Rough Justice mark two."

– Rick Bryant

“Once Mike joined the band [in November 1977], a couple of things happened. We got a couple of good originals. Nick was part of the process – but Mike and Martin were into Weather Report and they got a couple of riffs going. We had quite a good instrumental that we called Rough Report, which had extended solos for all in sundry, but Mike mainly. We were really into Little Feat, Allen Toussaint, and The Meters. That was the cluster of influences that was good about Rough Justice mark two.”

In the following two years, you’d find Rough Justice in country halls and sweaty city pubs, at the new mass festivals including Nambassa and at the Murray McNabb booked Mainstreet Cabaret in central Auckland with Limbs dance company, doing Rolling Stones, Wilson Pickett, Chicago, Blood, Sweat and Tears, Marvin Gaye, Al Green and Otis Redding tunes.

“We had several singers in the band. Nick was a great singer. Peter was a good singer. Mike was an adequate singer. Steve Jessup was an okay singer who became good. Quite early on, Peter Boyd joined up on baritone sax and tenor sax, which was really good because I always wanted horns and he was mates with all the others. He brought something to the band. We never did get a trumpet player, which is what I wanted, but we were stretching it for finances.

“I was looking at ways to change the flavour of the band so we had Denys Mason (The Quincy Conserve, Arkastra) play with us. That was really good move because he was just so good and because every time he got up on stage everyone else in the band would play a little bit better because it would be very rude to play badly when you had such a good musician onstage with you. I wasn’t the only one who felt like that. It lifted everyone’s game because he was so good.

“On the back of mark one’s reputation, Rough Justice mark two got quite a few bookings and they weren’t always happy with us because of the difference in the band. They expected Mike Farrell. They expected Little Feat. But it did work in some places, particularly Auckland and Wellington. And in Auckland by then the gigs were at The Windsor Castle, which worked well for Rough Justice.

“We were quite early in the history of The Gluepot. I think Hello Sailor might have been there once before. It worked really well us. It always worked well for Rough Justice mark two. You’d play Wednesday to Saturday. Later on it was often Thursday to Saturday. Wednesday didn’t work so well.

“In Wellington it would have been the Cricketers. The Last Resort worked really well too. We did okay at the Hamilton venue, the Hillcrest, which was where Rough Justice mark one had done really well. But they accepted Rough Justice mark two even though it was so different. Once we got Mike Gubb in the band, all the serious music consumers realised that things were special.”

Rough Justice also played shows at Auckland cafés The Island of Real and Last Resort, at Christchurch’s Dux De Lux, and within the “underground” circuit.

“The underground circuit was people running clubs unofficially. I wouldn’t have said that Island of Real or Last Resort were underground though. The underground would really have been more like when Rough Justice went to the West Coast and played little country halls. By that stage Graeme [Nesbitt] was out of the picture and we were doing it all ourselves.

“The West Coast was a couple of local guys – sort of varsity dropouts who’d gone there to be hippies and wanted to be hippie rock promoters – even then we’d do the odd party on a commune or at a country hall close to a cluster of communes like Colville or Barrytown or Blackball. Places that we knew there was a guaranteed hippie constituency or audience. Quite a few of these people were people I’d been to university with. So the underground thing would certainly have been our deliberate attempt to go to the hippies where they lived in the deep countryside.

“I loved it. It was part of my ideology and still is. To some extent what I call my ideology was our ideology. With Rough Justice mark two there was quite a strong left wing consciousness. It was the politics of the time of course and also of our cultures as individuals.

"For instance, Rough Justice mark two did a feminist pro-abortion concert benefit in the Wellington Town Hall. I‘m pretty sure we were the only regular rock band to play – there may have been a couple of feminist groups play. All our girlfriends were feminists of one kind or another. When Rough Justice walked out onto the stage at Wellington Town Hall, which had about four hundred feminists in it, most of them left the room because the stage was occupied by men. It made no difference that some of us had incurred personal unpopularity with our families by supporting this cause. That was an ironic consciousness milestone. It was a really rude thing to do. I have to say we laughed. It didn’t really matter.

“It was mainly pubs though and some of them were god awful. Some of them were indescribably filthy like the Castlecliff in Whanganui or the DB Gladstone in Christchurch, where in all the lavatories there were blood sprays up the walls because there were so many junkies in there injecting in the dunnies.

“I’ve never used IV drugs so I don’t know about this, but it was explained to me that these lines up the walls were people squirting out blood filled syringes. But it wasn’t such a bad place to play. DB Hillsborough was good. That was run by an honest guy, Warren Hoy, but also in those days Jim Wilson. Now Jim’s a good guy, but he had his problems. I never had any quarrel with him as a booker.

“We met interesting and worthwhile people everywhere from every background. I don’t know if I make friends easily but I certainly made friends quickly with all sorts of people who are just personally congenial. I mean rednecks, ultra hippies, rich lawyers with a sense of humour, the odd lunatic right-wingers with a streak of the right stuff, conservative Christians (not many of them). Also, being jailed increases the range of people you meet. I have made friends with some pretty unlikely people.”

Rough Justice mark two worked continuously from late 1977 to July 1979. You’d find them at St Amand Hotel in Tauranga in early June 1978 and the Exchange Tavern in Parnell in late July, playing songs made popular by Aretha Franklin, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Muddy Waters, The Rolling Stones, and a version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad of A Thin Man’.

