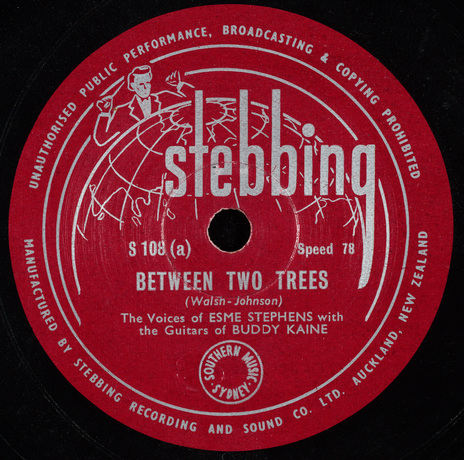

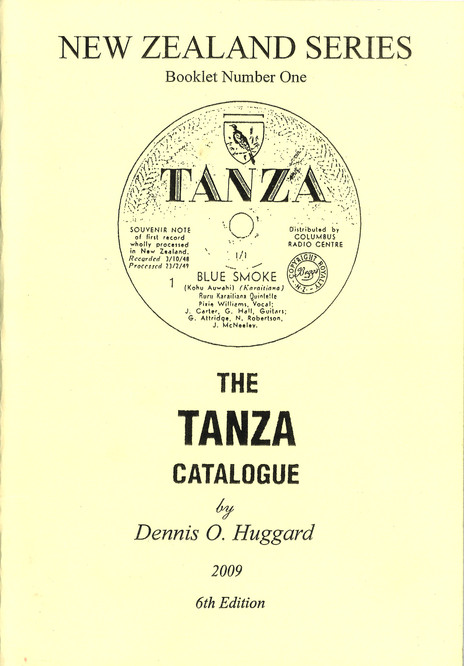

As well as these clippings, he collected New Zealand music on 78rpm discs, acetates, vinyl discs, reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes, CDs, mini discs and MP3s. With some advice from the Alexander Turnbull Library’s music librarian Jill Palmer, he cross-indexed every item. He published the results of his cataloguing in 15 definitive booklets that covered topics such as the recordings of Tanza and Stebbing, and discographies of New Zealand jazz from 1930-2000, as well those devoted to individuals such as Jim Warren, Crombie Murdoch, Rodger Fox, Ken Avery and many others.

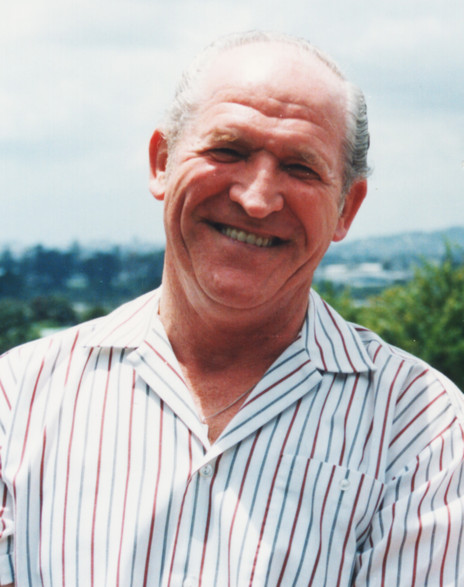

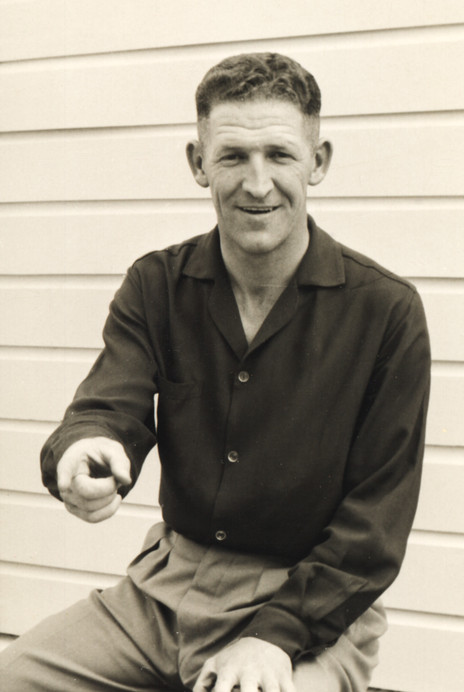

Huggard, who died in May 2017 aged 89, gave these booklets away to anybody who helped him with the research, or showed an interest in doing more. Two special editions of his “New Zealand Jazz Series” booklets are a catalogue of recordings from Tauranga’s National Jazz Festival, and The Thoughts of Musician Desmond “Spike” Donovan, a fascinating oral history interview with one of Auckland’s first jazz bassists. Donovan had a passion for local dance band history, and his memories went back to the early 1920s.

