When Johnny shook, it was down the back of a lower North Island picture theatre and in front of a mirror at home. When he rattled it was around Wanganui province and the surrounding districts, searching for (and finding) an audience. And when he rolled, it was north to Auckland, then across the Tasman Sea to Sydney.

Rock and roll goes to the movies

Devlin’s enduring importance to New Zealand popular culture is as the first great star of the electric era and the technological advances it allowed. Radio, electric guitars, primitive TV, evolving cinema systems and record players – that’s the wave he rode. As talented as he was, Johnny was a willing conduit of greater, inevitable forces. A provincial pop culture fan who absorbed rock and roll and the teenage American and British movies that were shown in nearly every town.

Between 1956 and 1959, rock and roll-related flicks played regularly at local theatres. Some like Rock, Rock, Rock! (1956), Rock, Pretty Baby (1956) and Don’t Knock The Rock (1956), and Hot Rod Girl (1958, cars and rock and roll) fell prey to censor’s shears. The majority – including The Girl Can’t Help It (1956, in full colour), Jailhouse Rock (1957) and Rock All Night (1957) – played unabashed.

New Zealand teenagers may have been galvanised by Bill Haley and The Comets’ 'Rock Around The Clock', as Redmer Yska suggests in All Shook Up: The Flash Bodgie and the Rise of the New Zealand Teenager in the Fifties (1993), but they most likely heard the music first on the soundtrack to the film Blackboard Jungle (1955), released in NZ in September of that year.

Up there on the big screen, New Zealand’s young could see it all. The musicians. The singers. The clothes. The moves. The songs. Even when rockers didn’t make it onscreen they could be heard on the soundtrack. The pull of the music was so strong that local theatres listed the film’s songs in ads.

Scene one

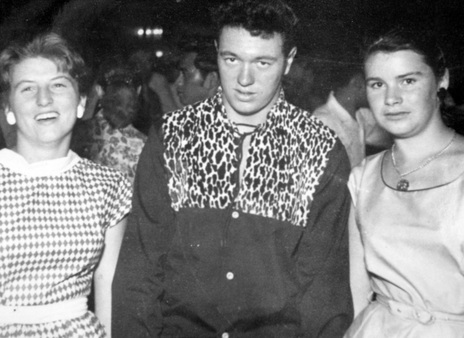

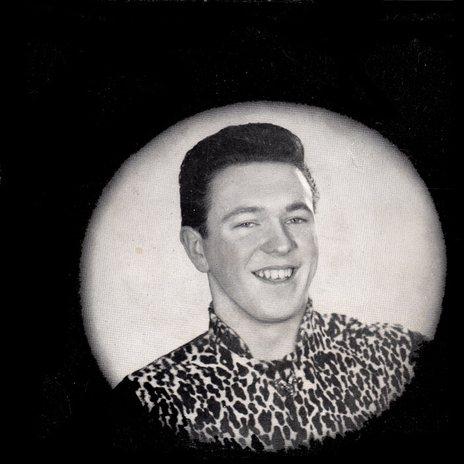

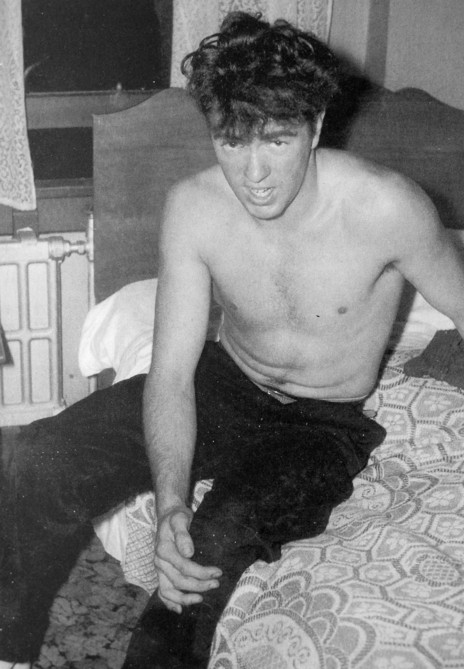

It’s not surprising, then, that Johnny Devlin’s early life played out like a Hollywood B-movie. The plot: A small town boy, who can’t settle, finds life onstage in the mid-1950s as a champion body builder and singer in his brothers’ country and western group, The River City Ramblers. Chopping and changing jobs in Wanganui, he meets Johnny Cooper, a wily (Māori) promoter and sometime rock and roll singer with strong country roots, who has already recorded Haley’s early hits’ ‘Rock Around The Clock’ (in September 1955) and ‘See You Later, Alligator’ in May 1956.

