I was a teenager with my head in the clouds and Dylan songs on my brain and guitar when I first heard this chorus on the radio:

“Gliddy glub gloopy nibby nabby noopy la la la lo lo/

Sabba sibby sabba nooby aba naba le le lo lo/

Tooby ooby wala nooby aba naba/ Early morning singing song/

Good morning, starshine …”

It was fresh, catchy and positive, and you couldn’t help but sing along. It was the same for every song on the soundtrack album from the new show in the States that everyone was talking about. My own experience in this show would literally change the course of my life.

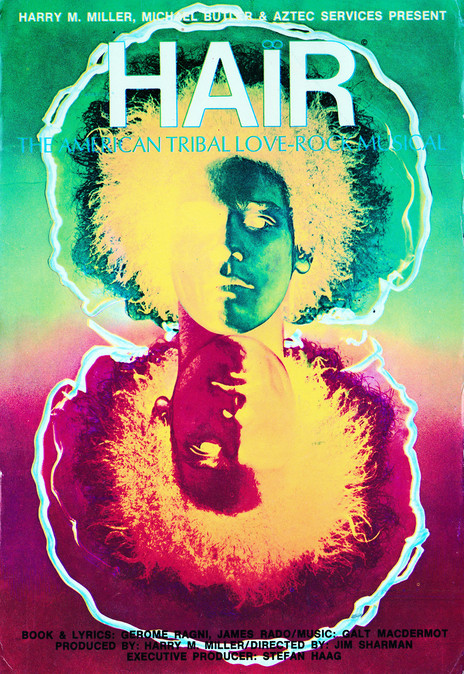

Promotional postcard for Harry M Miller's Australasian production of Hair.

Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical – written by American actor/director/playwrights James Rado and Gerome Ragni and Canadian-American film and theatre composer Galt MacDermot – was making news for all sorts of reasons. It was radical, colour-blind, gender-blind theatre based on youth culture and the revolutionary hippie movement’s values of peace, love, civil rights and sexual freedom as expressed on the colourful streets of San Francisco and New York.

This was the late 60s and Western society was in flux. Pervasive fears of nuclear warfare post-Hiroshima and Nagasaki had unsettled everyone. The international Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was in full swing and America had launched into its no-win war against Communism in Vietnam. On the ground in the US it was a time of massive unrest, with civil rights and gay liberation marches, anti-Vietnam War protests and sit-ins, and uproar about the draft, which “volunteered” 2.2 million young American men to fight via a ballot drawn from 25 million of eligible status. Hair rose out of this ferment.

Dark, attractive and thoughtful: Riccarton's Rosa Shiels joins the Hair tribe. The photo is from Rosa's appearance on the Popco TV show in 1972, singing 'Imagine'.

The creative troika of Rado, Ragni and MacDermot, each well-versed in theatre, crystallised these events and the emotions underlining them in a compelling, often visceral way. Through visual, musical and dramatic motifs voiced and acted by a motley cast of street characters, aka the “tribe”, the drama centres on a central tribe member who has just received his draft papers for Vietnam. Serious and satirical vignettes poke fun at and rail against the establishment, cry out heartfelt warnings about the situation, reflect on the basic goodness of humanity at its most innocent, and brand warmongering ideology and “fighting for peace” as innately hypocritical.

The creators challenge the medium of traditional theatre, too: the band is onstage instead of in an orchestra pit and the tribe ignore the proscenium-framed “fourth wall”, moving down into the auditorium to involve the audience directly by crawling under and across them, sitting on them, and mussing up their hair, their defences, their demeanour. The music is loud and contemporary with high-energy, almost non-stop dancing, and there is a nude scene, albeit brief.

When we were hearing about this show in New Zealand in 1968, Keith Holyoake was prime minister, Allison Durbin won the Loxene Golden Disc award for ‘I Have Loved Me a Man’, the New Zealand men’s coxed four won Olympic gold in Mexico, and the country was reeling from the Wahine disaster of April 10 and the 7.1M Īnangahua Earthquake of May 24.

