The dusty crypt of New Zealand pop history is papered with a bizarre collection of weekly and monthly magazines: the good, the cheap and the mostly short-lived. The weirdest and least remembered is probably Joy, a weekly paper launched on the satin coat-tails of rock and roll heartthrob Johnny Devlin by the wealthy owners of scandal sheet New Zealand Truth. It even had Bruno Lawrence on staff.

Carol Davies and Johnny Devlin on the cover of Joy , 2 March 1959

From the start the weekly sounded kind of clunky. Editions of Truth in 1958, its pages chronicling seamy divorce cases and steamy “bodgie/widgie orgies”, carried the first advertisement for Joy: “New Zealand’s newest, gayest, weekly paper”. Edited and printed in Wellington, the 24-pager made its debut a week later, featuring blonde “Joy Belles” on the newsprint cover plus headlines like “Pictures to Prove It – Rock Singer from Wanganui makes Girls Scream”.

Joy’s timing was good. The “youthquake” associated with the 50s was going off the Richter scale, as Johnny Devlin was mobbed up and down the country, his pre-ripped shirts famously torn from him in well-orchestrated stunts. Truth meanwhile, had spent much of the decade making tut-tutting noises about the rise of an American-style teenage cohort with its fashions, music and attitudes.

But sexually promiscuous “flaming youth” was proving a unit-shifting, nostril-flaring tabloid staple around the world. In 1956 Truth led the local press in mentioning Elvis Presley and his breakthrough song ‘Heartbreak Hotel’: “He rocks, rolls, bumps, throbs and thrusts with every beat of his music while frenzied teenage audiences scream and sway in hysterical imitation of this uninhibited singer.”

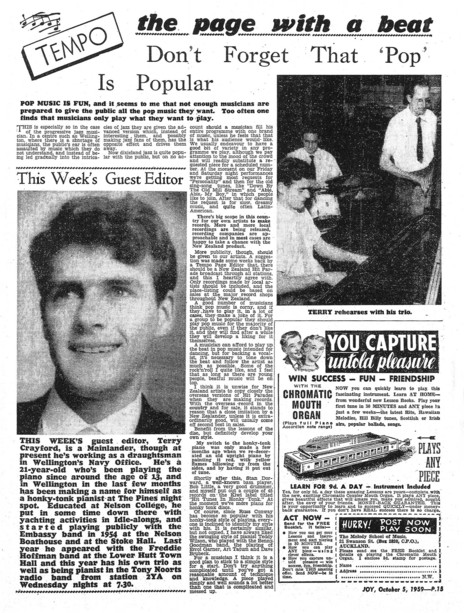

"Don't forget that pop is popular" - Terry Crayford in Joy, 5 October 1959

Stories with headlines like “Teenage Love-making at Rock’n’Roll Party”, “Love En Route in Boot of Coupe” and “The Girl Who Ruined Stratford” were becoming a weekly standby. It was not surprising, then, that Elvis regularly made the cover of Joy.

Even more prominent was Devlin, who was about to become the first local pop idol. The man who “rocked them in an orange suit” was also said to “make girls scream”. At a time when the first local strip clubs were opening their daring doors on Karangahape Road, Joy was quick to feature a “strip act” sequence of black and white photos of a topless Devlin.

By 1959, as editions of Joy hit the streets, middle of the road Kiwi performers like the Howard Morrison Quartet were forced to acknowledge up and comers like Devlin and the new sounds of rock and roll. “Every dog in the street is barking rock’n’roll,” Morrison told the paper that year after returning from Australia. “I’m not really sold on rock and roll ... whatever one feels about it, they’ve got to admit that it’s the beat that changed a generation.”

"Rock style varies" - Jimmy Rivers guest edits Joy's Tempo page, 7 September 1959

As an offshoot of the tabloid weekly Truth, Joy was feisty, ready to stick its neck out and make outrageous claims to gain reader attention. Its pop music department, entitled “Tempo - the Page with a Beat, was deliberately provocative, a mouthpiece for a succession of celebrity editors, mostly with stroppy opinions.”

Bas Tubert, star announcer on Wellington station 2ZB, was typical: “Take the ‘M’ out of music and what have you got? ‘U/sic’. Yes, me too, after listening to some of these numbers billed as top of the ‘hit parades’ throughout the world.

“It’s my opinion that we are being fed in most cases trash which is directed not at the mentality of our teenagers but the five and six year olds. Let me say that the music of rock’n’roll is good. But I want to hear more music and less rubbish.”

Some Tempo editors, such as the now legendary Max Merritt (who turned 18 in 1959), saw rock and roll as a uniting force for youth, amping up the squeaky clean-sounding Christchurch Teenagers Club he’d established with his parents.

A young Max Merritt tells his own story, Joy , 27 July 1959

“My idea of the club was to entertain the teenagers who were walking the city streets on Sunday nights without entertainment, as Christchurch is not catered for in Sunday films like Auckland and Wellington.

“My mother, with the help of teenage girls, provides the tea for the members, and everyone is well catered for, with tea, cakes, sandwiches and hot savouries. There is rock’n’roll dancing, with the Meteors on stage.”

Tempo editors took their mission seriously, even getting competitive about differences in footwork and dance routines between regions. “The Aucklanders are really fast with their movements and throw in a lot of extra moves while the South Islanders tend to have a completely slower series of moves."

Johnny Cooper, regular Tempo editor and rock’n’roll pioneer, reckoned Gisborne, his home region, boasted the nation’s true pop treasure. “There’s talent here to burn, but it’s unheard of talent because it’s an isolated spot on the map.”

Tempo guest editor Red Hewitt writes about his career with the Buccaneers, Joy, 23 May 1960

By 1959, as he wrote that, Cooper was famous for having recorded a local, mostly unplayed version of Bill Haley’s immortal ‘Rock Around The Clock’. And like Haley, he was originally a country singer (“The Maori Cowboy”) who had stumbled into rock’n’roll, never quite fitting the tight frilly shirts. He’d been happier unearthing East Coast talent with his popular “Give It a Go” shows.

He told Tempo: “The ‘Fabulous Esses’ are two boys and one girl (sister, brother and a friend), Blossom and David Marino and Luke Peach. Blossom takes lead vocal, and man! has that lass got personality! And also a voice!

“The huge audience calls for ‘Be Mine Tonight’ and gets it. The audience is quiet until Blossom moves in to the microphone, and soft and tempting she says, ‘and your kisses oh so tender’. Well, the kisses she gets from the crowd, she wouldn’t be able to cope with them all in a week. Keep it up, gang. Who knows, there may be an opening somewhere, some day.”

"Poverty Bay Talent In Action" - Johnny Cooper, Joy, 12 October 1959

Most of Joy’s Tempo editors, however, wanted a big bold headline. One daring individual, whose name has long fallen off the radar, even predicted rock’s imminent demise. “Rock and roll is past its peak here,” he wrote, “we’ll probably never see a successor to Johnny Devlin because the demand is dying off.”

Joy kept trying. Through the parent company, its editors had access to a rich trove of editorial and visual material from syndicated overseas sources paid for but never used by Truth. Apart from the pop content, its pages were packed with Hollywood tittle-tattle, busty babes, movie gossip and other celebrity material seen in racy Australian weeklies such as Pix.

But no one on the Joy staff working in the Truth newsroom was aged under 35 or had the slightest idea about the “youth market”. The risky editorial balancing act soon led to thousands of unsold copies a week. The anticipated rush of advertisements for the industries of youth – the clothing, motorbikes, radiograms, recordings, soft drinks and cosmetics – wasn’t eventuating.

By 1960, the weekly had become a uneasy blend of glamour girls (“popsies”), supplied press releases about new local pop acts, and racy syndicated features (“I Was a Dope Slave”). Truth’s owners decided it was time to hire a young person to help ensure Joy had a connection to the youth market. The job went to 18-year-old David Charles (“Bruno”) Lawrence.

Famous in later years as a drummer with bands including BLERTA and The Crocodiles, and even more celebrated as an actor, Bruno got carried away in his role as a reporter. Writing for both Joy and Truth, he got into hot water when he published a local follow-up to Joy’s sensational “I Was A Dope Slave”.

In 1960, Bruno’s expose on the local beatnik scene shone a spotlight on marijuana use by local musicians in the alleys behind Wellington venues like the Sorrento. He knew this demi-monde, playing and mingling with other musicians at this after-hours jazz club on Ghuznee Street.

At the time, cannabis, almost unknown locally and rarely grown, was demonised as a “sex drug” that made users lose their inhibitions. He tapped out on his typewriter a sequence of stories with headlines such as “Sex-Drug Plant Grown In Auckland” and “Drug Men Go to Ground”.

"The Rock's Good But Nix The Gimmix" says Wellington DJ Bas Tubert - Joy, 3 November 1958

“The big boys of New Zealand’s homegrown marijuana drug went to ground after last week’s story on their activities and the jailing of a small time vendor of reefers. But that hasn’t stopped a lot of knowalls acting as if they are on the fringe of the racket themselves, talking big in coffee bars…”

Roger Booth’s 1999 biography Bruno relates how his reporting career for Joy and Truth came to a sticky end after a visit to the newsroom by plainclothes detectives, demanding to know his sources. Bruno felt terrible: he was trapped. He did know some of the people but had no idea if they were “involved”. He ran for cover, and left journalism forever.

As Lawrence departed, Joy folded. The piles of newsprint copies stored in the air conditioned vaults at National Library have an amateurish look, with their weak cover lines, scrappy content and variable use of spot colour. But the weekly’s owners were onto something: the 1960s youthquake was rumbling to life; they had just got in a bit too early.