Karaitiana was a pivotal member of the two pioneering rock and roll bands that emerged from Christchurch: Max Merritt and The Meteors, and Ray Columbus and The Invaders. In the late 60s he was a member of the house band on the TV pop show C’mon – then he really began to display his chops.

He joined Headband, Tommy Adderley’s jazz-rock fusion group; in the mid-70s he moved to Britain, where he was part of many leading groups that also featured expatriate New Zealanders: Ian Carr’s Nucleus with Brian Smith and Roger Sellers; Pacific Eardrum with Dave MacRae and Joy Yates; and Night with Chris Thompson (and Rolling Stones’ pianist Nicky Hopkins). Since returning to New Zealand in 1983 he has produced many albums, and he continues to play gigs and the occasional recording session.

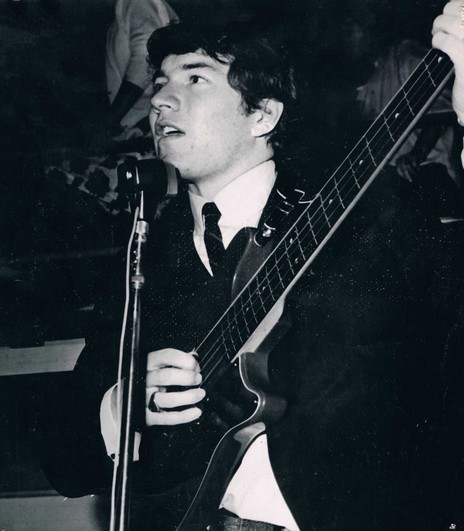

at the age of seven, KARAITIANA WAS ON THE ROAD playing bass FOR THREE WEEKS.

Born Wiremu Karaitiana, his early years were spent in North Brighton, Christchurch, and his family moved to the suburb of Linwood just as he started school. His father Kahu – a distant cousin of ‘Blue Smoke’ writer Ruru Karaitiana – was a band leader and tenor who performed with Inia Te Wiata in the 1964 all-Māori production of Porgy and Bess. This toured New Zealand and Australia at the same time as the Invaders were topping the charts with ‘She’s a Mod’.

Kahu Karaitiana’s band played Hawaiian-style swing while his mother Violet – a Cockney – danced the hula. Billy began playing the ukulele with them, and was invited by prominent local guitar teacher Tommy Kahi to go out on tour. A bass player was also needed, so Billy was thrown in the deep end. “Tommy taught me a couple of positions and then said, ‘Now you know everything! If you get lost, go to the top string, nobody else knows' – and that’s been the philosophy all way along.”

Karaitiana was just seven years old, and on the road for three weeks. “It was ridiculous, really,” he told me in 2001. “But it was a positive start.” The tour lasted three weeks, playing South Island venues. His introduction to rock and roll came early in his teens, when his father took him to see Martin Winiata’s band at the Union Rowing Club in Christchurch. Famous for his ability to play two saxophones at once, this much-loved big band leader had shifted with the times, ditching swing for rock and roll with his band the Moonmen.

Karaitiana went to Linwood High School with Max Merritt, but it was Ray Columbus who approached him to play bass in a band called the Saints. “I was oiling the chain on my bike, and Ray introduced himself and said, ‘I’ve come to have a listen to you.’ Ray says I auditioned him – he always remembers me saying, ‘Can you sing?’.” Columbus’s Saints only did one gig, supporting the Trinidadian boogie-woogie pianist Winifred Atwell. Another short-lived band followed: Saki and the Jive Five. “That was good, the first rock and roll band that was swinging – but it didn’t last long.”

Then Max Merritt called. His band was already well-known at places such as the Hibernian dancehall in Christchurch. “That was a rough gig, with the bodgies all in one corner with all the widgies. In another corner were the seamen from Lyttelton, and all the Māori were in another corner. You picked which corner you wanted to be in. There were lots of fights.” When fighting broke out the band played ‘Rumble’ as a signal for the bouncers to sort it out. The Hibernian was rough, but good fun, with real rock and roll dancing. Wearing petticoats and frilly skirts the girls were flipped over the backs of their dancing partners. “It used to be a cool thing for a guy to be a jiver. A lot of young Māori dancers did that then. It was exciting to watch.”

