A field somewhere south of Auckland

Date: January 6, 1973

Place: A farm field in Ngāruawāhia

Event: The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival

This was not an auspicious introduction to the group that would become New Zealand's first international rock success story. Split Ends, as they were then called, took to the festival stage to the deafening silence of apathy. Festival promoter Barry Coburn (later to become Split Enz’s manager) had been impressed enough by the fledgling group’s brief set at Levi’s Saloon in Auckland the previous month (10 December 1972) that he gave them a prime early Saturday evening spot at the The Great Ngāruawāhia Music Festival.

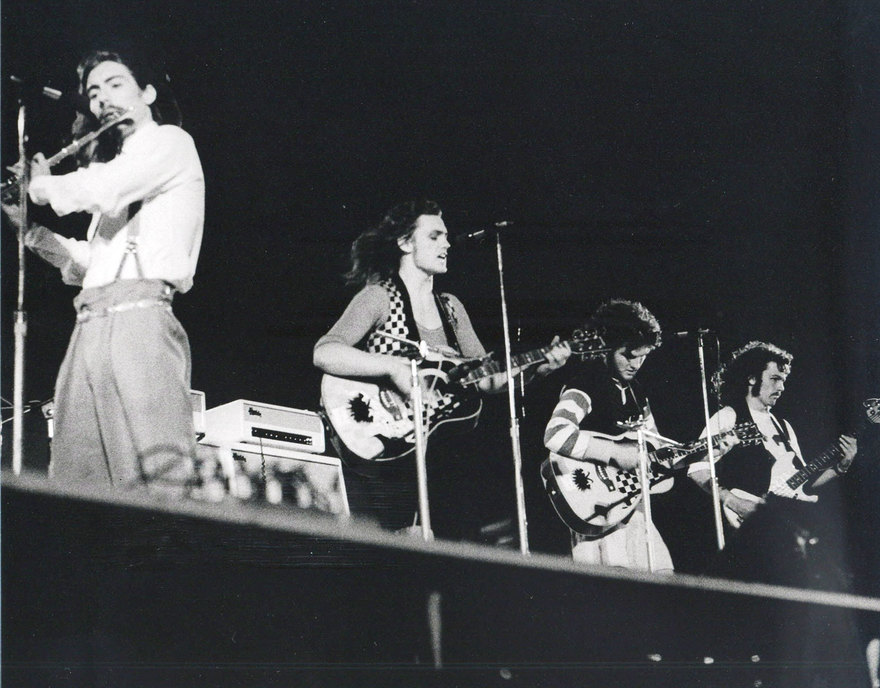

Split Ends at Ngāruawāhia, January 1973 - Mike Howard, Phil Judd, Brian (Tim) Finn, Jonathan Michael Chunn - Photo by Larry Jordan

Very few in the crowd knew of Split Ends, and they were not in a tolerant mood. Most were getting primed to catch blues-rock heroes The La De Da’s and the biggest act at Ngāruawāhia, heavy metal pioneers Black Sabbath, who were due to crank up the decibel level later that night. A bunch of unknowns delivering quirky melodies via such un-rock and roll instrumentation as violin, flute and mandolin was not what the crowd had in mind as an aural appetiser.

In his Split Enz memoir Stranger Than Fiction, Mike Chunn estimated “there were 18,000 people on the site and 17,896 had never heard of us. Split Ends walked on stage at 8pm to a restless crowd that failed to acknowledge their arrival.” Chunn cites the set list as comprising ‘Split Ends’, ‘Under The Wheel’, ‘For You’, ‘Lovey Dovey’, ‘Spellbound’ and ‘129’, after which they were instructed to leave the stage as the show was running behind schedule. A short and far from sweet experience.

Memories of my first exposure to Split Ends (Enz) at the festival are naturally a mite fuzzy after 40 years. Suffice to say, from a vantage point close to the stage, I was a little underwhelmed, although I detected enough potential to decide to give them another chance, under better circumstances. Performing in daylight in a rural field was hardly the ideal setting for a group intent on exploring dark lyrical themes in a theatrical style.

If you’d told me then that I would see this band perform eight or nine times in three continents over the next decade, I’d likely have accused you of over-indulgence in the chemicals that were floating freely around the festival grounds.

A chance to see the band in more favourable circumstances came along just a few months later, when Split Ends were chosen as the support act for a New Zealand tour by John Mayall. In retrospect, it was a bizarre pairing to have young art-rockers open for the godfather of British blues. Back then, however, NZ visits by the bigger names in British and American rock were relatively rare, whereas blues artists like Mayall, Muddy Waters, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee found a welcoming audience. Opportunities for young NZ bands to play shows other than in the pubs or for drunk university students were few and far between, so it’s no surprise Split Ends grabbed the chance.

