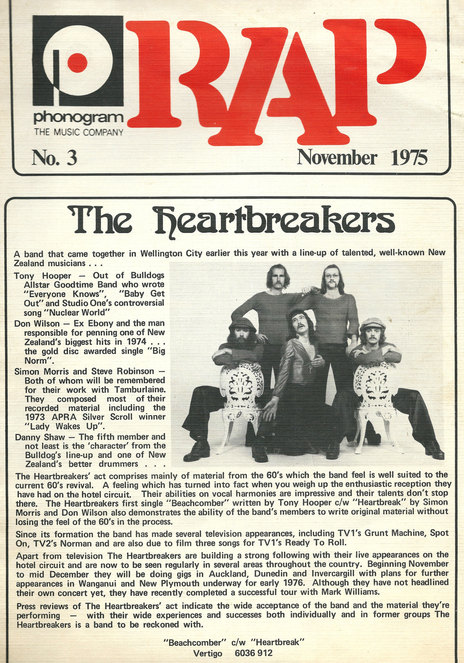

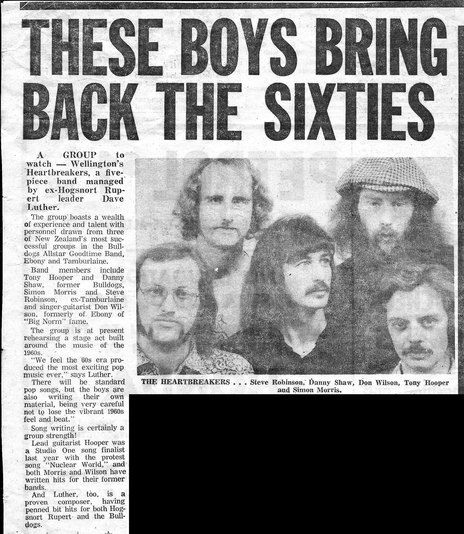

Appearing at the New Zealand Music Awards at the Christchurch Town Hall in 1974, Ebony found themselves in the company of Bulldogs Allstar Goodtime Band, with whom they had recently toured. With both bands calling it a day not long after, Don Wilson from Ebony got together with fellow guitarist/vocalist Tony Hooper and drummer Danny Shaw from the Bulldogs and called in bassist Simon Morris from the recently disbanded Tamburlaine. Morris had backed Ebony on their smash hit ‘Big Norm’, and been part of the band that toured promoting Ebony’s album. Guitarist Rob Winch completed the initial Heartbreakers line-up but was replaced by Steve Robinson, also ex-Tamburlaine, at rehearsal stage.

The Heartbreakers made an expedient decision to become a great pub band as opposed to the more financially risky endeavour of playing concerts.

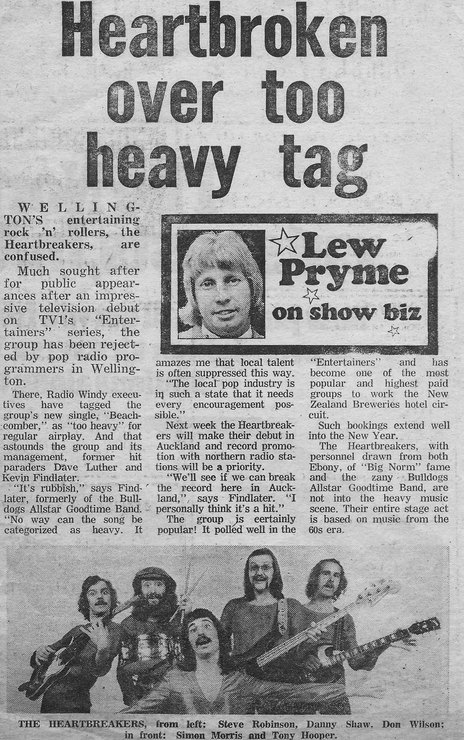

Initially the band was managed by former Bulldog Kevin Findlater and Hogsnort Rupert’s Dave Luther; in the latter stages Wellington manager Geoff Turner looked after the group’s affairs.

