Their song ‘Under the Sun’ was their best, most popular hit: a rare blend of protest ballad, sacred song and languid Māori strum. It haunted me when I heard it as a pimply kid – and still does. Half a century on, it remains a strangely touching plea for unity and nationhood (albeit with a sting in its tail).

The Kini Quartet occupies a quiet corner of that vivid 1960s’ convergence of Māori and talent

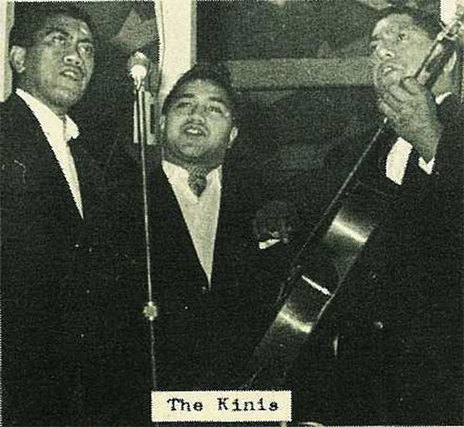

The Kini Quartet (initially Martin Kini, Joe Williams and Esther and Barney Taihuka) occupies a quiet corner of that vivid convergence of Māori and talent in the 1960s we recall as the “Showband era”. Groups like the Māori Hi-Five, Quin Tikis and the Māori Volcanics would hit the high spots on the Pacific entertainment circuit, often going on to Europe and the US.

Significantly, Martin Kini was the brother of Thomas Kini, a member of the foundational Hi Quins showband (sister group to the Hi-Fives), and much later a noted Chicago-based musician (New Zealand Trading Company). Martin, however never strayed much past Auckland, his band going on to record eight singles for Zodiac, RCA and EMI between 1962 and 1974 and a solitary long player.

The Kini Quartet started out in 1958 as a larger group of eight men and one woman, singing and performing at regional talent quests. They would rehearse in various members’ living rooms, and knew they were sounding good when neighbours, rather than complain about the noise, would switch off their radios and open their windows to listen. Gradually the line-up was winnowed down to the foursome that performed on their initial records. All four would sing, normally using just Barney Taihuka’s guitar – a Levin acoustic model – for accompaniment.

Interviewed in the 1980s for Gisborne’s Tūranga FM, Joe Williams recalled: “It didn’t need any amplification. You could play it in the Town Hall in Gisborne and hear it down in Roebuck Road. A great guitar. We had the guitar facing the back of the hall, and the voices projecting forward.” It was Joe’s job to tune the instrument, something he had a natural ear for, even in a noisy hall.

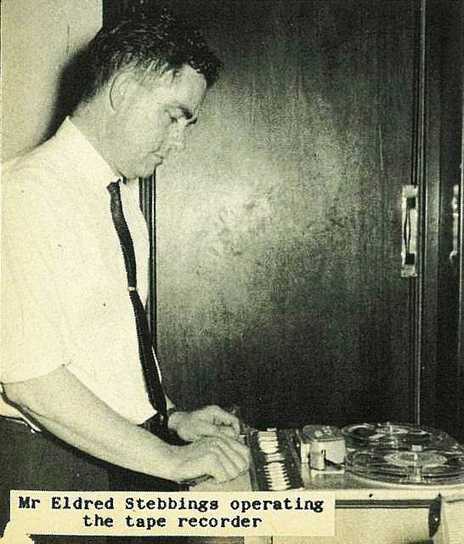

After winning a marathon six-week competition at the Waikanae Beach soundshell in Gisborne, for which they took home one hundred pounds and a tin of biscuits, they went looking for a recording deal. Eldred Stebbing of Auckland-based Zodiac Records expressed an interest but insisted they come up with some original material.

As it happened, they had become friendly with Gisborne songwriter Margaret “Tiny” Raggett, who contributed two songs for their first single. One was a comic novelty ‘Hard Times Are Coming’; the other was ‘Te Kotahitanga’, the te reo version of the song that would become their biggest hit as ‘Under the Sun’. It was recorded in Gisborne with Peter Posa adding his distinctive electric guitar.

