Merv Thomas

No other musician could claim to have backed the young rock’n’roller Johnny Devlin, and built the tape machine on which they originally recorded his debut single ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ in 1958, to have played Dixieland jazz at Mt Eden’s Crystal Palace ballroom during its heyday in the late 1950s into the 60s, to have played the four-note trombone hook crucial to Allison Durbin's biggest hit – and also to have appeared on the Verlaines’ Flying Nun album Bird-Dog in the late 80s.

Merv Thomas at Auckland Town Hall, 2002.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas - 1932 Jazz Orchestra, Auckland, 1998.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

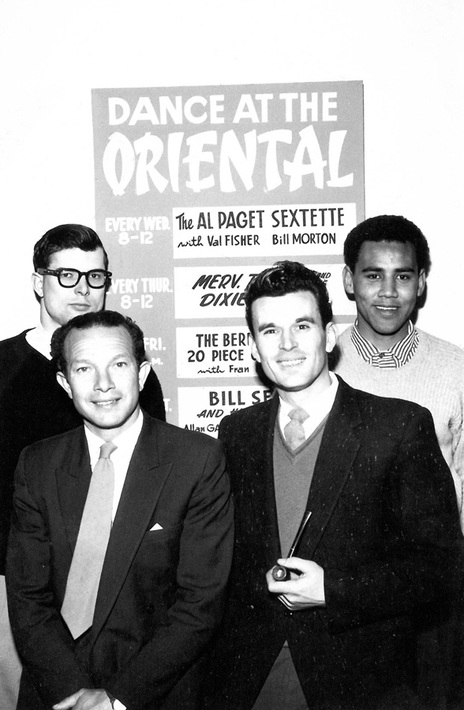

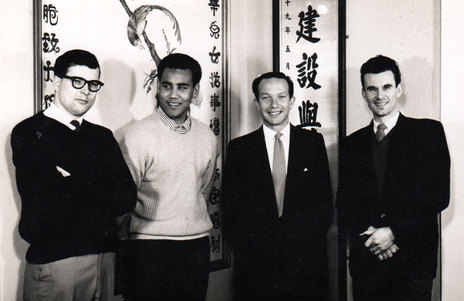

Four Auckland bandleaders ready for their residencies at the Oriental Ballroom, Symonds Street, July 1962. From left: Bernie Allen, Bill Sevesi, Merv Thomas and Al Patchett

Photo credit:

Phil Warren Collection

Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962 (L-R): Bernie Allen, Brian Spence, Morrin Cooper, Stewart Parsons, and Merv Thomas. Obscured is bass player Bernie Hanssen.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas at the Pumphouse, Takapuna.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