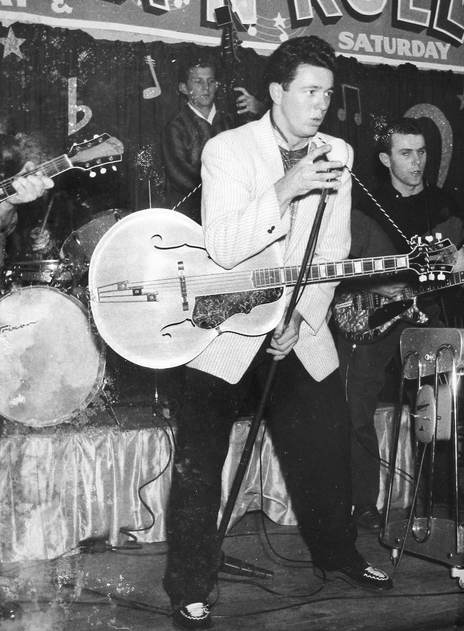

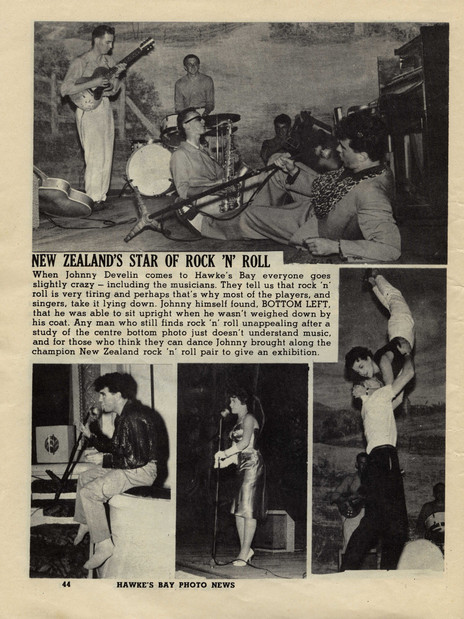

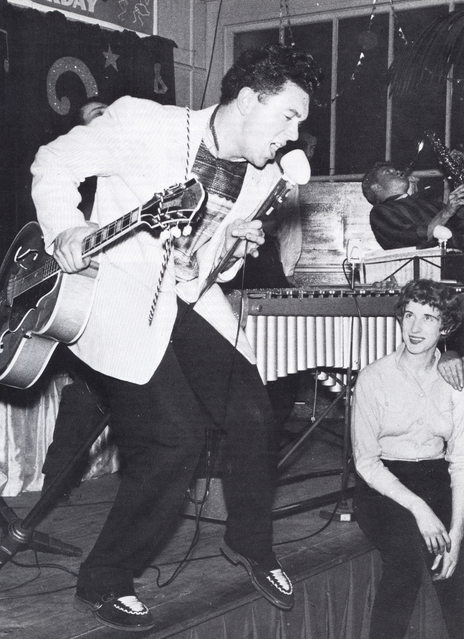

A QUICKLY ARRANGED, ELVIS-INFLUENCED STAGE TURN SEALS THE TEENAGER’S FATE

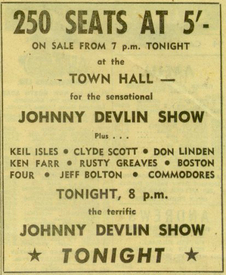

They strike a deal where Devlin kicks back half his winnings from the talent shows that Cooper organises. An early lesson for the leather-jacketed Devlin. More paid work comes a-knocking and the Wanganui rocker takes to uncertain roads on his new motorbike, his guitar strapped across his back. By August 1957, he’s performing in Napier and Palmerston North and topping the bill at the Wellington Town Hall as “New Zealand’s newest and greatest Elvis” at the 11th Festival of Jazz.

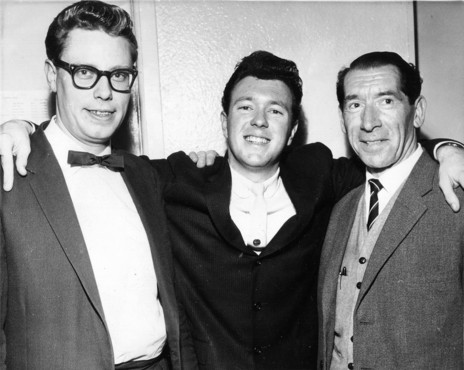

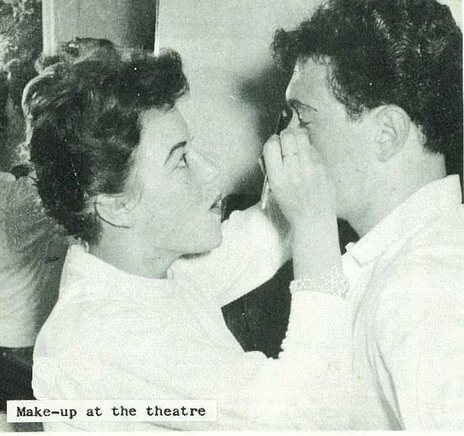

Dunningham takes Devlin in hand, putting him into a Jive Centre residency, finding him work in a warehouse, and helping with his speech and media presence. When Johnny, in a moment of doubt, books a rail ticket home, his new manager leans over and pulls the ticket from his hand, tearing it in two.A relationship break-up in January 1958 pushes Devlin north by train to New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland, where a “chance” encounter with old friends, dancing duo Dennis and Dorothy Tristram, takes him to The Jive Centre run by Dave Dunningham. A quickly arranged, Elvis-influenced stage turn elicits an immediate, ecstatic reaction and seals the teenager’s fate.

