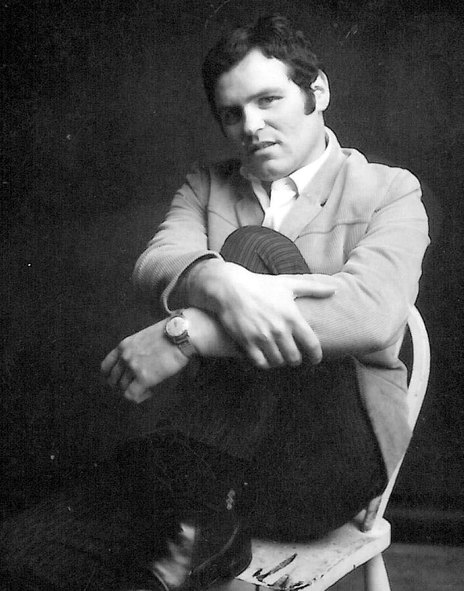

Ferguson didn’t really consider himself a singer, much less a musician, and he had few musical aspirations during his early years in New Zealand. Like Adderley, it was the love of a woman which prompted him to jump ship and he lived in Northland, working at the Portland Cement Works and raising a family. In 1964 he was deported but returned to New Zealand legally soon after.

In 1964 he joined the Astrobeats, who had a Saturday night residency at the Papatoetoe Town Hall, promoted by Phil Warren.

Back in New Zealand, the Ferguson family settled in South Auckland, with Tommy house-painting by day but becoming increasingly interested in a sideline as a singer. In 1964 he joined the Astrobeats, who had a Saturday night residency at the Papatoetoe Town Hall, promoted by Phil Warren.

Warren was impressed with Ferguson and organised a recording session, resulting in the Astrobeats’ sole release, ‘Jenka Rock’/‘Bugle Call Jenka’ on the Allied International label. They disbanded in 1965 and Ferguson joined a new group, sharing lead vocals with Ray Woolf in The Avengers (not to be confused with the Wellington band of the same name).

Ferguson’s stay with The Avengers was brief. In 1966 both he and Ray Woolf became attached to the collective which evolved into The Brew. A single, ‘Bengal Tiger’/‘Tea For Two’, featured Woolf on one side and Ferguson on the other. The Brew, who played an unusual hybrid of styles, was not to Woolf’s taste (“a little out there” he said later) but Tommy slotted in just fine. The Avengers became Ray Woolf and The Avengers and Tommy Ferguson became a full-time member of The Brew.

The Brew featured two colossal talents in American saxophonist Bob Gillett and guitarist Doug Jerebine and Ferguson was well aware of the company he was keeping. “How lucky could I be to do my apprenticeship with two such musical giants, this cheeky little Scotsman?”

The Brew was at the forefront of these changes in New Zealand, dabbling in hallucinogens and adopting a hippie appearance and lifestyle.

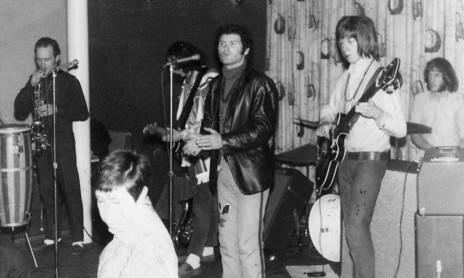

During Ferguson’s tenure with the Brew, the line-up was completed with drummer Trix Willoughby and bassist Puni Solomon (later replaced by Yuk Harrison). It was 1967 and there were big musical and social changes happening around the world. The Brew was at the forefront of these changes in New Zealand, dabbling in hallucinogens and adopting a hippie appearance and lifestyle. Gillett, already regarded as a hipster and beatnik, became something of a guru for the burgeoning movement.

Gillett, such an accomplished musician, was also a radio band leader, producing a weekly live 30-minute programme. Ferguson and the rest of The Brew became part of this 18-piece orchestra. But it was The Brew’s more innovative sounds at Picasso’s which attracted Auckland’s avant garde, the free-form jazz musicians and the more experimental rock bands. Those that dared.

Picasso’s was renowned as the roughest club in town, second home to members of the criminal fraternity and some of Auckland’s toughest street gangs. Once a respected supper club, Picasso’s had launched the career of Ricky May and others but those days were gone – the new owners, well-known to the police, had taken over a club in disrepair, making no attempt to return up-market. The last Auckland nightspot to close (at 4am), musicians would brave the clientele to catch The Brew after their own gigs had finished. Ferguson said later, “We were the only white guys there. There were fights almost every night but they left us alone. Besides, they had a long way to go, I’d seen it all, I came from the hardest city in the world.”

