AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

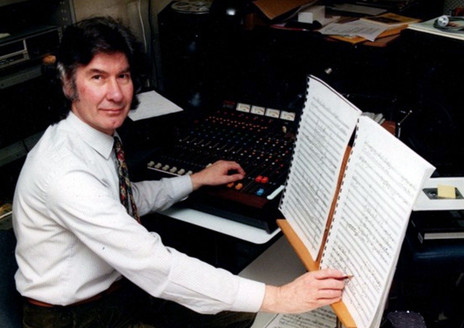

Michael Grafton-Green

He was hired as a tape operator, second engineer and disc-cutter, and in 1958 found himself in the studio working on Cliff Richard’s ‘Move It’, one of the first all-British rock and roll recordings. Most releases prior to this were covers of US songs.

Grafton-Green worked with a raft of established and rising stars including Cliff and The Shadows, The Hollies, Cilla Black and Shirley Bassey, Freddie and the Dreamers and The Beatles from their signing with EMI through to the famous Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Rd LPs.

After 12 years at Abbey Road, Grafton-Green came out to New Zealand to work at the Wellington HMV recording studios in 1970.

After 12 years at Abbey Road, Grafton-Green came out to New Zealand to work at the Wellington HMV recording studios in 1970. He recorded some of New Zealand’s top acts including The Quincy Conserve, BLERTA, Anna Leah, Rockinghorse, Alastair Riddell, Mammal, Shane, Corben Simpson and Mark Williams.

He helped usher in an era of new ideas and new technology as the old 4-track equipment gave way to eight and then 16-track and a wealth of new talent was bursting onto the scene.

“The 70s were a very good time for the whole of the music industry and therefore [it was an] exciting industry to be part of. I brought quite a few innovations from London with me. For the population at the time it was really stunning what was happening in New Zealand. They were really good world class bands and singers.”

Learning the trade

Michael Grafton-Green’s first qualification was in aeronautical and agricultural engineering, something his father, a London newspaper editor and film producer for J. Arthur Rank, thought would give him an edge when he recommended him for a job at Abbey Road Studios.

Grafton-Green was originally taken on as a cadet trainee at Abbey Road. Over 12 years he worked his way up to become sound engineer and cutting engineer. “On the big recording sessions there were always two engineers, one ran the tape machines and the sound engineer ran the desk. We worked together and I learned how the tape machines and desk were operated.”

He arrived in an era where there was a great crossover in musical styles. Sessions would vary from recording brass bands and baritone ballads to show songs on 78rpm and more adventurous rock and roll, pop idols and guitar-driven dance songs on 45s, EPs and LPs.

“One of the first people I worked with was Cliff Richard. He was very laid back but dedicated. He wanted to climb the ladder and make a success. Not in a ruthless way but what you might say a spiritual way.”

He watched as Cliff’s backing band The Drifters became The Shadows and created a stream of hits starting with ‘Move It’ (with Cliff, in 1959) and then recorded some “very exciting numbers” on their own as the era moved from acoustic guitars to electric.

As far as favourites go Grafton-Green said he had to be “very catholic in [his] musical tastes and just enjoy everything”.

As a studio engineer he had to listen carefully as the various musicians described the sound they were looking to achieve, which often required creative experimentation on what would today be described as relatively primitive equipment.

With The Shadows that meant trying to get the electric guitar sound as clean as possible. “They all had an input. Hank wanted a crisp sound and Cliff was very good in explaining what he wanted. What we were able to do with 4-track and 8-track equipment was quite astounding – it took a lot of ingenuity.”

Race up the Top 20

As rock and roll and pop began to dominate studio time, it became a fiercely competitive business. “All these people were vying for the top with their [45rpm] discs. Cliff might have No.1 this week and The Hollies might have it the next or The Beatles or Cilla. The Beatles were not always at the top.”