In September 1978, Rough Justice toured South Island universities and teachers colleges with poet Gary McCormick before kicking on to the Lakeside Hotel in Queenstown and later that month to Christchurch’s Mollett Street and a commune in Takaka. October found them on the West Coast of the South Island and in Nelson, December in Christchurch at Canterbury Court and Quinn’s Post in Upper Hutt, before seeing the new year in at an outdoor concert in Gisborne. The group lingered in the sunny Poverty Bay city for dates at the Sandown early the next year before moving on to the Angus Inn in Hastings.

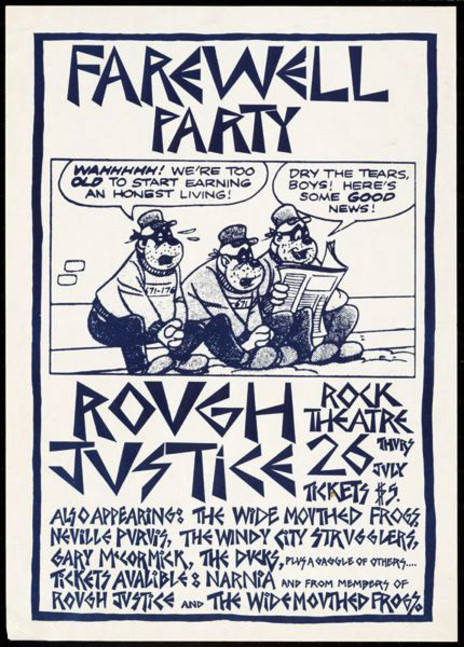

The lineup for Rough Justice's farewell party in July 1979 also included the Wide Mouthed Frogs, Neville Purvis, Gary McCormick, the Ducks (featuring Bill Lake), and the Windy City Strugglers. - NZSA90480, New Zealand Students Arts Council Archives, J C Beaglehole Room, Victoria Unversity of Wellington.

Radio Windy outdoor concerts at Ben Burn Park in Karori and Johnsonville Domain followed in February 1979. Wellington’s Opera House saw them on stage multiple times, first with satirist Neville Purvis (Arthur Baysting) and Alastair Riddell Band, and in April 1979 with Th’ Dudes and Wide Mouthed Frogs on Anzac Day. When Th’ Dudes blew out the gig because of an insufficient PA, Rough Justice played on regardless. Soon after they were back in their second home, Auckland.

Another comprehensive sweep through the South Island in May 1979 saw them in all the main centres and included shows at the Regent Theatre in Greymouth, The Shoreline in Dunedin and DB Rutherford in Nelson after getting stranded in Christchurch for a week when the bus broke down.

A two-page Rip It Up story in May by John Dix had Rough Justice setting up at The Gluepot and at a Sunday afternoon show at Ti Rakau Park in Pakuranga for Radio Hauraki. While in the Queen City they played at The Windsor Castle and Island of Real.

The band at this point was Rick, Peter Boyd and Denys Mason (sax), Nick Bollinger (bass), Mike Gubb (keyboards), Peter Kennedy, and Tony Backhouse, who joined only two weeks earlier from Spats. Dix noted that they’d appeared on Radio With Pictures and Ready To Roll (performing The Rolling Stones’ ‘Beast of Burden’) and were 2ZM’s Band of the Month for May. There were memorable shows in June 1979 with Limbs dance troupe at Mainstreet, Auckland, after Rick had seen them at the Nambassa Festival and got talking.

Rough Justice called it quits on July 24 1979, with a Wellington concert featuring Wide Mouthed Frogs, Neville Purvis, Windy City Strugglers, Gary McCormick and The Ducks. A brief one-show reprise in January 1980 at Brown Trout Festival in Norsewood followed. But that was it.

Nick Bollinger and Tony Backhouse, Brown Trout Festival, Dannevirke, 1980

Rick Bryant: “I moved to Auckland because my girlfriend was going to art school. Rough Justice had finished sometime before mainly because Mike Gubb had decided to go to Australia to go to the Sydney Conservatory of Music. As soon as he decided that, the drummer and the baritone player said, ‘We’re going to do that too.’ I must have been a bit disheartened about things because I just didn’t think about getting another band straight away.”

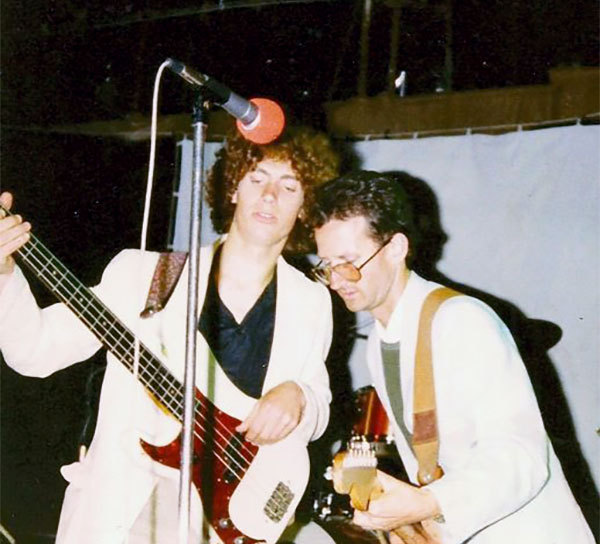

Mike Gubb and Rick Bryant at Wellington's Rock Theatre, 1979 - Mike Gubb collection. Photo by Mathew McKee.

In early January 2014, the old gang assembled again (without Peter Kennedy who was living in Switzerland) for shows in Napier, Auckland and Wellington. In late 2016, Nick Bollinger's memoir Goneville (Awa Press) concentrated heavily on his time in Rough Justice. The book is dedicated to Rick Bryant.