The band members' pedigree ensured not only immediate live work but also a recording contract with Ebony’s record label, the John McCready-helmed PolyGram. A&R manager Rick Shadwell worked closely with the band, placing them on the “cool” Vertigo label.

The Heartbreakers made an expedient decision to become a great pub band as opposed to the more financially risky endeavour of playing concerts, a route followed by such bands as Split Enz. In the 70s the famous/ infamous “pub circuit” provided a nationwide network of venues for live bands. They were adopted by and became the de facto house band of the Cricketers Arms in Te Aro, Wellington. Here they played literally hundreds of gigs between 1975 and 1977 with a residency every Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, except when they were out of town on tour.

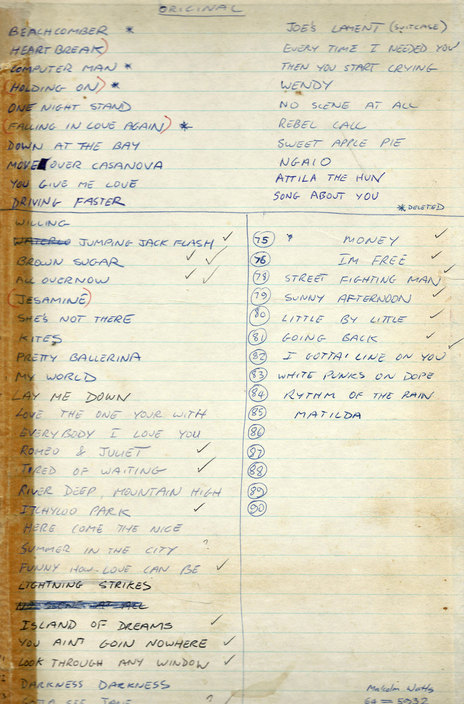

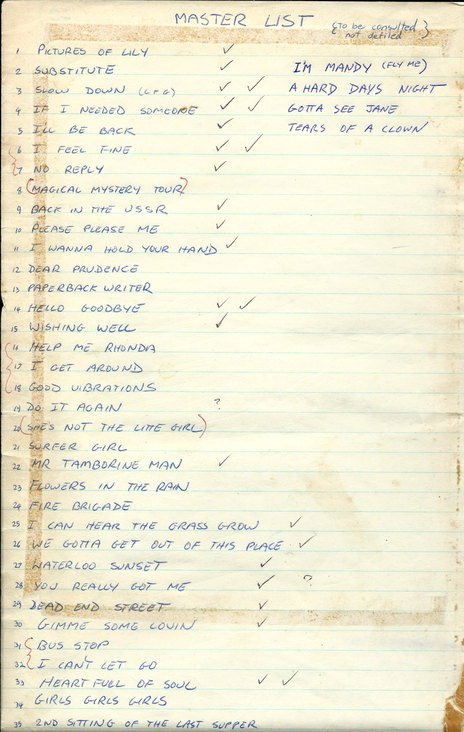

The Heartbreakers ethos was to keep the musical spirit of the 1960s alive at a time of rapid change in popular musical styles and tastes. The band members were all big fans of classic pop music so live shows included a crowd-pleasing combination of originals and covers. The covers included the Beach Boys’ technically demanding ’Good Vibrations’, 10cc’s ‘I’m Mandy Fly Me’, a four-minute version of Queen’s ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, and in a nod to the nascent punk/ new wave scene, The Tubes’ ‘White Punks On Dope’.

Morris was the group’s musical arranger and meticulously prepared set lists that gradually built the energy levels over what were often three-hour shows. The value of this was demonstrated one night as Morris recounts, “I was absolutely exhausted and instead of preparing a set list as I normally did we decided to play only requests from the audience. It was a disaster, the worst gig we ever played.”

