AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

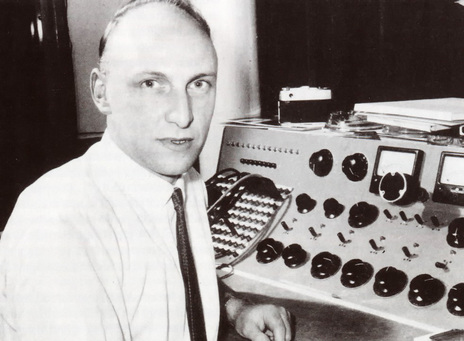

Frank Douglas

From the chart toppers of Shane and Allison Durbin to the underground rock of Ticket and Tamburlaine, the soft-spoken soundman left his stamp on some of the most significant records made in New Zealand.

Frank Douglas moved from Waitara to Wellington in the early 1950s to serve an apprenticeship as a radio repairman with the Radio Corporation of New Zealand. After completing the five-year course, he spent a year servicing equipment, then shifted to a job at the corporation’s recording studio, where he trained as a recording engineer under the supervision of Terry Patterson. The studio had been established in 1949 along with the country’s first independent record label, Tanza.

Though Tanza’s mission was encapsulated in its name – To Assist New Zealand Artists – and had produced a number of successful records including Pixie Williams’s iconic ‘Blue Smoke’ (written by Ruru Karaitiana), Douglas’s work for the Tanza studio mostly involved radio commercials, which he cut directly to acetate discs. Any mistake and the recording had to be started again. Frank recalled some recordings being made 50 times before a take was deemed acceptable.

When Patterson left Tanza in 1960 to set up a new studio, Lotus, Frank went with him. At Lotus, Frank began working with magnetic tape. Originally owned by Tasman Vaccine Laboratories, Lotus was bought in 1964 by His Master’s Voice, the local subsidiary of the British multinational recording company EMI.

EMI had branches scattered throughout the Commonwealth. The company had been manufacturing records in New Zealand under the HMV brand since 1949, and as well as promoting these predominantly English recordings, the company set aside part of its budget for local productions.

In New Zealand, HMV’s local productions began in the early 1950s with original country songs from Les Wilson, piano medleys performed by John Parkin, and the country and rock and roll recordings of Johnny Cooper. Without a studio of their own, they outsourced recording to Alan Dunnage’s Sonic studios in Island Bay.

But once they had taken over Lotus – rechristening the Wakefield Street studio HMV – local production began in earnest. The Beatles had just gone ballistic, the British invasion was underway, and longhaired beat groups were popping up all over the world. One of the first local beat bands signed to HMV were The Librettos.

Listen to the Wellington-based quartet’s 1965 album Let’s Go With The Librettos and you’ll hear a raw rhythm and blues sound, closer to The Rolling Stones than The Beatles. Their original ‘I’m A Dog’ snaps and snarls as convincingly as any garage R&B band of the period, anywhere.

Rod Stone, guitarist for The Librettos, says the credit rests with Douglas. “Frank was the person who made all The Librettos’ records what they were. He was the unofficial producer who helped us get the sounds we were dreaming of.”

Not all the studio’s work was for HMV’s own label. John Hore came in to record his country songs for Joe Brown Records. Peter Posa, Dinah Lee, Maria Dallas and, briefly, Max Merritt’s Meteors made theirs for Viking. Douglas worked on all of them. Again, the explosive power of a record like Dinah Lee’s ‘Do The Bluebeat’ (with the Meteors providing backup) has a lot to do with Douglas’s ability to capture a performance, in all its raw energy. Yet equally impressive is the clean bright production of Peter Posa’s guitar instrumental ‘White Rabbit’.

Until the mid-1960s all HMV’s recording was in mono, with a maximum of eight microphones that were balanced by the engineer at a simple console.

Pop was starting to make its presence felt on television as well. Weekly pop show Let’s Go was fronted by NZBC disc jockey Pete Sinclair, and featured local groups and singers, performing to pre-recorded backing tracks. These were recorded at HMV a few days before each programme went to air. Frank would record eight or 10 backing tracks for each show, which usually constituted a day or day and a half’s work.

Until the mid-1960s all HMV’s recording was in mono, with a maximum of eight microphones that were balanced by the engineer at a simple console as the music was going to tape.

Working closely with his fellow engineers, who at this time included Brian Pitts and Peter Hitchcock, Frank developed techniques for the placement of microphones and screens around the instruments and amplifiers. “What we used to aim for was an overall sound – not individual sounds – a pleasant group backing sound,” he told me in 1992.

“We’d try and balance the thing within itself in the studio half the time. You’d stand in front of the instrument or amplifier and listen, and if it sounded all right you place microphones in front and it usually came out much the same in the control room.”

When a more particular sound was required – for instance, the echo effect that characterised rock and roll records of the period – it was up to the engineers to create it.

Using a construction manual and their own ingenuity, Frank and Chris Parkinson built their own echo plate, suspending a steel sheet in a tubular steel frame with a loudspeaker attached and a crystal pickup on top to pick up the vibrations. It worked just like a bought one.

Using a construction manual and their own ingenuity, Frank and Chris Parkinson built their own echo plate.