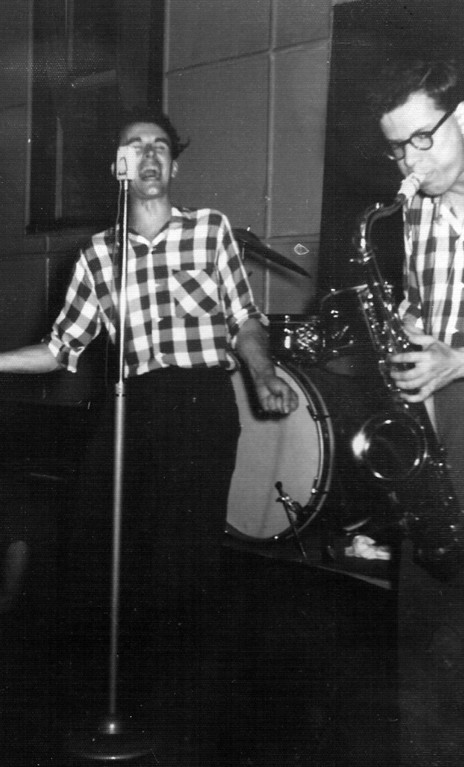

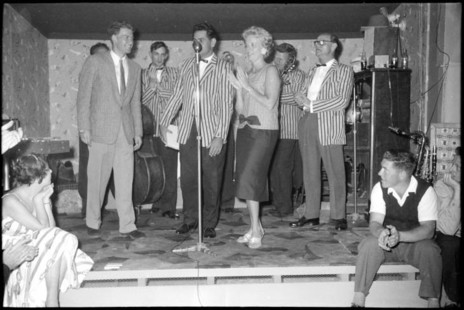

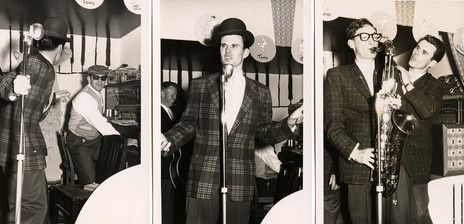

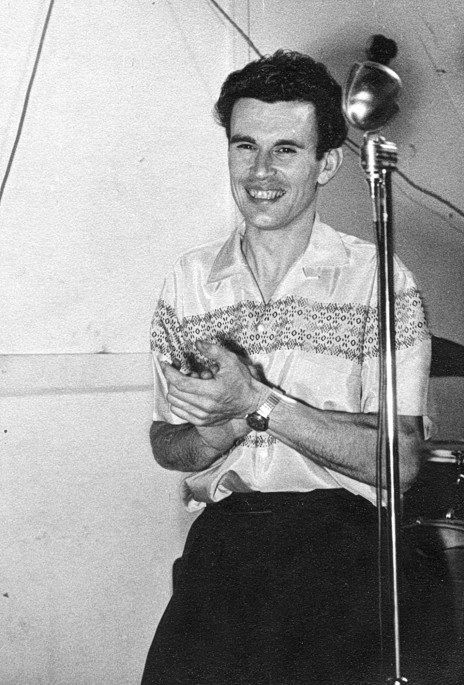

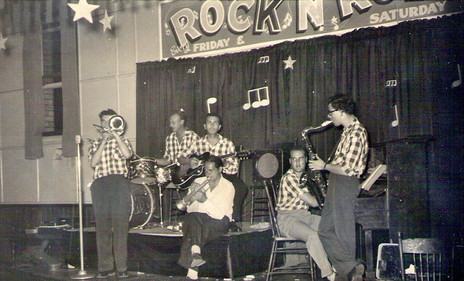

Merv Thomas at the microphone, Jive Centre, 1957; Bernie Allen on sax.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, 1932 Jazz Orchestra

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas with drummer Tony Hopkins.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, ham radio enthuisiast, 1990s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

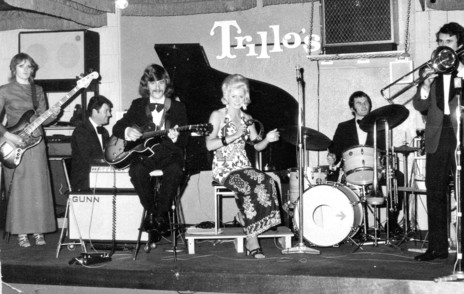

Cliff Trillo's Westhaven Group.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas on TV with Max Cryer and the Children, mid 1960s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

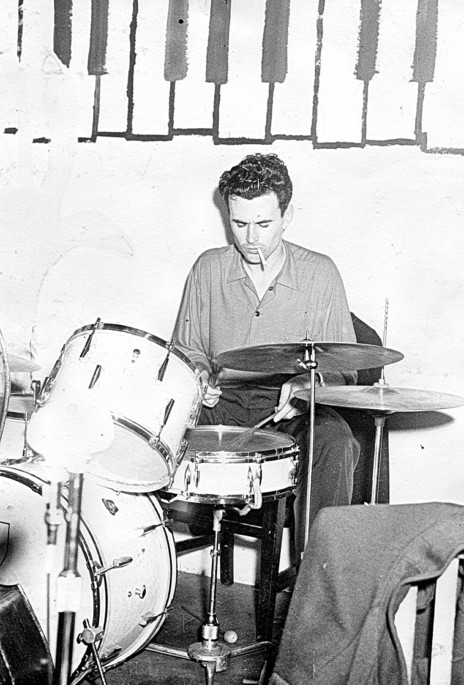

Merv Thomas on the drums, early 1960s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders, Crystal Palace Ballroom, early 1960s. In the front line are, from left: Clive Laurent, Merv Thomas, Tony Ashby.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