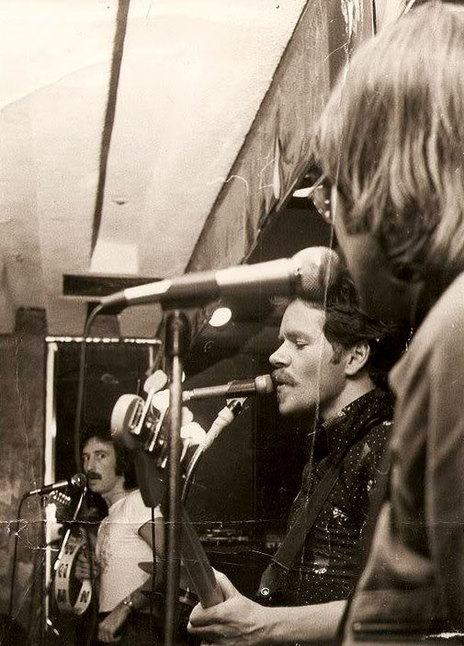

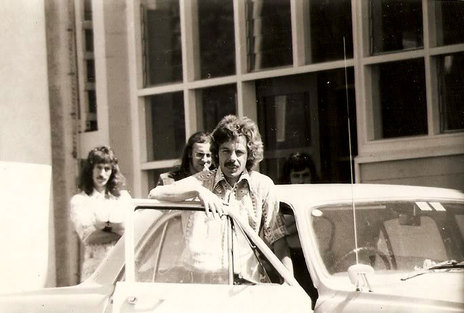

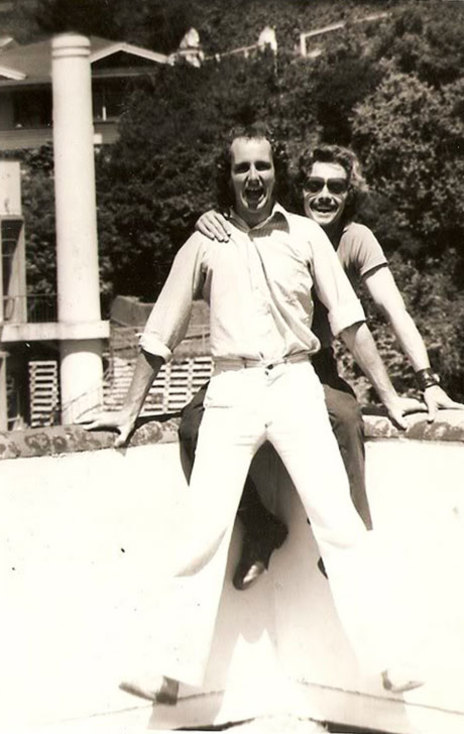

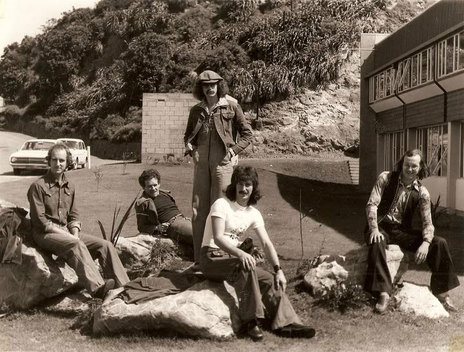

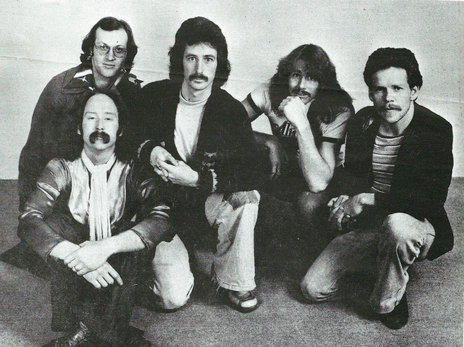

In appearance the band was very much a product of the early 70s, as opposed to the decade’s later, punk-influenced years: glam rock-styled outfits and long shaggy locks dominated. Morris: ”We certainly dressed in way that ensured the audiences knew we were the band!” Later member Nick Theobald notes: “You could say we were a band looking for a wardrobe!” One loyal Cricketers Arms fan even made special handmade shirts for the band in a vain attempt to improve their sartorial elegance.

Press clippings of the era report that the band constantly packed out The Cricketers Arms.

Press clippings of the era report that the band constantly packed out The Cricketers Arms. The punters were keen to enjoy the band’s repertoire mix with the added bonus of a zany live show and generous dollops of hilarity, provided in the main by the former members of the Bulldogs.

