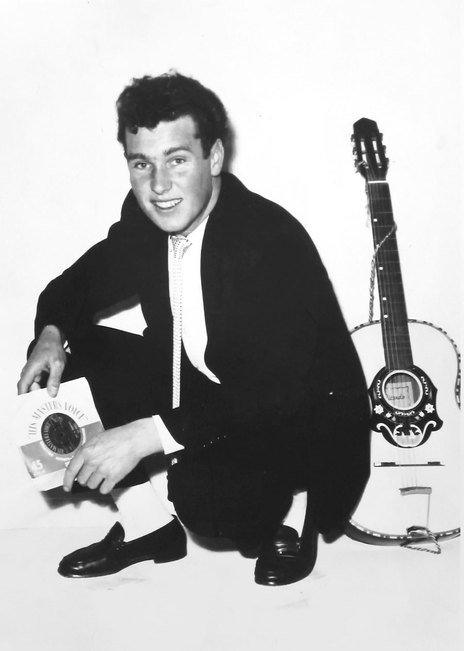

Maxwell James Merritt was born in Christchurch on April 30, 1941. At age 12 he was taking guitar lessons with no great enthusiasm, impatient to replicate the hit songs of the day without having to endure endless renditions of 'Home On The Range'. The boredom was sorted when his teacher, a second-hand dealer, was imprisoned for receiving stolen property.

Bitten by the rock and roll bug

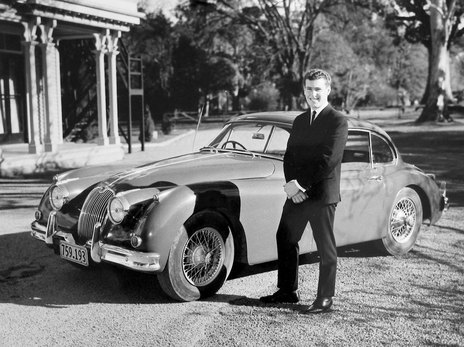

Leaving school at 15 to serve as an apprentice bricklayer with his father, his interest in the guitar waned until 1956 when he heard 'Rock Around The Clock', 'Heartbreak Hotel', 'Be Bop A Lula' etc. He purchased an electric guitar and with cousin Tony Merritt on guitar and Davey Burns on drums, they attempted to play Elvis, Haley, Little Richard. It didn't work out, but Max had the bug.

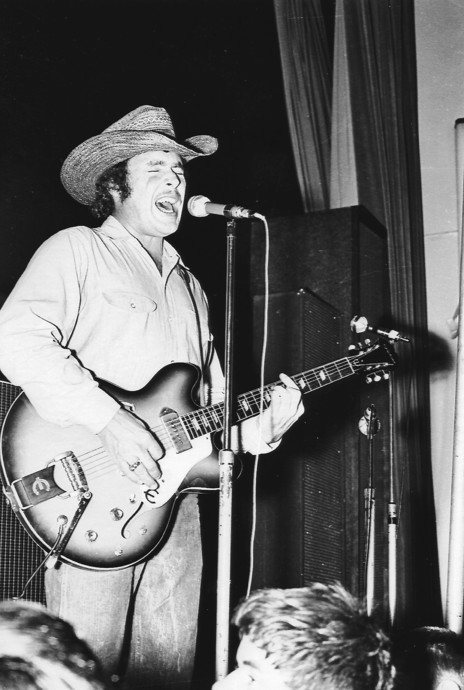

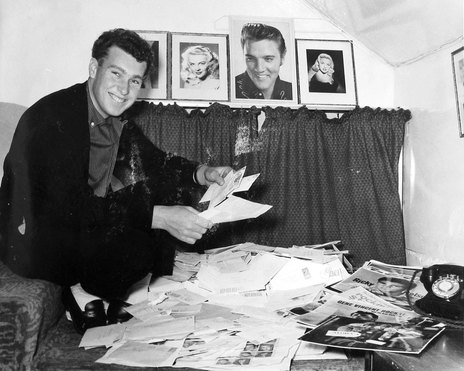

Merritt was a teenage bricklayer when he first heard ‘Rock Around the Clock’.