Then came ‘Jenny & Johnny’, followed by a double A-side of covers of Brian Hyland's ‘Sealed With A Kiss’ and The Flamingos’ hit ‘I Only Have Eyes For You’. The Jock Nisbet Group provided backing. The singles sold well to a loyal and growing fanbase but their success was dwarfed by ‘Under The Sun’, which followed in 1963.

It was not the first Māori hit to tackle the thorny issue of racism. In 1960, the Howard Morrison Quartet had released 'My Old Man’s An All Black', a parody of the Lonnie Donegan hit 'My Old Man's A Dustman'. It featured humorous, mostly gentle digs at the outrageous decision by New Zealand rugby officials to exclude Māori players from a 1960 South African tour.

'My Old Man’s An All Black' was recorded live at the Pukekohe Town Hall, where the doors were famously locked to prevent the audience leaving during recording. By 1am, the restless populace was finally allowed to go home, the producer happy with the cut, which reportedly sold a massive 60,000 copies.

Recording the song just above the northern border of the Waikato, a region sometimes called the “Deep North” was an intriguing one. In 1961, a weekly newspaper lifted the lid on Pukekohe’s shocking racism, revealing that only two of the town’s six barbers would cut non-European hair. Nor were Māori allowed to sit upstairs at the local picture theatre.

Most New Zealanders had no idea of the ugly streak of racism simmering below the polite veneer of the postwar years. In 1950, for example, seven members of a Māori softball team from the King Country were refused accommodation in a downtown Auckland hotel after they had booked in and paid deposits. The manager told a gobsmacked journalist that the presence of Māori guests was “bad for morale”.

As Bob Dylan famously sang, “the times were a’ changing”. Māori were busy migrating to the towns and cities. In 1945, three quarters of Māori lived in the country; by the time 'Under the Sun' was released in 1963, only about one-third remained on the rural marae. The exodus would continue. But those heading for the bright lights faced major social and economic challenges.

Māori were discouraged from speaking their own language and urged to become British New Zealanders.

The story is not pretty. In schools and workplaces, Māori were discouraged from speaking their own language and urged to become British New Zealanders. A government report from the time called on Kiwis to become “assimilated” as one people, Māori presumably setting aside their separate cultural identity.

Margaret Raggett (1931-1999) worked to weave many of these gnarly themes into ‘Under the Sun’, the best of the songs she wrote for the Quartet. Fascinatingly, she also penned two of Peter Posa’s lesser-known hits, 'Grasshopper' and 'Hitch Hiker'.

'Under the Sun' starts with a solemn spoken introduction in a deep Sunday morning baritone: “It has been written in the book for men/ that all men are equal under the sun.”

The Kinis croon Raggett’s lyrics, blending gentle irony and pathos: “In the land of the free in our own country/ Where our babies are taught as one/ Where they learn to be men, lift up their faces and then/ Walk hand in hand into the sun.”

The second verse is a matchless slice of Kiwiana: “And God, he smiles on these two little isles/ Nestled in peace and plenty under the sun/ His rays shine down on each little town/ Where all are one, under the Sun.”

The song helped put the Quartet on the map. At the end of that year, following the assassination of US President John Kennedy, the song became something of a plea for unity. The Gisborne concert by the Waihirere Concert Party for visiting Governor-General Sir Bernard Fergusson climaxed with ‘Under the Sun’. They also performed for the Queen at Waitangi.

The single sold in excess of 30,000 copies and remained in the Zodiac catalogue for a decade.

With a nationally successful single, the Kini Quartet began touring extensively outside their hometown. Joe Williams remembers: “We commuted from Gisborne to Wellington and Auckland. Our manager Basil Lawrence had a love for Jaguar motor cars. We just travelled in style, sat back and he did the driving. Wellington here we come! Auckland here we come!”

Their versatility meant they could play anywhere from cabarets to town halls, open air stages to the Miss New Zealand Show, which they performed at three years in a row. According to Williams, their favourite venue was the Bowl of Brooklands in New Plymouth’s Pukekura Park, these days the site of the annual Womad festival. On one occasion they shared a bill there with Kiri Te Kanawa, by this time a huge star. But Williams remembered her from when they were both growing up in Gisborne.

