On 19 July 1985, Radio With Pictures filmed a "reggae special" at Victoria University's Union Hall, in conjunction with Radio Active. The bands were Aotearoa, Dread Beat & Blood, and Herbs. Ten months later, with the addition of Ardijah to the bill, this groundbreaking event became a national tour. The 1985 TV special can be viewed above; below is Rip It Up's feature review of the 1986 national tour's final show, published in August that year.

Music From the Long White Cloud

It was Māori Language Week when Ardijah, Aotearoa, Dread Beat & Blood, and Herbs played the last night of their nationwide package tour in Whangārei, on 29 July 1986.

I drove up from Auckland thinking such a landmark tour should be covered. I came away feeling that if there is any mainstream “movement” in New Zealand music that is alive and developing, it is the Māori and Polynesian music of which these four bands, with the Pātea Maori Club, represent the leaders.

It was a disappointment, therefore, to find upon entering the Kensington basketball hall only 400 people inside. (Still, it’s a better percentage than in Auckland, where only 700 ventured out to the Logan Campbell Centre). At the door, the amiable security guards checked for forgeries (there was no visible police presence – and no trouble).

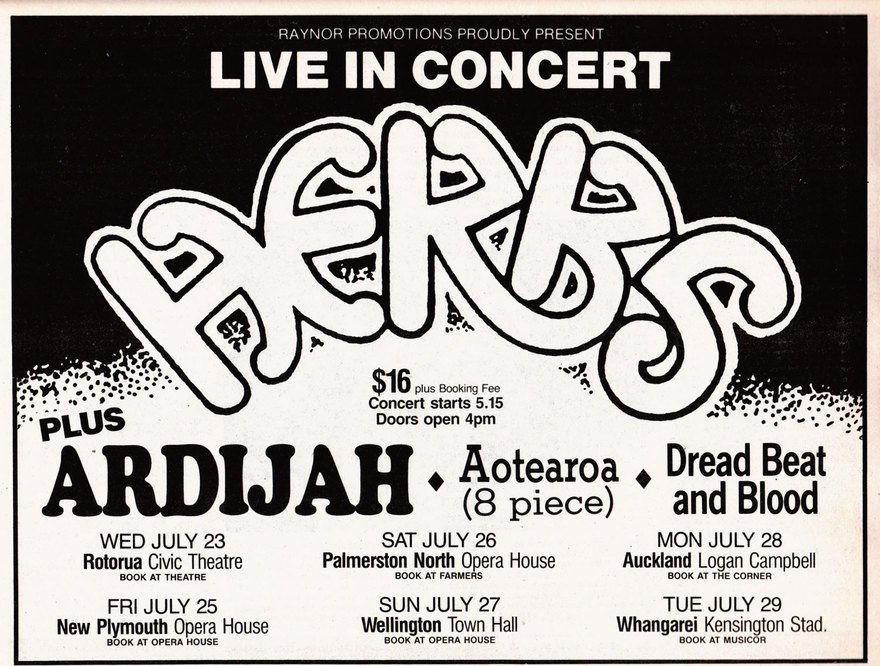

Advertisement for the 1986 national tour by Aotearoa, Dread Beat & Blood, Ardijah, and headliners Herbs. The promoter was Hugh Lynn, a driving force in the renaissance of Māori music in the 1970s and 1980s.

First up at 6.30 sharp was Aotearoa, an eight-piece band from the capital, and unashamedly political. “We’re a band with a message,” said their leader Ngahiwi Apanui as soon as they were on stage. After a long a capella introduction from several members of the band, the smooth, slick sound of Aotearoa emerged: wonderful harmonies, lyrical sax and guitar playing, and a superb, effortless rhythm section.

“This song is very important,” stated Apanui bluntly, and with the opening declamation of ‘Young, Gifted and Black’ a tingle of recognition and revelation went down my spine. Played with a slow, heavy beat, Nina Simone’s anthem didn’t seem like a sentiment from another age, the pre-separatist optimism of the civil rights movement. Instead it felt even more relevant to the present day, and to this overwhelmingly Māori audience in Whangārei:

You are young, gifted and black ...

There’s a world waiting for you

Yours is the quest that’s just begun ...

When you’re young, gifted, and black

Your soul’s intact!

“This is another important song,” we were told and, as the guitarist scratched out the slow reggae rhythm of ‘Maranga Ake Ai’, members of the other bands could be seen taking in the music and the message. “Pacific reggae” Herbs have called it: a rhythm which has been borrowed from another culture to become part of our own. The next song was dedicated to the Kanaks, “the indigenous people of New Caledonia, suffering oppression under the French. This is an expression of unity and support.”

The mood of Aotearoa was more like a rally than a lecture, however: the last song was “all about being positive,” and the refrain said exactly that: “Think positive!” After the example of Aotearoa, it would be impossible not to.

With Dread Beat & Blood, it’s the Jamaican influence rather than the political message that takes the forefront. They have the look and sound of a roots reggae band, and are as technically proficient at their music as Aotearoa are at theirs: musicianship is a point of pride for these bands. Another large group, Dread Beat & Blood has a daunting frontline of four unsmiling, dreadlocked rastas, all in Ray-Ban sunglasses and jungle fatigues.

Their first number cruises along in the trance-like manner of Big Youth: slow, sluggish reggae, as thick as Visco-static oil. The mixer really knows how to get that big, reverberating dub sound to the bass, which helps.

There are cheers and whistles from the audience as they recognise the poppier sound of ‘No Woman, No Cry’ – once again superb harmonies decorate a beautiful melody. An original follows, still with the spare keyboard work, slinky guitar, and high tenor voices characteristic of pure reggae.