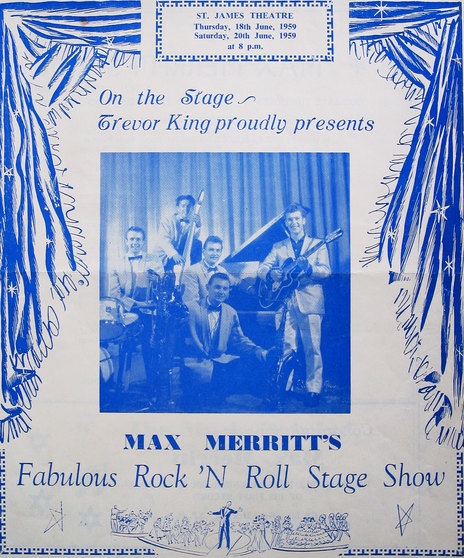

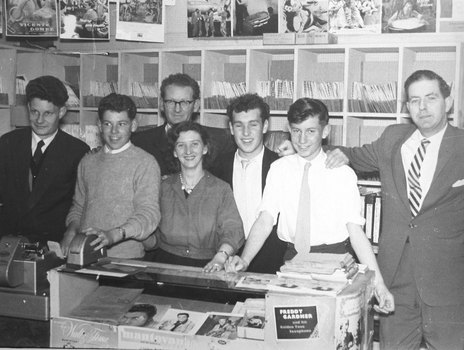

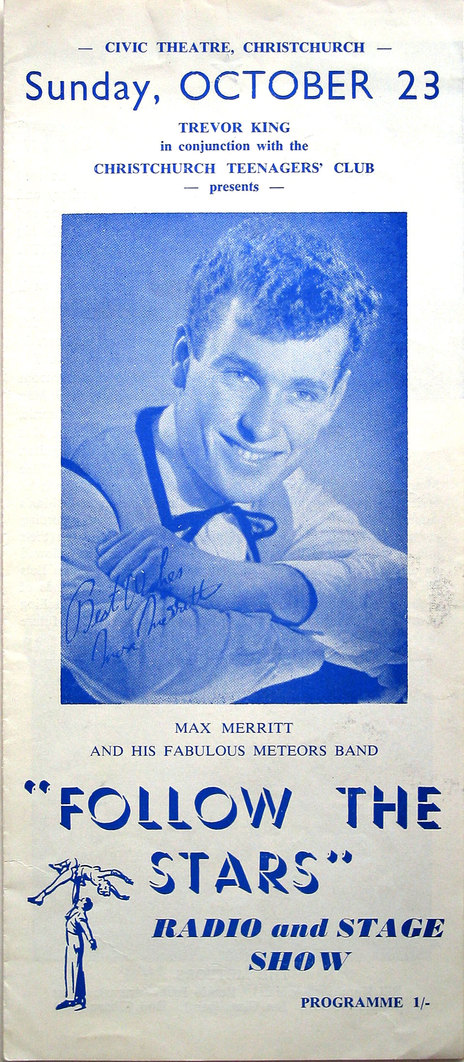

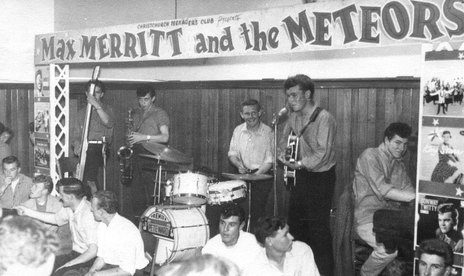

In 1957 Christchurch authorities were alarmed about a growing number of incidents associated with rock and roll. A particular worry was the hundreds of teens who congregated every Sunday afternoon in The Square. A meeting of concerned citizens was arranged by theatre manager Trevor King, which was attended by Jim and Ilene Merritt and their 15-year old son Max. The result was The Teenage Club, held 2pm to 6pm every Sunday and managed by King and the Merritts, which is where Max Merritt and the Meteors evolved.