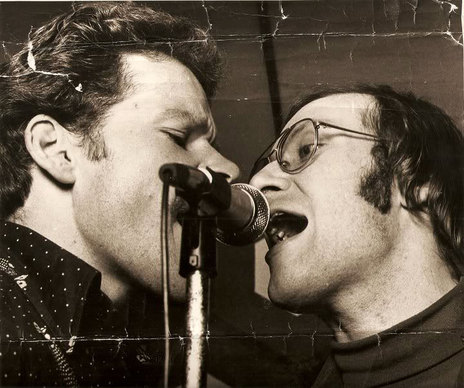

Wilson: “The band’s live performances were always laced with humour in all its guises from slapstick through to satire, irony, incessant puns, and lashings of sarcasm.”

“A common occurrence was when a member of the audience would approach the band in the middle of a song to request something, whereupon Simon would look down at the perpetrator with one extremely raised eyebrow, turn to the band with one hand in the air to motion them to cease playing immediately, and say ‘Yeeeeeessss?’ very loudly through the microphone. The whole bar was silent whilst all eyes were on the offender to see what he had to say – which as often as not was to make his request as intended without shame or awareness of his or her gross impropriety.

“I must admit too, to a constant habit of slipping in sometimes not so subtle childishly rude lyric substitutes which seemed to delight a large section of the audience, and usually resulted with Simon glaring at me and saying ‘DONALD!’ in a scolding tone.

“Visits to the bar from the police always prompted Morris to inject a piece of the ‘Z Cars theme’ into whatever song we were playing at the time.

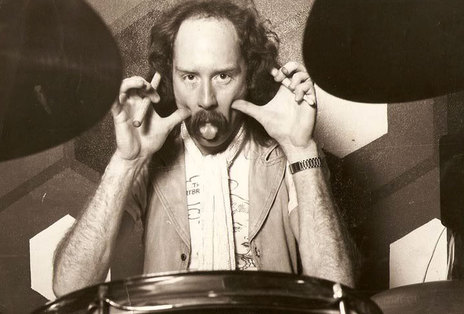

“And of course how could one forget Danny frequently getting off his drums and with great fanfare bending over towards the audience as he down-trou'd and brown-eyed them. These are some of the most horrified expressions I've ever seen in my life on the faces of people in the front row, especially one time when he had a particularly severe bout of haemorrhoids.”

“Another time I remember a group of intellectually handicapped folk had been brought into the Cricketers Arms, as they had a few times before being big fans of the band. On this particular night it was hot and they had maybe managed to sneak some alcohol.

“One of us took off a shirt to cool off and be a bit rock starry, and then the whole band did. Next thing half the audience followed likewise including the handicapped group who were by now essentially out of control and having the time of their lives. Mayhem ensued as the minders tried to gain control. If politically correct had been invented then, The Heartbreakers certainly wouldn't have qualified.”

Despite the seemingly light-hearted approach to gigs The Heartbreakers were extremely diligent with their rehearsals, the complex vocal harmonies being worked on for hours on weekday afternoons and in motel rooms on tour.