Karaitiana made his first recordings with Max Merritt and the Meteors at the 3YA radio studio in Christchurch. The band also toured the South Island, with several stints playing Joe Brown’s Saturday night dance in the Dunedin Town Hall. “I remember Joe Brown unplugging us once because it was too loud. You used to get a lot of that in those days.”

As an apprentice mechanic, Karaitiana made £2/12/0 a week – about $5 – whereas he was paid £10-12 pounds playing at a dance. After four years’ apprenticeship, the offer of a Friday-night gig in Dunedin brought things to a head with his boss: Karaitiana needed to take time off. “He said, you’ve either got to be a musician or a mechanic. Our gig in Dunedin was worth £40. So when you’re earning £2 for a 40-hour week as a motor mechanic, what do you do? You go to Dunedin. It was probably the best thing that happened to me, because then Max said, ‘Let’s go to Auckland’.”

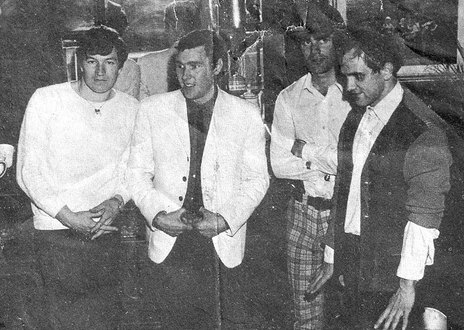

In 1962, the Meteors were the top band in the South Island, followed closely by the Invaders. With Merritt at the wheel of his XK150 Jaguar, they drove north. The Meteors secured a residency at the Top Twenty on Durham Lane, found a good following for their lunchtime and evening gigs, and also continued to tour out of town. They even ventured briefly over to Australia, playing a TV show called Hootenany Hoot featuring Sheb Woolley of ‘Purple People Eater’ fame.

Then Karaitiana bailed out on the Meteors. Why? “Max and I had a bit of a tiff,” he recalled. Another band member was also disgruntled, so the pair made plans to form their own group. “He said to me, ‘You hand your notice in first’ – and then he never handed his in. It was a rort to get me out of the band to get his mate in. He took over my position.”

Karaitiana spent about three months performing in clubs in Noumea before he got a call from his old friend, Ray Columbus: there was a spot in the Invaders, who were about to try their luck in Australia. “This happened because Puni [Solomon] jumped off stage when some guy was dancing with his girlfriend. Puni bopped him. And Ray, being Ray, said ‘You’re fired’. I got the call the next day.”

He arrived back in New Zealand just before the Invaders flew to Sydney. The clubs of King’s Cross in 1964 were eye-opening and exciting. The working girls – and the transvestites at Les Girls – were pretty, and there were many bands playing. “The young Bee Gees used to watch us play in a club, they were already quite well known.”

In Sydney, there was fierce rivalry between the Invaders, the Meteors and Billy Thorpe’s Aztecs.

In Sydney, there was fierce rivalry between the Invaders, the Meteors and Billy Thorpe’s Aztecs. “But Ray and I were tight. Max Merritt’s band had more soul, while Ray’s was more of a pop band – but a great band.” Promoting ‘She’s a Mod’, they had to play the industry game, aka payola. They would take DJs out to lunch, buy them drinks, and hope they’d play the single. “Or you’d shout the whole bar a drink. That’s how to get records played on air.”

After nine months, Ray Columbus and the Invaders reached No.1 in Australia with ‘She’s a Mod’, and it stayed in the charts for over a year. “It was a great breakthrough for New Zealand music. And we were a strong band; Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs were strong, but mainly because of volume.”

Thorpe’s manager, John Harrigan, also managed Surf City, so the Invaders often played with the Aztecs, as well as package tours with people such as Del Shannon and Peter and Gordon. Despite being national chart-toppers, they were treated poorly, so while on a plane touring with the Aztecs the Invaders demanded better conditions from Harrigan. “He dumped us off in Adelaide and left us stranded. Then Harry Miller saved us.”

Miller, the flamboyant Auckland promoter, had recently shifted his business to Sydney. He offered to pay the Invaders’ fares back to New Zealand. When they got home, the band immediately received a legal demand from Miller. “He sued us straight away for the fares,” said Karaitiana. “It was a bit strange. Harry wanted to manage us. But we made him our agent.”