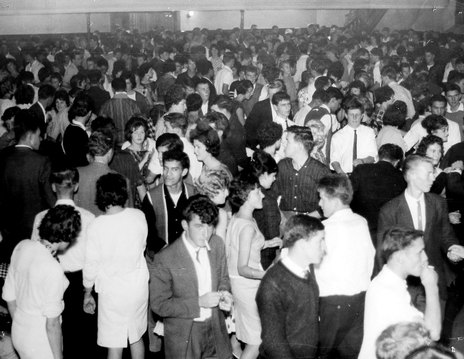

The Teenage Club

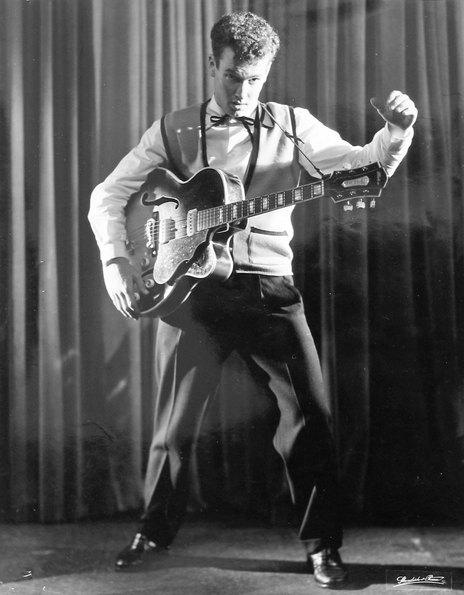

The Teenage Club was Christchurch’s first rock and roll venue and Max Merritt and The Meteors were the city’s first rock and roll band. “We started off at the Winton Street Hall,” Merritt remembers, “but we were evicted after complaints about noise and kids hanging around outside. I think the hall in England Street was next and the same thing happened there. We went through five or six venues before the Railway Hall. It was a bit like Footloose – all the elders and church folk were agin us!”

Despite the opposition, the club flourished – at its peak, it boasted 1,200 members and by the end of 1957 it was attracting weekly crowds of 800 jiving teenagers. Max Merritt became a local legend and a reluctant spokesperson for the rock and roll generation.

To accommodate demand, Merritt added Wednesday and Saturday night dances at other Christchurch halls, notably the Hibernian, a well-known trouble spot. Merritt: “There’d be Māori boys in one corner and Samoans in another. A local bodgy gang, the Demo Boys, were generally hanging around and there were seamen over from Lyttelton. It got sure got volatile at times!”

To avoid eviction, a solution arrived with guitarist Geoff Cox, a South Island boxing champion. Whenever a fight erupted, Cox would down his guitar, jump into the fray, eject the troublemakers and be back onstage for the last verse.

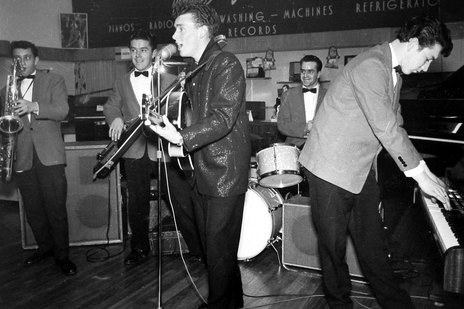

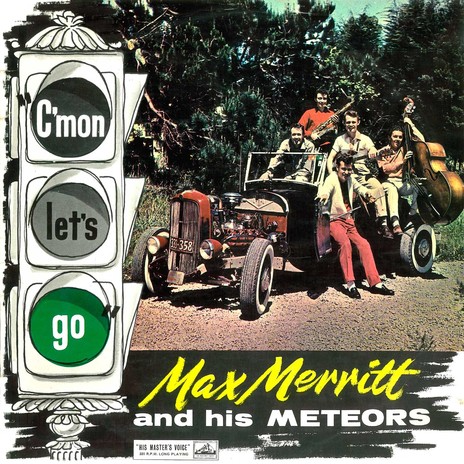

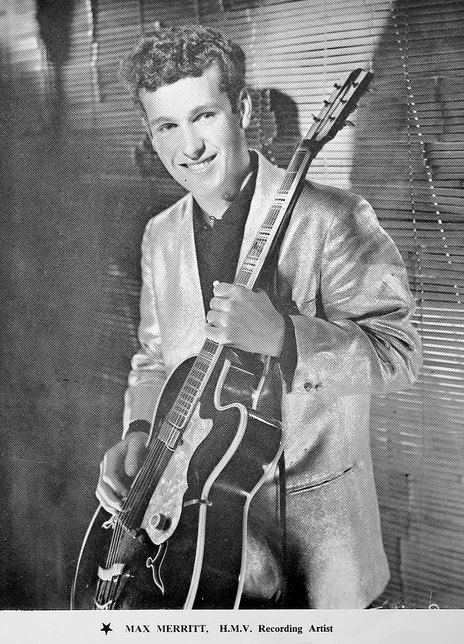

A dozen musicians played in The Meteors between 1957 and 1962, with only Merritt and drummer Pete Sowden as constant members. The band’s recording career began in 1959, and over the next two years HMV released half a dozen singles and a full-length album, C’mon Let’s Go. The first release, ‘Get A Haircut’ (written by Merritt and Teenage Club regular Dick Letussier), was launched at a packed Christchurch record store with hundreds spilling onto the street.