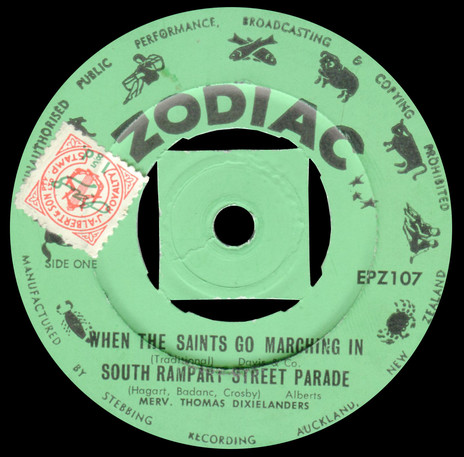

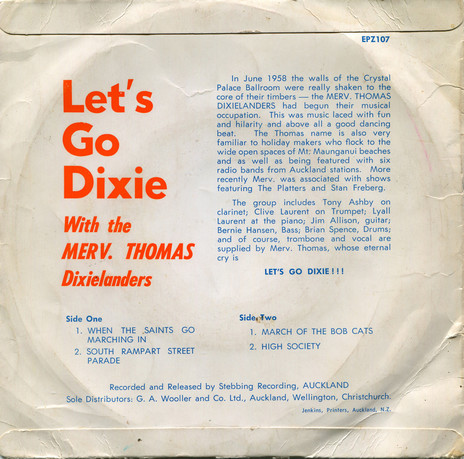

Merv Thomas and his Dixielanders - When the Saints Go Marching In, South Rampart Street Parade (Zodiac, 1959). A reviewer at the time wrote, "The zany dance hall vocals by leader Merv Thomas are missing but none of the spirit of dixie is lost. In fact, here is a serious but spirited rendering of four dixie classics."

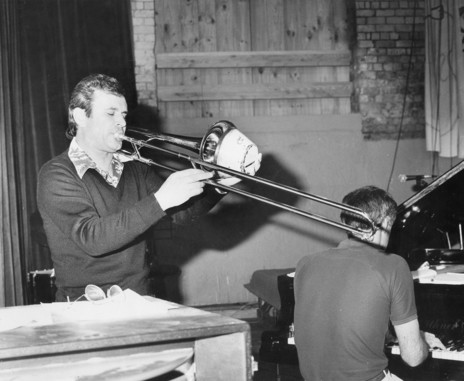

Merv Thomas, Neophonic, Windsor Castle, Auckland, 1973.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

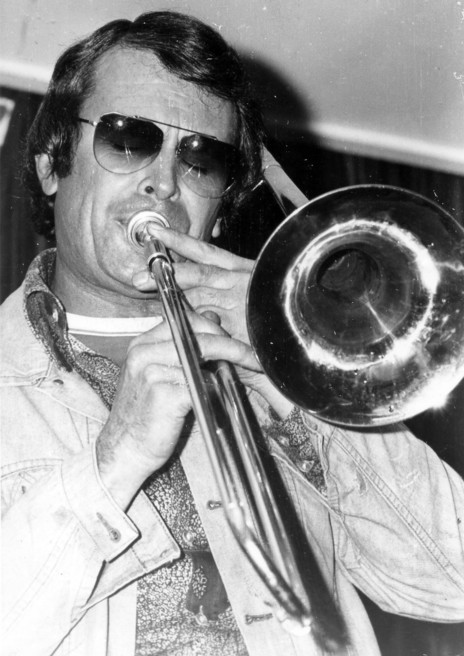

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

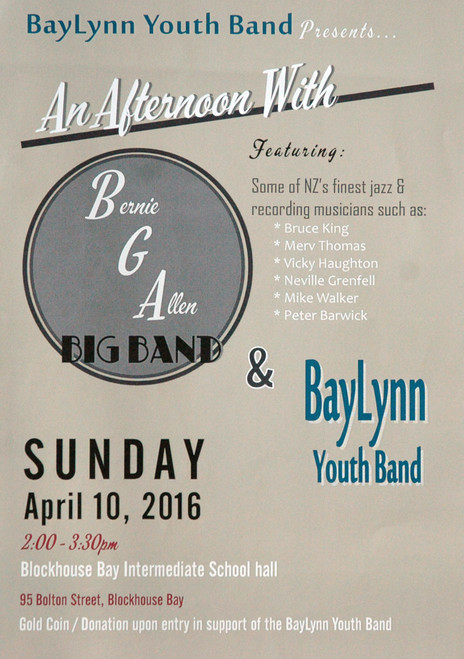

Bay Lynn Youth Band poster.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

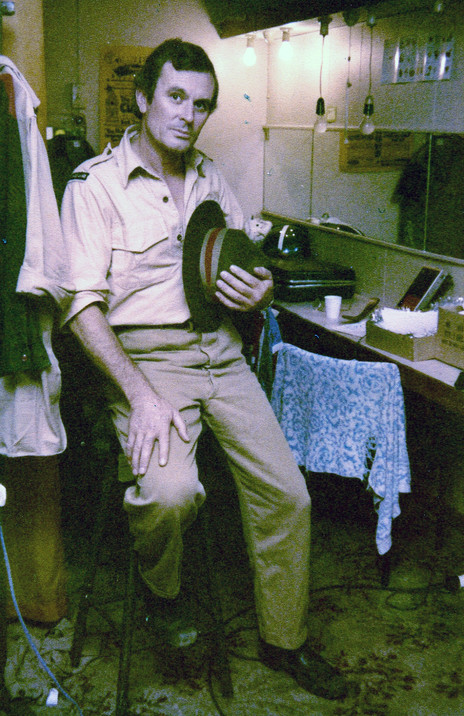

Merv Thomas in the Eliza Keil band, Fiji 1970.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

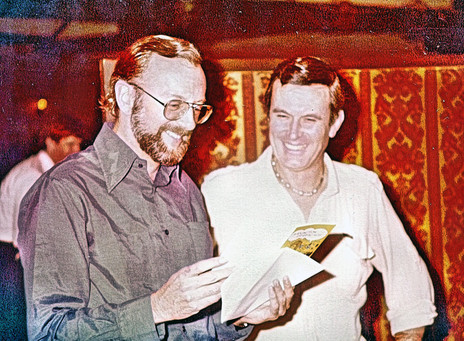

Merv Thomas (back to camera), Johnny Devlin, and guitarist Jim Allison.