It was a mighty strange band, filled with eccentrics. Jerebine, as well as an ace musician, was a qualified radio technician and he experimented with pick-ups and effects pedals, even constructing an instrument out of a household door and piano strings; Gillett played an amplified sax, and Willoughby’s kit included dustbin lids and paint cans. The band’s repertoire was mostly contemporary songs but Gillett’s arrangements made them barely recognisable and were often nothing more than vehicles for Gillett and Jerebine to stretch out. Ferguson’s voice fitted in perfectly. Jerebine said later, “Tommy has a perfect ear and his voice has a pure harmonic.”

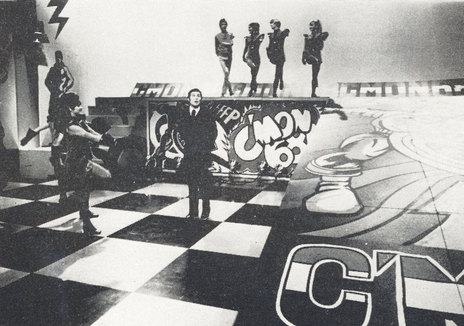

They may have been “out there” but they were serious musicians and when they were contracted to appear on the new C’mon television series, they did the unthinkable. When producer Kevan Moore instructed them to perform ‘(Theme From) The Monkees’, Jerebine point blank refused. They were never invited back. But Tommy Ferguson was.

In 1968, recommended by Phil Warren, he was contracted as a resident singer on C’Mon and was included on the associated national package tour.

Ferguson spent a year with The Brew before joining the resident band at Mojo’s nightclub with Claude Papesch, Dave Russell and Bruno Lawrence and in 1968, recommended by Phil Warren, he was contracted as a resident singer on C’mon and was included on the associated national package tour.

Kevan Moore was much impressed by Ferguson (“he’s rugged and dynamic and he can sing!,” he told the NZ Listener) and he was contracted as a resident for Happen Inn, the show which replaced C’mon in 1970.

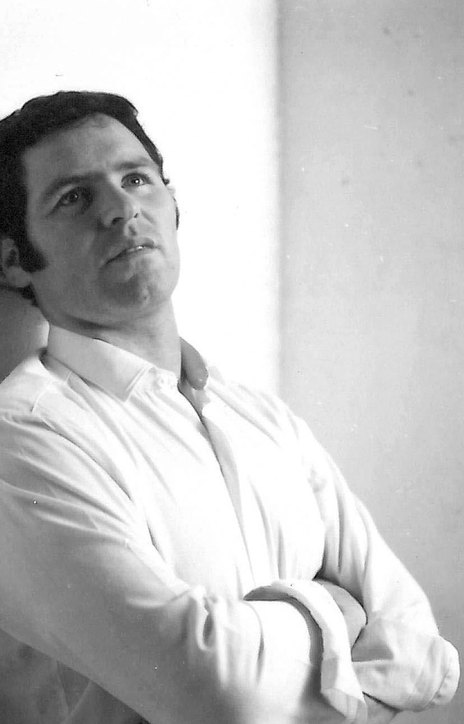

In 1973 came the Tommy Ferguson Goodtime Band with George Barris (guitar), Neil Edwards (bass) and Rick Ball (drums), which evolved into a seven or eight-piece with horns and up to three featured singers (including Sonny Day and Josie Rika). Richard Holden, National Entertainment Manager at Lion Breweries, was greatly impressed, contracting the band for a three-month national tour. At tour’s end, coupled with Dragon, the Tommy Ferguson Goodtime Band performed a 15-minute set for the new TVNZ music series Free Ride.

In 1976 Ferguson departed (the band continued as Rainbow), working the Auckland traps as a guest vocalist. With a family to support, he always retained a nine-to-five job as a tradesman painter and decorator and in 1978 he shifted the family to Hamilton to start his own painting business. The owners of Lady Hamilton’s invited him to form a resident band, which filled the nightclub four nights a week but, following a payment dispute, Ferguson opened his own nightclub, Gasworks, with a band featuring himself, guitarist Kipa Royal, bassist Jackie Parama and drummer Ken Williams.

In the 1990s Ferguson divided his time between Auckland and his adopted home in the Hokianga. There were regular floor shows in city nightspots, sporadic television appearances, and occasional full-time bands for club and pub residencies. A business relationship with Alan Jansson, the Module 8 Recording Studio, turned sour and a proposed single for Warner Music, ‘Pacific Cowboys’, went unreleased (Ferguson citing his own unhappiness with the final product).

More recently, Ferguson played a large part in convincing the reclusive Doug Jerebine to return to music after a 40-year hiatus. Tommy Ferguson still performs on occasion and he has been recording (with Jerebine) the catalogue of compositions he has built up over the years, mostly songs with a social conscience. Ferguson’s rare public performances feature some of NZ’s finest musicians, including Ricky Ball, Garry Clarke, Neil Edwards, Yuk Harrison, Doug Jerebine, Billy Kristian and Lisle Kinney.

Tommy Ferguson has never enjoyed a hit record but he has a long time reputation as an exuberant showman and crowd-pleaser and remains one of the most colourful characters in NZ rock.