By that stage Morrison already had almost 40 years in music, starting when he replaced Kahu Pineaha in the Clive Trio in Hawke's Bay in the early 1950s. But it’s his work with the Howard Morrison Quartet that made him a household name in the late 1950s.

Early life

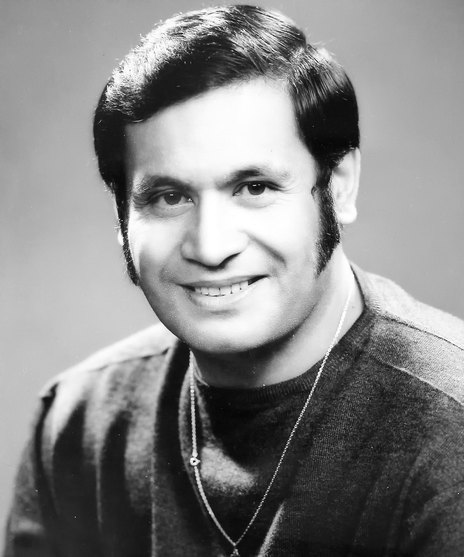

Morrison was born in Rotorua on August 18, 1935, the second of seven children of Gertrude Harete “Kahu” Morrison and Temuera Leslie Morrison. He is of Te Arawa, Scottish, Tainui, and Irish descent.

There was another son, who died in infancy, and four girls.

When Morrison was 10 his father, a Māori Affairs community officer, was posted to the remote Urewera settlement of Ruatāhuna.

Apart from having to learn te reo Māori to fit in to the Tūhoe community, Morrison remembered listening on the battery-operated radio on Wednesday nights to Selwyn Toogood playing the Lifebuoy Hit Parade, learning the songs by heart.

In his autobiography, Morrison said it gave him an appreciation for the sort of middle of the road popular songs the majority of people wanted to listen to.

A scholarship to Te Aute College took him to Hawke's Bay for three years, returning to Rotorua for his last year of school.

In early 1954 he moved back to Hastings to work, first as a storeman at an apple packing shed, then at the Whakatū freezing works.

It was during that year that he started to sing in public in a disciplined way. The Whatarau family got him to join the church choir, then the Awapuni Concert Party, and then sisters Isobel and Virginia Whatarau asked him to replace Pineaha in their trio.

Morrison remembered the Awapuni Concert Party as the first cultural group to mix contemporary music with traditional songs.

The first half would be poi and piupiu, and for the second half the backing guitarists would come out and do ‘Guitar Boogie’, after which the Clive Trio would perform, the sisters in ball gowns, Morrison in suit and bow tie.