Photo credit:

Auckland Libraries, Rykenberg Collection, 1269-K160-27

Merv Thomas and the Bridge City Jazz Men, Birdcage Tavern, Auckland.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Bridge City Jazz Men, Mt Maunganui.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Chris Booth, Kim Paterson, and Merv Thomas playing valve trombones in the Birkenhead Library, 2016.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas, left, at a Cotton Club gig, Auckland, late 1970s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, c. 1982.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, Neophonic Orchestra, Windsor Castle, Parnell, 1974.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

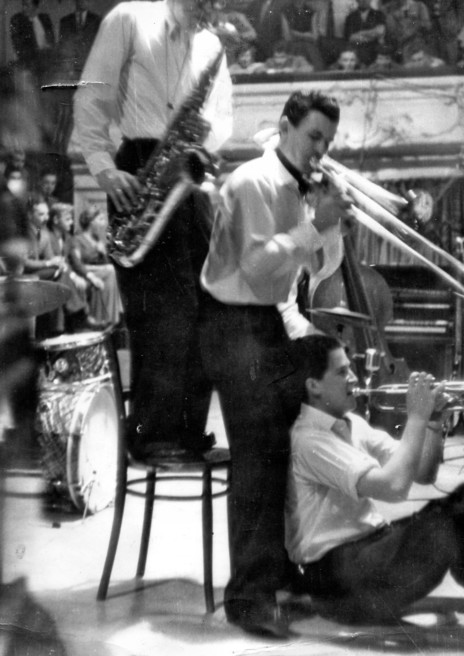

Merv Thomas - Auckland Town Hall, rock 'n' roll, c. 1957.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

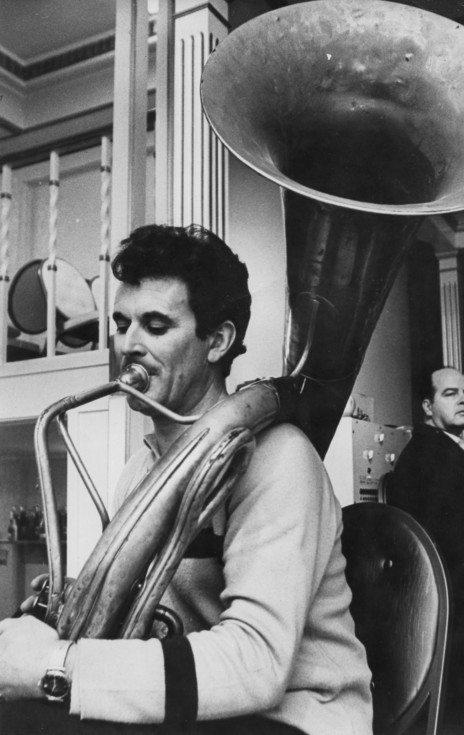

Merv Thomas on helicon - a member of the euphonium family. In the bowler hat is Morrin Cooper.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders at the Crystal Palace Ballroom, 1959

Photo credit:

Rykenberg - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-K0199-11

Merv Thomas at Manurewa Cossie Club.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

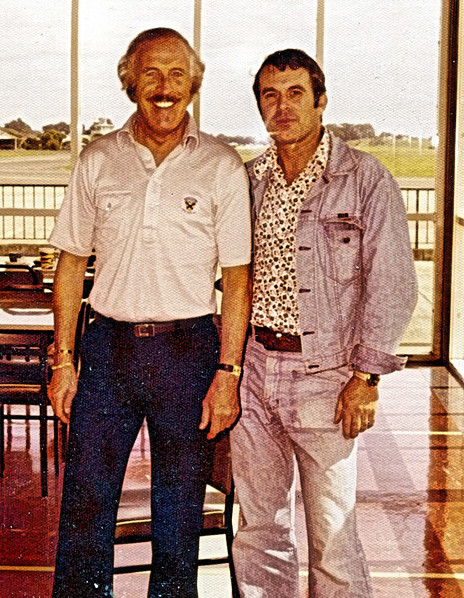

Hadyn Godfrey (right) with Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas at the Jive Centre, 1957