In our southern Pacific backwater there was ongoing agitation and fretting about world and national affairs. The Ngā Tamatoa Māori renaissance was nascent and the left wing was rising. There was turmoil around gnarly issues such as class conflict, Māori rights, women’s and gay liberation, and anti-racist “No Māori, no tour” fury about the Rugby Football Union and its selection of all-white All Blacks for South Africa.

But from where I was sitting in Christchurch, it felt like we were at a considerable remove from such events. Now, as the post-quake rebuild continues apace, times they are a’changing in the city and surrounds, but back then the bone-chilling southern winds continued to blow against me and I was afraid hibernation would set in permanently if I stayed.

By 17, I was singing every free hour and keen to see the world beyond what I felt was a dull old conservative town. By the end of high school I’d abandoned classical piano lessons, had taught myself basic guitar and was singing in local folk clubs. The music from Hair had me in thrall, though, so I flew over to Sydney to stay with a friend and saw the show at the Metro Theatre in Kings Cross.

Rosa Shiels, Christchurch, pre-Hair.

Hair was everything it promised to be and more, with the added frisson of being in the buzzy city over the waves. I longed to be part of it all, but especially to sing in the show. For me, it had always been music ever since someone held a piano accordion on my knee when I was about two and I was fascinated by the feel of the keys and the peculiar sounds. My grandmother had played piano for silent movies and I inherited her piano, having lessons until I decided a guitar was more portable for parties. I learned songs from the radio and the 45s my friend’s working brother would bring home. Beatles, 50s pop, country, rock, folk – whatever. It was all music and Hair covered most of the bases.

Trouble was, I was about to start university. To what purpose, I was unsure, but once I was there lectures and my desultory studies filled in the hours between the concerts I was involved in for the University of Canterbury Folk Music Club and the odd outing with the Rock Club. I was also singing in the first iteration of Christchurch “head” band, Baby. Foldback was non-existent and I was singing my lungs out on ‘Jumping Jack Flash’, ‘Satisfaction’, ‘White Rabbit’ et al.

Not making much progress at uni, I took a year off to work while I thought about direction. Singing had to be at the forefront. I was leading an independent existence out of a Clifton flat in the inner-city by then and found a job in the Communist bookshop in New Regent Street around the corner from the Theatre Royal. The boss would disappear for long liquid lunches at the local, so I was virtually free to run the place. It had left wing literature (Frantz Fanon, Angela Davis, James Baldwin and so on) above the counter and more overt Communist tomes, such as Mao’s Little Red Book, below. Trotskyites, Marxists or Leninists would come in to buy their literature and argue their various sectarian standpoints.

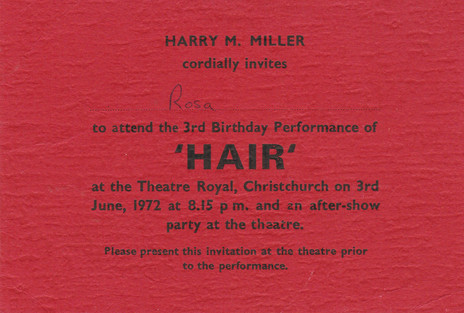

Show ticket for a session of Hair at the Opera House, Wellington, 1972.

One day everything changed. Advertising started, posters went up in the Theatre Royal and ticket sales were announced for the forthcoming season of Hair, the same Australian production I’d seen in Sydney. The promoters and producers, Harry M Miller Attractions, had been prosecuted for indecency in Auckland after premiering the show there – see accompanying story, Hair on Trial – but they had won the three-day trial and the Auckland season had been extended by some weeks. Joy of joys, it was coming to Christchurch. The closer it got, the more molto agitato I was. I could barely sit still.

City jazzman Pete Davey had a party at his place one night, and we heard that the show band had been invited. To get in to Pete’s old villa, with its wonderful mishmash of eccentric memorabilia, you had to blow the sax mouthpiece ‘doorbell’ – the rest of the sax was on the inside of the door. I got chatting with Bruce Morley, the late Auckland percussionist, who was in the New Zealand Hair band, and asked him if there were any cast vacancies. He wasn’t sure but introduced me to the director. I was out of luck that time, but two weeks later circumstances changed and I got the call to audition.

