Warren had a phenomenal memory and could recall bands playing in Auckland in the late 1920s: brass bands, soon to be followed by some of the earliest jazz bands in New Zealand.

By the late 1930s he was playing jazz professionally, and he heard a visiting swing band.

By the late 1930s he was playing jazz professionally, and he heard a visiting swing band. It was a revelation. Sammy Lee and His Americanadians showed him exactly the feel and force with which jazz should be played.

During the war, Warren was a key member of the “Swing Wing” offshoot of the crack Central Band of the Royal New Zealand Air Force. He then became a regular in Auckland’s two top dance bands, those led by Ted Croad and Epi Shalfoon.

By day in the 1950s and 1960s, he sold instruments at Begg’s and Atwaters, so he met all the leading players in town, and encouraged the aspirants. He toured in the backing bands of visiting musicians such as Trini Lopez (Louis Armstrong was top of the bill), Eartha Kitt and Shirley Bassey. At night, when not “having a blow”, he reviewed acts of all kinds for the Australian Music Maker magazine as its Auckland correspondent; he also reviewed jazz albums for the entertainment magazine Playdate.

He also inspired his nephew Philip to take up a career in the music business. When the teenager realised that he was no drummer, as Phil Warren he became New Zealand’s leading promoter and showman. Phil managed Johnny Devlin at his peak, and took the singer to Uncle Jim’s for dinner; Jim’s young daughter Louise was awestruck, and would later have a career as a Playdate writer and EMI publicist.

Throughout all this, and well into his 80s, Jim Warren kept playing professionally. His last big band was the 12-piece 1932 Jazz Orchestra, playing the swing of the 1920s and 1930s into the new millennium around Auckland – and even for the Crown Prince of Tonga. Warren was also its arranger. Why did he keep going? “Because of the pleasure and the challenge,” he told the Herald’s Jack Leigh in 1998. And, crucially, “because I like being around musicians, who are usually fun guys and like a laugh.”

To Warren, that was almost a mantra: it’s a saying he often returned to, always with twinkling eyes and a big grin. He sat on countless bandstands, alongside real characters, heard ridiculous stories and witnessed extraordinary behaviour. All the while, enjoying the rich, sumptuous sound of a big jazz band from the best seat in the hall.

When Warren was a young teenager, growing up in Kingsland, he mostly heard British dance bands on the radio playing the hits of the day. Among the bandleaders were big names such as Jack Hylton, Jack Payne, Lou Stone and Harry Roy. “Okay music, I suppose, good musicians – but some of the stuff was very ordinary.” It had to be quite square to get through 1YA’s programmers. “I never heard Louis Armstrong on the radio – Nat Gonella was the nearest it got to that. There was no black music, apart from I remember hearing Coleman Hawkins playing ‘Ghost of A Chance’ when I was about 14 [in 1932] – I don’t know whether I liked that very much. It was too different, too wild. The British stuff we listened to was very good in what they did – but it certainly wasn’t jazz.”