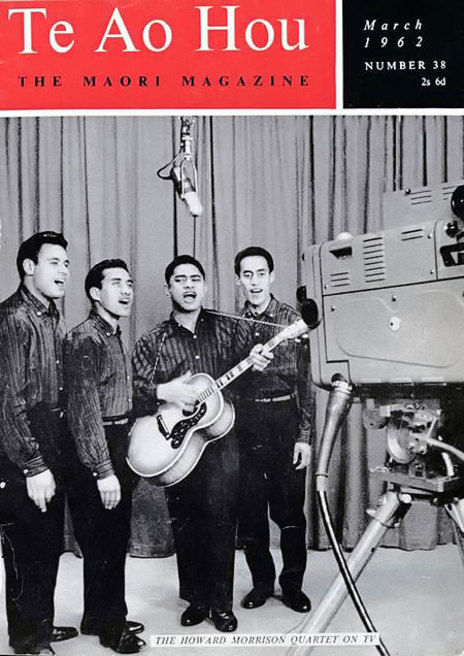

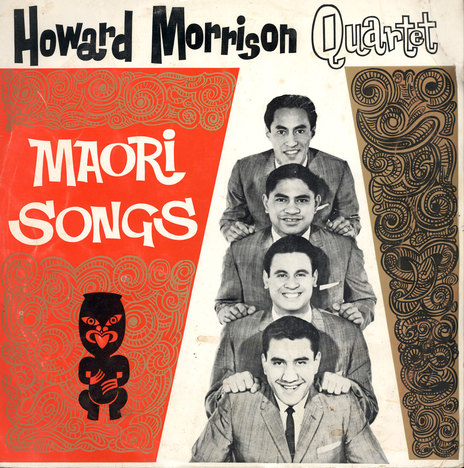

Howard Morrison Quartet

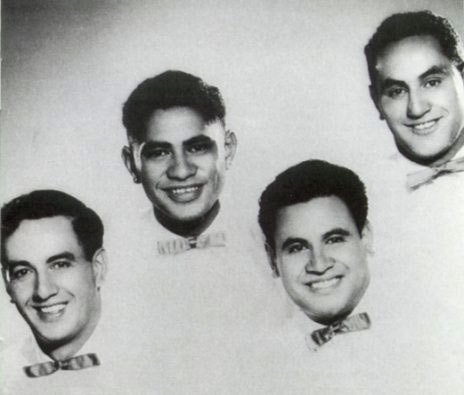

The death of his father at the end of 1954 brought Morrison back to Rotorua, where he started singing with his older brother Laurie at their Waikite Rugby Club as the Ōhinemutu Quartet.

In 1955 Morrison’s group won a talent competition at the Rotorua soundshell with a medley of ‘Rock Around The Clock’, ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and ‘Shake, Rattle And Roll’.

He recruited Gerry Merito after hearing him play guitar at a family gathering, and others who participated at various times included cousins John and Terry Morrison, Wi Wharekura, Tai Eru, Gary Rangiihu and Chubby Hamiora.

In 1955 Morrison’s group won a talent competition at the Rotorua soundshell with a medley of ‘Rock Around The Clock’, ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ and ‘Shake, Rattle And Roll’. That was enough to convince him to give up his job on brother Laurie’s surveying chain and become a meter reader with the Tourist Department.

Going full time

The switch to becoming full time professional musicians would take another five years, in part because there was no such career in New Zealand in the 1950s, and in part because some of the other members were developing the careers that eventually led to them leaving the group when it took off.

Band members were also starting families – Morrison married Kuia in 1957 and their first child Donna was born the following year.

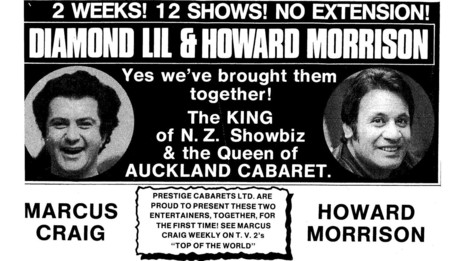

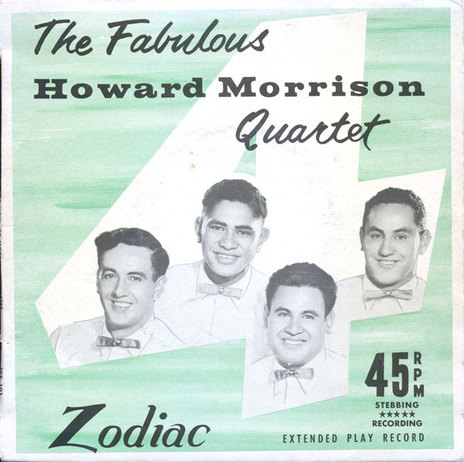

Promoter Benny Levin first heard Morrison and his quartet at the Ritz Hall in Rotorua in Christmas 1956. He started bringing them up to Auckland for one-off shows at venues including the Town Hall, and introduced them to Eldred Stebbing of Zodiac Records.

It was Stebbing who suggested the band be called the Howard Morrison Quartet, recognising that even if the band broke up, Morrison could continue to be a performer.

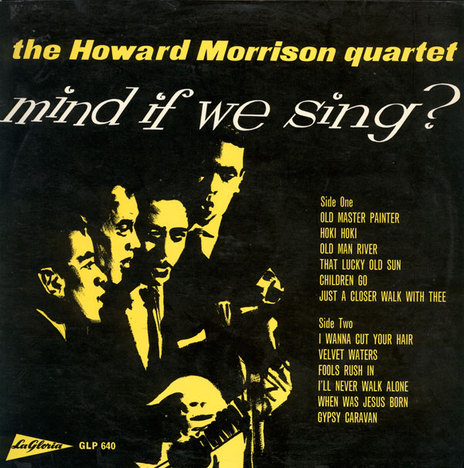

Their first recordings were covers, but the one that took off was ‘Hoki Mai’ done to the tune of ‘Goldmine In The Sky’ – a song from Morrison’s Awapuni Concert Party days.

When Benny Levin decided the time was right for a national tour, Morrison put the hard word on the band. Laurie Morrison and Tai Eru dropped out, and Howard went on the road with Gerry Merito, Wi Wharekura and Stebbing protégé Eddie Howell.

