Ebony

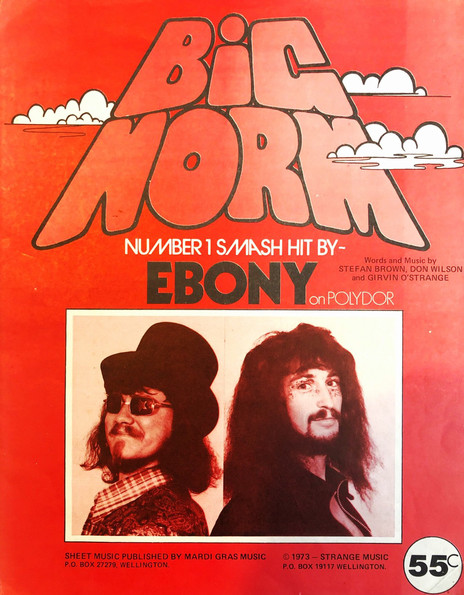

Ebony’s Don Wilson and Stefan Brown had dreamed of topping the charts since their early days with Stacey Grove in Upper Hutt. With runaway 1974 hit ‘Big Norm’ reportedly the fastest-selling single since ‘Hey Jude’ in 1968, they were well on the way to realising that dream.

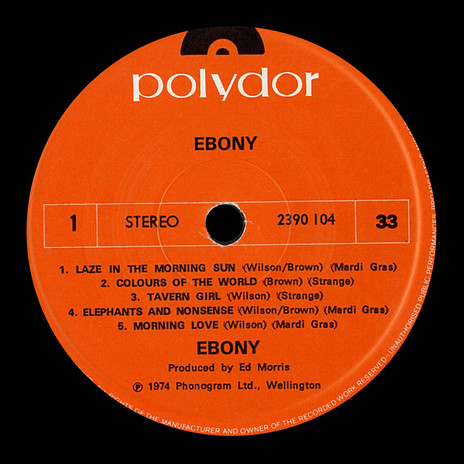

Ebony - side 1 label

Sheet music for Ebony's 'Big Norm'.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

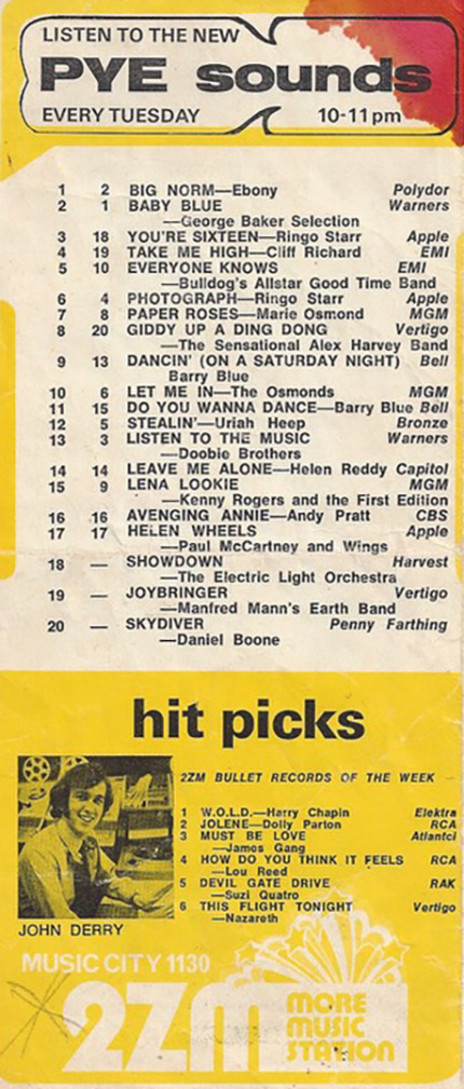

Big Norm tops the in-house chart of Wellington radio station 2ZM, 1974.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

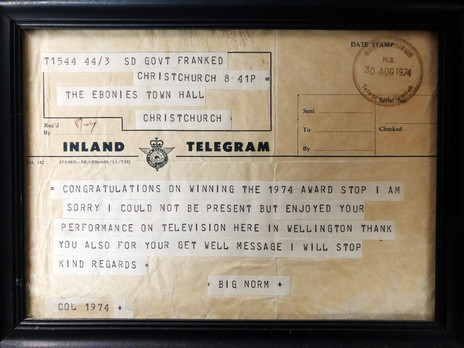

Telegram from Prime Minister Norman "Big Norm" Kirk congratulating Ebony on their success at the 1974 Rata Awards. Kirk died the following day.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