“HMV was hopeless,” Merritt says. “We did everything ourselves, arranging the recordings and promotion, the record stores. We recorded at Keith Robbins’ home studio, and the album was recorded at the 3YA studio and we more or less produced everything ourselves.”

Although Merritt was a proficient songwriter, The Meteors’ repertoire was reliant on covers. Max – “I had a Grundig tape recorder and I’d get home after the Saturday dance around midnight and stay up recording Australian radio stations broadcasting the latest releases. On Sunday night we’d choose the most suitable songs, rehearse them on Monday night and be playing them at the Wednesday dance.”

Another source of material came from American servicemen stationed at Christchurch Airport as part of Operation Deepfreeze, who would bring Max mostly obscure recordings. Not many NZ bands were playing Albert King and Ray Charles in 1960 (Charles’ ‘Hallelujah I Love Her So’ features on The Meteors’ 1960 debut album).

Moving to Auckland

A North Island tour in December 1962 led to the offer of Auckland work. In recognition of The Meteors’ social and charity work, there was a civic farewell at a packed Majestic Theatre, attended by the Mayor and other dignitaries.

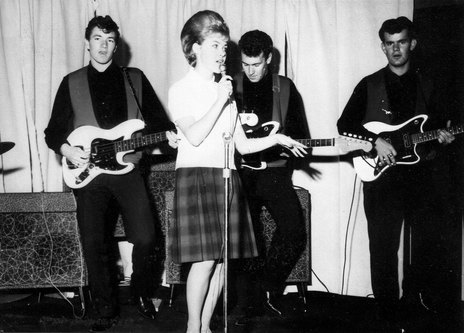

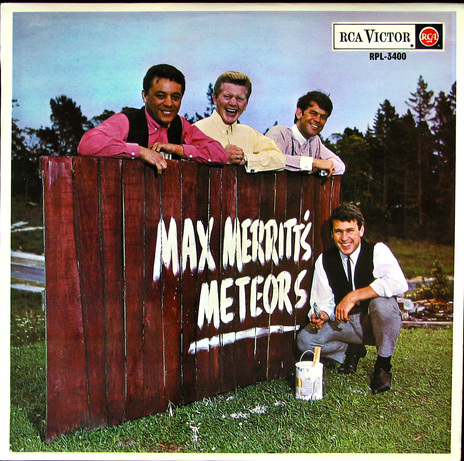

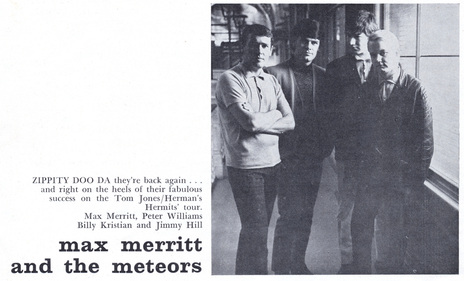

The Meteors arrived in Auckland in March 1963 to kickstart a new venue, The Top 20. The line-up was Merritt and Peter Williams (guitars, vocals), Billy Karaitiana AKA Billy Kristian (bass) and Johnny Dick (drums); Kristian was replaced by Mike Angland after a quick trip to Sydney in September to appear on the Sheb Wooley tour.

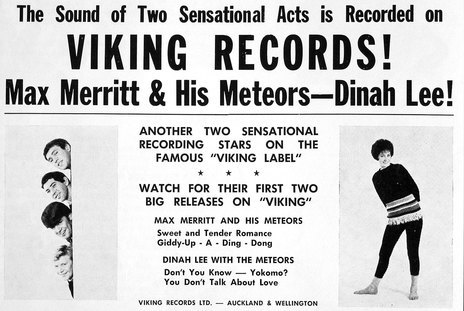

At year’s end, The Meteors became Viking Records’ in-house band, providing the backing for Tommy Adderley's ‘I Just Don’t Understand’, Dinah Lee's ‘Don’t You Know Yockomo?’ and Peter Posa's ‘The White Rabbit’. Sadly, the band’s own Viking releases were poor sellers by comparison. Two 1964 EPs in particular, Giddy Up Max! and Good Golly Max Merritt!, display a raunchy band, suitably rough around the edges, which had successfully made the transition from 1950s rock and roll via Shadows-style instrumentals to the beat boom.

It was around this time that The Meteors earned a sobriquet which became something of a millstone – “musicians’ band”. Indeed, from this point on, Max Merritt and The Meteors would remain a firm favourite of fellow musicians, one of whom was ace Aussie saxophonist, arranger and producer Jimmie Sloggett, a regular guest at the Top 20.