The Invaders returned to Australia in 1965 to be on the same bill as the Rolling Stones and Roy Orbison. (By this stage Billy Karaitiana was known as Billy Kristian.) At a rehearsal before the tour, the Invaders had first dibs on some new equipment that Orbison had brought from the USA. “It was like Christmas time for us. Then in walked the Stones and all the crew. Mick does his thing – he dances while we’re playing, it makes us feel corny. Keith comes in and says, I want that and that … everything. It was a bummer. So we had to go and get Twin amps. Bill Wyman said you can use my amp – a Vox Foundation, which I used. He was the only one to loan us gear. Meanwhile Wally [Scott, the Invaders’ guitarist] and Keith Richards were having a few problems.” The pair had a contretemps backstage, which ended with Scott holding a smashed Jansen guitar.

On opening night, just as the Invaders were about to go on stage, Harrigan arrived and put an injunction on the band, and told Miller they were still under contract to him. “It was true – any bookings had to be through John Harrigan. But Ray was smart and so was Harry. There was a big meeting. Harry leaned over to Ray and said, ‘Make me your agent.’ Ray says, ‘You can have these boys, but it’s going to cost you $10,000 a night.’” Harrigan was aghast: “I can’t afford this!” “Ray said, ‘Then your option’s gone’ – and we were on stage in half an hour.”

The Invaders formed a special bond with Roy Orbison, who they backed on the tour. “He was always into the black jokes, there was a lot of camaraderie on that tour by the time we’d finished it.” Towards the end, Orbison asked Kristian and Scott to join him on a tour in the States, but visa problems prevented this from happening.

The Invaders themselves were stymied; they were based in New Zealand and could draw big crowds in Australia. There was also, suggests John Dix, the feeling that perhaps they had peaked in these markets. The next step, Columbus reasoned, was to shift the band to the USA. However visas were again denied. “In many ways, not going to the States finished the band,” says Kristian. He and drummer Jimmy Hill left to join Max Merritt’s Meteors, and Columbus – with an American wife – went to the US alone.

AFTER billy Kristian SUPPorted the rolling stones with the meteors, Bill Wyman gave him his unique Vox Teardrop guitar.

With the Meteors, Kristian got to tour with the Stones again – and afterwards Bill Wyman gave him his unique Vox Teardrop guitar. Kristian had been lobbying to buy it, and at the end of the tour the Stones roadie/pianist Ian Stewart took him to Wyman. He opened up a case and inside were two bright red Teardrops. One was Wyman’s prototype, with F-holes; the other was a solid body. Wyman picked up the solid body version and said, “It’s yours.” Kristian still has the instrument, though it was once stolen, requiring him to buy it back.

This second stint with Merritt didn’t last long, “because I’m a non-drinker. Bruno Lawrence was in the band then, and after a while, Max and Bruno were drinking a lot.” Kristian had already handed in his notice, and the band was on a cruise ship in the Pacific, heading for Auckland, when he got into an argument with Lawrence about drinking. “There were fisticuffs – me and Bruno scuffling round the bed, both of us in tears not wanting to hit one another. When we got to Auckland, Bruno jumped ship. He’d had enough.” Kristian stayed on the boat to Sydney, and then left the band to join the Keil Isles.