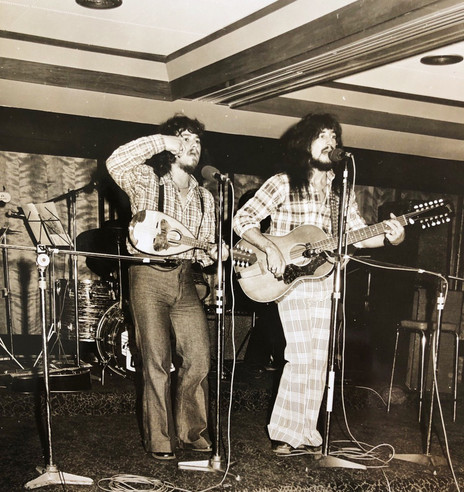

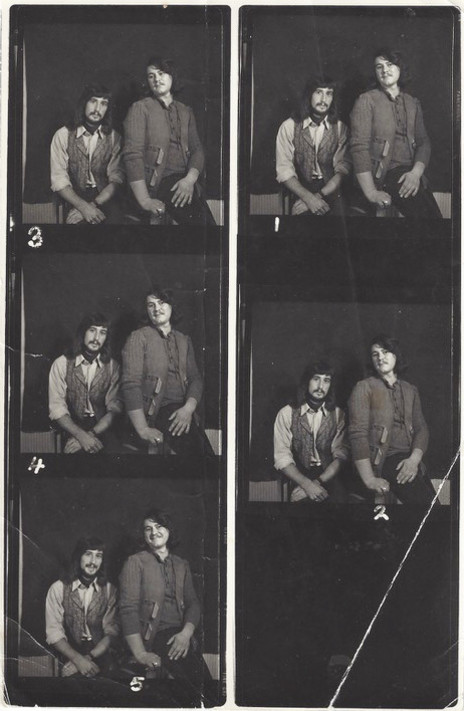

Stefan Brown and Don Wilson, Ebony.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

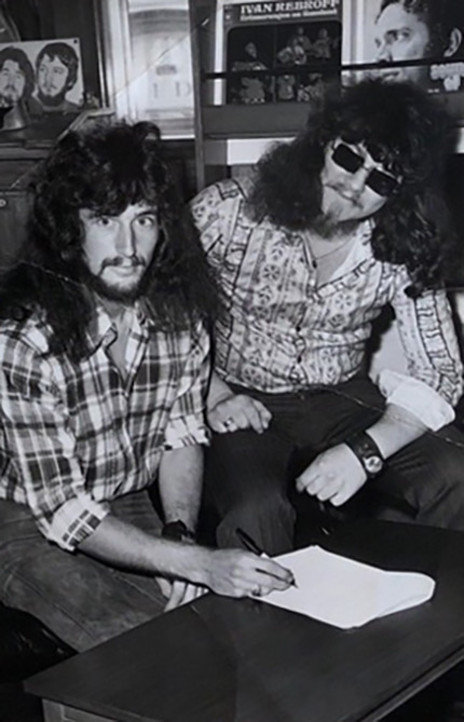

Ebony's Don Wilson and Stefan Brown signing their recording contract with Phonogram, 1973.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

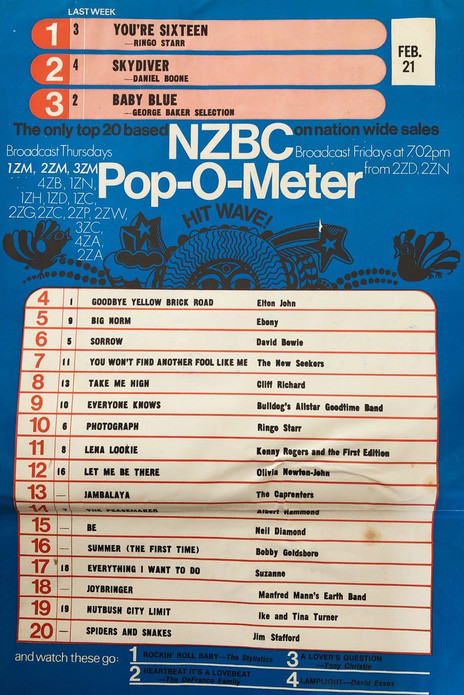

Ebony's Big Norm, at No.5 on the NZBC Pop-O-Meter, 21 February 1974. At No.1 is Ringo Starr's You're Sixteen.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