“The Top 20 was open five or six nights a week,” Merritt remembers, “and the weekend hours were killers – 6pm to 2am, with only three minutes off every hour. Sloggett would join us around midnight so the last couple of sets were always hot. Sloggett provided the whiskey and Mikey Leyton, the English singer who worked at the drinks counter, provided the amphetamines. Man, by 2am we were bouncing off the walls!’’

Sydney

In December 1964, new manager Graham Dent secured the band a three-month residency at Sydney’s Rex Hotel. Angland declined to go, replaced by Teddy Toi. 1965 was divided between Sydney and Auckland, where they recorded the Max Merritt’s Meteors album at Stebbings for RCA Records, not Viking. Looking back, Merritt says, “We didn't make a cent out of Viking. I don't even recall receiving a fee for the recording sessions behind Dinah and Tommy and them, and we certainly never received a royalty cheque.”

When billy thorpe filched the Meteors’ rhythm section, this led to The Invaders’ demise.

In Sydney the top Aussie bands were Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs and Ray Brown and the Whispers, joined by NZ's Ray Columbus & The Invaders. When Thorpe's band deserted him over a pay dispute, Thorpe filched The Meteors' rhythm section. Max was convinced that it was a deliberate attempt to sabotage the band. “We were starting to get noticed – it was a great band and Ted and Johnny held it down, a great rhythm section. I've always believed that Thorpie and John Harrigan (Thorpe's manager) were concerned about our growing popularity.”

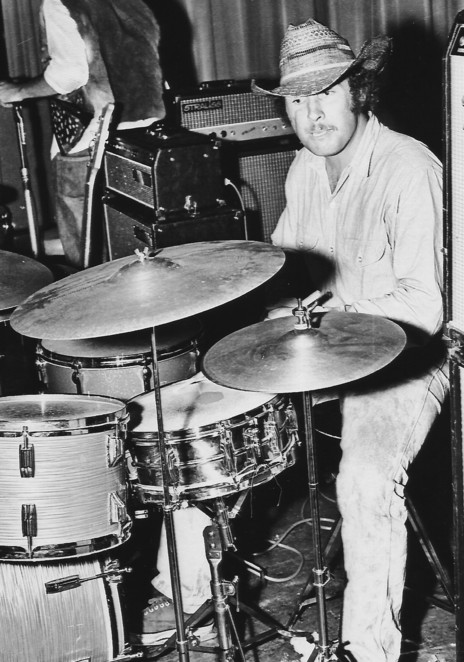

When bassist Billy Kristian and drummer Jimmy Hill of The Invaders heard that The Meteors required a rhythm section, they offered their services, leading to The Invaders’ demise. Hill didn't last long, just enough to record a single for Parlophone ('Zip A Dee Doo Dah'), departing on the eve of a national tour supporting The Rolling Stones after a punch up with Merritt. Bill Fleming was hurriedly pulled in and at the end of the tour Bruno Lawrence was recruited.

Lawrence shared Merritt’s love of black American music and soul music soon dominated the repertoire and in July 1966 a double-sided single, 'Shake'/'I Can't Help Myself' (covers of Sam Cooke and the Four Tops respectively) indicated the band's new direction and provided the band with their first Australian chart entry.

During a New Zealand tour shortly after, The Meteors recorded what became Max’s theme song. ‘Fannie Mae’ was a raw blues and Stateside hit for Buster Brown but a brass-driven rocker as arranged by John Charles at HMV’s Wellington studio. In Christchurch, Mike Rudd, creating waves at the time with his band Chants R&B, was impressed by Merritt’s new musical direction. In 2011, he paid tribute:

I heard that Max and the band were in town

So I picked up my girlfriend and we headed on down

But I wasn’t prepared for such a mighty sound

He was a soul man ...

When he left town he just played rock & roll

But when he came back again he played a whole mess of soul

He laid down the groove, he had total control

He’s a soul man ...

‘Soul Man – A Tribute To Max Merritt’, Spectrum, 2011, words & music by Mike Rudd

Cruising together

Back in Sydney, it was a hard graft. Graham Dent wanted the band to move onto the lucrative cabaret circuit, resisted by Merritt, and in the new year he secured the band a Pacific cruise.

The quintet took to the high seas and, well, it was one alcohol-fuelled party.