[Update: in 2018 the National Library of NZ published 15 of Huggard’s booklets and discographies online as Word files. Included among them are the Spike Donovan memoir, the “Alex MacLean” tapes of the Tauranga jazz festivals, and discographies of Tanza and Stebbing. After going to a file’s page, click on the link ending in .doc for an automatic download.]

Among the jewels in Huggard’s audio collection is his 78rpm acetate of Auckland singer Esme Stephens singing live in 1943 with the visiting US Navy band of swing star Artie Shaw (recorded from a concert broadcast). And it was Huggard’s efforts that led to the 60-second clip of Rotorua bandleader Epi Shalfoon and his Melody Boys – filmed as a promo item for cinemas in 1930 – being widely disseminated. Their rendition of the Māori pop standard ‘E Puritai Tama’ is seen as New Zealand’s first jazz recording.

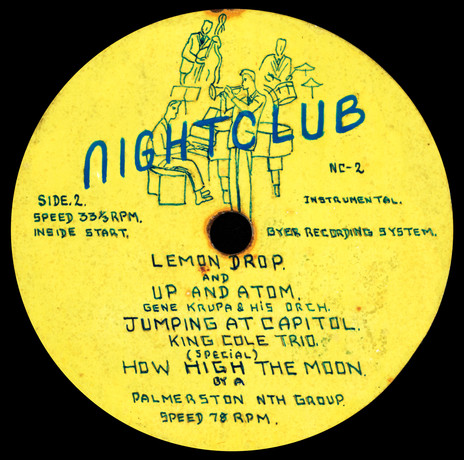

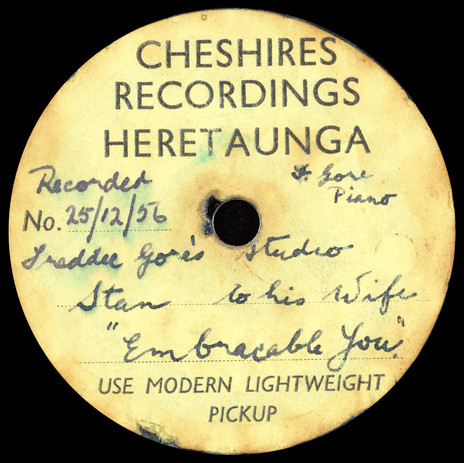

In 2009 he donated his archive, by then 9000 manila folders divided into musicians, concerts and venues, as well as audio – over 2000 items in all formats – to the Turnbull (several of the rarest items are pictured below). Named the Dennis Huggard Jazz Archive, the collection’s scope ranges from Bob Adams and Walter Smith’s pioneering Auckland jazz bands of the 1920s, includes Quincy Conserve and Nathan Haines, and carries on to what was happening at the Gables in Auckland in the 2000s. Already this large resource had been heavily used by researchers: it was the backbone of my 2010 book Blue Smoke: the Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music 1918-1964, and of Aleisha Ward’s PhD thesis “Any rags, any jazz, any boppers today?” – Jazz in New Zealand 1920-1955.

The impact of Huggard’s dogged work is only just beginning; already it has made up for decades of neglect of local popular music by New Zealand’s tertiary institutions and most of its archives. It has created a resource that enables popular music historians to describe the rich musical life that occurred before Johnny Devlin or ‘She’s a Mod’. Much of the audio he was given by the musicians themselves, pleased that someone was showing an interest in their past; he also spent long hours scouring second-hand record stores and flea markets, visiting musicians for interviews, connecting with anyone involved.

In 1995, speaking to writer Graham Reid, Huggard described all this work as “payback time for all the pleasure I’ve had.” Huggard bought his first record in 1944, aged 16. The weekly broadcasts of “Turntable” – Wellington jazz aficionado Arthur Pearce – which ran from 1937 to 1977, were essential listening. “Arthur must rank as New Zealand’s Father of Jazz,” Huggard said in 2005. “He had a great influence on the New Zealand jazz public.” While based in New Plymouth in the 1950s, Huggard emulated Pearce, presenting Rhythm Time, a weekly jazz programme on 2XP. Ten years earlier, in 1948 – aged 20 – he founded the New Plymouth Swing Club, and he wrote about jazz in fanzines and journals for years.