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962 (L-R): Bernie Allen, Stewart Parsons, Morrin Cooper, Marlene Tong, Merv Thomas, and bass player Bernie Hanssen.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

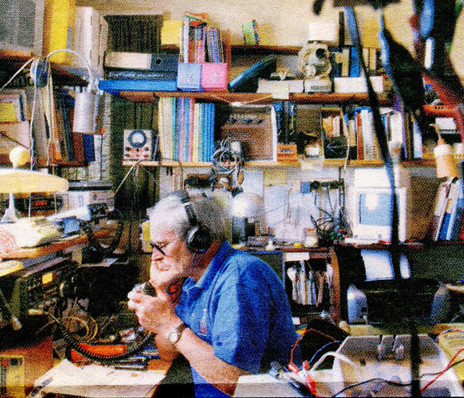

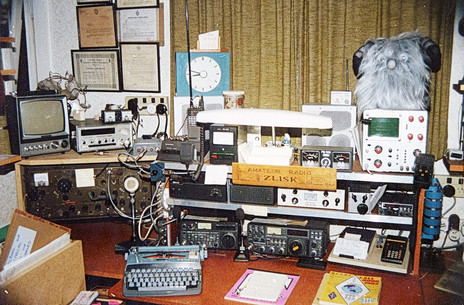

Merv Thomas's ham radio equipment, c. 1980s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, with his lifetime achievement award from the Auckland Jazz & Blues Club, 2020.

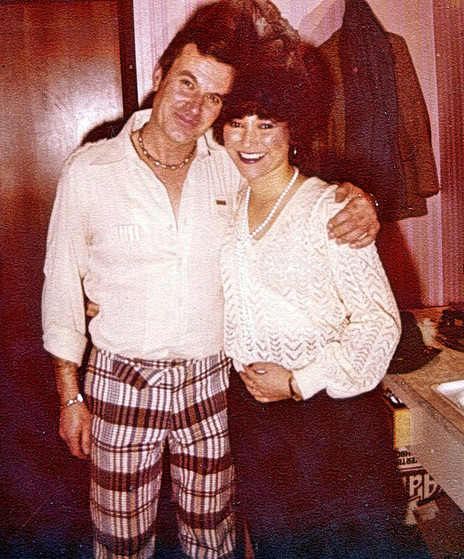

Merv Thomas with Tina Cross, late 1970s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas (trombone) and the Bridge City Jazz Men, 1998. Bruce King on the snare drum.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Dixieland Festival 1992

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Bridge City Jazz Men with Acker Bilk.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

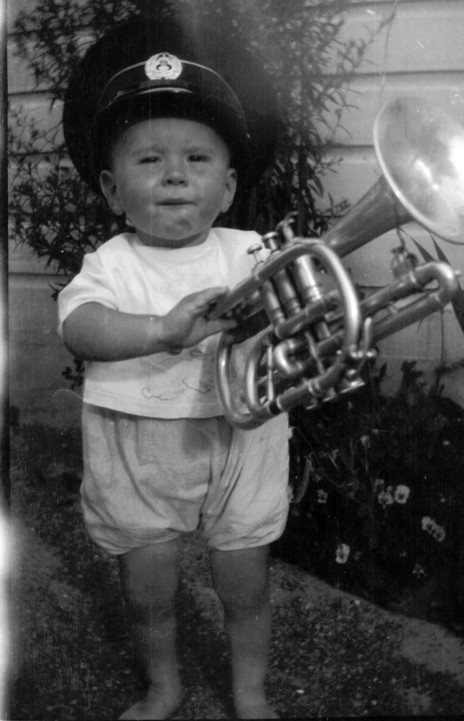

Baby Merv Thomas with cornet and brass band hat.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

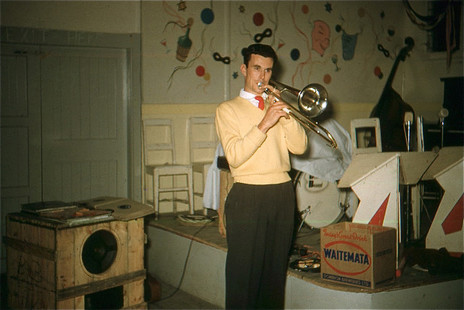

Merv Thomas on trombone at St Seps, Newton, Auckland, 1956.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