Writing letters to my friends telling them all about Split Ends

At the Christchurch gig I caught in April 1973, Split Ends fared far better than at Ngāruawāhia, and I remember being impressed at the progress they’d made in just a short time. The hard to keep up with personnel changes that were to become a constant in Split Enz’s career had already begun, as this line-up saw Miles Golding and Mike Howard replaced by Wally Wilkinson and Geoff Chunn, joining the nucleus of Brian (later Tim) Finn, Phil Judd and Mike Chunn.

At the urging of Barry Coburn, an invigorated Split Ends entered television talent quest New Faces, recording ‘129’ for the occasion. After winning their heat, they came up with another number ‘Sweet Talking Spoon Song’ for the final. The fact that they were placed second to last in the final should not have come as a surprise, given the decidedly mainstream bent of the show and its audience. Still, the exposure was valuable, and it led to the band getting a 30-minute special on New Zealand television.

New Zealand’s first global pop success story made one of its earliest screen appearances on this TV talent quest. The episodes are no longer preserved, but a family friend of the Finns pointed his Super 8 camera at the television screen. The clips are combined with the band’s memories from 2005 radio documentary Enzology. Split Ends (the ‘z’ came later) competed in the 18 November heat with ‘129’, and a week later in the final, miming ‘Sweet Talking Spoon Song’. They lost to Wellington's Bulldogs Allstar Goodtime Band, with Phil Warren judging the lads “too clever”.

My next exposure to them was at the first of the now-legendary Buck-A-Head concerts in Auckland, presented by Radio Hauraki. Staged on May 12, 1974, it drew a full house of 1,200 to His Majesty’s Theatre, and was a stunning success. The band’s growing sense of confidence was on vivid display, as was the heightened theatrical component to their performance. Stage props and sound effects punctuated Split Enz’s musically dramatic material in compelling fashion. The enigmatic and stage fright-suffering Phil Judd did not perform with the band, but took part in the theatrics, dashing across the stage in a straitjacket and with a bandaged head, pursued by Geoffrey Crombie, playing a psychiatrist. ‘Stranger Than Fiction’ indeed.

“The Split Enz concert may well go down in history as one of local rock music's major events.” – Roger Jarrett, Hot Licks

In his book, Mike Chunn recalls that “we walked off stage completely liberated.” This scribe was suitably impressed, as was Hot Licks editor Roger Jarrett. In a magazine editorial, he wrote, “The Split Enz concert may well go down in history as one of local rock music’s major events.” In January 1975, Jarrett, a little prophetically, dubbed Split Enz “the finest band New Zealand has ever seen.”

More Enz-headlining Buck-A-Head concerts continued through the year, while the busy revolving door of members leaving and joining also continued. Recent arrival Eddie Rayner had quickly acclimatised, but Rob Gillies and Geoff Chunn left in July 1974. Paul Crowther entered as the new drummer and Crombie joined the fold as spoons player extraordinaire.

Australia, Mushroom Records and Mental Notes

Early 1975 saw another successful university tour up and down the country (I caught their Wellington gig), followed by an initial foray across the Tasman. They made their first appearance on Australian television on the ABC music programme GTK.

By this stage, Split Enz’s growing and enthusiastic fan base was eager for recorded music beyond the batch of singles they’d released. Thankfully, a deal inked with Mushroom Records in Australia led to the recording of Mental Notes in Sydney in May 1975. Upon its release two months later, Mental Notes did crack the New Zealand Top 40 sales chart (peaking at No.8). More significantly, it quickly became the soundtrack of chilly student flats around the country, mine included. Here was vivid recorded proof that one of our own could come up with an album every bit as good as those by the hip or popular American and British bands of the day.

Mental Notes was uneasy listening at its best with Phil Judd’s boldly coloured yet quite disturbing cover art an apt indicator of the chamber of mental horrors within. The 10 songs written by Judd (seven in tandem with Tim Finn) were fleshed out by a Split Enz now numbering seven members). The potential the band had shown in performance was now fulfilled in full cinematic splendour. The best album ever by a New Zealand artist or group up to that point? Gets my vote.

Then to London

When Split Enz flew to London in April 1976, their New Zealand fans were hopeful that they could indeed make an impact there. In this most competitive of music markets, coming from New Zealand was of no tangible advantage, except for perhaps minor curiosity value. With the stakes high, Split Enz began working with Roxy Music guitarist Phil Manzanera, an admirer of the group. Split Enz had not been completely pleased with the sound of Mental Notes, so with Manzanera in the production seat, they planned to re-record the tracks, adding some new songs, and release that as their Northern Hemisphere debut album.