Scene two

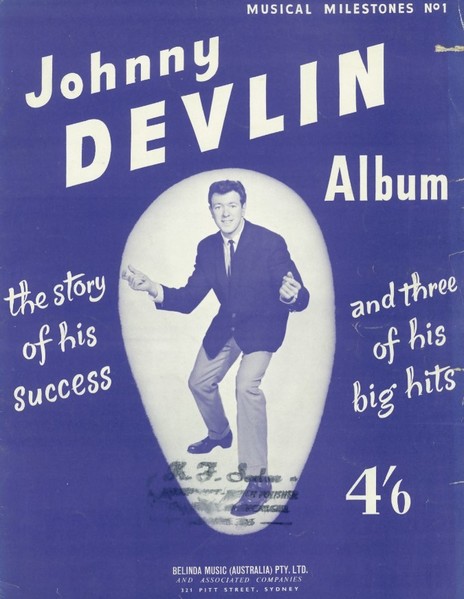

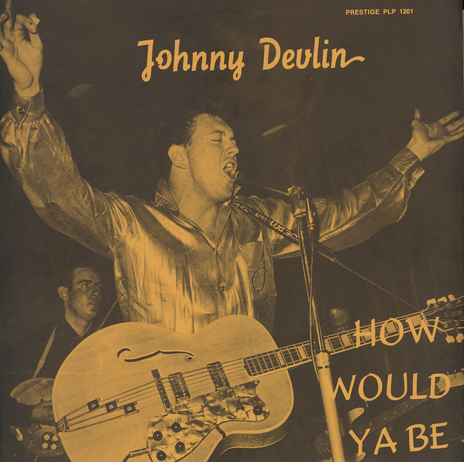

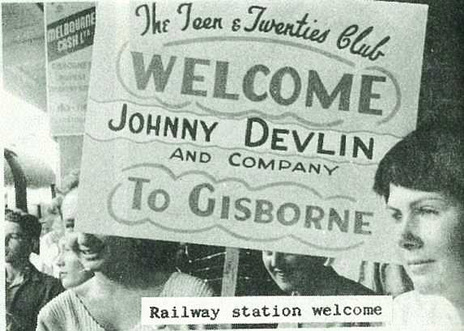

Devlin’s first single, ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’, a Lloyd Price-penned, Elvis Presley-covered song recorded with a pick-up band of Auckland jazzers and Devlin’s brothers singing back-up as The Three Ds, is a hit in June and July 1958 on Phil Warren’s initially reluctant Prestige Records. Enlisting the help of young theatre manager and emerging PR whiz, Graham Dent, a nation-long tour is planned for November 1958, after successful small tours closer to Auckland.

