C'mon Series One Final Episode, 1967

The New Zealand public’s infatuation with C’mon continued unabated throughout the middle months of the first series. Talks were still being conducted with the ABC, but it was starting to look unlikely after budget cuts had precluded Australian artists from appearing. The poor state of the New Zealand currency against the Australian dollar at the time was also a major factor. A quick look on YouTube at Australian pop shows from the same period reveals dated and unimaginative sets and formats: they were more like our own shows, before C’mon. Cooperation with the NZBC must have been tempting for the ABC, which was in direct competition with other Australian channels.

This left a problem for Moore: with no access to the cream of Australian pop stars, he was starting to run out of suitable local artists to feature each week who could meet the high standards required. It didn’t matter if you were well known or had a new record out, Moore insisted on auditioning all new guest artists. His plight with a shrinking talent pool was not helped with The La De Da’s and Larry’s Rebels being in Australia after appearing in early episodes. The Pleazers had been sentenced to a life ban from the NZBC for being too wild on screen, Ray Columbus was in San Francisco, The Four Fours (later The Human Instinct) and Johnny Devlin were in London, country pop singer Maria Dallas was in Nashville, Jay Epae – who had made a big local impression during 1966 – was also in Australia as were Peter Nelson & The Castaways. Max Merritt and The Meteors and The Dave Miller Set both returned home from Australia for several months during the year, but sadly too late to appear on C’mon. And so the list goes on: illness and voice problems ruled The Chicks out of the first half of the series, and they started to appear regularly during the second half, from 6 May onwards.

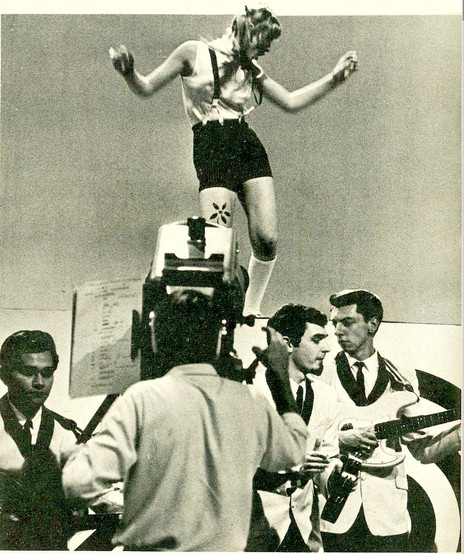

The Chicks on the set on C'mon. - Judy Donaldson collection

To alleviate this problem Moore introduced a New Face segment into the show, starting in the first week of April when popular Auckland blues group The Spectres filled this slot. Phil Warren was instructed to urgently arrange for his Wellington business partner Ken Cooper to audition suitable Wellington groups. Wellington singer Gwynn Owen and Sounds Unlimited appeared twice during the year. Other Wellington groups who made the trip north were The Breakaways and The Avengers, who had just been signed to HMV but were yet to record. The Bitter End from Wellington also made the trek north; they had high expectations of performing their debut single ‘Single Man’ only to be told that they couldn’t perform it because the go-go girls couldn’t dance to it.

Watch Sandy Edmonds sing 'Daylight Saving Time', C'mon Final Episode, 1967

Any of the groups traveling to Auckland to appear on the show were guaranteed several nights of gigs at one of Phil Warren’s inner city clubs. In those days travel expenses and accommodation weren’t part of the deal. Most of the out-of-town bands would travel to Auckland in their vans which required them to start their journey at the beginning of the week so that they were on hand for the various rehearsal sessions. Once in Auckland the bands either slept in the vans or stayed with friends or family.

Opportunity

Of course, a big part of C’mon’s success was Mr Lee Grant, while a large part of Mr Lee Grant’s success was because of C’mon. By the end of 1966, after three years on the scene, Lee’s career was at a stalemate. His manager Dianne Cadwallader convinced the show’s booking agent, Phil Warren, into giving Grant a chance in the pilot.

Mr Lee Grant's biography in the C'mon tour programme, July-August 1967. It notes that Grant has his own weekly radio programme, and that The Avengers TV star Diana Rigg is an honorary member of his fan club

Grant made the most of his chance and was subsequently booked as a regular for the first series. The pilot episode, which featured a six-minute Gene Pitney routine, would have reinforced his vocal ability and power (Pitney was a big inspiration for him).

Grant was an instant and phenomenal success. His first two singles of the year ‘Opportunity’ and ‘Thanks To You’ both reached No.1 and were featured on the show. When The Dave Clark Five single ‘Tabatha Twitchit’ reached No.2 on the New Zealand charts – the only country in the world where it went Top 20 – this was attributed solely to Grant singing it on an early episode of C’mon. (He would record a version of the song for his second album.)