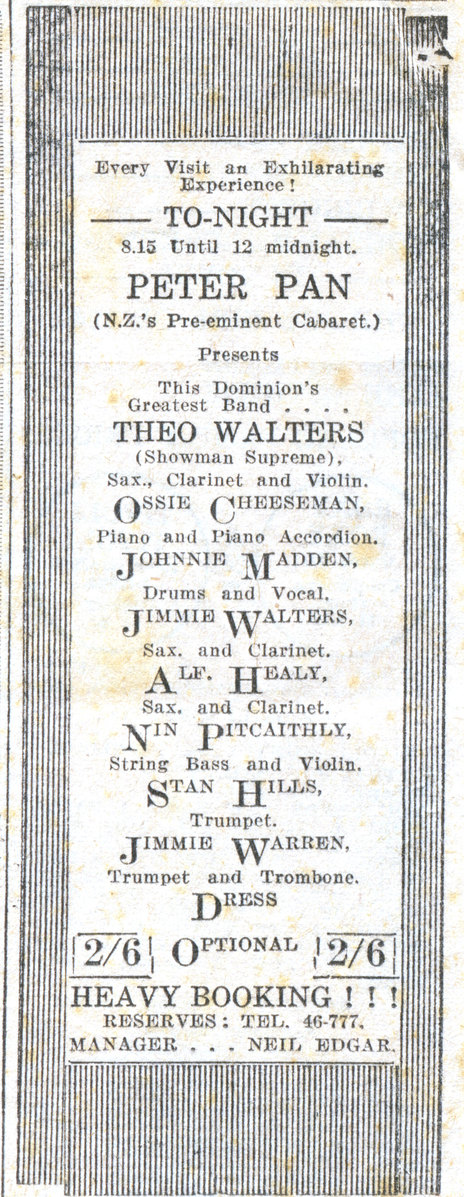

The first dance band that he actually saw was led by Lauri Paddi; it was one of New Zealand’s leading acts in the 1930s. For six months Paddi would have a residency in Auckland’s smart cabaret, the Peter Pan, then transfer to Wellington for a six-month stint at the Majestic. Warren was 16 when he went to a ball at the Peter Pan and heard Paddi’s band. “They were all in their bow ties, and Lauri had a special dinner jacket, with musical braid around the cuff. These guys were all playing and having a good time, having a laugh – and I loved the sound of it.”

Warren had been “fooling” with music for a few years, dabbling in the piano and flugelhorn. He went to join the Mt Eden Boys’ Band, and the bandmaster – “in those days they were very gruff, mustachioed characters with military backgrounds” – asked him to play something. Warren had practised ‘Drink to Me Only With Thine Eyes’, but hadn’t warmed up to get a sense of relative pitch. “I was in the wrong harmonic. I pressed down a B, and got an F# - it was a disaster, I sounded awful.” It was two or three years later before he got the courage to go back, and got the job of playing third cornet. Because of work commitments, he couldn’t attend many rehearsals, so the band asked for its cornet and uniform back.

He actually wanted to play the saxophone, but the cost – £58 – was prohibitive. He took a few old instruments to Atwaters and talked to Epi Shalfoon about trading them in for a trumpet. Shalfoon sent him downstairs to see Nolan Rafferty, who found an instrument that was playable and affordable. Warren would later play with Rafferty in the Air Force band, and in the early 1950s Rafferty became New Zealand’s star player in the dixie style.

Shalfoon recommended him to Johnny Madden, the “crooning drummer” at the Peter Pan cabaret.

Just before the war, Warren played in the Epi Shalfoon band. They were “lug” men, playing by ear rather than using charts. Shalfoon recommended him to Johnny Madden, the “crooning drummer” who led the band at the Peter Pan cabaret on Rutland Street. “I was green as, but they were great guys – so helpful – and I stayed in that band for nine months, then went into the Air Force.”

After two years in Fiji – playing the trumpet and piano when he got a chance – he returned to New Zealand and joined the Air Force Band in 1944. It was New Zealand’s best military band, and some of its players were also in a side group called the Swing Wing – a dance band. Many players in the Air Force Band later went on to help found the National Orchestra (now the NZSO).

He toured the Pacific, performing with the Air Force Band, not fighting. “No, fortunately,” he recalled. “No – we were the lucky musicians.” Nevertheless as the band island-hopped throughout the Pacific, just behind the war zone, he got an idea of what an ordeal the troops had been through. “We were travelling on an American ship, the Rochambeau, and oh boy, it was one of those times when you think, Well I’ve seen it and I don’t want any more of it. We were all packed in very tight, in awful accommodation below decks. There were two meals a day. The guys I felt sorry for were the black cooks, the mess men, working down in the heat in the bowels of the ship.”

The band played every night, often performing in parades in the afternoons as well. The audiences were American and New Zealand troops, and Warren found that the condition of each camp was a good indication of what the morale was like. A tidy camp, and well groomed troops, they were happy; a shabby camp, and slovenly men meant the opposite. This was also reflected in their response to the music.

After the war, Warren was a key member of the jazz scene. He recalled influential characters and friends such as the pianist Jim Foley (who ran a jazz show on 1ZB, and owned the hip record store above Vulcan Lane called The Vault); pianist John MacKenzie, who could play in styles ranging from Fats Waller to romantic ballads. He was a member of many small combos such as the Sunny City Seven, and as one of the Astor Dixie Boys, Warren recorded many sessions for engineer Noel Peach.