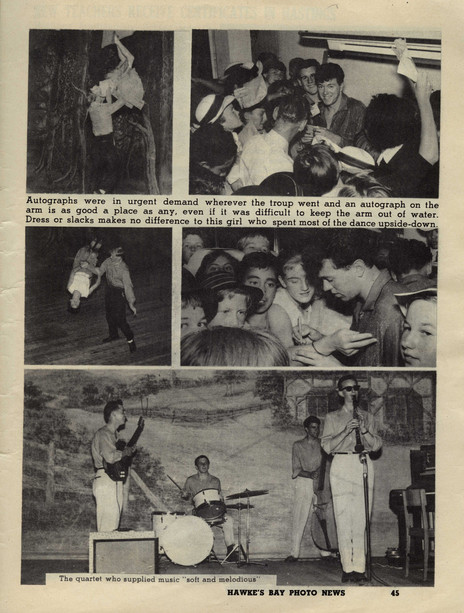

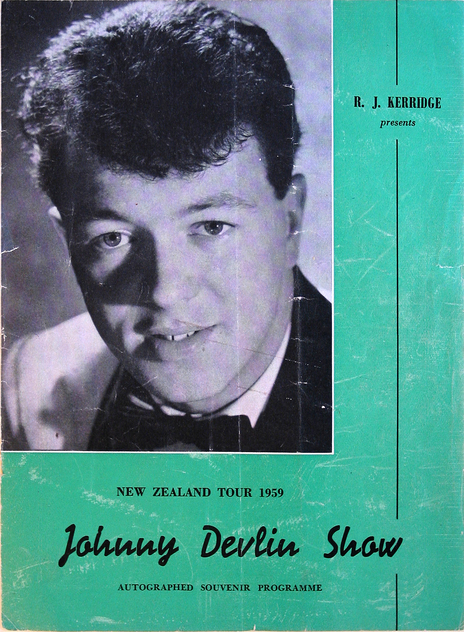

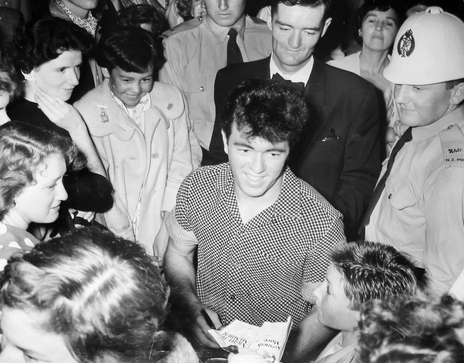

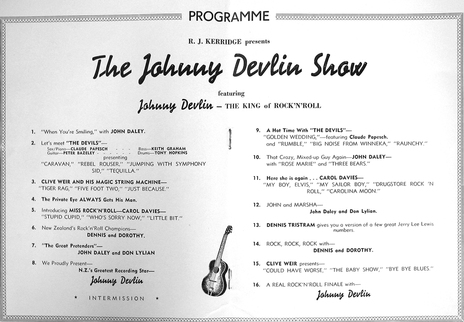

Movie chain mogul R.J. Kerridge takes on Johnny Devlin’s wildly successful, breakout national tour of late 1958, which runs in Kerridge Odeon theatres and halls through into early 1959. It was a perfect synergy; picture theatres were already a rock and roll friendly space. A teenage space (when teenage movies ran). Putting live rock and roll music in them made sense. In centres such as Hamilton, one theatre – the Embassy – was already available to touring acts. Well before Devlin first visited the Waikato city in August 1958, live rock and roll had already been seen and heard there. “The only juvenile rock and roll band in the Waikato", the “apricot and black” clothed The Deadly Cravats had raised the curtain for Rock Baby - Rock It in October 1957. The show proved popular enough to warrant return dates.

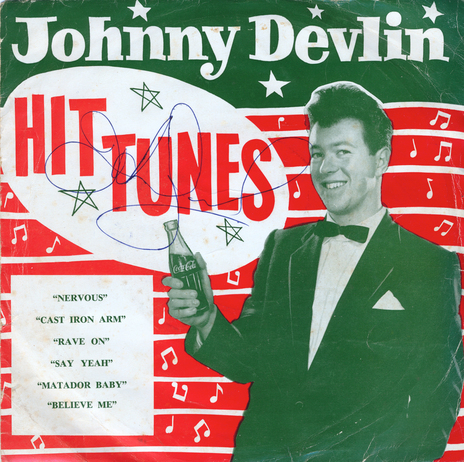

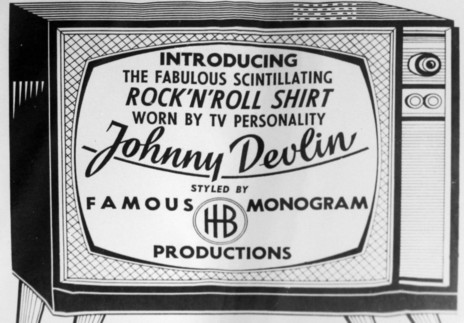

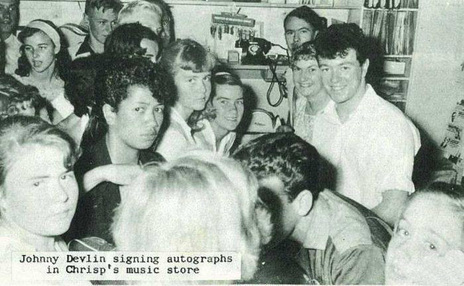

New Zealand wasn’t virgin territory for the new sound. Rock and roll groups existed throughout New Zealand. What Devlin had more than the others was the star quality that came out of a cool back story, a ready grin, fearless dress sense and a firm grip on the new teen vernacular. An appeal fuelled by a taboo-stretching stage act liberally sprinkled with Elvis and Buddy Holly tracks, hip sponsorship from Coca Cola, and by new manager and Prestige Records boss, Phil Warren, along with Dent’s wily PR tricks, which stretched to shirt ripping, fake fainting, big (bogus) cheques, inflated sales figures and celebrity encounters.

Rocking in the milk bars

Hearing rock and roll outside the live or movie setting proved more difficult. The nation’s tightly controlled, family orientated radio network was conservative and censorious, allowing only a few hours a week to popular music, rock and roll included. Milk bars and coffee lounges – already demonised (and glamourised) by the New Zealand Government’s Mazengarb Report (November 1954) into moral delinquency – filled some of the void, with jukeboxes packed with the latest hits, as did record store listening booths.

All of which pushed teenagers out of the family sphere and environment, allowing the entry of new influences. A rearrangement and stretching of cultural space was facilitated by the increased teenage mobility allowed by cars and motorcycles, in turn funded by wages from a buoyant economy. Wages that could just as easily be applied to hire purchase agreements for the new Murphy, Pye and Clipper branded, detached radiograms to play the lithe, newly introduced 45rpm 7-inch singles that dominated record sales from 1957 on. Record sales were booming on the back of rock and roll. A good chunk of which, Devlin was generating himself.