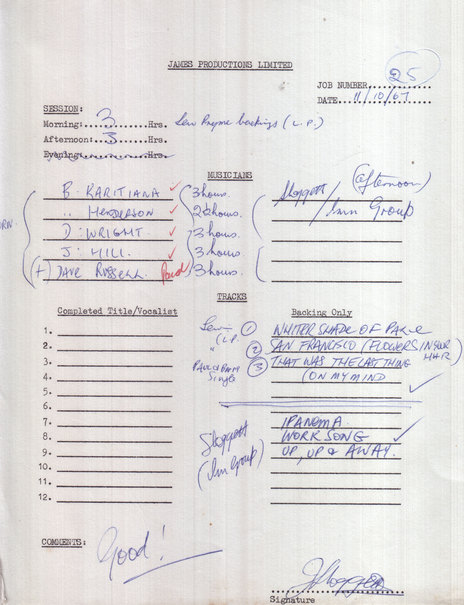

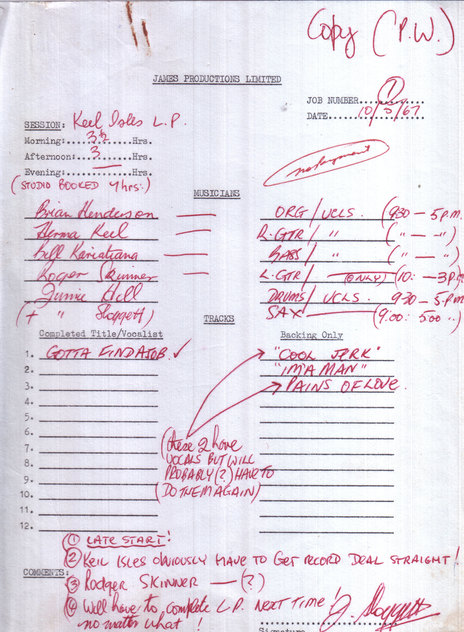

The Keil Isles had been recruited to be the house band for the NZBC’s Saturday evening pop show C’mon, which was essential viewing in the late 1960s. The show had its stars – the Chicks, Shane, Mr Lee Grant, Sandy Edmonds – but the band was always featured prominently, even taking the spotlight as vocalists. A recording of Kristian singing ‘Cool Jerk’ is one of the few clips from the legendary series that still exists. “The band was just as important as the artists on the show,” says Kristian, who credits this idea – and the success of C’mon – to producer/director Kevan Moore. “He was a very advanced thinker, with modern ideas – he’d just come back from London.”

The show was rehearsed on Saturday mornings, then pre-recorded at 6pm. It went to air at 8pm, with the musicians watching themselves in the green room. “Kevan had a thing about quickness – everything was fast moving, and Peter [Sinclair] use to talk flat out. He’d talk so fast, and he’d never forget a line. Kevan was a good producer, he’d walk round with his pipe, and have a go at people in his way.”

While the show was off air, for three months the cast travelled the country in a C’mon package tour. In hotels, the stars got their own rooms, while the bands had to squeeze in together. The troublemakers on the tour were The Underdogs, who decided they would see how long they could go without washing. “It was unbelievable. When you got those boys on the show, there was havoc.”

In 1969, Kristian was working in the Logan Park cabaret band led by Jimmie Sloggett when he got a call from Wally Scott in Hong Kong. It was an invitation to join Renaissance, an ace band led by Peter Nelson (formerly of the Castaways), which had a residency at the Hilton hotel. “We were the highest paid band in Hong Kong, and spending a lot of money.” For two years, Kristian played in the Hilton and toured through the East with Renaissance.

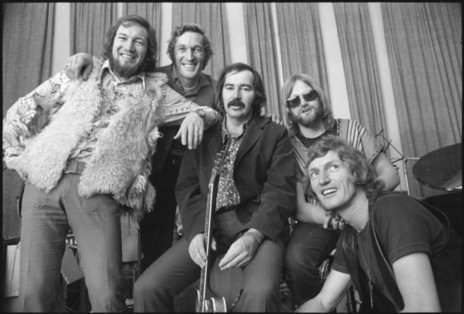

On his return to New Zealand in September 1971, he and Jimmy Hill joined Headband. A group of seasoned players, Headband fused jazz, rock and electric blues, with Tommy Adderley as vocalist and Dick Hopp on electric violin and flute. With this line-up, Headband immediately recorded an album at HMV studio in Wellington, inviting an audience in and performing the music like a live show. “The album was called Happen Out because we had a bugbear about the TV show – it was too cabaret. So we went the other way.” The album included three hit singles: ‘The Ballad of Jacques Le Mere’, ‘Good Morning Mr Rock N’ Roll’ and ‘Love is Bigger than the Whole Wide World’.

Headband would “play the Tainui Tavern till 10 o’clock, then head into town and play till three in the morning at Granny’s.”