Watch Mr Lee Grant sing 'Thanks To You', C'mon final episode, 1967

In a very early episode Grant and Herma Keil were sitting at the top of the backstage (about two metres high) singing their version of Paul and Barry Ryan’s song ‘Keep It Out Of Sight’, which segued into Grant performing his new single ‘Opportunity’. This required him to jump down from the stage and start singing. After a gentle push from Keil, Grant lost his footing on the polished stage floor. He landed on his backside and briefly disappeared from view, only to rise a nanosecond later smiling and holding his head; without missing a beat he leapt up and carried on. Grant and his switched-on wardrobe – courtesy of His Lordship’s boutique – would have a major influence over teenage fans, intentionally and unintentionally. He recently recalled, “Because of the rapid pace of the show on one occasion I ran out of time for my next shot, and not having enough time to knot my tie I ran back out onto the set and instead of knotting my tie I just let it flop over. The following day about 80 percent of the school kids who wore uniforms showed up at school with unknotted and flopped-over ties which caused a bit of furore.”

The Pleazers’ large fan base was starting to become agitated that their group was banned from appearing on any NZBC show. Their latest and last single ‘Three Cool Cats’ b/w ‘Security’ was being well received, so the group approached the NZBC and was virtually told to get lost. The group’s manager and label boss Eldred Stebbing intervened and pleaded with Moore – whom Eldred knew well – to lift the NZBC ban and let the group appear. But once again the answer was no.

Ray Columbus with the C'mon dancers, 1968

Taking matters into their own hands the group’s substantial fan base from around the country bombarded AKTV2’s office with letters and phone calls of protest. After several weeks of sacks of letters and jammed switchboards, the NZBC relented and invited the group to a meeting to discuss the matter. The meeting went well, with agreement that both sides of their new single were very good and would suit the programme. More importantly, it was agreed that the new-look Pleazers with their shorter hair and mod look would be a welcome addition to C’mon as long as they promised no histrionics and running around the set. The group agreed and made their first appearance on C’mon on the 13th of May, a mere three weeks before they broke up.

As C’mon moved into the last few months of its 1967 season, the ABC finally decided not to purchase the series. Nothing was mentioned, but the non-inclusion of top Australian artists must have had a large bearing on their decision, although pop singers Maggie Joddrell, Ray Brown and English pop star Eden Kane (residing in Australia at the time) all made guest appearances towards the end of the series. ABC was lavish in its praise, but they felt its viewers would ask why ABC had to buy a pop show from New Zealand and not make its own. There was also concern that there were too many references to records being released on particular dates in New Zealand – which could lead to confusion with an Australian audience.

As the nomination period for Loxene Golden Disc finalists loomed, viewers were treated to a smorgasbord of Kiwi artists singing their latest records, including all three of the resident artists who made the final selection: Sandy Edmonds with ‘Daylight Saving Time’, Mr Lee Grant’s ‘Thanks To You’ and The Keil Isles, who released the show’s theme song.

Watch the Chicks in the final episode of C'mon, 1967

Several weeks before the final show, an ambitious 40-day nationwide tour was announced.

At the end of the final episode, an almost sombre Peter Sinclair bid us all a fond “goodbye a go go” as if he was unsure whether or not the series would return. He need not have feared, as within a week of the last show a further series was announced for 1968. Also, to keep the momentum bubbling, the C’mon acts hit the road to meet their fans in person.