Lawdy Miss Clawdy

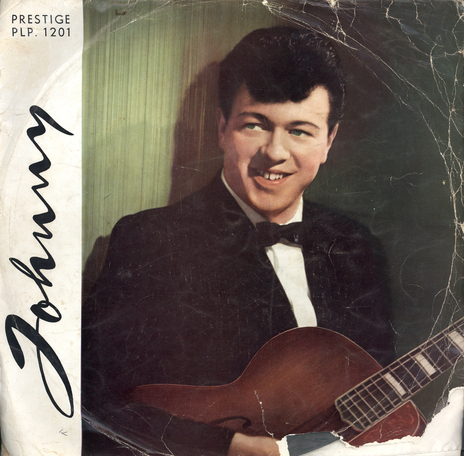

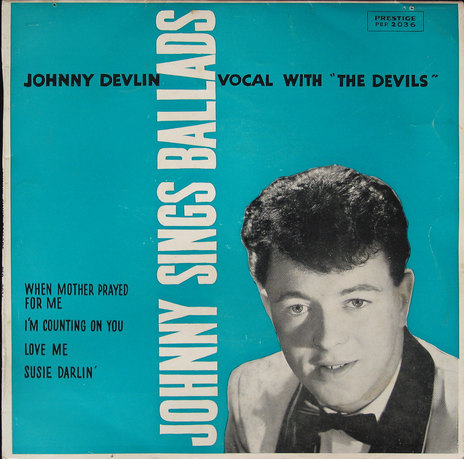

Between June 1958 and mid-1959, Johnny Devlin released 11 big selling hit rock and roll singles and an album, Johnny, in New Zealand. Drawing on Phil Warren’s access to regional hits and non-hits from the United States – which came down the culture chute from America with the jazz that Prestige Records was also releasing – Devlin quickly carved out a strong catalogue of his own.

His first recording session, capturing ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’/‘When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again’ with a group assembled by Bernie Allen at the Jive Centre in April 1958, was promising. His second session with The Bob Paris Combo in Auckland in June and July 1958 is more revealing and better realised.

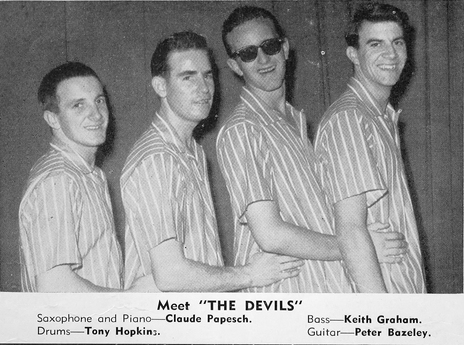

Devlin entered the studio in early 1959 with The Devils – a group blooded on his national tour.

When Devlin recorded, he didn’t draw from the pool of black and white gospel, R&B and country swing songs that Presley did, he took his songs instead from contemporary recordings, which were using an amalgam of those sounds. ‘I Got A Rocket In My Pocket’, his first defining hit, and its flipside, ‘You’re Gone Baby’ were copped straight from Jimmy Lloyd, a Kentucky-born singer who shared Devlin’s C&W roots (as others did). Its title alone, with a sly wink to teenage sexuality and space age mobility, said it all, although Devlin brought plenty of grit to the sound as well.

That set the pattern for covers of songs by Texan rockers Gene Summers (‘Straight Skirt’, ‘Nervous’, ‘Gotta Lotta That’) and Terry Noland (‘Patty Baby’); North Carolina’s Wayne Handy (‘Say Yeah’), Jimmy Carroll from Michigan (‘Big Green Car’), West Virginia’s Johnny “Peanuts” Wilson (‘Cast Iron Arm’) and Chuck Howard from Ohio’s ‘Crazy Crazy Baby’. Rockabilly rebels, all, frantically working a hit sound in its peak period – 1956 to 1959.

When Devlin entered the studio for the third time, in early 1959, he was backed by The Devils – Claude Papesch (piano/saxophone), Keith Graham (bass), Peter Bazley (lead guitar), and Tony Hopkins (drums) – a rock and roll friendly group blooded on Devlin’s national tour.

Australia

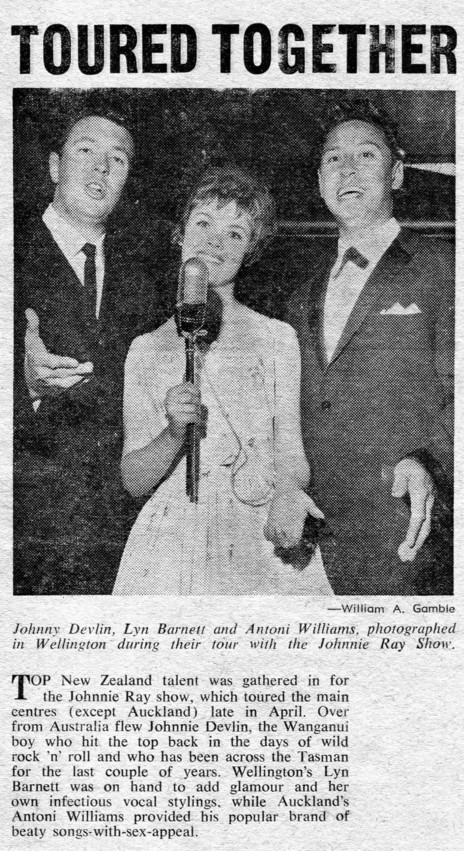

With his live popularity assured and a headline-making profile established, Devlin’s New Zealand rock and roll march ended in May 1959. The 21 year old headed to Sydney where Phil Warren had booked him onto The Everly Brothers’ Australasian tour. It was the second time a prominent rock and roll associated act had toured New Zealand. Gene Vincent and Johnny Cash were the first in April 1959, on a tour steered by Warren.