In Auckland, Peach was the backbone of the Wellington-based Tanza label, recording hundreds of sessions. “He was a great guy – very, very patient and very innovative. His wife Vida was always there to help him: they were good people. He wasn’t a musician but he had a very good ear. He was very capable at picking things up: sometimes we’d done a good cut and he’d say, ‘Not good enough – you have to do that again.’ I think he was very important in the music business.”

For six years from the late 1940s Warren played for Ted Croad, who kept the big band style going long after others had moved on, with residencies at the Orange Ballroom on Newton Road and the Trade’s Hall on Hobson Street. Croad’s band played at the Orange from 1935, and only retired when rock and roll took over at the Trade’s Hall in 1956 (it was renamed the Jive Centre). Croad paid well, so attracted the best players. Among them were pianist Crombie Murdoch, bassist George Campbell, his brother Lou Campbell on trumpet, and Jim Watters on saxophone. The drummer was Croad’s son, Ed Croad, who would marry the singer, Pat McMinn.

What Ted Croad lacked in musicianship, he made up with showmanship, Warren recalled in 2006: “He loved to dress up in his white tie and tails and conduct the band, but half the time he didn’t know what he was doing. We used to laugh and snigger. He’d be taking a band through a new piece – we had to be reasonably good readers – and Ted would be conducting and the band would finish and Ted would sometimes finish a bar later, or a bar earlier.”

The band scene was still busy in the 1950s, and Warren played with most of the key characters.

Running one of Auckland’s top big bands during the war – especially when the American servicemen were in town – meant that Croad made a lot of money, much of which he poured back into the band. He kept a sizeable band going longer than it was necessary or financially wise. “He could have made the same money with a band half the size,” said Warren. Croad played for ballroom dancers, and didn’t like it when jive dancing arrived in the 1950s. Over the microphone he’d say, “No jiving allowed” – so the crowd started going elsewhere.

The band scene was still busy in the 1950s, and Warren played with most of the key characters, such as Julian Lee, Crombie Murdoch, Jim Foley, John MacKenzie, George and Lou Campbell, and the Watters brothers Pat and Jim (who fought on the way home, arguing about who played a duff note).

Warren recalled long-lost Auckland cabarets and dance halls such as the Showboat – a floating dance hall at Mechanic’s Bay that was sabotaged – the Crystal Palace in Mount Eden, St Seps in Khyber Pass, St Benedicts in Newton, the Kit Kat in Newmarket, St Mary’s in Ellerslie, the Trocadero opposite the Town Hall … as real estate demands grew and dance fashions evolved, so too did these once-bustling places disappear.

The TVNZ series Radio Times in the late 1970s revived the pre-war big band sound, with a touch of English tea dance orchestra. The set-up imitated a live radio broadcast, with charismatic hosts played by Billy T James and Craig Scott. It was a breakthrough role for the multi-talented James, but for Warren it was a rare chance to play once again with his colleagues from the heyday of the big band. Among them were “name” players such as Crombie Murdoch, Merv Thomas, Neil McGough and Nancy Harrie.

“Watch those specks and spots boys, watch those specks and spots.”

Twenty years later, Warren’s last major gig was playing trumpet with the 1932 Jazz Orchestra, a 12-piece Auckland band with two vocalists. It favoured the swing rhythms and risqué songs of the 1920s and 1930s. Thomas, the first-call trombonist in Auckland for many years, was the musical director and Warren did much of the arranging. Their repertoire included 220 pre-World War II songs.

Of all the gigs that Warren played, one moment remains extra special. He was waiting in a green room to go on stage with Trini Lopez, when the artist on the top of the bill entered. It was Louis Armstrong, hero to almost every jazz trumpeter in the last century. The call came through – “All right, band on stage” – so his moment to meet his idol evaporated. “I always remember as we went past Louis he said, ‘Watch those specks and spots boys, watch those specks and spots.’ It stayed with me forever.”

Jim Warren died on 21 October 2016, the day before his 98th birthday. A discography of his recorded works, compiled by Dennis Huggard, has been published online by the National Library of NZ. Click on the words “Bk 10 Jimmy Warren.doc” and it will download automatically.