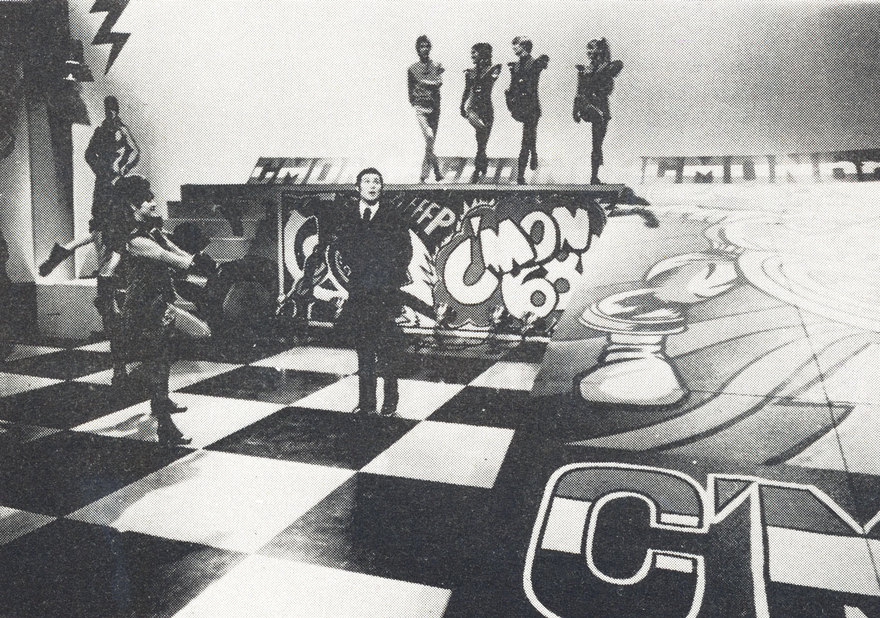

C’mon 68

The second series of C’mon hit New Zealand’s TV screens on 25 May 1968, a full 43 weeks after the end of the previous series. The changes were a-plenty. The show’s original logo – in the Cooper font – was replaced, creating a more switched-on look. The new series was a more manageable 12 weeks as opposed to the 26 weeks of the first series. A new starting time slot of 6.35pm on Saturday evening saw it squeezed between Flipper and The Flying Nun. The new starting time would enable the target teenage audience to watch the show before heading off to their local clubs and dances.

Dorothea Zaymes returned as the choreographer, with a dance troupe of 10, several of whom were in the first series. Art director Anthony Stones was also back, with some new artists including Roy Good. Phil Warren again handled the bookings and Jimmie Sloggett remained as the musical director alongside Bernie Allen.

In a cost-cutting measure to streamline the recording of the backing tracks, drummer Jimmy Hill was replaced by Bruce King. (Hill, one of the great natural feel drummers, didn’t read music.) Fellow ex-Invader Dave Russell joined the band on guitar (if Hill had stayed on, with Billy Karaitiana also on board for the second series, the backing band would have virtually been The Invaders).

The major changes came with the resident artists. Mr Lee Grant was now in the UK and was replaced by the up-and-coming Shane, who had appeared on the previous series as the lead singer of The Pleazers. Also featured was Tommy Ferguson, who had appeared on the first series as lead singer with The Brew. Sandy Edmonds was now in Australia and was replaced by The Chicks. To bolster the roster of regular artists, Phil Warren rang Ray Columbus, who had been in San Francisco for the previous 18 months. After a solid start, Columbus’s career in the US had stalled in recent months and he agreed to come back for the 12-week series, taking over from Herma Keil. (Although Keil had constantly come in for praise during the first season and the tour for his professionalism, there was an underlining feeling that as he had been around since the late 1950s it was time for a new face, even though he was still in his twenties.)

C'mon '68 with Tommy Ferguson

After an audition in front of Moore and Phil Warren, Auckland-based Australian singer Gene Pierson had the inside running to become one of the show’s regulars; with his Italian good looks he was groomed to take over Mr Lee Grant’s mantle. Pierson had been all but assured by Moore and Warren that the job was as good as his. Feeling confident, he invited Moore and Phil to his next gig in a few days’ time.

Pierson’s backing band that night was The Shane Group with lead singer Shane (Hales). After Pierson’s six-song set and with Warren and Moore still in attendance, Shane sensed a golden opportunity and immediately leapt into action and put on the performance of his life. Moore and Warren stayed long enough to be impressed by Shane’s showmanship and vocals and offered him the job instead. Shane originally turned this opportunity down, saying that he couldn’t let his band mates down. Several days later Shane showed up to his band’s practice session and overheard them plotting ways to get rid of him.

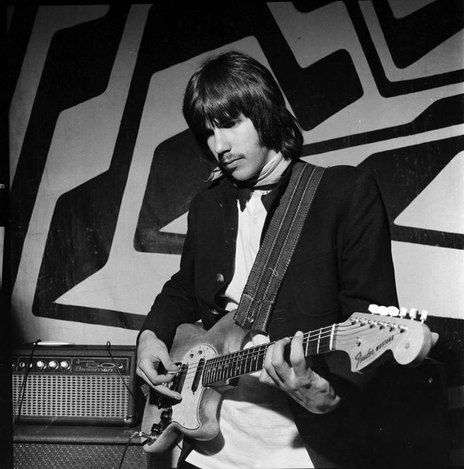

Shane on the NZBC show C'mon - Bruce King Collection

Feeling betrayed, Shane quickly ran to the nearest phone box to contact Phil Warren, not knowing if the C’mon offer was still on the table or not. Warren answered the phone call from an anxious and breathless Shane. He quickly relaxed when Warren assured him that the offer was still open … just. Shane’s previous group the Pleazers came with a reputation, so Moore and Warren sought an assurance from him that any shenanigans and/or unprofessional Pleazer-type activities would not be tolerated. Shane assured them that those heady days were well behind him and he was now totally committed to building his career.