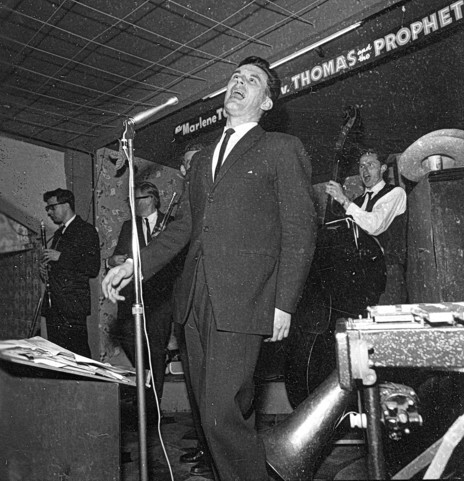

Merv Thomas singing at the Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas with the Kumeu brass band.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas doing their Keely Smith/Louis Prima act, Crystal Palace Ballroom, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

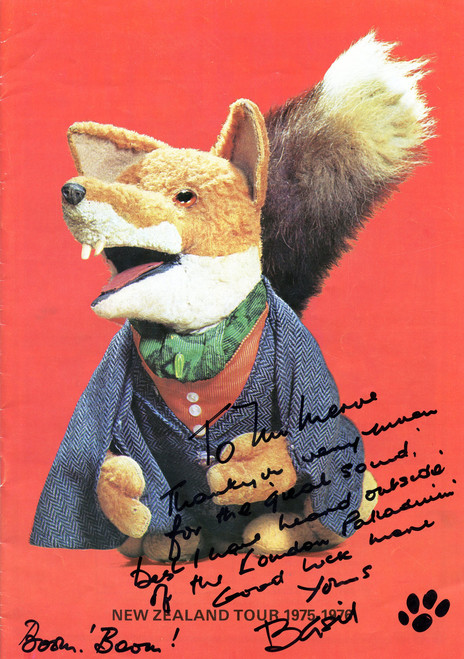

Basil Brush says thank you to Merv Thomas after the 1975-76 New Zealand tour.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Kenny Ball.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

The Merv Thomas Dixielanders - Let's Go Dixie

Merv Thomas at the Downtown Club, Wellington; at left is songwriter and reeds-man Ken Avery.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

It's trad, dad: Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders, Crystal Palace Ballroom, early 1960s. At the piano, Clive Laurent; on saxophone, Tony Ashby

Photo credit:

Rykenberg/Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas having a blow; on the far right is pianist Crombie Murdoch.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas with Peter Barwick, Gables Tavern, Auckland, 28 July 2004.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas (trombone) and the Bridge City Jazz Men, 1998. In front: Bruce King.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Bennie Gunn's ham radio station, 57A Symonds St, late 1950s.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas

Merv Thomas in the "K-Mart quartet".

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

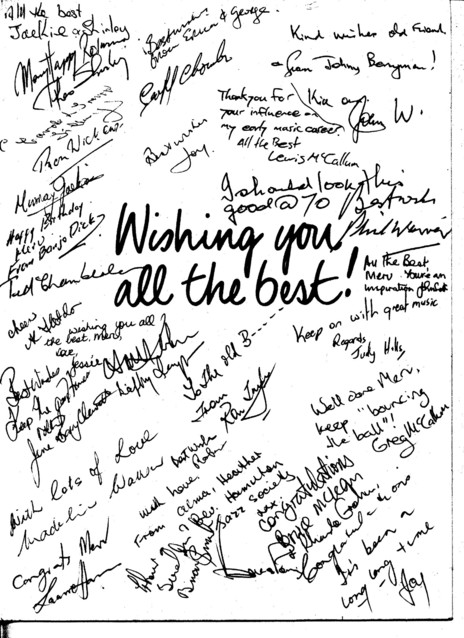

Tributes to Merv Thomas on his 70th birthday.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas, far right, in the Eliza Keil band. Beside him is trombonist Dale Alderton; Crombie Murdoch is seated, alongside trumpeter Murray Tanner.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas reunited with several of the Dixielanders (Tony Ashby on clarinet) – Hamilton 1st Dixieland Festival, 1992.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas (right) and Alan Fletcher.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas. Wally Scott, Manhattan, Mt Roskill, May 1982.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders at the Crystal Palace Ballroom. 1959

Photo credit:

Rykenberg -Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-K0199-02

Merv Thomas and Bernie Allen, many years after their collaboration at the Jive Centre - Birkenhead Library, 2016.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas with UK entertainer Bruce Forsyth (left), 1972.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas working with Bruce Forsyth, 1972.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