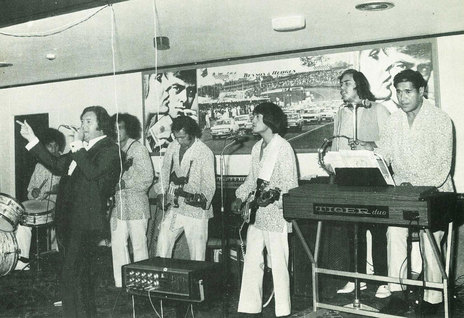

Devlin wasted no time getting established in Australia, where another emerging medium presented itself. Television. New Zealand’s best quickly became a regular on pop music shows, including Six O’Clock Rock, Bandstand and Teen Time. Then there was Rock n’ Roll, a 1959 documentary filmed around the Rock'n'Roll Spectacular, a rock concert at Sydney Stadium that featured Devlin and the best of the Australian response.

In July, Johnny Devlin and The Devils took Australia’s side at the Lee Gordon-promoted The Battle of the Big Beat, which pitted Oz rockers against Americans Lloyd Price and Conway Twitty, among others, in concert. Johnny had now not only appeared on film, he’d shared the same stage as the man who wrote his first hit.

His own hits weren’t long in coming. A cover of George Jones’s ‘White Lightning’ was backed with a Devlin original, ‘Doreen’, which appeared on promoter Lee Gordon’s Leedon Records in Australia.

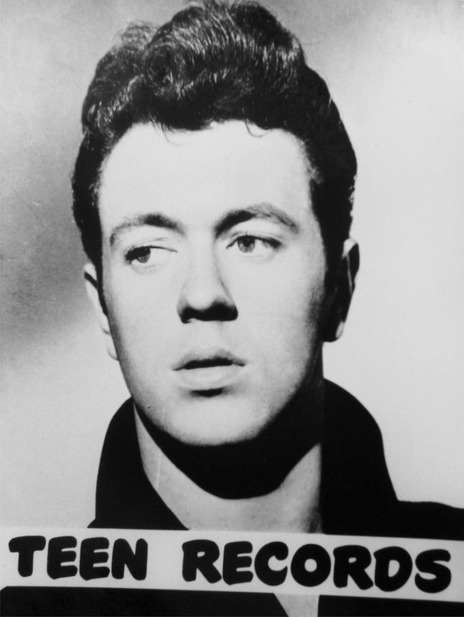

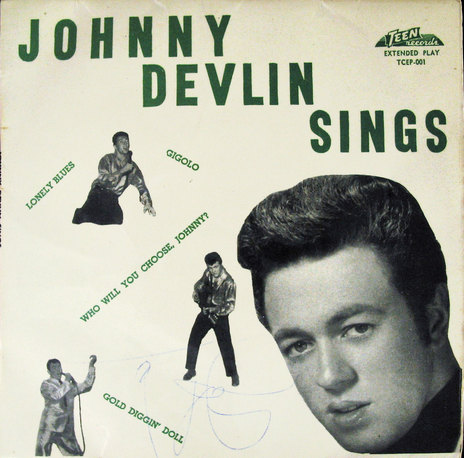

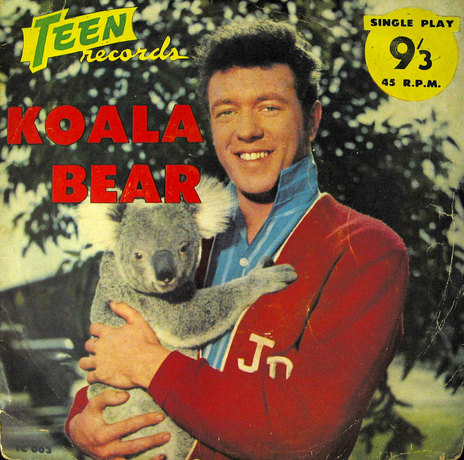

Devlin had already been writing his own material in New Zealand, having seen the real power and money lay there and in production. A short stint on Columbia Records produced two singles (his final releases in NZ on Prestige Records) backed by vocal group The Delltones, before Devlin signed to John Collins’ Teen Records and the floodgates opened. A mix of solo releases, including ‘I Gotta Be True’/‘Big Hunk O’ Love’, and group releases with The Devils followed.

Devlin and Collins’ ‘Koala Bear’ hit No.3 on the Sydney charts, No.27 in Melbourne and No.2 in Adelaide. ‘Gigolo’ backed with Devlin’s ‘Baby, I Miss You’ also charted Top 30 in those markets in 1959. The following year, he scored big again with novelty track, ‘Got A Zack In The Back of Me Pocket’ (with The Bricks and The Deneers), which climbed to No.7 in Sydney, No.17 in Brisbane and No.8 in Adelaide. Devlin’s ease at overcoming traditionally parochial Australian audiences was credited to his being billed as an “international” artist.