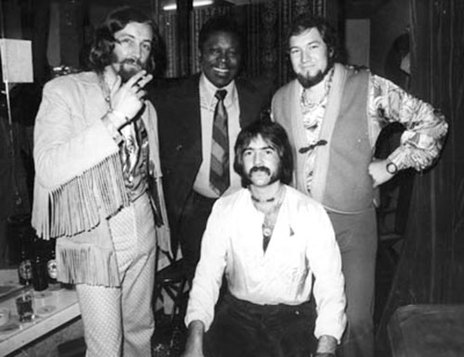

Headband held court at Granny’s, Adderley’s own club on the site of the old Top Twenty club. It was open to the public, but punters had to become members to try and get around the strict liquor laws. Police kept visiting and taking away the alcohol, wanting to make test case of the law. But the club became famous for other transgressions. “They were very drug-ridden days, and a lot of the music reflected that,” recalled Kristian. It was also legendary for hosting visiting overseas musicians after they had performed in Auckland, such as the Rolling Stones and John Mayall.

Out of Headband emerged another band of top-shelf New Zealand players: Kristian, Walker, Hamlet and Hill. His cohorts were pianist Mike Walker, singer Chris (Hamlet) Thompson, and Jimmy Hill. The band was serious about its music, but didn’t take itself too seriously. “We’d play anything and everything.” They would play extended jams on songs such as ‘Papa Was a Rolling Stone’: “That was far-out stuff in those days. This was 1973 – we’ve got beards and long hair, we dressed unruly. We’d play the Tainui Tavern till 10 o’clock, then head into town and play till three in the morning at Granny’s. We got to know each other’s playing, and we’d just branch off. Mike would play different chords while Chris was still singing, and we’re thinking, ‘Where is Mike going now?’ And we’d just follow it – it becomes like a Pink Floyd trip.”

The scene was changing: with 10 o’clock closing, pubs were refurbished with stages and employed bands to mostly play covers. Thompson and Walker left for the UK, while Kristian played sessions and spent a short stint running a nightclub (“I wasn’t cut out for that”). Then he, too, headed overseas. First stop was Australia, where for a year he played with Billy Thorpe in a band called Million Dollar Bill, before flying to London.

He arrived with no money and a good camera; selling the camera to Bruce Lynch enabled him to buy a bass and start working. “It was winter, and damp, but I hung out there for a year. Then I started to get work through my friends Dave MacRae and Joy Yates.” The duo formed Pacific Eardrum, a group dominated by New Zealand expats such as MacRae, Yates, Kristian and saxophonist Brian Smith. Kristian played on their self-titled debut, in 1977, and its sequel Beyond Panic the following year.

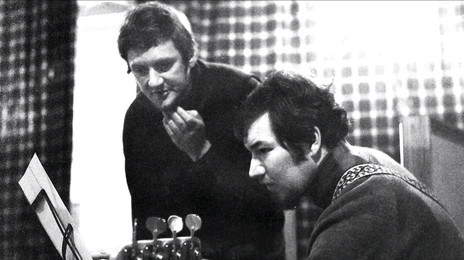

At the suggestion of drummer Roger Sellers, Kristian auditioned for Nucleus, a jazz fusion band led by respected trumpeter Ian Carr. Perhaps it was being Scottish that led Carr to employ many expat musicians from the South Pacific, including Brian Smith and Bruce Lynch. Kristian was hired after the audition, then after a day’s rehearsal the band got in a Volkswagen and drove to Germany to record a live concert the following day. To make things more difficult, Carr had a fondness for writing pieces in very complicated time signatures. “Just weird, and difficult,” said Kristian. “I’d never played anything like this before. It was the terror of my life.”

