Marlene Tong

Sassy, pert and engaging, jazz singer Marlene Tong was the queen of the Auckland nightclub scene of the 1960s and has become more of a legend as time passes.

Friends and musicians who worked with her say her silky contralto and vocal stylings silenced audiences, such as those who saw her show with the Mike Walker Trio at the Montmartre on Lorne Street or at Bob Sell’s Colony Club.

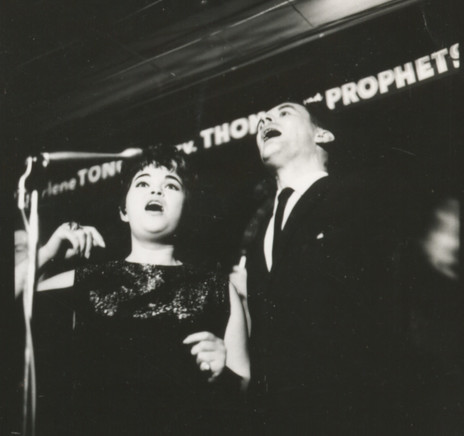

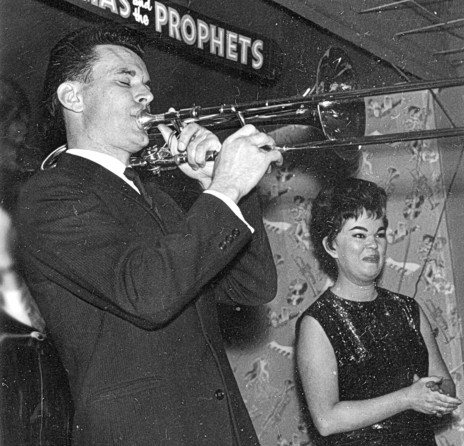

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

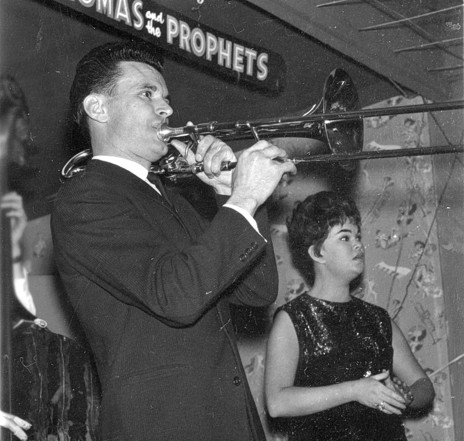

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas at the Crystal Palace, Mt Eden, Auckland

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, Auckland, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong performing with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, Auckland.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Marlene Tong.

Merv Thomas and Marlene Tong, Crystal Palace, 1962. Backed by the Prophets, the pair performed a Louis Prima/Keely Smith style cabaret act. “Marlene was great at that, she really was,” Thomas recalled in 2007.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

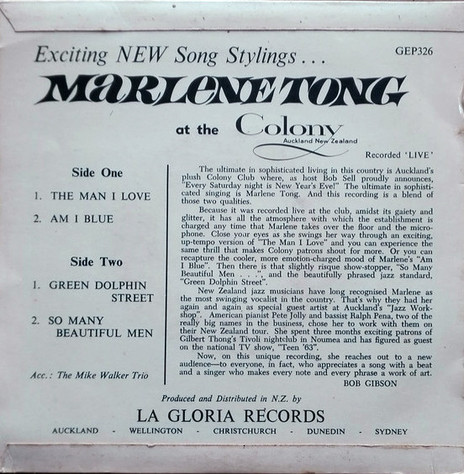

Marlene Tong at the Colony (La Gloria, 1963). A live recording with the Mike Walker Trio.