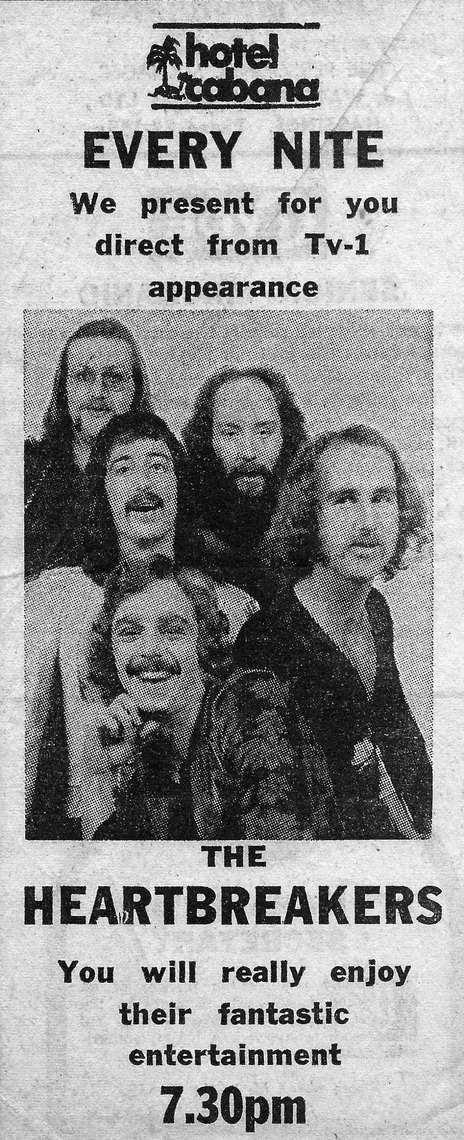

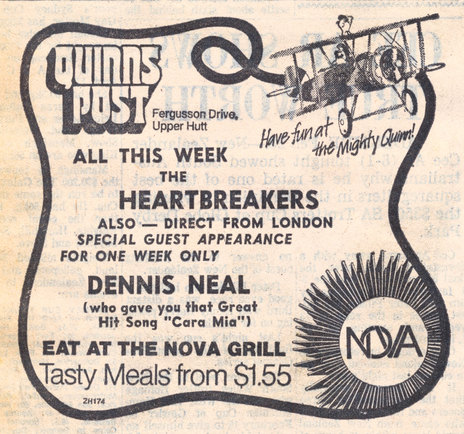

The out-of-town tours followed a typical breweries circuit of the day generally involving extended weekend (Thursday to Saturday) stints at pubs in regional centres such as New Plymouth and Christchurch. Venues for these gigs included the Awapuni in Palmerston North, the Rutherford in Nelson, Quinn’s Post in Upper Hutt, the Glenfield Tavern in Auckland and firm favourite of the band, Napier’s legendary Cabana.

Morris: “There was something really special, almost exotic about the Cabana. The audience was segmented into clearly identifiable groups: nurses, criminals, dope dealers, sailors, cops and groupies. We always had the most fun there, and were regularly invited to after-gig parties.”

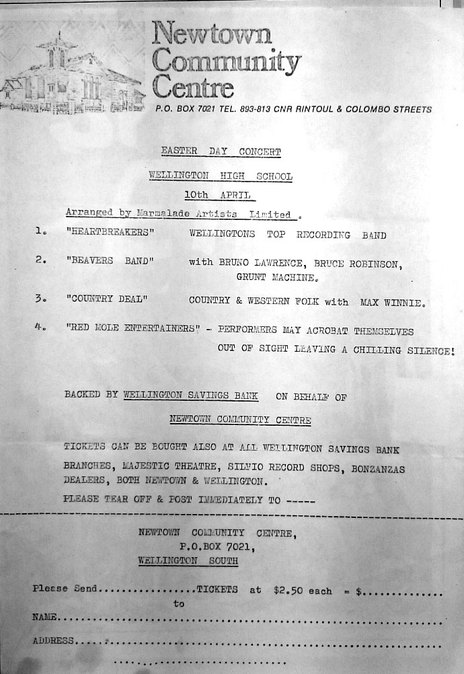

The Heartbreakers became something of a go-to band for Television New Zealand’s Ready To Roll and Radio With Pictures music programmes.