Grafton-Green worked with about 20 different performers trying to release hit singles – and then along would come an outsider like Adam Faith. “No one had heard of him before and then he recorded a couple of numbers that went straight to the top of the charts.”

He had a lot to do with “two fantastic vocalists”, Shirley Bassey and Cilla Black, fighting for top position on the Columbia label, with producer Norman Newell.

“Shirley Bassey was a terrific dynamic singer, really powerful. She was from Tiger Bay in Cardiff and her tough upbringing meant she knew the music she wanted to sing and she fought her way to the top.”

A big asset was her ability to constructively discuss with producers and engineers what she wanted “whereas a lot of artists who were a bit timid weren’t aware of capabilities and were slower to catch on.”

In a 2013 interview broadcast on Radio New Zealand, Grafton-Green recounted some well known history. Before signing up with Parlophone, The Beatles had already made a single for Polydor in Germany but were looking for a solid contract. After pitching to different record companies including Decca, feedback from A&R men was they were not quite up to it, until EMI recognised that “good, basic skills were there”.

Grafton-Green said the Fab Four were at first overawed by the three huge studios and 120 personnel running around at Abbey Road. “They quickly learned that one was looking for good playing, presentation and music. They couldn’t get away with just the rough stuff they were doing in the clubs. It had to be polished and smart ... good entries and finishes.”

Keep it in tune boys

In his polished English accent, Grafton-Green explained that producers insisted on “clear playing” and of course the instruments had to be in tune. “A lot of the bands were not in tune. We used to stop in the middle and say for goodness sake tune up, it’s not right.”

He said a big part of the job was working closely with the artists to determine which of their song and musical ideas could be accomplished on the often primitive 4-track equipment that was being used in the beginning.

He conceded The Beatles were a different story, having done a lot of club and studio work previously. However, producer George Martin had to work them hard before recording started.

“The first thing George did, and I think this is one of the saving graces of the Beatles and why they were so successful, was he just sat with them on the floor of the studio for two to three days to get the tuning sorted and the way the guitars were played where it was too rough or not clean enough.”

George Martin could play the guitar himself and often ran through and explained different techniques and wouldn’t start recording until he was happy with everything. “It was George who cleaned their act up and got them really professional.”

Grafton-Green worked on many of The Beatles sessions and would often interact with them during breaks or when playing back the tapes.

Grafton-Green worked on many of The Beatles sessions and would often interact with them during breaks or when playing back the tapes, and would respond when they asked for comment.

He reckoned he had a good rapport with most of the musicians. “They are very sensitive people, particularly when it comes to recording and being photographed. You had to be encouraging, if you weren’t they could go into a spin and at times become hostile. If you said something you had to put it in a constructive not a negative way.”

Distressing tensions

The art of being an intimate part of the studio team was to find a way to settle people down when there were arguments or tension in the studio. There were good days and bad days, particularly if The Beatles had been out playing or partying the night before. “There was a bit of infighting between John Lennon and Paul even in those early stages around different ideas. There was a pull between different ways of doing things.”

Paul, he said, “... went for the more cosy type of song that was warm and would appeal to anyone while John would go for a more avant-garde songs, and ways of doing things that didn’t always appeal and therefore you would get this tension.”

The albums Grafton-Green had most involvement with were Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Road, where the producer and engineers had to work closely together.

He was involved in a range of tasks, from tape editing to specialised backroom jobs including transferring the master tape onto vinyl through disc cutting.

“This machine was cutting a groove in an acetate and sucking up the chips in a continuous stream with a diamond cutter in the recording head. If the cutter got too warm it could cause a little fire and everything would go up in smoke and you’d have to clean up and start again. It was scary stuff.”

Technology timewarp

After a spell with the BBC transcription service recording concerts with many of classical music’s great orchestra and conductors, he accepted a position with HMV studios in Wellington in late 1969, where he was expected to work with outdated equipment, including two 4-track recorders and an ancient mixing desk.