After a long, mellow, farewell number, it is “Thank you Whangārei”. Dread Beat & Blood are a testimony to the excellence that can be achieved – without losing an individual character – by coming up through the traditional route of playing covers, before trying out one’s own work on an audience.

This point is hammered home when Ardijah takes the stage. “If you’re looking for a class act, this is it,” says Apanui in his introduction. After an apprenticeship of many years in the clubs of south Auckland, Ardijah has arrived. With their slick production and stylish presentation – plus a single in the Top 20 – they certainly have the air of a “class act” from the big city. The crowd moves up to the stage to have a closer look.

Complete professionals, Ardijah leaves the audience still dancing, and with a message to remember.

All four members are dressed in deep red jackets, white shirts and black ties, making the other bands look dowdy. Like all the bands however, they have their own distinctive sound. Ardijah’s is the sophisticated sound of club funk, provided by the silky voice of Betty-Anne Monga, the delicate tenor of guitarist Tony Nogotautama, Ryan Monga’s plucked Steinberger bass, the upbeat synths of Simon Lynch (the only Pākehā musician on the tour), plus a drum machine and sundry percussion.

Immediately their groove goes right through you with their own song, ‘Joystick’; Betty-Anne adding rhythmic colour (congas, chimes, cymbals) and singing great backing vocals, as electronic wizardry is provided by the synthesiser’s joystick. Then, with ease and grace, she sings ‘Somebody Else’s Guy’, a torch ballad accompanied by Lynch on piano.

Tony provides the on-stage repartee: “This is a song by a group that has been a great influence on us: Rick Dees and his cast of millions ...” No, no, he’s just jiving. It’s ‘Time’ by Mtume, with warm synthesisers, à la Bobby Womack.

Ardijah has a seamless, tireless groove, and that’s the only problem with the band – drum machines never let up, and after laying down some moves for a few songs, you’re worn out, it’s like dancing to a metronome.

‘Time Makes the Wine (Get Stronger)’ follows. It’s a great radio tune, if they played indigineous music in Whangārei (though the concert was sponsored by the local private FM station). The song is also Tony’s guitar showpiece. There are many links between heavy metal and funk, and it’s usually in the guitar solos. With plenty of echo, this was pure Jimi Hendrix: Tony just stopped himself from playing with his teeth.

“D’you wanna party?” During Ardijah’s sign-off song, they introduce the band, and their philosophy. To the nightclubber’s manifesto – “Dancing, and singing / that’s all I ever really want to do” – each band member has a moment in the spotlight. Ryan’s solo, with his back to the audience, is tastefully short.

Complete professionals, Ardijah leaves the audience still dancing, and with a message to remember: “Thank you Whangārei ... We like it here so much, we’ll be back playing on Friday and Saturday.”

Apanui strides back on stage as MC. “For so long they’ve been holding the torch high for Māori and Polynesian music,” he teases. “New Zealand’s premier band: Herbs!”

They enter with dry ice swirling, a beautifully rich, delicate, colourful sound, and a message for all: “Fighting together, Aotearoa, we’re all one. Brotherhood and sisterhood ... together, we’ll stand; together, we’ve got the power.”

It’s the softest of sells, a political theme achieved through musical hypnosis. And since the last time I saw Herbs, the message has been brought home: “We’re fighting for land at Ōrākei / We’re fighting for land in Northland / We’re fighting for power in Parliament ...” All to a cruisy rhythm and lilting melody. ‘French Letter’ is as seductive as a warm bath, and especially pertinent in the week our French visitors flew off to Club Hao after their colonisation, 1985-style. “Nuclear free, yeah! Nuclear free, yeah! Nuclear free, yeah!”

The whole cast was on stage by now, 30 people crowding for a microphone

On ‘Jah’s Son’ (“is coming your way”) keyboardist Tama Lundon, singing to his hometown, is assisted by five others, making six glorious voices at once, with new bass player Charlie Tumahai tossing his head about like a funky rag-doll, radiating happiness as he sings. ‘Long Ago’ is brooding and moving with a karanga opening, and ‘Reggae’s Doing Fine’ is a vocal showpiece, Tumahai showing more cross-pollination as he worries a line, Otis-style, perfecting the pitch with his finger in his ear.

The crowd grooved, relaxed and appreciative, to the familiar Herbs refrains: “Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Azania”, “In the Ghetto-o-o”. But by this time, the audience was a bit worn out: it had been five hours since the concert began. ‘In the Ghetto’ developed into a percussion festival, with timbales, cymbals, toms, congas, and Ryan Monga and Tony Nogotautama from Ardijah sitting in. And on it went, with references to ‘God Defend New Zealand’ cleverly turning into ‘Nuclear Waste’, with its delightful understatement: “Nuclear waste is coming down / And it’s coming down on you ...”

The whole cast was on stage by now, 30 people crowding for a microphone, with Herbs’ lead singer Willie Hona encouraging a young relative to sing with him and breakdance.

“We’d like to end with a tribute to Prince Tui Teka,” said Hona. The song was ‘Hine E Hine’, a Māori ballad which, with ‘Pōkarekare Ana’ and ‘Pō Atarau’ / ‘Now is the Hour’, is familiar to all New Zealanders. It was a moving gesture to a loved and respected Māori entertainer from New Zealand’s most loved and respected band, and a powerful finale to a remarkable tour.

Herbs, Ardijah, Dread Beat & Blood, and Aotearoa, assembled onstage at Whangarei, 29 July 1986. - Simon Lynch collection