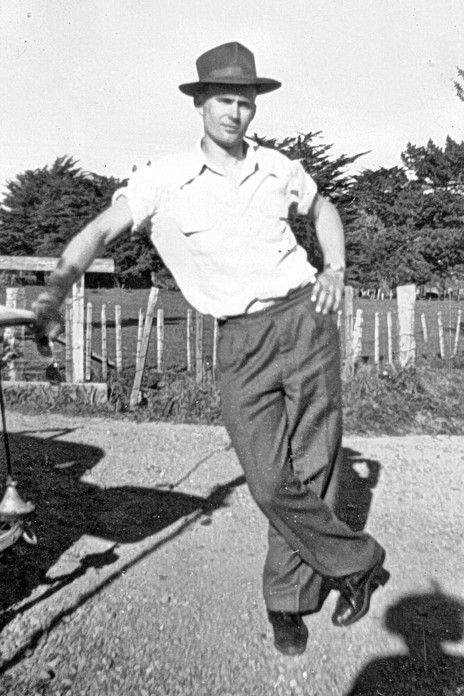

Merv Thomas, warming up for a gig at Mt Maunganui, c. 1955.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas in the Bernie Allen Big Band, Birkenhead Library, 2016

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas, far right, in the Eliza Keil Band, Fiji, 1970. Murray Tanner is second from left.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets; at left are Stewart Parsons and Morrin Cooper. Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and Jimmie Sloggett at the Montmartre, Auckland. Thomas played on many sessions arranged by Sloggett.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, Auckland, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

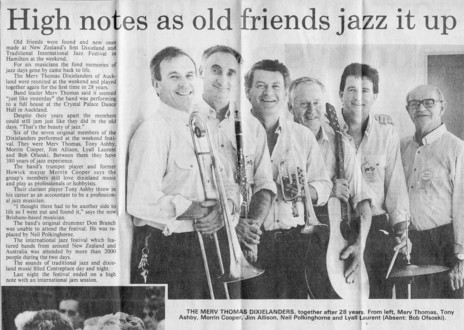

"High notes as old friends jazz it up" – The Dixielanders reunite for the 1st Hamilton Dixieland Festival, 1992.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas on trombone at the Jive Centre; on trumpet at left is Dave Forman.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas with the Eureka Jazz Gentlemen.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas.

Merv Thomas Octet, Peter Pan Cabaret, 1968.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

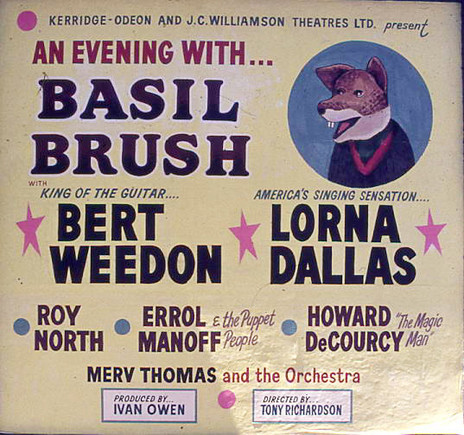

Poster for An Evening with Basil Brush, 1975-76, which featured the Merv Thomas Orchestra.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas Dixielanders, 1960.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

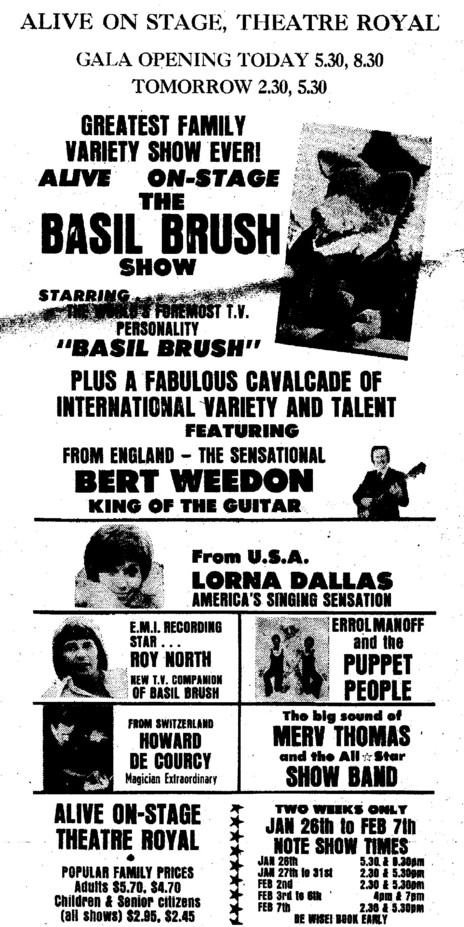

Advertisement for An Evening with Basil Brush, 1975-76, which featured the Merv Thomas Orchestra.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

English jazz trumpeter Kenny Ball tries out a tuba while jamming after hours at the Monaco club, Auckland, 1962. At right, Auckland musician Merv Thomas wonders if he'll get his tuba back.