Inhibitions were the last thing they needed on that stage, so on the day I threw myself around and sang out a couple of pieces at full voice, hair flying and two left feet doing their best to be convincing. Somehow it worked. The pianist accompanying me was Mike “Spike” Walker, renowned piano man and long-time president of the Auckland Jazz Club. He was pianist and vocal coach for the New Zealand leg. I found out later that cast members would sneak in to the darkened auditorium and get a laugh watching the auditions.

Pianist and vocal coach Mike "Spike" Walker backstage.

Other Christchurch people taken on later were Reg Rutene, Graeme Jenkinson, Rex Graham (aka Graham Cleghorn), and Simon Morley. Other Kiwis in the tribe already included Elena Ashton from Auckland, who was touring with her young son, Sebastian, and the golden-voiced Lindsay Field in the central role of Claude. Others were from Australia, America, and England, and included triple-threat actors, full-time rock/soul/pop/blues singers, dance specialists and actors who could sing. Altogether there was a rainbow of backgrounds, talents, personalities and persuasions on stage and it all gelled into a fabulous, cohesive whole.

The first time I watched the show from out front I was cross-eyed with double vision from farewell partying with friends. After that night I was welcomed in and it was quick-fire learning from then on to get everything down – dance feet to co-operate, solos such as ‘Frank Mills’ or ‘Easy To Be Hard’ rehearsed for my turn to sing them, blocking, and so on.

When it came to the nude scene – about 30 seconds in semi-darkness lit by a whirring blue police light at downstage centre – newbies were elbowed down to the front as the band snickered from the sidelines. That was me, front row centre-stage in my hometown theatre on my first night in that scene, and I was horrified to see Miss Wynne, the primary-school teacher we’d all idolised as children, just five rows back. One night in some Australian city the crew decided to inject a bit of fun into the nude scene and released 20 or so colour-dyed mice as we all stood there naked. There were terrified shrieks and laughter, and a mad scramble to pick up our knickers before the house lights came up.

Hair 3rd birthday party, Theatre Royal, Christchurch. Watching before joining.

After Christchurch it was down to Dunedin for a short season before wrapping up the New Zealand run in Wellington with one of Harry’s flashy closing-night parties where the bubbles flowed and local VIPs were flattered, shmoozed, networked.

The stage mechanics undertook the massive packout and everyone else took leave of whomever they were staying with, ready for the hop across the Tasman. Today’s Customs would surely have made much more of it – us in our tassles, beads, bell-bottoms, tie-dye and patches, smoke haze hanging low – but I seem to recall we were eased on through quite quickly. Those were the days when you could still light up on board, and various smokeables perfumed the air-conditioning on all of our flights.

Rosa Shiels - BVs and dancing post-show.

We did six-week seasons in Perth, Brisbane and Adelaide then crossed Bass Strait for a final run in Tasmania. We stood out everywhere we went and a select few of us advertised the show on the road in the Hair-liveried tour cars. Brisbane was mosquito-central, heavily humid and wet, and it was obvious we were there under sufferance. It felt like an outback town that had grown into a big city overnight. One day we were walking down the street and some Queensland rednecks surrounded the beautiful Polynesian among us and spat these words at her: “Get back to where you come from, n****r!”.

Perth, isolated out there on the dry, hot wing of WA, felt like somewhere to nowhere. It was a giant relief to head on down to Cottesloe and Scarborough beaches and sink into the Indian Ocean. Likewise in tinder-dry Adelaide, sweltering from the red-hot desert centre at its back, we would take the city’s one tram 20 minutes down the line to Glenelg Beach.

Tasmania, with echoes so apparent of its painful and ugly colonial past – wholesale slaughter of its indigenous peoples and the cruelty visited upon the transported convicts – they seemed to saturate everything and gave the themes in the show even more relevance.