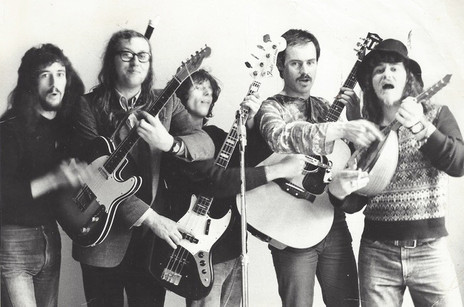

The expanded Ebony line-up. From left: Simon Morris, Don Wilson, Vic Singe, Stefan Brown, Alan Brown.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

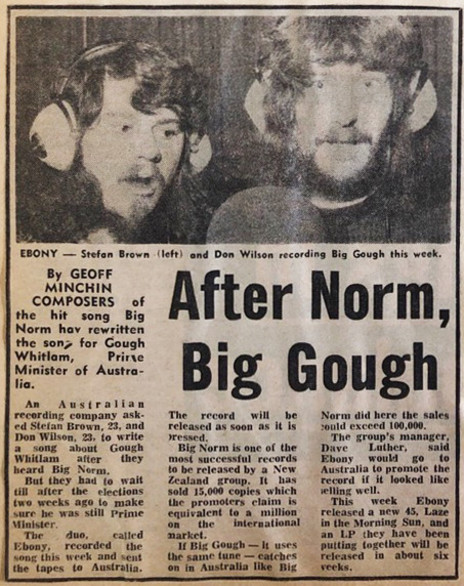

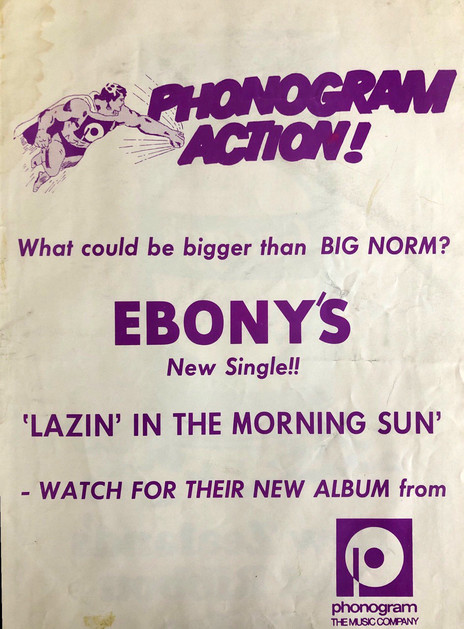

Following the success of Big Norm, Phonogram commissioned Ebony to record an Australian version entitled 'Big Gough'. The single was removed from the market after Whitlam threatened to sue.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

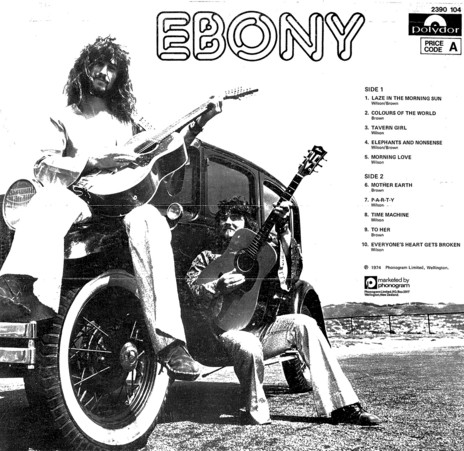

Back cover of the 1974 Ebony album.