Billy Kristian, a tee-totaller, had grown tired of it, and Peter Williams, his role diminishing, had his own plans. Both handed in their notice on the eve of the cruise. At Lawrence’s suggestion, saxophonist Bob Bertles was brought in to bolster the sound. The quintet took to the high seas and, well, it was one alcohol-fuelled party. During the Auckland stopover Bruno took the partying ashore and didn’t make it back. Max played drums on the final leg to Sydney, where Kristian and Williams formally departed. Dent, in frustration, resigned as manager.

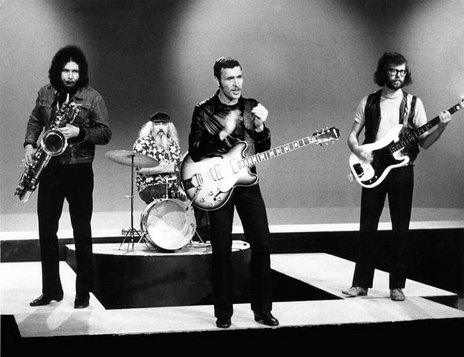

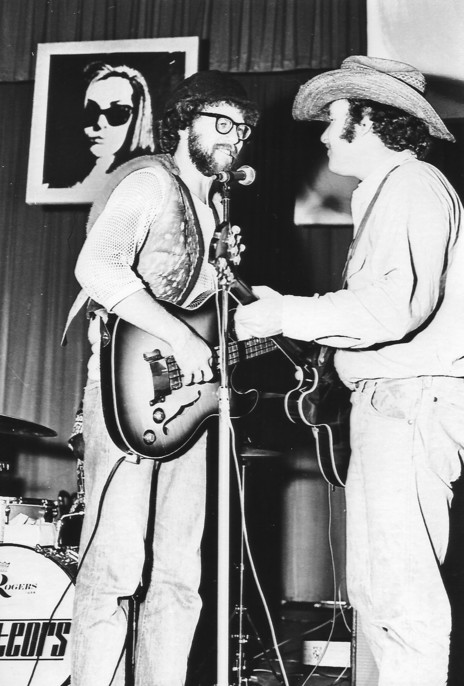

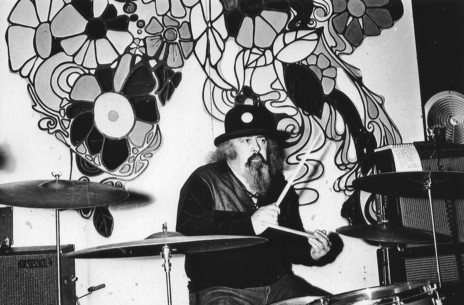

Without a band, Merritt convinced Bertles to stay on. Bertles, in turn, recommended jazz drummer Stewie Speer, and the line-up was completed with John ‘Yuk’ Harrison, recently arrived from Auckland. Harrison had been a journeyman bass player since the early 60s. A renowned party animal, Yuk fitted in very well with the new Meteors.

The accident

The new line-up based themselves in Melbourne but just weeks after the shift south, on June 24, 1967, the band was involved in a head-on collision. All but Yuk received serious injuries – Max lost his right eye, Bertles and Speer both received badly broken legs, among other injuries. It would be 1968 before Max Merritt and The Meteors returned to the stage. But when they did, their fortunes changed.

After their medical ordeals, it was perhaps little wonder that the group earned a reputation as a bunch of outlaws. They took to wearing leather, denim and T-shirts, swizzled alcohol on-stage and didn’t mind their language.