Before the series started Moore revealed that he was well aware that in the eyes of the public the second series of a popular show is rarely as good as the first but he confidently guaranteed that it would be a good show. He also expressed concern about the lack of enterprise shown by any up-and-coming singers: “I advertised in the press for new artists and only received two replies.”

The C'mon band in 1968 - Billy Kristian on the left, with Jimmy Hill, Herma Keil, Roger Skinner and Brian Henderson

Anthony Stones had to come up with a different look. Prior to the launch of the new series he explained: “Pop art is now out of fashion and there isn’t a strong new trend to take over. The last two trends came from the fine arts and they lent themselves very well to pop music programmes. This doesn’t mean that we are devoid of ideas – we will keep the basic design of last year’s series and use elements of nostalgia and personal idiosyncrasies. We will also make more use of glass-painted projection slides and we have been experimenting with ultraviolet light”.

Musically and visually one of the highlights of the year was The Underdogs, introduced by Peter Sinclair as “Our crazy friends from last year: those go-go gurus The Underdogs.” The band then performed a recent Beatles track, ‘The Inner Light’, complete with Lou Rawnsley’s homemade eastern-styled instruments; these included several tambouras and a sitar, all made from pine and plywood. To accentuate the mystic elements of the song, Moore pumped dry ice into the set, which quickly enveloped the band and rendered them almost invisible.

Lou Rawnsley on the 1967 C'mon tour - Louis Rawnsley collection

Some of the members had been smoking pot before the show and they soon started giggling about their situation. Needless to say, Moore wasn’t happy and they never appeared on C’mon again. The following week Truth newspaper ran a story relating to the incident with the headline “NZBC GOES TO POT”.

During July, Johnny Farnham was touring the country with Larry’s Rebels, and both acts appeared on the show. Other acts to appear during the 1968 series were The Fourmyula (performing their debut single ‘Come With Me’ and the Amen Corner song ‘High In The Sky’), The Avengers, Allison Durbin, The Hi-Revving Tongues, The Simple Image, Dizzy Limits, The Dallas Four, Leo de Castro, The Troubled Mind, the Clevedonaires, The Real Thing (whose singer Alan Galbraith featured in the previous series as the lead singer of Sounds Unlimited), Christchurch group The Next Move, and Auckland’s North Shore band The Crying Shame (with a very young Harry Lyon on guitar).

A letter from The Fourmyula's agent, Tom McDonald (who booked most of Wellington at the time) to Phil Warren, pushing the band for the 1968 season of C'mon - Phil Warren Collection

The only turbulence on the series occurred when the go-go girls revealed to the press that they thought that their skirts were getting too short for television. Their pleas to management went unheeded. Several newspapers ran with the story before NZBC released a statement that “longer hemlines were likely – in the near future”.

Watch Tommy Adderley sing The Beatles' 'With A Little Help From My Friends', C'mon final episode, 1967

At the end of C’mon 68, the show once again hit the road for a national tour. All of the show’s regular artists were on the bill: Shane, Ray Columbus, Tommy Ferguson, and The Chicks. Mary Louise and The Troubled Mind featured as the guest artists; The Troubled Mind backed all of the artists as well as performing their own set. The tour opened in Timaru on Monday 19 August, and the show played from Invercargill to Auckland taking in 27 shows over a 28 day period in what was billed as a “Two action-packed hours of non-stop entertainment”; there was only one day off, August 25.

Out of sight of Moore (who never accompanied the tours), it was left to Shane to provide the practical jokes that had been The Underdogs’ responsibility on the previous tour. He recalls, “The go-go girls would be rushing on and off stage for multiple costume changes, they would leave several pairs each of boots at the side of the stage, several times I would break eggs into their boots, you could hear the squelching from the side of the stage.”

On the set of C'mon, with Shane, Suzanne Donaldson (The Chicks), Ray Columbus, Judy Donaldson (The Chicks), Tommy Ferguson, and Ray Woolf. - Judy Donaldson collection

The tour was considered a success and reviews in local papers were generally excellent; with 80 songs performed during the show, there was a general satisfaction of good value. The biggest reaction in most venues was to Ray Columbus performing ‘She’s A Mod’ and ‘Till We Kissed’. Shane also received his share of kudos.