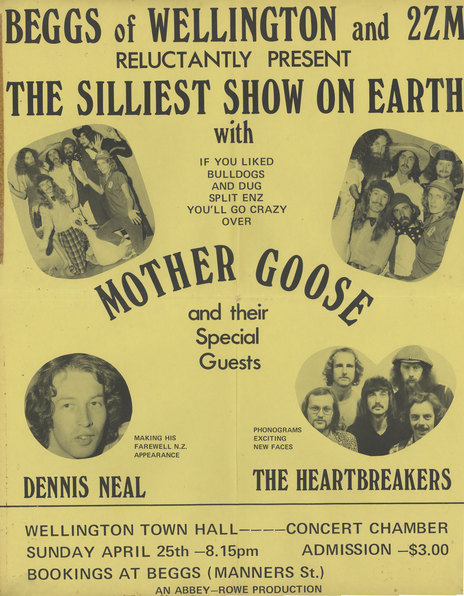

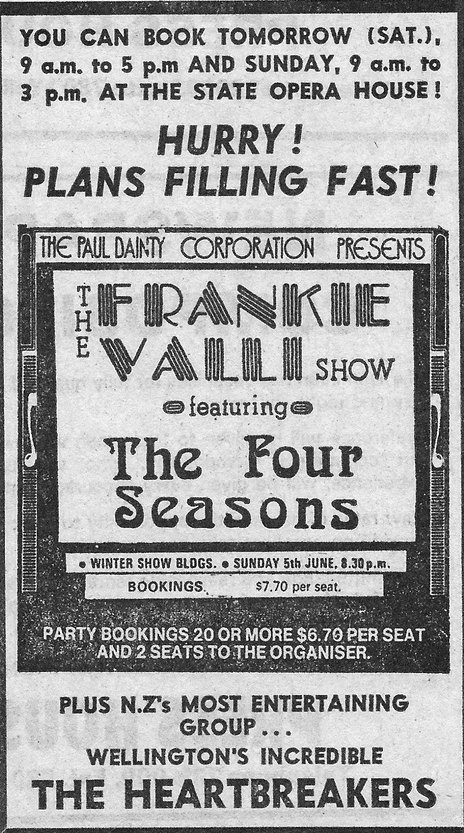

The Heartbreakers were also chosen to open for several touring international acts. Wilson recalls one in particular: “The Heartbreakers were support act for Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons at the Wellington Show Buildings. It was middle of winter, freezing cold. Frankie’s Mafia minders stole our heater from our concrete dressing room. They then gave us a much reduced PA system, and pulled the power plug just as we were finishing off our set with our hit, 'Romeo and Juliet', much to the chagrin of our fans. Not sure what they were insecure about!”

Being Wellington based The Heartbreakers became something of a go-to band for Television New Zealand’s Ready To Roll and Radio With Pictures music programmes. Their musical flexibility and vocal skills meant they were in constant demand and made many appearances, promoting their own singles and performing covers.

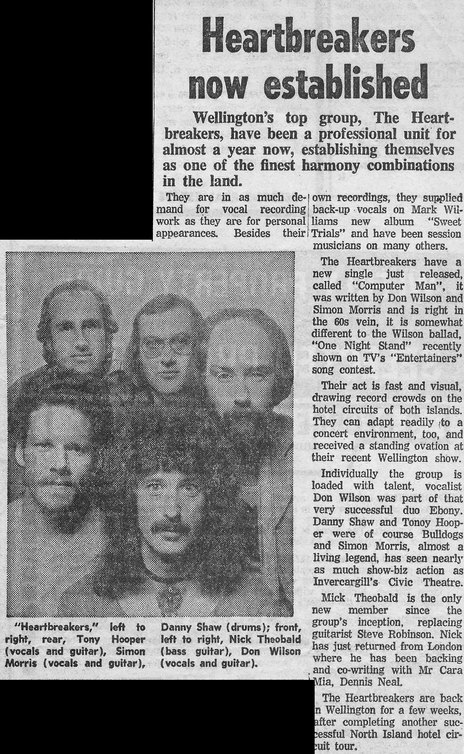

Early 1976 saw a line-up change with Robinson leaving to work at Marmalade Studios, replaced by bassist Nick Theobald, and Morris switching to lead guitar. Theobald had recently returned from his OE in England where he struck up a fruitful songwriting partnership with childhood friend Dennis O’Brien. Theobald recalls immediately clicking with the band and found in Hooper, Morris and Wilson, “three men with golden tonsils”, allowing the band to perform songs that required complex harmonies and arrangements. In this respect The Heartbreakers very much stood out from the pack on the pub circuit, with other bands covering more predictable fare such as tracks by the Rolling Stones and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Morris: “Essentially we were a harmony band with a really noisy rhythm section.”