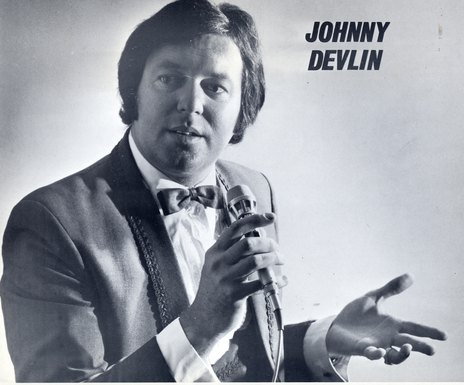

The Johnny Devlin that showbiz reporter John Berry encountered on a visit to Auckland in October 1960, was a changed man: “A smart businessman in a single-breaster suit, with well trimmed haircut and his teeth capped, Hollywood style. He was still the cheerful Johnny, but now he was a mature entertainer,” Berry noted. Which was the way music was going. The ever-aware Devlin, who was also writing a music column for Pix magazine, rode the rapidly changing chart tastes of the time with professional ease, carving out records for himself and his backing group, The Devils, in imitation of Cliff Richard and The Shadows. He also grabbed visiting stars Hal Blaine (drums) and Scotty Wilkinson (guitar) to back him on ‘I’m Gonna Love You’ and ‘Wicked, Wicked Women’ (Teen Records, 1960).

Devlin also wrote songs for Australian pop artists including The De Kroo Brothers and Patty Ann Noble, who scored a big multi-state hit with ‘Good Looking Boy’ on HMV Records in 1961, which, with her two other Devlin-penned discs was released in England.

Johnny’s own light continued to shine on a series of singles for Festival Records, which included ‘Stayin’ Up Late’, a Sydney and Brisbane hit in 1962 that was also available in the USA on Coral Records in 1963. By then, he had his own publishing company, Devlin Music, and had taken on the production and management of Sydney surf instrumental group The Denvermen.

My Little Rocker Turned Surfie

Devlin arranged for The Denvermen’s debut single to be released on HMV Records, but it tanked. Devlin’s next attempt, the instrumental ‘Surfside’, pushed the early wipeout from memory, climbing to No.1 on the Sydney charts in January 1963. Melbourne liked it too, awarding it No.6. The other states soon followed. More hits came for The Denvermen as Johnny did what he’d done with The Devils, splitting off the backing group for their own successful releases and putting them behind Digger Revel for yet more hits, including Johnny’s ‘My Little Rocker's Turned Surfie’, a No.9 hit in Sydney in January 1964.

His backing singers on that track were the young Bee Gees.

The Denvermen also backed the Devils-free Devlin on his own surf hit, ‘Stomp The Tumbarumba’, a no.5 hit in Sydney and Melbourne for Festival Records. His backing singers on that track were the young Bee Gees, who also joined him in 1964 for takes on ‘Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On’ and ‘Blue Suede Shoes’.

By then, Devlin the writer and producer had left HMV Records to be the A&R manager and house producer at the newly launched RCA Records Australia branch. There he continued to mine the new pop sounds for hits, matching them with singers Tony Brady, Barry Stanton and a visiting Eartha Kitt, along with rising groups such as The Tolmen, The Renegades and The Cicadas, much as he’d done at HMV for solo singers Noble, Kevin Grealy, and Bryan Davies.