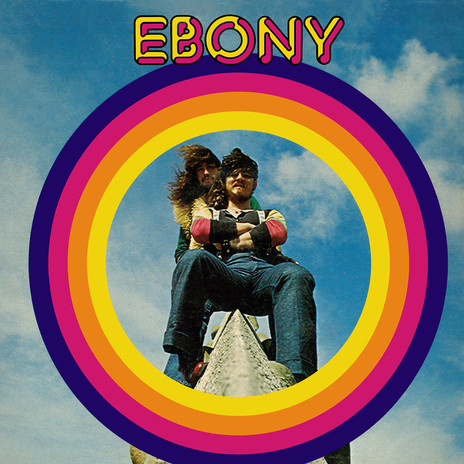

Ebony – Ebony (Polydor, 1972). Designed by Don McNeely of Supergraphics Ltd.

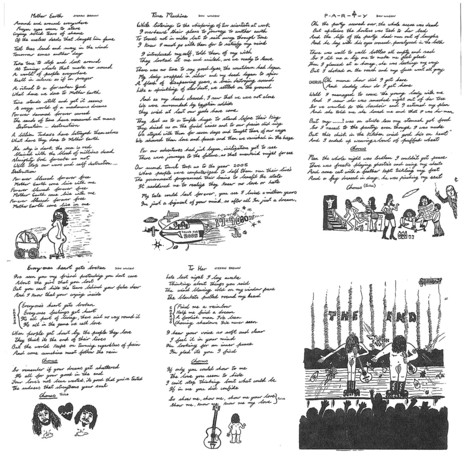

Liner notes ands lyrics, Ebony album, Phonogram 1974.

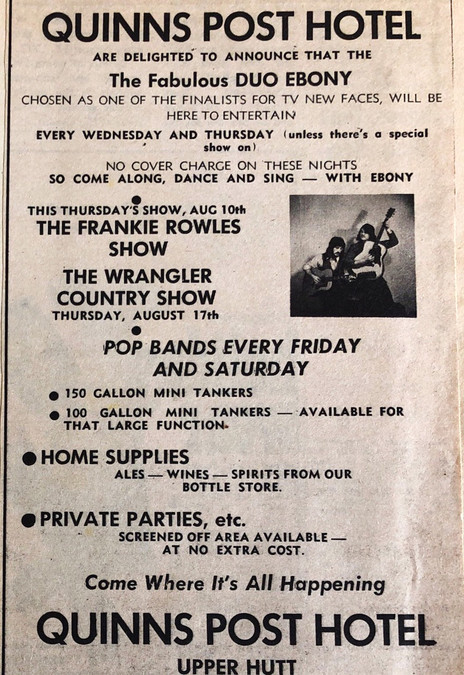

Advertisement for Ebony at the Quinns Post Hotel, 1972. Other attractions include Frankie Rowles, pop bands every Thursday and Friday nights, and 150 gallon mini tankers.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

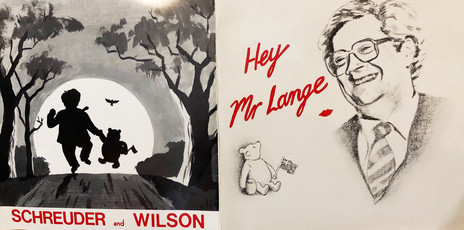

Schreuder and Wilson - Hey Mr Lange (Jayrem, 1984).

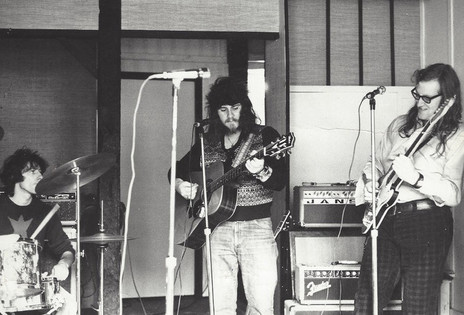

Ebony: Vic Singe, Stefan Brown and Simon Morris.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

The expanded Ebony line-up, from left to right: Vic Singe, Alan Brown, Don Wilson, Simon Morris, Stefan Brown.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