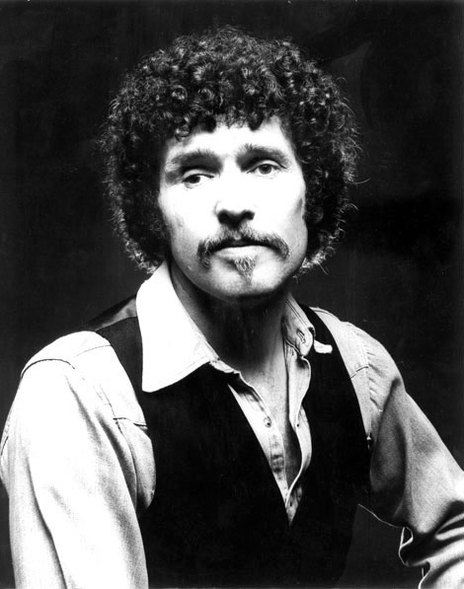

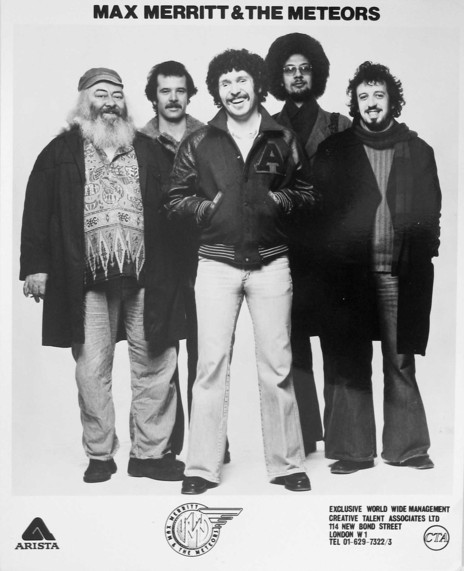

And they looked ... odd. Merritt kept his hair close-cropped at a time when long hair was a mission statement; Speer, a giant of a man, prematurely grey, looking even older than his 40 years; Bertles looked and sounded like what he was – a jazz hipster; and Yuk Harrison looked just like what he was – trouble.

Australia's King of Soul

In 1968 the “musicians’ band” started attracting sell-out crowds and by the end of the year they were reputedly Australia’s highest-paid band. They certainly had the largest repertoire; again reputedly, they could call on 200 songs at any given time, mostly covers but with an increasing number of originals.

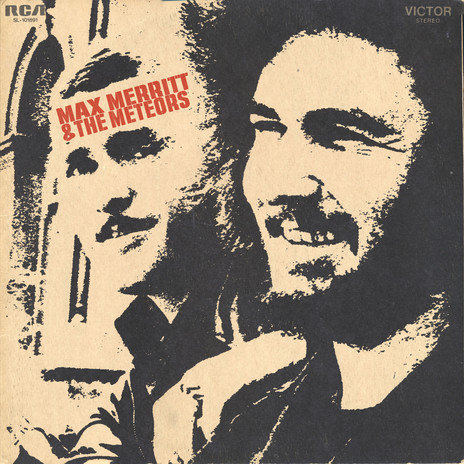

Max Merritt was now Australia’s undisputed King of Soul and in December 1969 RCA released ‘Hey, Western Union Man’, providing Merritt with his biggest hit to date (No.13 on the Australian national charts). In April 1970 came Max Merritt & the Meteors, widely hailed as one of Australia’s watershed albums. It reached No.5 on the Australian album charts.

Unfortunately, by that stage the line-up stability had ended when Yuk was sacked following a drunken set at the Pilgrimage For Pop, Australia’s first Woodstock-type festival. Just days later ex-Invader Dave Russell phoned Max from Auckland, enquiring whether he knew of anyone needing a guitarist – “No, but we need a bass player ... ”

The UK and that song

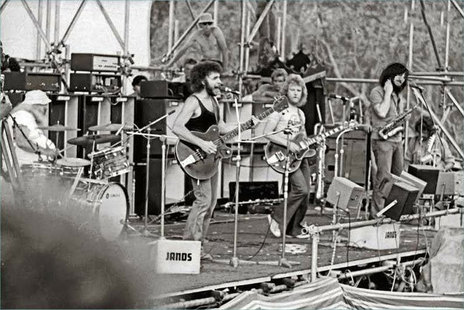

Russell joined the band at a time when Merritt had London in his sights. They arrived in August, leaving behind a second album (Stray Cats) and a four-part series for ABC Television, Max Merritt and The Meteors In Concert, recorded in front of a live audience and augmented by additional horns.

England was a hard slog and The Meteors returned to Australia to headline the first Sunbury Festival in January 1972, followed by a national tour, which they repeated 12 months later.

In 1973 there were signs that the band was making headway with support tours with The Moody Blues, Slade and the post-Morrison Doors, but in 1974 Merritt’s career hit an all-time low when it was discovered that departing manager Peter Raphael had misappropriated band funds. Dave Russell returned down under, Bob Bertles joined top British jazz band Nucleus, and Stewie Speer found work on the London blues/jazz scene. Max Merritt, for the first time since 1962, returned to his trade as a bricklayer.