That first tour didn’t make money, but a live recording of Merito’s song ‘Battle of the Waikato’, a parody of Lonnie Donegan’s ‘Battle of New Orleans’, became a huge hit.

Harry M. Miller

Back home in Rotorua in early 1960, Morrison walked into a store in time to see a salesman demonstrating an electric cooker. The salesman recognised him and announced to the crowd he would be the Quartet’s manager. That was Morrison’s introduction to Harry M. Miller.

Miller promised to get the band at least 2,500 pounds in work for the first six months, signing over his Mark VII Jag to Morrison as a guarantee. He delivered by putting them to work on the Auckland club circuit, doing three or four shows a night every weekend at clubs like the Sorento, St Seps, The Arabian, The Colony and Trillos.

By this time the Quartet was Morrison, Merito, Wharekura and Noel Kingi, who had replaced Howell.

Miller re-recorded ‘Battle of the Waikato’ for his La Gloria label, which motivated Stebbing to get out and promote his (better) version harder, which didn’t hurt the band.

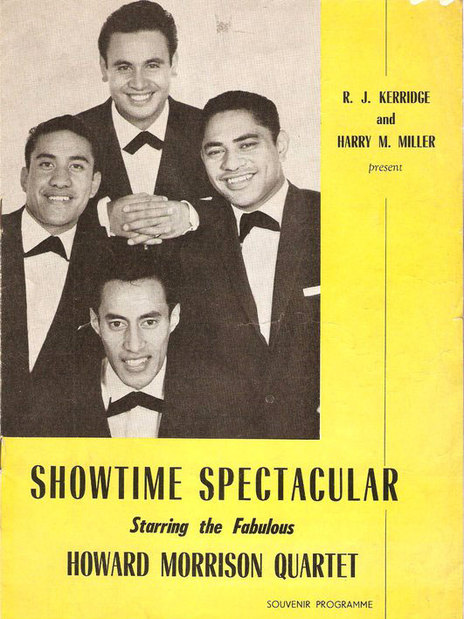

Miller also got the band into the National Film Unit studios in Wellington to produce two short films each containing three songs, which were shown as shorts in Kerridge Odeon theatres, shortly before he sent the band on a national Showtime Spectacular tour of the same theatres.

‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ tapped into the controversy about Māori being excluded from the All Black tour to South Africa.

To launch the tour, the band parodied another Lonnie Donegan song, ‘My Old Man’s A Dustman’ – ‘My Old Man’s An All Black’ tapped into the controversy about Māori being excluded from the All Black tour to South Africa. Recorded in primitive conditions at the end of a live show at the Pukekohe Town Hall, it went on to sell 60,000 copies.

The same tactic was used for the next Showtime Spectacular tour – the story of repeat prison escaper George Wilder was told to the tune of ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’.

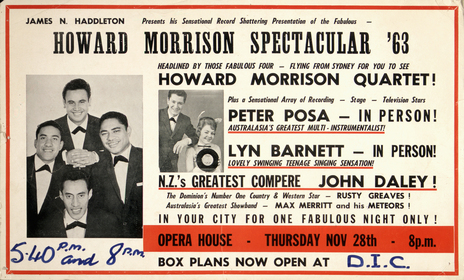

The tours were top-heavy with talent – as well as the Quartet there would be Toni Williams and the Tremellos, guitarist Bob Paris, female impersonator Noel McKay, singer Kim Krueger, and various local acts from each centre.

Miller also took his charges to Australia, booking them into a vaudeville show, Nats in the Belfry, which played extended seasons at Tivoli theatres in Sydney and Melbourne.

While singing the same three songs night after night was frustrating, the experience taught the band a lot about stagecraft and showmanship, as well as giving Morrison the opportunity for some professional singing lessons.