“In my younger days when I would walk home from school, she would stand by the fence with her long hair and poke her tongue out at me. And I said to myself, ‘One day I’ll pull her hair’, or something like that. My mother caught me [saying that] and said, ‘I’ll tell your grandmother on you’. Years later I said to Kiri, ‘Do you remember those days?’ and she said yes. They were good old days, for her and for us. Our young days. Our Gisborne days. Our whanau.”

‘UNDER THE SUN’ SOLD IN EXCESS OF 30,000 COPIES AND REMAINED IN THE ZODIAC CATALOGUE FOR A DECADE

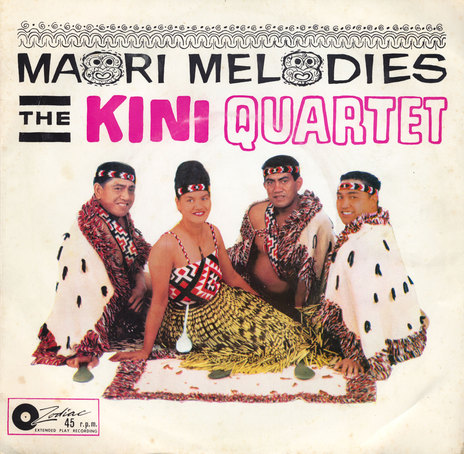

Eventually, covering long distances began to wear on the group so they relocated to Auckland. When they weren’t on the road they would perform at The Māori Community Centre in Fanshawe Street. In 1966 they moved even further afield, spending two years in Australia. During their time in Sydney their floor show became increasingly sophisticated, with multiple changes of costume including a traditional Māori segment in which Esther performed a double and then triple poi routine while the men brandished taiaha.

They shared stages with the Platters, the Ink Spots and the Korean Kittens, and crossed paths with a New Zealand legend, Prince Tui Teka. Williams recalls running into the larger-than-life singer outside a Sydney nightclub. He was resplendent in a three-piece suit, complete with bowtie – and jandals. “I said – looking at his feet – ‘Hey man…’ He said, ‘I know, I know. But I feel good’.’’

Several more singles followed plus an EP, Maori Melodies, in 1965. The Quartet then parted ways with Zodiac, moving to RCA in 1967 for one single, ‘Vaya Con Dios’, backed by The Dave Donovan Quartet.

‘Under The Sun’ was released in Australia and proved particularly popular in Adelaide where it remained in the local charts for several months. The group performed the song on television there, dressed in traditional Māori costume. But ultimately homesickness brought them back to New Zealand.

Martin Kini left the group in the late 1960s for a solo career and was replaced by Richard Bell. The band kept the name, returning to Zodiac in 1969 with the Murray Sutherland-composed single ‘Mr. Jones’. In 1970, Esther Taihuka left to return to Gisborne, and John Hemopo joined.

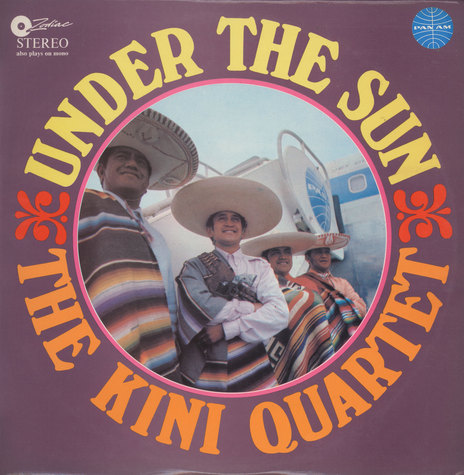

The astute Phil Warren then took over the Kini’s management, masterminding their 1970 debut album. Produced by Jimmie Sloggett and named Under The Sun, it featured re-recorded versions of many of the earlier singles. A fresh hit, ‘The Ballad of Pancho Lopez’, sold well thanks to the Quartet’s 1969 and 1970 residencies on the NZBC Studio One show.

The final single (now as the Kini Trio) was the topical ‘Don't Leave Us Now (The Ballad Of Milan Brych)’, issued by EMI in 1974, after which the group quietly faded.

Martin Kini died in 2008, the last of the Quartet to pass away. But the 20,000 plus hits on YouTube and the warm comments surrounding the clip confirm that ‘Under the Sun’ and The Kini Quartet left an indelible mark on the New Zealand songbook.