This camaraderie and do-it-yourself approach was typical of the studio in this period. As Frank recalled: “If one person wasn’t there to do something, someone else could do it. We were all fairly versatile so we could swap over and do each other’s job if we had to. It made life fairly easy really, because you could always rely on someone helping you out.”

By the mid-1960s the studio had acquired its first stereo tape recorders. Even then, the technology was primitive by today’s standards. When a recording required overdubbing – for instance, a vocal added to instrumental backing track, harmonies added to a lead vocal, or an instrumental solo – two tape recorders would be used. “We used to dub from one machine to the other and each time we dubbed we would add an extra section in, either a vocal or an instrument, or whatever. Some of the early recordings had six or eight dubs on them, from tape to tape to tape to tape to tape.”

By the time the final master recording was completed, some of the instruments had been dubbed from tape to tape half a dozen times. Surprisingly, little quality was lost in this process, any sacrifices in fidelity made up for by the vibrancy of the production as a whole.

Amongst the engineer’s tasks was the cutting of master discs for local pressings of overseas records. This exposed Douglas and his fellow engineers to all the latest sounds, which they would puzzle over, discuss, and try to figure out how they had been achieved. No matter that these records were generally made on a much bigger budget than New Zealand recordings; they set an industry standard that Douglas and his colleagues strove to match.

Initially it was the engineers who effectively “produced” the recordings, making the critical decisions about sound, balance and performance, with occasional input from a manager, promoter or arranger. But by 1967, HMV had hired Howard Gable, the first in a series of house producers, who would work closely with the engineers.

As the beat boom blurred into the psychedelic era, the demand grew for more outlandish sounds and effects.

As the beat boom blurred into the psychedelic era, the demand grew for more outlandish sounds and effects. “Flanging” was the name – coined by John Lennon – for an effect first heard on British-made records such as The Beatles’ ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and The Small Faces’ ‘Itchycoo Park’. It was particularly striking when used on drums. The effect is created when two identical sound signals are mixed together, one delayed by a miniscule and gradually changing period.

The best local example can be found in ‘Spinning Spinning Spinning’, a 1968 hit for The Simple Image, where it’s featured in the middle section and again at the outro, creating the impression that the entire recording is spinning tornado-like, somewhere above the listener’s head.

Again, the effect required a pair of tape recorders, with Douglas manually slowing down the revolving reel on one of the machines, while fellow engineer Peter Hitchcock manned the recording console. Douglas recalled it taking an afternoon and many attempts to perfect.

Another popular sound in the psychedelic era was the Elizabethan chime of a harpsichord. The fact that HMV didn’t have one was no obstacle. The part was played on the studio piano to a tape running at half speed. When played back at the correct speed the piano sounded convincingly like a harpsichord.

Working with a succession of producers including Peter Dawkins, Nick Karavias and Alan Galbraith, Douglas continued to engineer a huge variety of types of music: psychedelic pop with The Avengers and The Fourmyula, novelty skiffle with Hogsnort Rupert, funk and soul with The Quincy Conserve and The Yandall Sisters.

In late 1971 psychedelic rockers Ticket turned up with their huge amplifiers and haystack hairstyles. They had come direct from Christchurch where they had perfected their tight and heavy sound through long nightly appearances at Aubrey’s nightclub.

Ticket didn’t have a producer, but Douglas’s quiet efficiency enabled them to record the entire Awake album in just three brief sessions. The album is recognised today as a psych-rock classic.

In the early 1970s Michael Grafton-Green arrived from London, direct from EMI’s studio at Abbey Road where he had worked on Beatles records using the most up-to-date equipment, and it was at his insistence that the studio’s ancient 4-track equipment was replaced with an 8-track recorder and Neve console, which by the mid-1970s would be upgraded to 16-track. He and Douglas worked together on increasingly ambitious recordings, including hits for BLERTA, Mark Williams and Rockinghorse.

In 1976 HMV – now formally renamed EMI, after its parent company – moved its studios to a new purpose-built facility in Lower Hutt, adjacent to its pressing plant. The new studio was much larger than the Wakefield Street one, and was promoted as the best in the country.

The decision to move had been made at EMI’s head office in Britain, reasoning that it would be more efficient to have the company’s studios and manufacturing plant in the same facility. But what looked good on paper was less successful in practice. Douglas estimated up to 80 percent of the business was lost in the shift. Meanwhile the rise of commercial radio and their imported playlists was making it harder for local recordings to get airtime, which contributed to a downturn in recording.

Frank also wondered whether the bigger recording space – while ideal for orchestras – was less suited to smaller groups. “You had to separate everyone to isolate instruments and it led to a feeling of estrangement between players,” he told me. “Whereas at the old studio they were all crammed in together and they had that feeling of being one.”

When EMI closed its studio in 1987, Frank set up his own small facility, South Pacific Recording, at his Eastbourne home. As ever, his work was diverse, from school orchestras to Dame Malvina Major.

Around the turn of the millennium, Frank – by now in his late 60s – returned to Waitara, where he set up a further home studio and continued to record local acts as well as a regular country music programme for Access Radio Taranaki. It was only in 2014, after 60-odd years in the business and with his health in decline, that this recording pioneer packed up his mics and coiled his cables for the last time. Frank Douglas passed away on 19 February 2015.

HMV

EMI

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air