Back then, jazz was music for dancing as well as listening. He met his wife Rene on the dance floor of Wellington’s Empress Ballroom in the early 1950s. Without prompting he could tell you that Auckland had “38 dance halls and nightclubs operating at the same time”. Among them was the Peter Pan – at first on Rutland Street, later on upper Queen Street, evolving into Mainstreet – the Civic Wintergarden in the heart of the CBD, the Orange Hall on Newton Road, the Crystal Palace in Mt Eden, El Rey’s in Hillsborough and many others.

Huggard had an overview of the way New Zealand jazz developed from the early 1920s, not long after the genre’s first recording by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1917. (While not the first jazz band in the US, the all-white ODJB was the first to make a record.) The first overseas jazz band to visit here was the Southern Dixieland Band, which was hired from Australia for a residency at the Dixieland Cabaret in 1922. Huggard related the influence of the visit by the US “great fleet” to Auckland and Wellington in 1925: five large battleships, all with resident jazz bands that played on shore during their stint in New Zealand. He could recite a roll call of important local figures – among them Smith, Shalfoon, Julian Lee, Martin Winiata, Marion Waite, Fred Gore, Nancy Harrie, Doug Caldwell, Judy Bailey, Mike Nock – New Zealand’s own jazz Mt Rushmore. “We’ve got our own history here which is unique and exciting,” he told Reid.

While a dedicated historian, Huggard did not live in the past. He keenly followed the jazz musicians that made the Gables in Herne Bay their home, rarely missed attending the Tauranga festival, and encouraged young musicians playing in high school big bands.

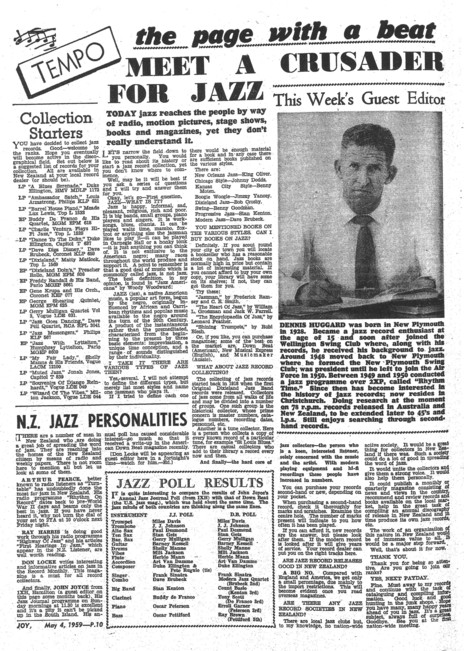

Huggard’s propensity for collecting and compiling discographical information went back to his 20s. In May 1959 he was one of Joy newspaper’s weekly “guest editors”, and said he was “doing research at the moment on 78rpm records released in Australia and New Zealand, to be extended later to 45s and LPs.” In full proselytiser mode, he compiled a list of “collection starters” that heavily featured his beloved Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong (he was appalled with jazz teachers who claimed that jazz began with bebop). He recommended a library of books for jazz beginners, encouraged the formation of clubs, and gave collecting advice. “When purchasing a second-hand record, check it thoroughly for marks and scratches. Examine the centre hole. The number of marks present will indicate to you how often it has been played.”

In his 2016 book New Zealand Jazz Life, Wellington musician and educator Norman Meehan described the Huggard archive as “an astonishingly rich repository of material which essays the development of jazz in New Zealand over the past 60 years. Dennis has been an unfailing champion of jazz in New Zealand of the music and his legacy – in the form of this record – is an important one for the music in New Zealand.”

Without Huggard’s dedication, much of New Zealand’s jazz history would have been lost. He was held in extremely high regard by Auckland musicians, not just for his dedication to recording their history, but for his generosity. He was not one of those collectors who liked to keep his discoveries to himself: like the broadcaster Jim Sutton, he wanted to support the cause of New Zealand music history. Before Huggard published his first Tanza discography in 1994 (the sixth edition came in 2009), few were still interested in New Zealand’s first independent record label.

“I never think of what it’s costing me,” Huggard said to Reid in 1995. “I give away copies of the Tanza catalogue to people I’ve interviewed or who have passed on useful information. It’s my way of giving something back and saying thank you. I love it.”

In 1959, Huggard closed his article in Joy: “Must away to my records and continue with the task of cataloguing and compiling information. Good luck and good hunting in the junk shops. Hope you have many, many happy years ahead of you in jazz. It’s a great subject, always full of surprises. Goodbye.”

--

Dennis Huggard’s New Zealand jazz discographies and catalogues have been digitised by the Alexander Turnbull Library and are available online at this link.