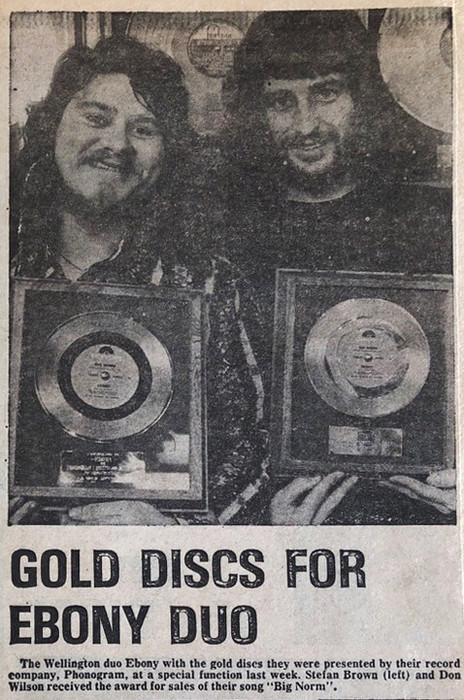

Ebony's Stefan Brown (left) and Don Wilson with their gold discs for Big Norm, 1974.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

Schreuder and Wilson - Hey Mr Lange (Jayrem, 1984).

Stefan Brown recalls 'Big Norm' on TV's The Nation, 2012

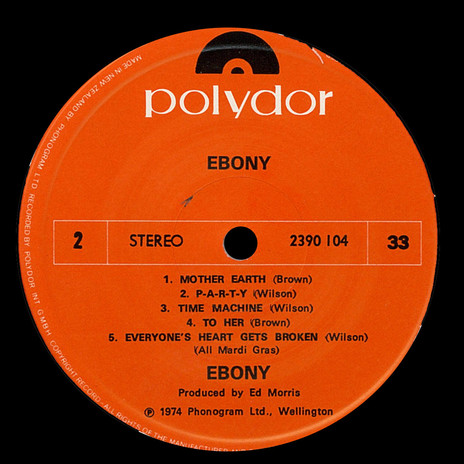

Ebony album label - side 2 (1974, Phonogram)

Ebony, from left to right: Don Wilson, Simon Morris, Vic Singe, Alan Brown, Stefan Brown.

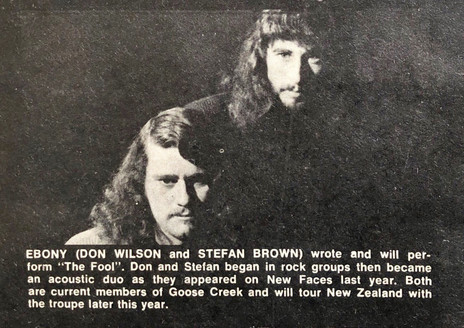

Ebony - a caption from the NZ Listener in advance of their 1973 appearance on TV's New Faces

The expanded Ebony line-up: Alan Brown, Simon Morris, Don Wilson, Stefan Brown, Vic Singe.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

The expanded Ebony line-up, clockwise from top right: Stefan Brown, Simon Morris, Don Wilson, Alan Brown, Vic Singe.

Phonogram advertisement for Ebony's 'Lazin' in the Morning Sun', 1974.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

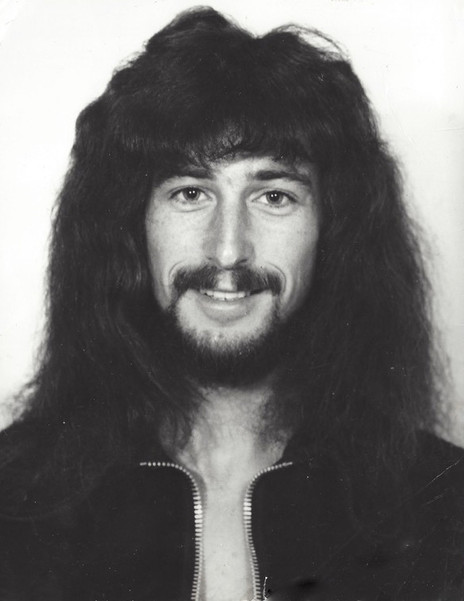

Don Wilson and Stefan Brown, 1973.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

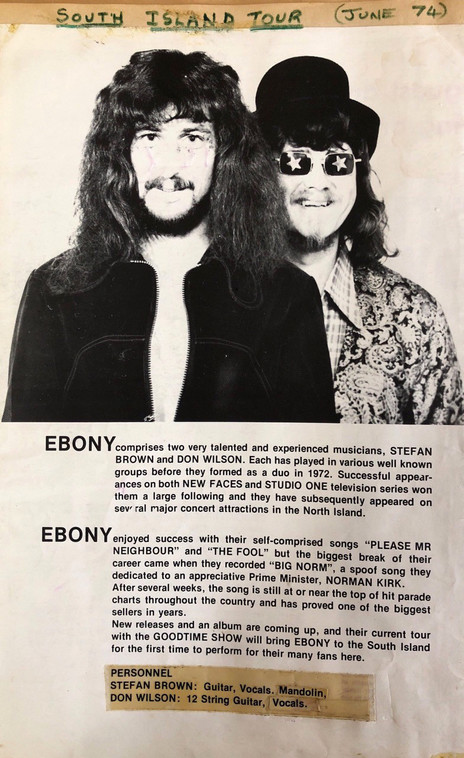

Ebony bio for a 1974 South Island tour.