The Mod’s Nod

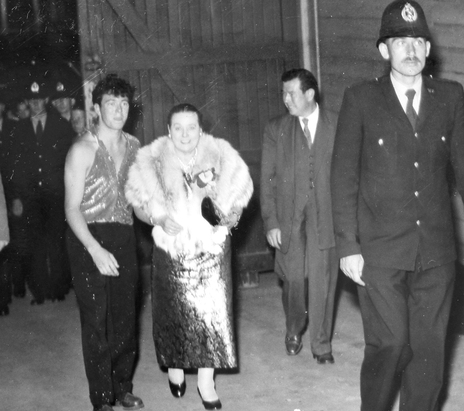

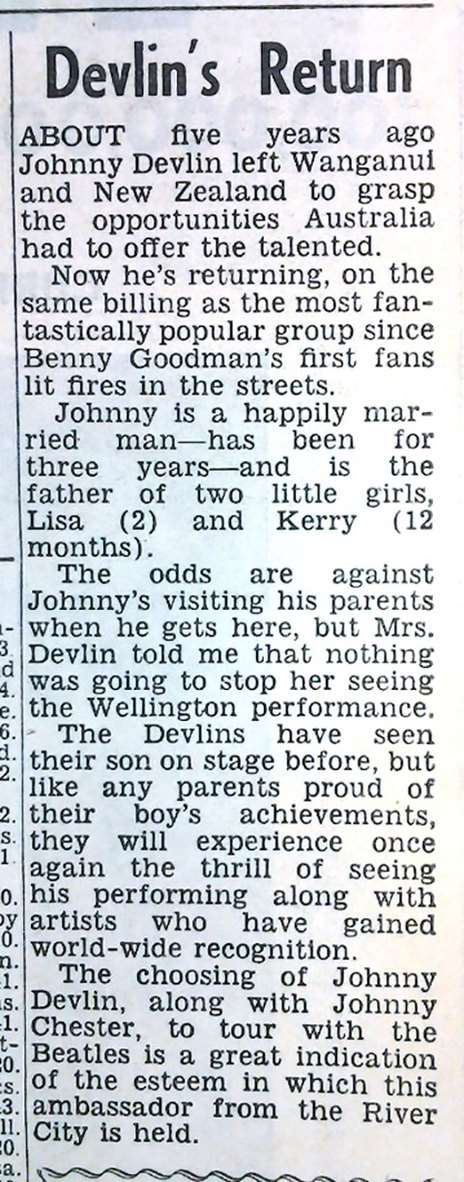

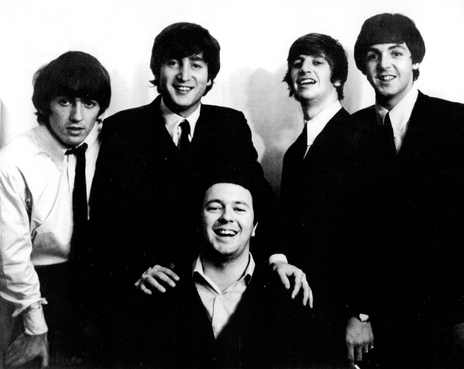

Which seems to have got Johnny excited about groups again. He’d already linked up with The Rajahs (who toured NZ in 1964 and 1965) for ‘The Mod’s Nod’, then formed a new Devils out of Wellington rock and rollers The Tornadoes. He also managed to get himself on the bill of The Beatles’ wildly successful Australasian tour of mid-1964. Film survives of his June, 17, 1964 performance at Melbourne’s Festival Hall, showing a satin-suited Devlin, belting out rock and roll standards and squeezing the occasional scream out of the young audience.

Devlin the performer went into ascent again, adopting a mod image and knocking out yet more (unsuccessful) singles, but there was very little left for Devlin to do in Australia. He’d already conquered the live scene, television and the charts in a country that was one of the strongest rock and roll and surf music outposts in the world.

London then home

Johnny left for England in September 1965 where he struggled to find the success he’d left behind. Live work was fitful, but included gigs at the Empire Ballroom in London, and a singles deal with Columbia Records that produced some promising orchestrated big ballads, including 1966’s ‘Hung On You’, a Righteous Brothers B-side, and the country-ish ‘Tender Loving Care’.

He was back in Australia by June 1967, working TV and the lucrative club scene, and producing groups such as Lloyd’s World, a late 1960s Sydney group with a phased, psychedelic-pop sound not dissimilar to The Fourmyula. And that’s where he’d stay, outside several years spent in New Zealand in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Back home, Devlin performed regularly live and on TV and released the Bernie Allen-produced ‘The Games Are On’ (about the Christchurch Commonwealth Games) in 1972, while peppering the willing local press with stories of planned casinos in South Auckland, the appointment of Peter Posa to Johnny Devlin Enterprises as musical director and associate producer for the company's recording label Kontact, and an ice skating accident. Actual records were harder to find.

Devlin continued to ride the rock and roll currents on records and package tours whenever that perennial sound came back into favour, such as Johnny O’Keefe-inspired The Good Old Days of Rock and Roll in 1974 and 2006’s New Zealand The Best of The Best. Country music also had a revisit in the early 1980s.

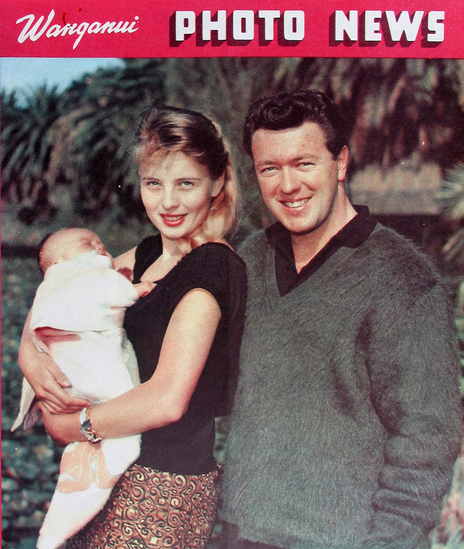

New Zealand, which has seen its first son of rock and roll regularly over the years, awarded Johnny Devlin the Recording Industry Association of New Zealand’s first “Legacy Award” at the New Zealand Music Awards in October 2007. That same month, Ode Records issued a compilation of Johnny’s rock and roll sides for Prestige. In January 2008, Johnny added the New Zealand Order of Merit to his list of achievements, followed two months later by an induction into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame. The veteran rocker has released over 60 singles, 18 EPs and eight albums in his long career.

--

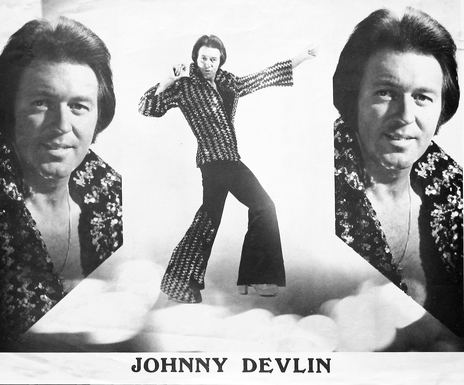

Rock & Roll Encounter: Johnny Devlin