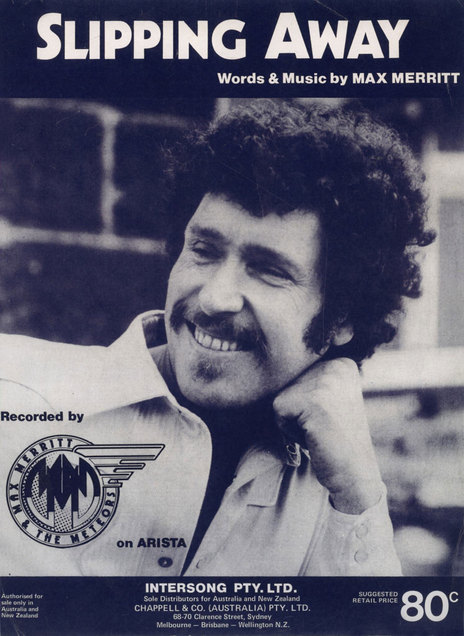

‘Slipping Away’ gave Max Merritt the biggest hit of his career.

In late-74 a new Meteors emerged, Speer back on drums with a band of Brits and Australian expatriates, to produce a new sound, with John Gourd’s slide guitar dominant, playing fewer soul covers and more Merritt compositions. In May 1975 Clive Davis, head of newly-formed Arista Records, signed The Meteors as the label’s only “British” act. ‘A Little Easier’ was released in July and an album of the same followed. The second single was ... that song.

‘Slipping Away’ was released in September 1975, making no impression in Britain but down under it gave Max Merritt the biggest hit of his career, peaking at No.2 in Australia and No.5 in NZ. “That song struck a chord with a lot of people,” Max says, “and I’m very proud of it. It has been very good to me.”

In July 1976, The Meteors toured Australia to promote the second Arista album, Out Of The Blue. The performance at Melbourne’s Dallas Brooks Hall was recorded and later released as the third and final Arista album, Back Home Live.

Back in Britain, though, it was back to the grind and the band’s progress was sabotaged by the arrival of punk. “We looked like a bunch of old men,” Merritt says, “and we were! We didn’t fit anymore.”

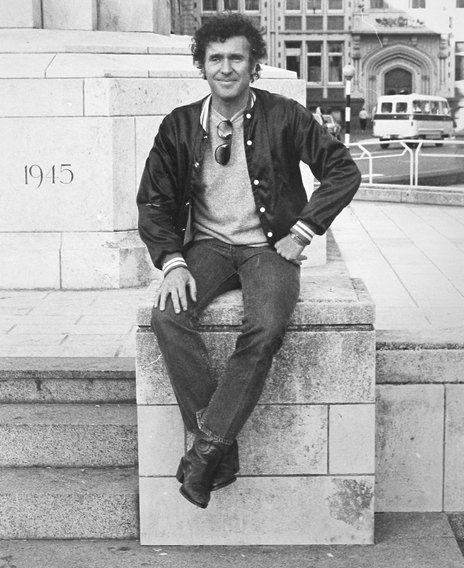

Solo in LA

Disbanding The Meteors, Merritt shifted to Los Angeles in 1978 and two solo albums followed (Keeping In Touch and Black Plastic Max), with Merritt touring Australia every two or three years. In 1990 a reformed Max Merritt and The Meteors played The Gluepot, Max’s first NZ performance since 1966, with a line-up featuring Peter Williams, Bob Bertles, Billy Kristian and Bruno Lawrence.

Subsequent Australian tours were low-key but in 2002 his performances on A Long Way To The Top, featuring a who’s who of past Australian greats, saw Max Merritt’s star rise once again. He became a popular fixture on the summer festival circuit and, touted as Australia’s King of Soul, he was curtain-raiser to some of his musical heroes – James Brown, Ray Charles, and Wilson Pickett.

In April 2007 Max Merritt was inducted into Christchurch’s Rockonz Hall of Fame, preceded by a national tour with Dinah Lee. On his return to LA he was diagnosed with Goodpasture’s Syndrome, a rare auto-immune disease which requires twice-weekly dialysis. “Trust me to get something no one has ever heard of,” Max said. In October 2007, 50 Australian acts – including Daryl Braithwaite, John Paul Young, and James Reyne – rallied together for a concert which raised $AU200,000 for Merritt.

In 2008, Merritt was flown to Australia for his induction into the ARIA Hall of Fame.

Merritt was in a Los Angeles hospital in September 2020 when he died of Goodpasture’s Syndrome. He is survived by his daughter Kelli, son Josh and three grandchildren.

On 22 October 2020 it was announced that Max Merritt was inducted into the The New Zealand Music Hall of Fame.

--

Read more: Max Merritt, the Melbourne years

Read more: Max Merritt, the UK years

Read more: Max Merritt remembered, by John Dix