Signing a record deal with Chrysalis Records shortly after their arrival boosted band hopes and sessions with Manzanera went smoothly. In an interview with Alastair Dougal that appeared in the June 1977 issue of Rip It Up, Mike Chunn recalled that, “on the whole, everybody felt pretty good about the album.” He had one concern – “there’s quite a variety in style of songs because we were playing ones that had been written over a long period, so there were obvious stylistic differences. In America, particularly, we found a backlash against this. They thought we should have had a more uniform sound.”

Upon its release in the UK on August 9, 1976, this new version of Mental Notes notched some positive reviews in the ever fickle but then vitally important English music press. “Compulsively droll humour and exacting musicianship,” wrote NME, while Melody Maker’s Alan Jones wrote, “Split Enz may be the most intriguing combo to hit the rock circuit since Roxy Music first swanned onto a stage in 1972.” Of course, the band’s NZ origins did spark misguided attempts at humour, with the headline for a full-page feature in NME referring to “Maoris” and “psychedelia in the colonies”.

Not that instant stardom was to come knocking for the band. Split Enz did their part by gigging constantly in the UK, including as support act for Lindisfarne spinoff Jack The Lad. In a minor way, I did what I could to boost awareness of the band in Montreal on a visit there in November 1976. I wrote a feature story on “Rock Down Under” for the city’s biggest daily paper, The Montreal Star; and was thrilled that dwarfing photos of The Bee Gees and Olivia Newton-John were individual shots of Eddie Rayner, Phil Judd and Tim Finn, each looking quite psychotic. Phil was bald with bulging made-up eyes, Eddie had an almost normal ’do but big buggy eyes, while Tim sported mime-style makeup and four upside down cones of hair.

After the story appeared, Montreal’s major rock station, CHOM-FM, invited me on to discuss Australasian rock, and I was able to get a track from Mental Notes played. At the time Mental Notes was only available on import in Canada. Given that Quebec, in particular, was very partial to progressive and art-rock bands that represented a missed opportunity there. Happily, four years later Split Enz would become a very popular band in Canada, albeit with a much different line-up and sound.

Split Enz’s initial foray into the USA was hardly a triumphant success. A six-week showcase tour from February 1977 was planned to promote the album, but as Mike Chunn told Rip It Up, “we probably averaged about 20 people a night. There were almost more people on the stage than in the audience on some nights.” The premier casualty of the tour was Phil Judd, who decided to quit the band once it was over. Mike Chunn speculated in his Rip It Up interview that, “He was probably just sick of the whole mindless existence of touring and of being constantly at the mercy of whatever the agency tells you to do.”

Exit Phil Judd and Mike Chunn, enter Neil Finn

You could term the departure of Phil Judd the end of Split Enz Mark I, for he had such a crucial creative impact on the group’s early sound and vision. In his absence, Tim Finn was forced to assume a larger songwriting role, and he rose to the challenge. In June 1977, he told Rip It Up, “After Phil left, Eddie and I did a lot of writing in America [at Tim’s uncle's house in Baltimore]. That was a really important period for me because suddenly I was on my own after being with Phil for so long.”

Noel Crombie and Tim Finn in London 1976/77

1977 was to be a real turning point for Split Enz. In desperate need for a replacement guitarist for Judd, the group looked close to home. On a post-US visit back to NZ, Mike Chunn caught a gig by After Hours, a group including brother Geoff Chunn and one Neil Finn, Tim’s 17-year-old little brother. Chunn was so impressed, he suggested Neil join Split Enz. Pitching the idea to Tim and Eddie Rayner, Mike (as recounted in his book Stranger Than Fiction) said “Guys ... what we need is someone who knows what Split Enz is all about. They may not be the greatest guitar player in the world but then that’s not really what we want. We want someone who is going to be a natural member – someone who can fit in instantly and commit fully. That person, you fools, is Neil Finn.” The rest, as they say, is New Zealand music history.

“If music be the food of love, split enz be the silverware.” – Tim Finn

Chunn himself then left the band, to be replaced by Englishman Nigel Griggs. Thrown in at the deep end, that new line-up soon started gigging around England again and quickly entered the famed Air Studios to work on a new album with Geoff Emerick, one that would emerge as Dizrythmia. A watershed gig for the new line-up came at prestigious London venue Victoria Palace in May 1977.

London in 1977 was a city on fire, musically. The first conflagration of punk was well and truly underway, and this presented something of a challenge for Split Enz. Their sound and image was still a long way from the primal attack of punk, but the great thing about the music-obsessed British market is that it is large enough to accommodate bands in a huge array of styles. The theatricality of Split Enz appealed to a section of that music-loving mass, and the dogged hard work they’d put into the grind of constant gigging was starting to pay off. The so-called Frenz of the Enz fan base was growing, and they helped fill Victoria Palace. Many of them sported makeup and colourful costumes in homage to their musical faves.