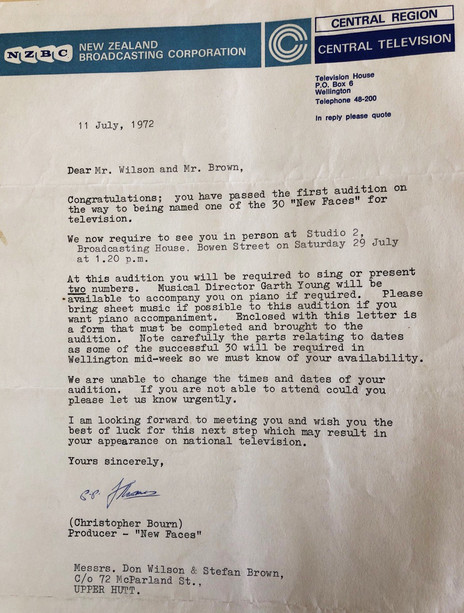

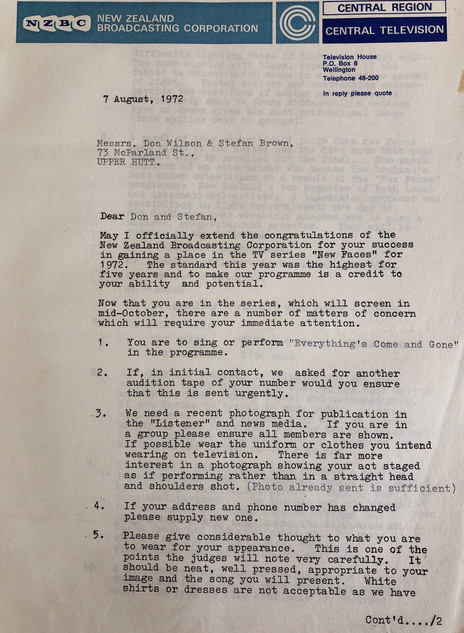

Congratulatory letter to Ebony from NZBC New Faces producer Christopher Bourne on passing the audition process, 1972.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

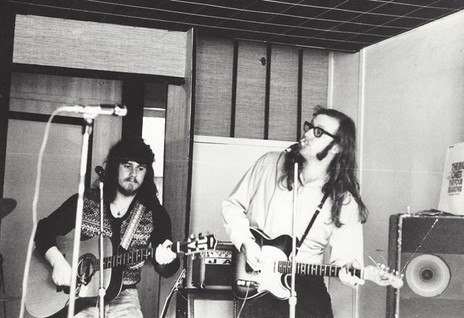

Stefan Brown and Simon Morris in Ebony.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

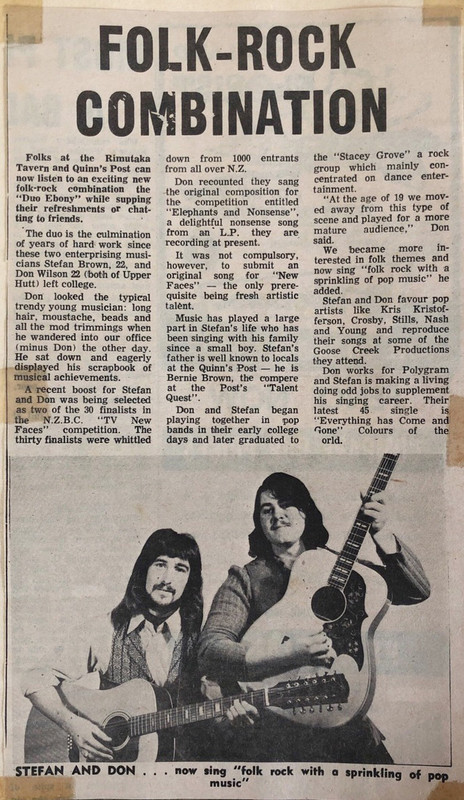

Ebony, a clipping - possibly from the Upper Hutt Leader - describes their forthcoming shows at the Quinn's Post, and the Rimutaka Tavern.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

Ebony's Don Wilson and Stefan Brown.