A cry for help was made to EMI in London, and a decision was made to deliver a big Neve mixing desk with sliders and effects channels and an 8-track recorder that could be upgraded to 16-track.

When this new recording equipment arrived Grafton-Green was among those who unpacked it and assembled it in the control room.

Among the first projects he worked on in New Zealand was 'Wahine', a song about the Wahine disaster written and sung by Anna Leah, and produced by Peter Dawkins. He worked with a variety of artists including Allison Durbin, Desna Sisarich, Quincy Conserve, Lutha, Rockinghorse and Mark Williams, often alongside producer Alan Galbraith.

He worked with a variety of artists including Allison Durbin, Desna Sisarich, Quincy Conserve, Lutha, Rockinghorse and Mark Williams, often alongside producer Alan Galbraith.

In February 1972 Grafton-Green was overwhelmed when a bus load of hippies and their families and hangers-on took over the studio. This was the BLERTA phenomenon, and it required all the skills he could muster to settle everyone down and set up for the ‘Dance All Around the World’ sessions.

“We finally got the session going after a lot of pushing and arguing. It was an expensive project for EMI to take on, because of the downtime in getting the musos settled, setting up the equipment and going through the new numbers they wanted to record, which they hadn’t rehearsed of course.”

He said it took “quite a few takes” to get ‘Dance All Around the World’ down but “once they got into it, it was really fantastic and a lot of fun. If you have people who are uptight you don’t get good music out of them.”

Sleeping in the studio

Preparing for Get Up With The Sun, the second solo album for BLERTA lead singer Corben Simpson, was also something of a revelation. While astonished at the raw talent of the singer-songwriter, he was stunned at some of his requests and how long it took to get him settled in.

“He was an extraordinary acoustic guitarist but he said he needed to get into the right mood to be creative and bring his own bed to sleep in the studio overnight to get the feel of the place.”

He insisted he’d be ready bright and early the next morning but when Grafton-Green arrived it was clear the star performer hadn’t slept that well.

By mid-morning it was all on and five tracks with Corben singing and playing were recorded in quick succession with backing added later. “He was wonderful to work with but such an independent guy.”

Working with Alastair Riddell challenged the sound engineer to show some of the tricks of the trade from his Abbey Road days, as he and producer Galbraith made full use of the now upgraded 16-track recording equipment. Having the singer sound miles away or “ethereal” yet still retaining clarity required a certain amount of walking while singing but was used to good effect with rock groups Lutha and Rockinghorse. “Rockinghorse were always into trying new microphones and doing experimental things.”

One of the independent projects he worked on was with Ebony, a group managed by Edd Morris and first released on his Strange label. Their most memorable outing was a tribute to Prime Minister Norman Kirk, who died in August 1974, six months after the single ‘Big Norm’ hit the No.4 spot on the national charts. Grafton-Green also engineered the Mantis album Turn Onto Music with Edd Morris (as Ed Morris) producing.

Initially the role of technician, engineer and producer were completely separate. Over time they became integrated with the producer taking on much of the responsibility. The emergence of digital technology did away with the need for tape splicing or making vinyl acetates to produce a recording.

Despite his time in the pop industry, Grafton-Green’s real passion was classical music. In 1976 he moved to the Radio NZ Concert Programme as music producer, working in Wellington and Auckland with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra.

From 1994 to 2001, he worked in Canberra at the Australian National University School of Music as senior technical officer and music producer. He pioneered direct-to-disc CDs for student graduation recitals, handing them their CD at the end of the concert.

His sound consultancy saw him working both sides of the Tasman, retrieving and restoring old reel-to-reel and cassette tapes, vinyl and film for archival purposes and film productions.

Grafton-Green, described by his peers as a gentleman, a perfectionist, with “an almost ruthless attention to fine detail”, died in Canberra on 8 October 2014, aged 79.

Alan Galbraith - making records at HMV and EMI

Truth and legend – The HMV and EMI recording studios and pressing plant

HMV

EMI

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air