This scribe caught the gig, along with a bunch of antipodean pals doing the OE thing in London. We were especially gratified to see that the band had caught on with Brits too, not just homesick Kiwis. The show was a near unqualified success, as Noel Crombie wrote to Mike Chunn shortly after (as included in Stranger Than Fiction). “The Victoria Palace was full and went like a bomb ... Our hard core following has enlarged considerably. Pity we only do one Second Thoughts track.”

Eddie Rayner was similarly thrilled with the show. In the June 1977 issue of Rip It Up he wrote, “This was probably the best gig we’ve ever done here. Split Enz look-alikes are becoming quite ubiquitous and a fan club is in the process of being formed.” In that article, Rayner was quite candid about the group’s new direction.

The band I heard at Victoria Palace was quite radically different to the one seen in New Zealand. Neil was quietly finding his feet in the group, so it was up to Tim to dominate proceedings as a performer, and he was definitely up to the challenge. A good chunk of the set comprised songs that would soon come out on Dizrythmia, and they were far removed from the earlier psycho-dramas by Phil Judd. As Mike Chunn observed, “the new material ... fitted neatly with the ‘new wave’ ethic of short, sharp three-minute songs.” Similarly, Noel Crombie’s eye-catching stage costumes for the band now included some punk touches.

In that same article in Rip It Up, Rayner was quite candid about the group’s new direction. “We made a conscious effort to keep all the new songs down in length (most are three to four minutes) as we are growing ever more conscious of the need for the Enz to have a top-selling single and rule the world!”

“we are growing ever more conscious of the need for the Enz to have a top-selling single and rule the world!” - Eddie Rayner

The release of Dizrythmia was again met generally positively in the Anglo music press. My next exposure to Split Enz came on October 22, 1977, when the band scored a coveted 30-minute slot on Sight and Sound, a live rock concert broadcast on radio and TV in the UK at the prime time of early Saturday evening and with an estimated audience of 10 million people. I reviewed the broadcast for Rip It Up, noting that the band was determined to rise to the occasion. Tim was in top form with his signature witty between-song banter – “If music be the food of love, Split Enz be the silverware,” he quipped, as the band launched into a vigorous version of their new single ‘My Mistake’. Tim Finn also excelled vocally on a set highlight ‘Charlie’, while Noel Crombie’s spoons solo was, as ever, a real crowd-pleaser.

English and European touring went well, but the lack of a hit single was now a serious concern. The highs of 1977 were soon followed by real lows in 1978, a year that would have finished less resilient bands. Split Enz parted ways with Chrysalis, and faced a real financial predicament. The Queen Elizabeth II Arts Council, at the urging of Enz fan Ray Columbus, helped out with a grant.

I See Red

Intriguingly, Phil Judd re-joined Split Enz (a short-lived experiment), and with Neil also developing as a songwriter, the band was firing on all cylinders creatively, if not commercially. The lack of a UK-based record label meant that the next Split Enz record Frenzy was only released in Australasia in February 1979.

Split Enz, Frenzy (Mushroom, 1979). Cover painting by Raewyn Turner, the band's lighting designer.

Frenzy notched significant sales in Australia and New Zealand, while the infectious single ‘I See Red’ (not included on the initial pressing of the album) became a solid hit, especially across the Tasman.

A headlining performance at the Nambassa Festival near Waihi in front of 45,000 appreciative concertgoers kicked the year off in fine fashion. By now, Split Enz were in very real demand as a touring act in Australia, and this helped right their fiscal ship. In between extensive touring, Tim and Neil Finn were writing songs, in both Auckland and Australia, and preparations were being made to work on a new album, with recording time set aside for November.

This was a prolific and important period for the Finns as songwriters, and former comrade Mike Chunn documented this well in Stranger Than Fiction. “Tim had shaken the mantle of his former hero figure [Phil Judd] and walked off into the sunset ready to go it alone. The stylistic changes in the songs clearly indicate that shift. Neil’s writing was also changing. He had found a real knack for the melodic hook and was littering his new songs with short, snappy phrases that logged in the brain instantly.”

Split Enz’s next big creative decision was the choice of producer for their album. The year before, they had encountered a boy wonder English engineer, David Tickle. At just 18, he’d already worked on albums by the likes of The Knack and Blondie, and the band did some initial recording with Tickle in England on songs that were to surface on Frenzy. The group was definitely keen to work with him again. Guess you could say he Tickled their fancy.

Pre-production with Tickle began in Sydney in October 1979, and the results were to be career changing.

A new decade loomed. Split Enz were about to reveal their True Colours.

--