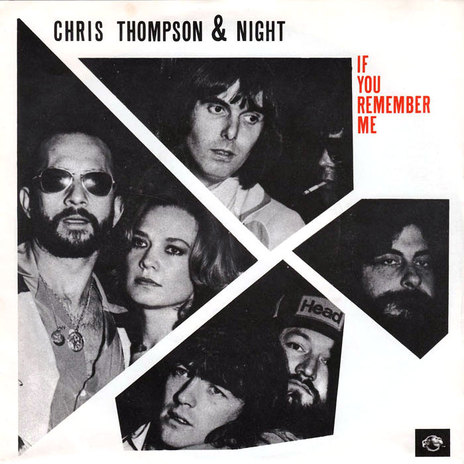

There was no shortage of gigs, with the finest musicians in London. Kristian also played three nights a week in a “low-down dirty blues band” at the Bridge, a pub in Canning Town. In Filthy McNasty the ambition was just to have fun, but the players were big names and old friends: Mike Walker and Chris Thompson (who was simultaneously in Manfred Mann’s Earth Band), as well as session singer Stevie Lange and guitarist Geoff Whitehorn. Filthy McNasty evolved into Night, an all-star outfit. This band was offered a deal, and soon found itself in Los Angeles at Paramount studio – without Walker – to record with slick pop producer Richard Perry (Carly Simon, Nilsson, Ringo).

“We had a good contract, better than the Eagles had. But they were better songwriters, that wasn’t our strong point. It was an itch in our side.” Perry re-shaped the band, sacking the drummer and pianist. Night became an all-star outfit at another level, with Nicky Hopkins – pianist for the Stones, the Kinks and the Beatles – and drummer Rick Marotta (Steely Dan, Asia). Perry also gave Night a West Coast groove, which “killed the band,” says Kristian. “We weren’t like that, we were a dirty blues band, and ended up clean cut. We were looser people, not high-class session musicians.”

Nevertheless, ‘Hot Summer Nights’ was a hit, reaching No.18 in the USA, and No.1 in Australia; it was later featured on the Top Gun soundtrack. The band went on tour for three months supporting the Doobie Brothers, though standard practice at that level is for the support act to pay to play. Nevertheless, the tour was worthwhile – playing to 20,000 people each night, meeting people such as Michael Jackson and Bill Payne. He got to play with Jim Keltner at a party when the bass player didn’t turn up, “So I jumped in. You meet people in the oddest of circumstances.”

Although ‘Hot Summer Nights’ received airplay worldwide, the album Night didn’t sell what was hoped. But there was a follow-up album, Long Distance, and Kristian was satisfied with the whole experience. He went back to London, and the phone kept ringing for a bass player. He even worked on a session at Abbey Road, produced by Paul McCartney.

But London had changed in just a couple of years. Punk bands had taken over the pub gigs, with the result that there were fewer venues – for all bands, let alone “muso” bands. He missed his children, who he had left behind in New Zealand when his marriage broke up. In early 1983 he returned to Auckland, where he managed Mascot Studios for Hugh Lynn and produced sessions.

Karaitiana came back to New Zealand buzzing, full of ideas, of new things he wanted to do.

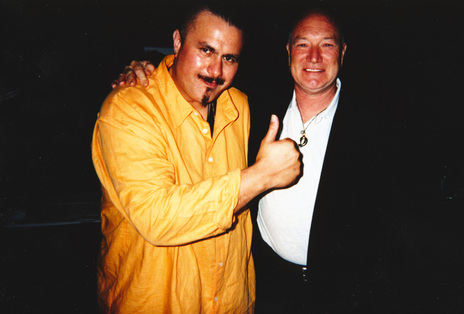

“I was buzzing, because even though New Zealand was behind, it’s only an attitude. I came back full of these ideas, of new things I wanted to do.” Herbs had a new momentum with the recruitment of Charlie Tumahai, back from years overseas with Be Bop Deluxe, and Kristian produced their hit albums Long Ago and Sensitive to a Smile.

Kristian had always felt at home in the studio so – feeling restless after three years working at Mascot – he set up his own studio at home in Kingsland. He called it Muscle Music, and his first session in 1993 was producing Herbs performing the Invaders’ hit ‘Till We Kissed’, with a cameo appearance from Ray Columbus. It was the beginning of a cultural coming home for Kristian.

In the late 1990s Kristian and his wife Trish Mateparae moved to the far north, basing Muscle Music at a settlement called Mangonui. In his own studio he continues to produce music, including three Tui Award-winning Māori pop albums (for Cecily Pohio, Ruia Aperahama and Whirimako Black), plus the soundtracks for many documentaries. And the phone continues to ring for a bass player, be it his neighbour and C’mon collaborator Ray Woolf, his moonlighting sax friend Brian Smith, stars like Georgie Fame, or promising unknowns.