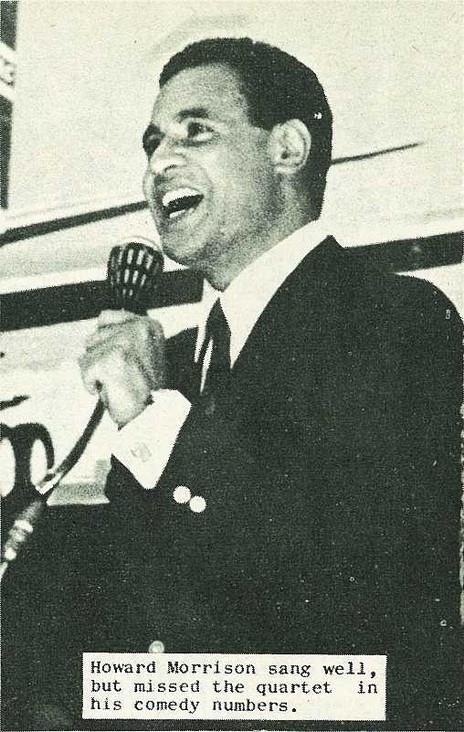

Some less-than-complimentary reviews from Australian critics also made Morrison rethink his role as front man, and the band used its extensive rehearsal time to hone its act, bringing the other members more into play.

Back across the Tasman the band toured extensively. Often they would go out in support of overseas acts like the Everly Brothers, then go back out and fill the same theatres as headliners.

By 1963 Miller was ready to take the Howard Morrison Quartet international. The Quartet didn’t want to go, partly for family reasons, partly from growing distrust at Miller’s business practices.

Miller went on to fortune, fame and occasional infamy in Australia. The Howard Morrison Quartet became a New Zealand icon.

In retrospect Morrison admitted the band was limited by a repertoire consisting of covers and parodies. With the Beatles emerging and changing the nature of the industry, international success outside the lounges of Las Vegas may have been tougher to grasp than Miller was counting on.

As Morrison put it, at the time of the breakup with Miller the Quartet were very professional as entertainers, very limited as musicians, and “out on our own” as crowd pleasers.

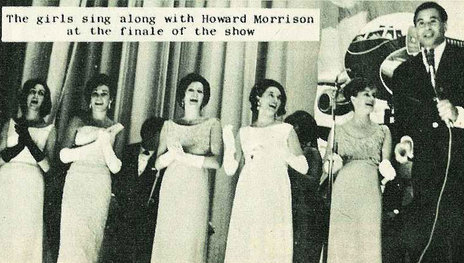

They showed off that crowd-pleasing aspect at their next major gig, touring the country with the Miss New Zealand contest run by southern entrepreneur Joe Brown and his son Dennis.

The competition had been struggling, but combining it with the Quartet brought in the crowds.

The first year they did the tour the winner, Elaine Miscall, went on to be Miss World runner-up, which brought in sponsors and endorsements in the following years.

Going solo

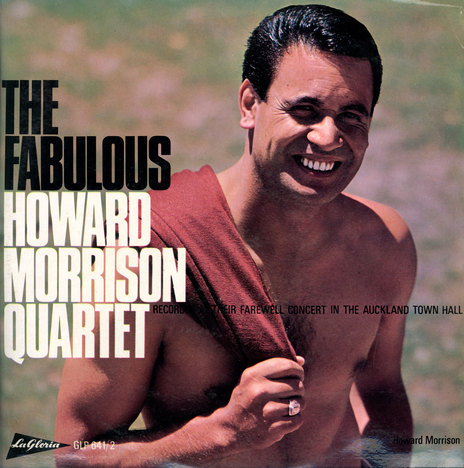

In 1964, after a second Miss New Zealand tour, Morrison felt the spark was going, and called a halt. Taking charge of the business side, he brought in Benny Levin as co-promoter for a farewell tour, which ended at the Regent Theatre in Rotorua on New Year’s Eve 1965.