Congratulatory letter to Ebony from NZBC New Faces producer Christopher Bourne, confirming their appearance on the show, 1972.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

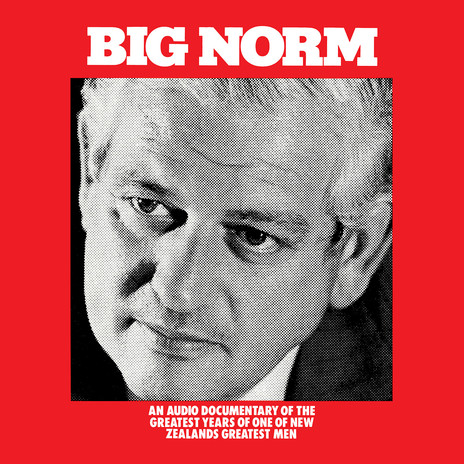

Inquiry - The Late Mr Norman Kirk (1974) featuring Ebony's hit single Big Norm.

Don Wilson, Ebony.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

Phonogram conference Queenstown 1974. L-R, backing band member, Don Wilson, Shona Laing, backing band member, Steve Gilpin (kneeling), Stefan Brown, Anne Picone, backing band member, Dale Wrightson.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

LP released by the Norman Kirk Memorial Trust. Ebony’s ‘Big Norm’ features alongside interviews and speeches.

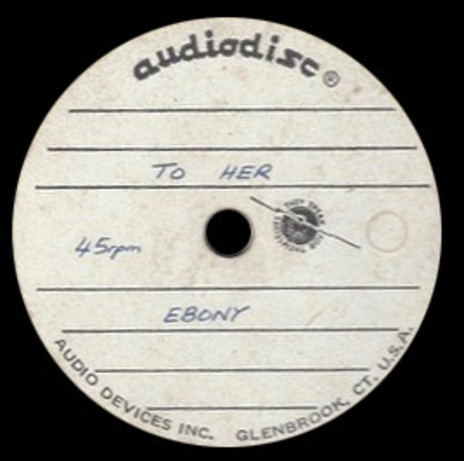

10" acetate of 'To Her' from the Ebony album.

Photo credit:

Stefan Brown collection

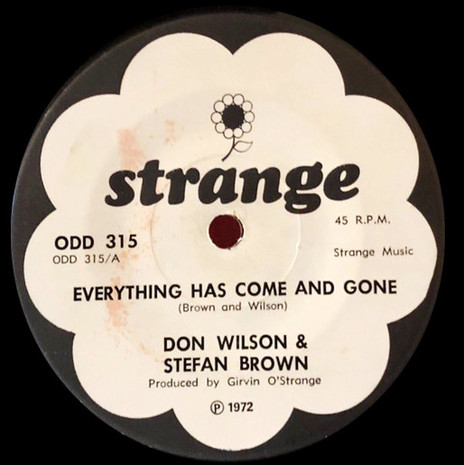

Don Wilson and Stefan Brown - Everything Has Come and Gone (Strange, 1972).

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

Liner notes ands lyrics, Ebony album, Phonogram 1974.

Ebony's gold record for 'Big Norm', 1974.

Photo credit:

Don Wilson collection

Trivia:

Phonogram commissioned Ebony to record an Australian version of ‘Big Norm’ entitled ‘Big Gough’. A threatened lawsuit by Whitlam saw the single removed from the market almost upon release.

In 1982 Wilson recorded a tribute to David Lange with Wellington musician Paul Schreuder.

Kerry Jacobson would later drum for Dragon from 1976-1983. In the mid-2010s Vic Singe drummed for Wellington's Rag Poets, alongside Clinton Brown and Carl Evensen of Rockinghorse

Labels:

Strange Music

Polydor

Philips

Members:

Don Wilson - vocals, guitar

Stefan Brown - vocals, guitar

Discography