Marlene Tong at the Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

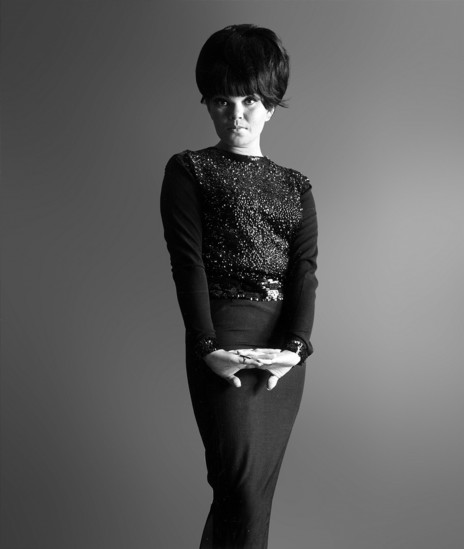

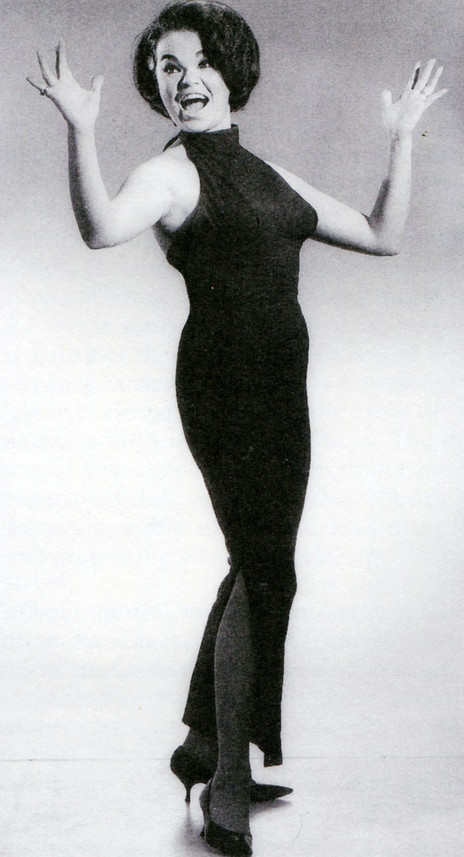

Marlene Tong: a promotional photo for a late-night session on 1ZB, January 1966.

Marlene Tong - a promotional photo from the collection of promoter Dave Dunningham.

March, 1963: Marlene Tong prepares for a WNTV-1 appearance, backed by the Mike Walker Trio Plus One (Mike Walker, Roger Sellers, Kevin Haines, plus Doug Jerebine. Tong sang standards such as 'My Favourite Things' and 'I Love Paris'. Directed by Brian Easte, the programme also featured Tommy Adderley.

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas doing their Keely Smith/Louis Prima act, Crystal Palace Ballroom, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

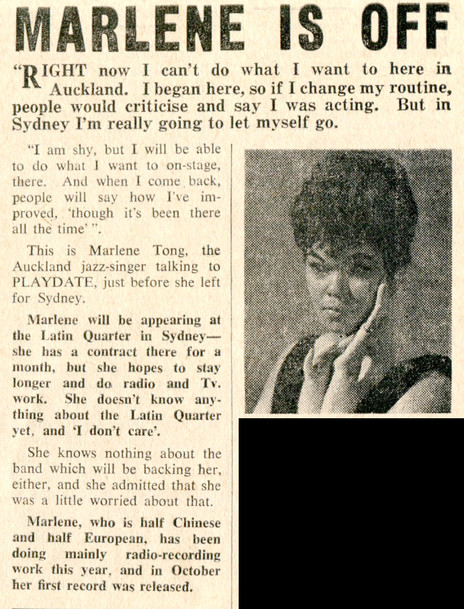

Marlene Tong in Teen Scene newspaper, 17 December 1963. She had recently made her Australian debut at the Latin Quarter, Sydney, performing a half-hour set which included 'I Feel a Song Coming On' and 'So Many Beautiful Men'. This comment surely comes from her manager, Harry M Miller: "Heads turned and eating stopped, while a capacity audience was completely won by this 5 foot 4 bundle of musical dynamite."