C’mon 69

Before the 1969 series of C’mon began, Moore was asked to produce a live show called C’mon to New Zealand. The show was a live, audio-visual production aimed at the Australian tourist market, and it played in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane. The production featured Ray Columbus, Jacqui James and Yolande Gibson, while Wellington band Cellophane wrote and recorded several adventurous and avant garde pieces of music for the audio-visual section. The cast was invited to perform part of the presentation on the top-rating Bandstand television show, which had four million viewers.

Watch the C'mon To New Zealand tourism promo film, 1969

The third and final season of C’mon saw the return of the behind-the-scenes team: Kevan Moore, Dorothea Zaymes, Anthony Stones, Phil Warren, Jimmie Sloggett, and Bernie Allen. Once again Peter Sinclair fronted the show, in a softer tone and at a more audible pace, which going by various letters to the editor pages was a welcome relief for many older viewers. One newspaper critic noted that Sinclair “has at last been overtaken by maturity and has developed a gratifyingly mellower tone”.

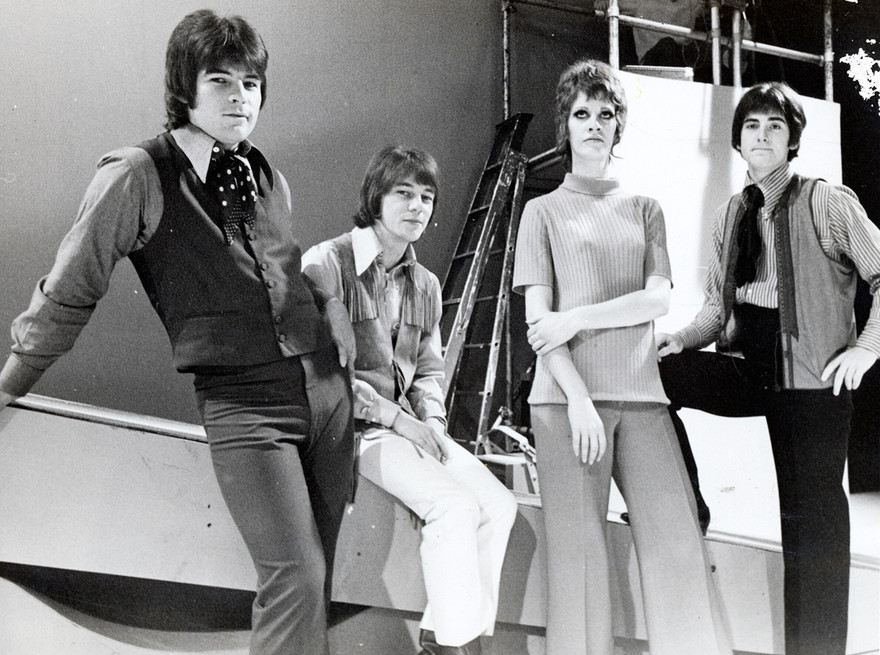

The cats who got the cream on the C'mon '69 set: Larry Morris, Shane, Jacqui James aka Fitzgerald, and Dick Roberts of The Troubled Mind (looking natty in a short tie and long collar).

Shane was the only regular from the previous series to return and was joined by Larry Morris who had recently left Larry’s Rebels; Troubled Mind vocalist Richard (Dick) Roberts was also hired. Jacqui James aka Fitzgerald became the resident female singer, and publicity described her as an “18-year-old red-haired firecracker”. Fitzgerald, whose musical preference was jazz, struggled with the pop sensibilities and daily grind of the show and opted out early in the season. Her place as a regular was taken by The Chicks.

There was also a major change with the show’s time slot: in Auckland, the show now screened live on Wednesday evenings while retaining its Saturday night slot in the other three main centres. In previous years the show had always been screened live in Auckland with the other centres screening recorded versions a week later: at least now it would only be three days before the rest of the country could view it.

C'mon finale, 1968.

The last episode of C’mon 69 screened on 20 August 1969. When it was first launched in 1966, it set the standard for decades for local productions, so it was sad to see the final episode finish on a whimper by comparison. C’mon 69 rarely got a mention in the local press during the last season: a certain sameness had crept into the tried-and-true format and, increasingly, current songs were of a more adult content, making it difficult for the producer to maintain the show’s family appeal.

Kevan Moore already had his sights set on his next production, Happen Inn, which would be launched in 1970. Whereas C’mon captured the 1960s’ pop zeitgeist, by comparison Happen Inn would be aimed more at the middle of the road.

End credits