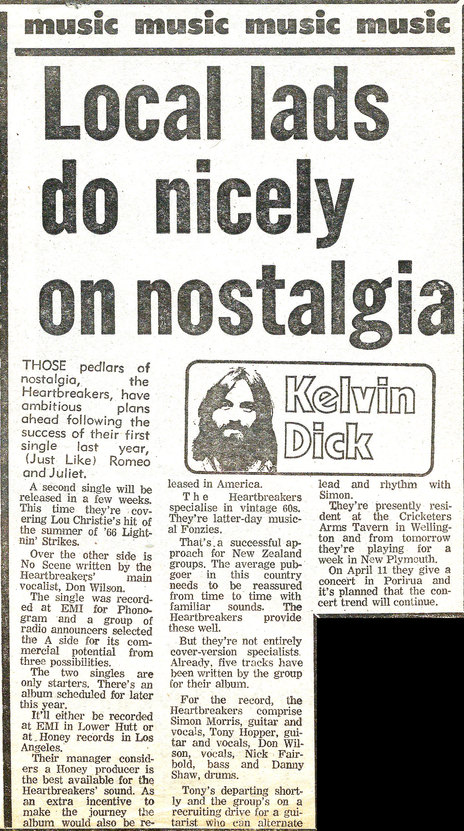

Throughout its three year history the band released a steady stream of singles. The first, featuring two originals in Hooper’s ‘Beachcomber’ and Wilson and Morris’s ‘Heartbreak’ was recorded at Radio New Zealand studios by John Fielding but garnered little support from commercial radio. Management were frustrated by Wellington’s Radio Windy deeming the single “too heavy” for their listeners.

Subsequent singles were recorded at EMI’s new studios in Petone with house producer Rick White.

Second single, ‘Computer Man’, although once again being largely ignored by radio, scored the band the “Best Pop Performance” award at the 1976 New Zealand Music Awards. Wilson recalls, “It was a very pluty affair at Trillos in Auckland and we were all flown up and wined, dined and made to feel special. I think we were reasonably well behaved too, except probably Danny.”

At the insistence of PolyGram the band held off recording an album in the hope of achieving a breakthrough hit at radio. The Heartbreakers loved playing together and would frequently regroup in hotel rooms after gigs to continue jamming on acoustic guitars, playing songs not featured in their live show. It was one of these songs that became their third single. This time radio responded favourably. ‘(Just Like) Romeo & Juliet’ achieved substantial success in the band’s home base of Wellington and rose to No.21 on the New Zealand Singles Chart.

Given the wealth of songwriters in the band, it was a bittersweet success of sorts for the band, breaking through with a cover of an obscure rock and roll tune originally released by American group The Reflections in 1964.

Wilson: “Following this success the label pushed us hard to record another cover, one none of us were keen on.” The band’s fourth single was their version of Lou Christie’s ‘Lightning Strikes’. Sadly this failed to emulate its predecessor’s success, the band turning back to another original for their fifth and final single in 1977. Hooper, Morris and Wilson’s ‘No Scene At All’ was backed by a second attempt at the band’s signature tune, ‘Heartbreak’. Once again radio proved a tough nut to crack and that proved the end of the Heartbreakers’ recording career.

Another line-up change saw Bill Beare replacing Tony Hooper for the band’s final months, but their time together had begun to run its natural course.

The band kept up a punishing live schedule throughout their existence. The constant demand for live shows ensured the band was one of very few in New Zealand whose members could survive from their earnings as live musicians. Band member earnings were supplemented by regular session work, particularly as backing vocalists, and usually at Marmalade Studios. It was in part the stress on their personal lives and just plain tiredness that led to the ultimate demise of the band.

Theobald: “There was certainly no bitterness or bust-up, I think we just decided we all needed a break.” They decided to take an extended break and regroup once batteries were recharged.

Hooper, Wilson and Theobald did join up again briefly as an acoustic trio playing upstairs at Flanagan’s on the corner of Kent Terrace and Marjoribanks Street. Later still Hooper, Morris and Wilson took up another residency, this time at the Romney Arms. Billed as The Romney Army this was a loose conglomeration that survived several years with a constantly changing line-up.

The Heartbreakers were a group of talented musicians that set out to enjoy themselves and succeeded. Morris: “When we were peaking, about a year before we broke up, I really was having the most fun of any band I’ve been in.”