Photo credit:

Neil McGough collection

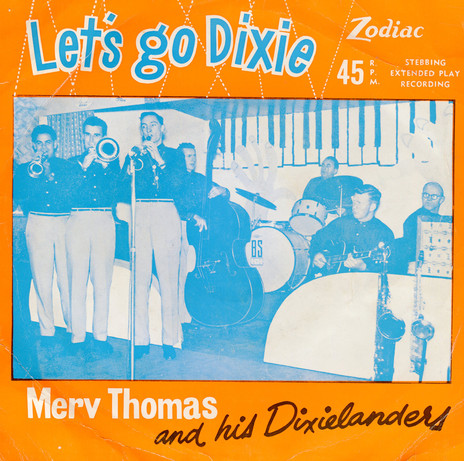

Merv Thomas and his Dixielanders - Let's Go Dixie EP (Zodiac, 1959).

Merv Thomas, Pumphouse, Takapuna.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas dressed for the part in The Great Kiwi Concert Party, a 1982 TVNZ musical comedy based on the story of the Kiwi Concert Party during Second World War.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the reunited Dixielanders – Hamilton 1st Dixieland Festival, 1992.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, left, at the Jive Centre, 1957. Among the other musicians are Frank Gibson Sr on drums, Bobby Griffiths on trumpet, and Bernie Allen on saxophone.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas socialises with the visiting Kenny Ball band, c. 1965.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, John Wilcox duo.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, 1932 Jazz Orchestra, Civic Theatre Cabaret, Auckland, 1998.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas on the helicon.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas with Lyn Christie (centre) and Pem Sheppard.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas, Neophonic Orchestra, 1968 National Jazz Festival, Tauranga.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas, left, performing at Mt Maunganui, c. 1955. In the jacket is saxophonist Pem Sheppard, who had recently encouraged Thomas to move from Whanganui to join the Auckland music scene.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Auckland Bandleaders at the Oriental Ballroom, Symonds Street, July 1962. From left: Bernie Allen, Al Patchett (Paget), Bill Sevesi and Merv Thomas

The Crystal Palace, Mt Eden Road, Auckland, 6 August, 1960. Bernie Allen at left with crossed arms, Merv Thomas holding trombone, and singing trio The Deuces (from left): Nuki Waaka, Robin Waata, George Tumahai.

Photo credit:

Rykenberg - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-B0752-29

On the set of One of those Blighters (1982), a semi-fictionalised tale of Taranaki novelist Ronald Hugh Morrieson.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas and the Bridge City Jazz Men, Mt Maunganui.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Merv Thomas in 1997, aged 66.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas - trad jazz Auckland Town Hall, c 1956/7

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Devonport Brass Band, 2005.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas (right) and the Prophets, Crystal Palace Ballroom, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

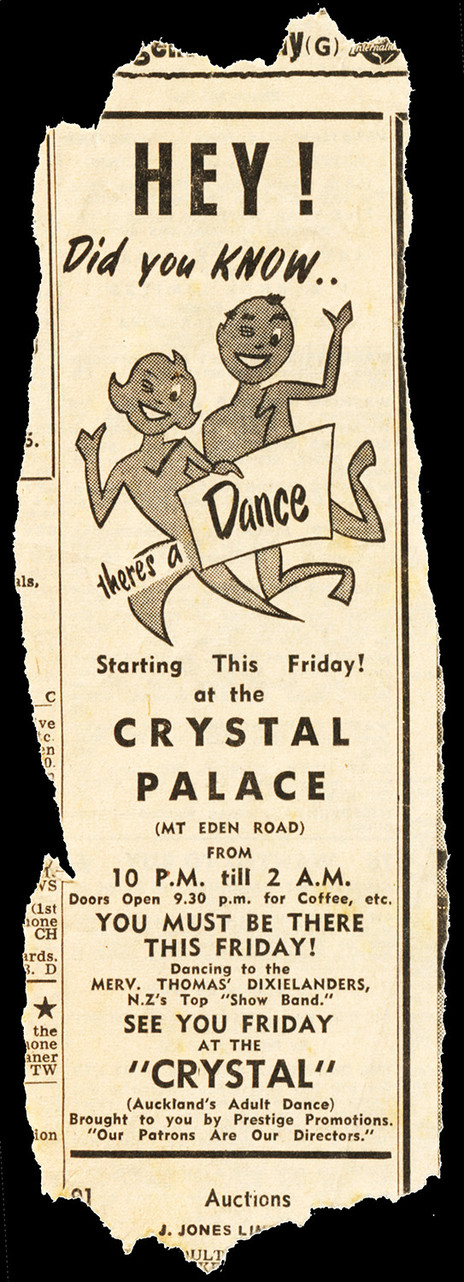

Advertisement for the debut of Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders at the Crystal Palace Ballroom, c1958

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Discography