By the time the show finished for good in Launceston, some people had already jumped ship into other productions, such as Harry’s new production of Jesus Christ Superstar. Others returned to their places of origin and more headed to ashrams in India and elsewhere in pursuit of the godhead or the clues that aim you on the right spiritual path. One of our beloved became a Buddhist monk in Thailand and spent a couple of decades translating ancient Thai manuscripts into contemporary Thai.

The arrival of Hair in Wellington makes the Dominion's front page, 1 August 1972. Top row (L-R): John Wassens, Eric Weber, Michelle Rupena, Peter Snook, Maureen Andrew, Claire Raine. Bottom row: Kookie Eaton, Paula Maxwell, Linda Brotherton.

Those were heady days. Psychedelia was represented in our clothes and onstage costumes, music, and lighting effects throwing shifting prisms and rainbows. Many within and without the tribe were tuning in, turning on and dropping out in darkened rooms, incense burning and sitar ragas droning hypnotically in the background. It was the currency of the times. Some succumbed to psychotropic nirvana and others live on to enjoy it. Too many of our dearest ones were the earliest victims of AIDS and we continue to mourn them.

Many of the tribe from this original Australian production have gone on to strong showbiz careers. Michael Caton is well-known for his film and television roles in The Castle, Packed to the Rafters and, more recently, The Last Cab to Darwin. John Waters has been seen in multiple stage and screen roles. He inhabited the role of Darcy Proudman in TV’s Offspring until that character died, and his two-handed John Lennon music-theatre piece, Lennon – Through a Glass Onion, has been seen so far in Australia, New Zealand, New York, Edinburgh, London, Liverpool and Tokyo. Reg Livermore mounted several sell-out one-man shows in Sydney and went on to become a media personality there.

Marcia Hines in 'Abie Baby' in Hair.

Marcia Hines, for whom Harry Miller became guardian when he brought her out from Boston as a teenager to sing in the show, continues to shine in a solo and ensemble singing career. The late Sharon Redd, who returned to New York after her time in Hair, became a recording artist in her own right and backing vocalist for several people, including Bette Midler in the Harlettes.

Jonathan Banks, Hair Australia’s stage director and returning guest director for a season, is an American screen and television actor well-known for his standout award-winning or nominated roles as Frank McPike in Wise Guy and hitman and fixer Mike Ermentraut in both Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul. Well-known among the children who toured with us back then are Marcia’s daughter, Deni, an international singer and recording artist, and Miquel Brown’s daughter Sinitta, the British-based pop star, actor and media personality.

Hair - 'Black Boys Are Delicious'. From left: Rosa Shiels, Reg Rutene, Michelle Rupena, Robert Ellis, and Carole Fletcher.

The 50th anniversary of Hair in America was 2018, and 2019 marks the Australian production’s 50th. For our 40th we had a major gathering in Sydney that took many people many months to organise. Apart from catching up with people, the highlight was a start-to-finish sing-through of the show. Whether any of us, in or beyond our seventh decade, has the juice to organise a 50th is moot, but the tribal ties are ever strong and many of us remain in regular contact.

By the end of Hair in Launceston I was in a relationship with a musician in the band. Before going our separate ways we had a daughter and she is now a mother of two. I stayed on in Australia for 20 years until marriage to a long-time love brought me back to this land of power and plenty.

Closing night, Theatre Royal, Christchurch, 1972. Front row, from left: Rex Graham (in braces), Rosa Shiels, Linda Brotherton, Robert Ellis, Carole Fletcher, and Peter Noble.

As I look back I consider how being in this production links us to an extended tribal family that holds hands around the world. Hair websites continue to update international cast details, particularly from original productions, and despite the telescoping of time, the experience remains fresh in the mind. The show was also central in the expansion of my own family, changing the direction of my life, so that I am no longer the full stop at the end of our line.

Souvenir handbag from Hair, show provenance unknown. - Rosa Shiels collection

--

Read more: Hair on trial in Auckland, charged with indecency.