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas, with the Prophets, at the Crystal Palace Ballroom.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets; at left are Stewart Parsons and Morrin Cooper. Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong at the Colony, backed by the Mike Walker Trio – credits and liner notes (La Gloria, 1963)

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

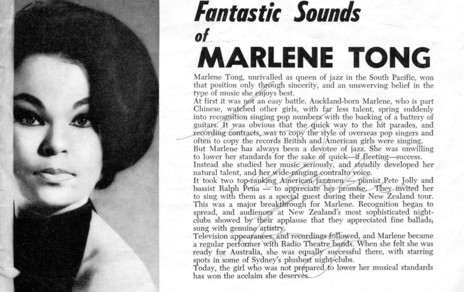

Autographed mid-1960s bio of Marlene Tong: "She was unwilling to lower her standards for the sake of quick - if fleeting - success."

Photo credit:

Simon Grigg collection

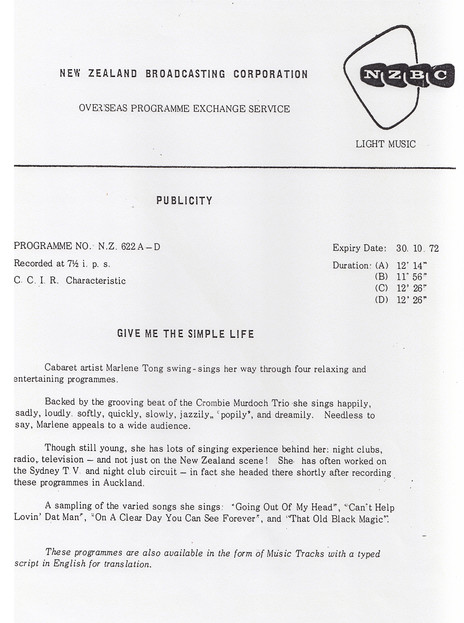

A presentation sheet for a NZBC radio session by Marlene Tong, made available for overseas broadcasts, early 1970s.

Photo credit:

Dennis Huggard archive

Listen to audio of Marlene Tong's EP, plus four extra tracks, recorded by Merv Thomas

Marlene Tong: a publicity photo for a NZBC television appearance.

Photo credit:

Dennis Huggard archive

Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962 (L-R): Bernie Allen, Stewart Parsons, Morrin Cooper, Marlene Tong, Merv Thomas, and bass player Bernie Hanssen.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong performing at the Crystal Palace, Auckland, with Merv Thomas and the Prophets.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Marlene Tong with Merv Thomas and the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962. From left: Bernie Allen, Stewart Parsons, Morrin Cooper, Marlene Tong, and Merv Thomas.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

Marlene Tong and pianist Lyall Laurent, Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas, Crystal Palace, 1962.

Marlene Tong at the Crystal Palace, Auckland.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas collection

Merv Thomas and Marlene Tong, Crystal Palace, 1962.

Photo credit:

Merv Thomas Collection

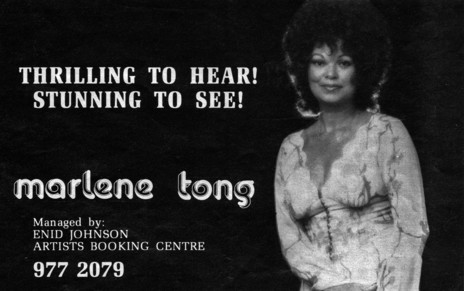

"Thrilling to hear! Stunning to see!" – Marlene Tong's management and bookings flyer.

Marlene Tong at the Colony - A-side label (La Gloria EP, 1963)

Marlene Tong: “She was a wonderful singer, had a great sense of humour and was always laughing,” recalled pianist Mike Walker. “Everything was just spot-on.”

Photo credit:

Redmer Yska collection

Marlene Tong is off to Sydney - a clipping from Playdate, December 1963

Marlene Tong at the Colony EP (La Gloria, 1963).

Marlene Tong and Merv Thomas, backed by the Prophets, Crystal Palace, 1962.

Discography

Labels: