The Quincy Conserve

In an international context, The Quincy Conserve was hardly unique, and it doesn’t take a special pair of ears to pick up the similarities with slick, jazz-influenced, horn-led American groups like Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago Transit Authority.

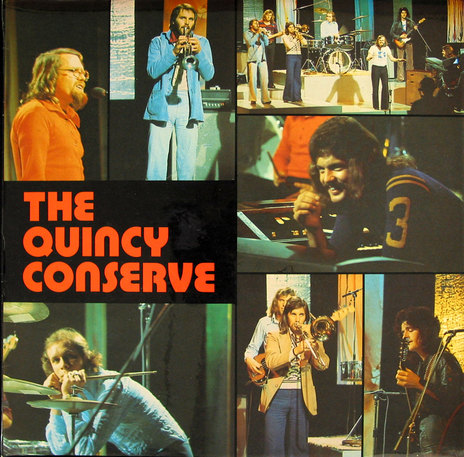

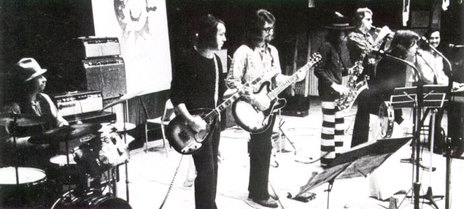

Quincy Conserve on the Brian Edwards-hosted television show Edwards On Saturday, March 1976.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

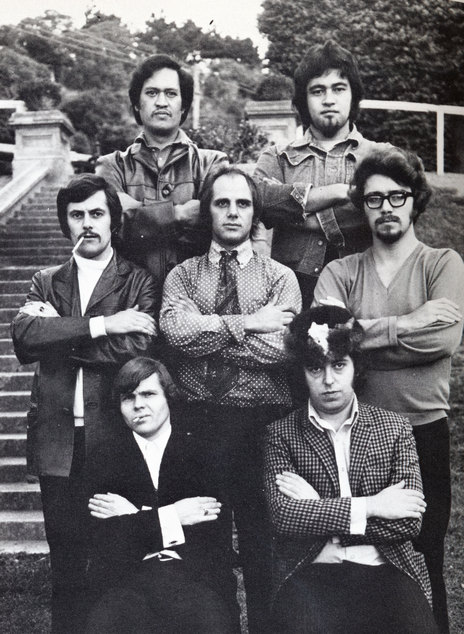

Quincy Conserve in 1970: Left to right, top to bottom: Rufus Rehu, Denys Mason, Johnny McCormick, Bruno Lawrence, Kevin Furey, Malcolm Hayman, Dave Orams

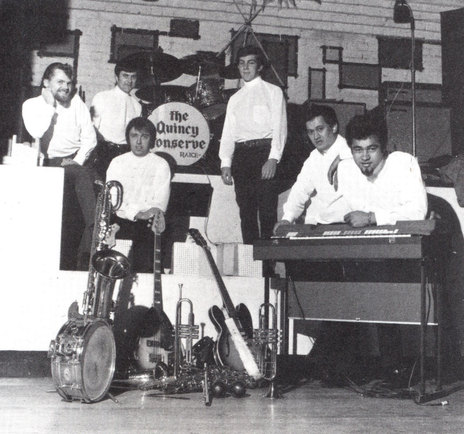

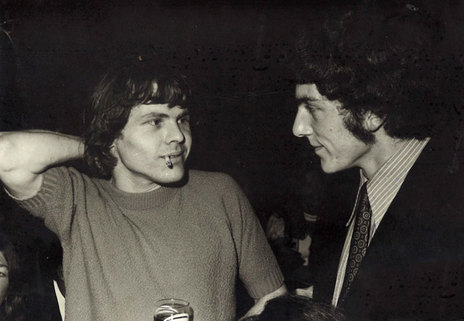

Quincy Conserve in the Downtown Club

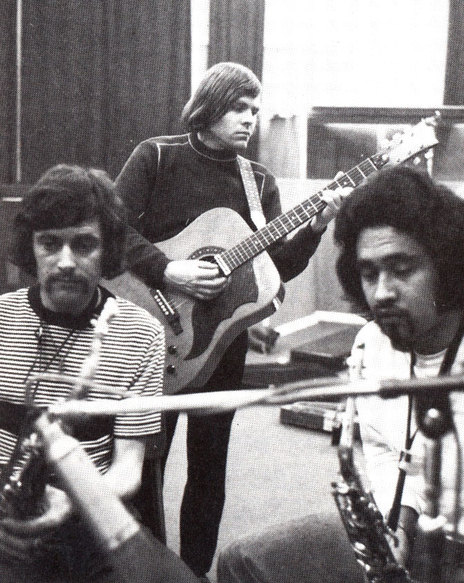

Quincy Conserve having a band conference after a take. HMV studio, Wakefield Street, Wellington, 1971.

Quincy Conserve in 1973. Left to right at rear: Billy Brown, Peter Blake, Rodger Fox, Geoff Culverwell, Murray Loveridge. Front: Malcolm Hayman, Paul Clayton

Photo credit:

Murray Loveridge collection

Quincy Conserve in 1971: Barry Brown-Sharpe, Dave Orams, Malcolm Hayman, Denys Mason (rear), Richard James Burgess (front), Rufus Rehu and John McCormick

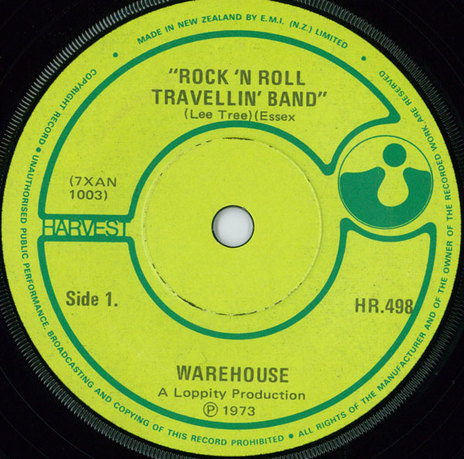

The 1973 single from "Warehouse" - actually Quincy Conserve under a fake name. The B side, 'Brurp', was recorded by BLERTA.

Quincy Conserve, 1969: Malcolm Hayman, Rufus Rehu, Ria Kerekere, Johnny McCormick, Denys Mason and Dave Orams with Raice McLeod in front.

Photo credit:

Photo by Murray Menzies

The final Quincy Conserve album, released in 1975 for Ode Records, is regarded now as a classic but has long been out of print on CD or vinyl

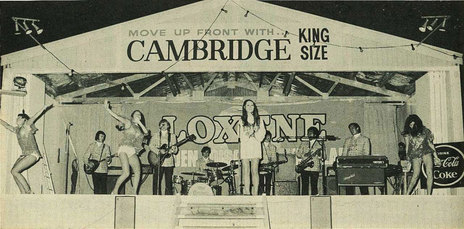

Quincy Conserve backing Allison Durbin at Gisborne's Beach Carnival, January 1969

Photo credit:

Gisborne Photo News

Quincy Conserve on the Brian Edwards-hosted television show Edwards On Saturday, March 1976.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

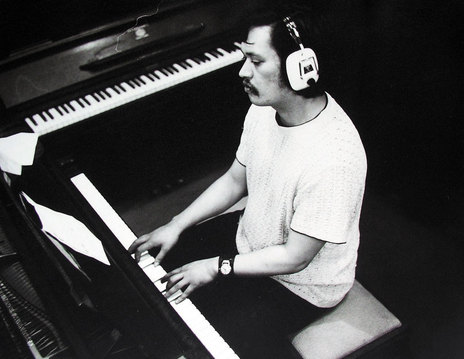

Quincy Conserve recording at HMV

Quincy Conserve in Gisborne, January 1969. At rear: John McCormick, Malcolm Hayman, Denys Mason. Front: Rufus Rehu, Raice McLeod, David Orams.

Photo credit:

Gisborne Photo News

Malcolm Hayman at The Spectrum Bar, Wellington

Malcolm Hayman and Raice McLeod

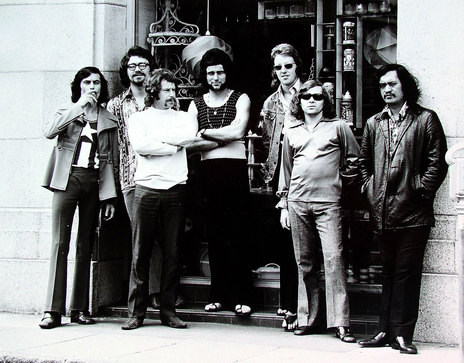

Quincy Conserve in Wellington, 1971: Fritz Stigter, Mike Conway, Barry Brown-Sharpe, Malcolm Hayman, Rufus Rehu, Johnny McCormick and Kevin Furey

Photo credit:

Grant Gillanders collection

Quincy Conserve 1971

Photo credit:

Grant Gillanders collection

The 1973 EMI album Tasteful was a more rock orientated album than its predecessors. Designed by Ian Munro and Terence Eady.

Quincy Conserve at Wellington's Downtown Club, circa 1969

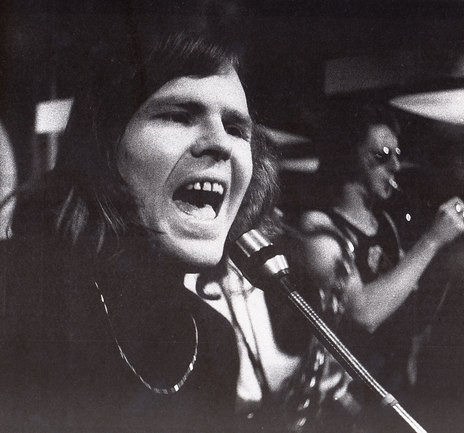

Quincy Conserve performing on TV's Grunt Machine. Malcolm Hayman on vocals, Peter Blake on keyboards.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

Quincy Conserve on the Brian Edwards-hosted television show Edwards On Saturday, March 1976.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

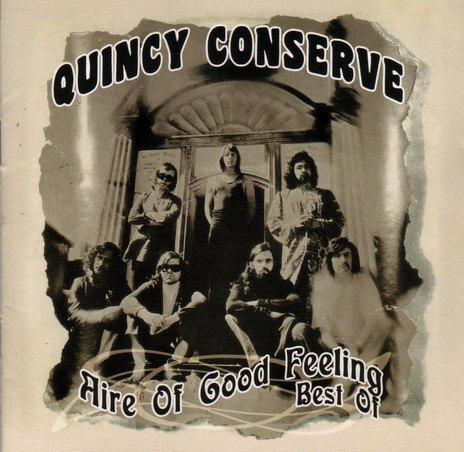

The sleeve for the group's second album recorded between August and December 1971 at HMV Studios in Wellington. The title and '1967-1971' on the cover referred to the fact that the band had broken up by the time the album was released. Produced by Peter Dawkins, the album featured the bands signature tune Aire Of Good Feeling which gained extensive coverage when used to promote TV2 in 2008.

Quincy Conserve north of Wellington, 1971

Peter Dawkins with Quincy Conserve at HMV studio in early 1971. From left: Denys Mason, John McCormick, Rufus Rehu, Barry Brown-Sharpe, Dave Orams, Richard James Burgess, and Malcolm Hayman. Seated are Peter Dawkins and engineer Peter Hitchcock. Visible behind Rehu is the top unit of the 4-track Ampex tape recorder.

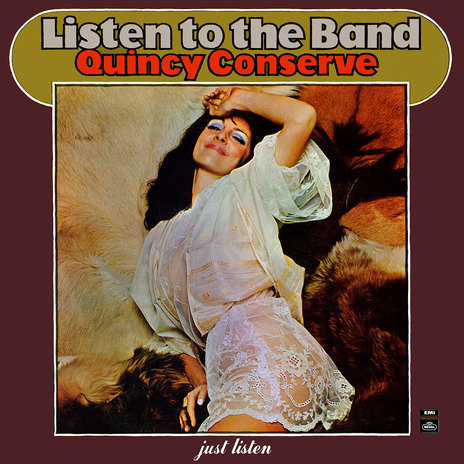

The cover art for the 1970 Peter Dawkins - produced debut album of Malcolm Hayman's Wellington band. The line up for this album included Bruno Lawrence, who penned the band's breakthrough hit Ride The Rain.

A rare colour shot of The Quincy Conserve c.1969: Denys Mason, Malcolm Hayman, Raice McLeod, Rufus Rehu, Dave Orams and Johnny McCormick

Photo credit:

Photo by Sal Criscillo. Ken Cooper collection

The 2008 Quincy Conserve compilation, put together for EMI by Grant Gillanders, used all the original tape masters

Johnny McCormick with Quincy Conserve at The Downtown Club, circa 1969

Rufus Rehu recording at HMV Studios, Wellington, 1971

Quincy Conserve in 1972: Mike Conway, Dave Orams, Kevin Furey, Johnny McCormick, Barry Brown-Sharpe, Malcolm Hayman, Rufus Rehu.

John McCormick

Quincy Conserve on the Brian Edwards-hosted television show Edwards On Saturday, March 1976.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

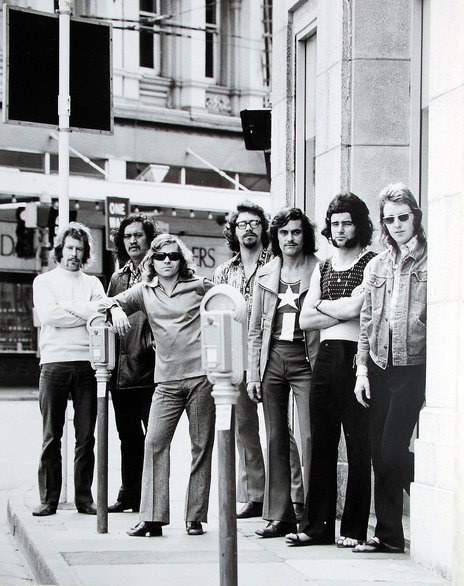

Quincy Conserve on the corner of Willis Street and Lambton Quay, Wellington, early 1970s. Left to right: Mike Conway, Rufus Rehu, Malcolm Hayman, Kevin Furey, Johnny McCormick, Fritz Stigter, Barry Browne-Sharpe.

The Brothers Johnson in New Zealand circa 1973, backed by The Quincy Conserve at Wellington's Downtown Club

Photo credit:

Photo by Bob Leask

Quincy Conserve in 1968: Denys Mason, John McCormick, Rufus Rehu, Malcolm Hayman, Raice McLeod, Kevin Furey and Dave Orams.

Quincy Conserve on Edwards On Saturday, March 1976.

Photo credit:

Peter Blake collection

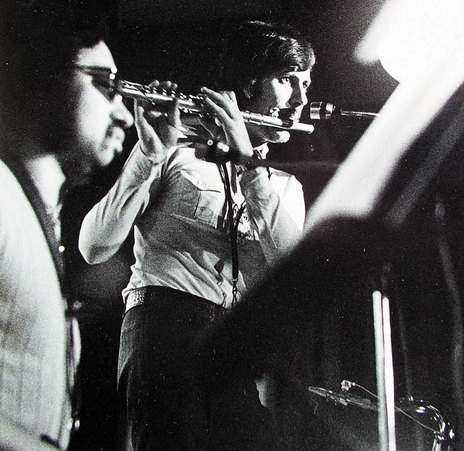

Denys Mason and John McCormick recording with The Quincy Conserve in HMV, 1971

Labels:

HMV

Regal

Trivia:

Johnny McCormick and Dennis Mason amplified their saxophones by using old hearing aids as microphones.

The Quincy Conserve was named by Dalvanius Prime.

Members:

Malcolm Hayman - vocals, guitar, arrangements

Dave Orams - bass

Johnny McCormick - saxophone

Kevin Furey - guitar

Barry Brown-Sharpe - trumpet

Tom Swainson - drums

Graeme Thompson - bass

Geoff Culverwell - trumpet

Murray Loveridge - bass

Bill Brown - drums

Paul Clayton - guitar

Bryan Beauchamp - drums

Earl Anderson - drums

Mike Conway - drums

Peter Cross - trumpet

Harry Leki - guitar

Fritz Stigter - bass