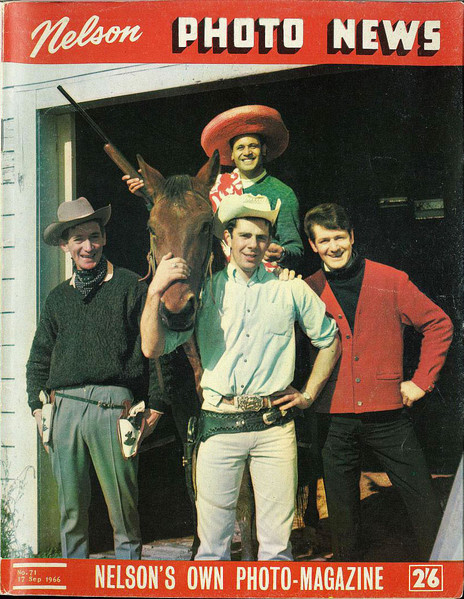

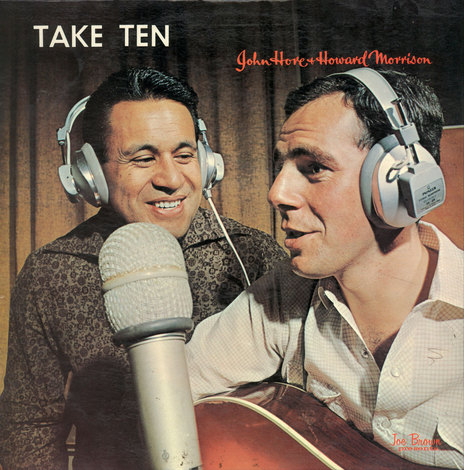

After the Quartet, Morrison did the Miss New Zealand tours as a solo performer, and also joined Joe Brown’s country and western tours alongside the likes of John Hore, Jim NcNaught, Peter Posa, Eddie Low, The Quin Tikis and Suzanne Prentice.

He also started appearing in films. The first role was as Kingi, a Māori shearer, in a low budget Australian movie, Funny Things Happen Down Under, that was also the film debut of 15-year-old Olivia Newton-John.

That gave Morrison the idea for what was billed as New Zealand’s first musical comedy feature film, ‘Don’t Let It Get You’.

That gave Morrison the idea for what was billed as New Zealand’s first musical comedy feature film, Don’t Let It Get You.

Produced and directed by John O’Shea, it also featured Kiri Te Kanawa, Australian star Normie Rowe, the Quin Tikis, Herma Keil and others.

Morrison lost money on the film, but it helped establish him as a solo act.

He started getting work in Asia. Between 1968 and 1976, when disco spelled the end for the cabaret singers, he played at almost every Hilton in the East, as well as extended seasons in Hawaii – including parts in two episodes of Hawaii Five-O.

Along with the music he was promoting New Zealand, something that got him an OBE in 1976.

When he wasn’t overseas or on one of the Joe Brown tours he was able to commute from his Rotorua home to regular weekend work in Auckland at Bob Sell’s Logan Park cabaret and at the Station Hotel.

For his 40th birthday on August 18 1975, Morrison reunited the Quartet for a one-off concert in the Christchurch Town Hall, which turned into two concerts because of demand for tickets.

It was filmed for a television special, but the tape was accidentally wiped before it was broadcast.

Giving back

The shift into his fifth decade and his OBE encouraged Morrison to consider a new direction, what he called “giving something back”.

The opportunity came with the appointment of Kara Puketapu as the Secretary for Māori Affairs. As the first Māori in the position, Puketapu looked for ways for Māori to stand tall – his policy was called Tu Tangata.

It included bringing people into the department who had demonstrated either cultural skills of commitment to their communities.

Morrison was taken on as youth development consultant, and set about developing programmes to get into schools to address high levels of Māori under-achievement.

This involved going into schools with a team of people, talking to students as a group and individually about their aspirations, and pointing out the paths to get there.

They also ran youth wānanga, bringing young Māori on to marae, often for the first time in their lives.

To promote Tu Tangata nationally as a force for positive change rather than the exercise in separatism its critics were alleging, Morrison again reunited the Quartet for a national tour, with Toni Williams standing in for Wi Wharekura.

By 1981 Morrison’s work as a public servant had taken him out of the limelight, and he also had growing doubts about the willingness of government to keep funding all the programmes coming out of Tu Tangata, which also included Kōhanga Reo and the Maatua Whāngai programme for getting Māori children out of state care.

The single ‘How Great Thou Art’ came out in time for Christmas. It went straight to No.1 and stayed there.

The invitation to appear in the command performance for the 1981 Royal Tour left Morrison wondering what he should sing. The organisers were alarmed at his choice of a hymn, but thought if anyone could pull it off, it would be him. The single ‘How Great Thou Art’ didn’t come out until three months after the show, in time for Christmas. It went straight to No.1 and stayed there.

It also led to Television New Zealand to commissioning The Howard Morrison Special, filmed live at the Founders Theatre in Hamilton in September 1982.

He continued to work for the Department of Māori Affairs, pushing for more Māori involvement in business, broadcasting and tourism among other initiatives.

In the 1980s he served a three-year term on the Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand board, in which he challenged the lack of commitment not just to Māori culture but to pop music in general.

In 1988 Morrison went back out on the road with a band, playing chartered clubs. It reconnected him with a core audience, people who used to see him in the 60s and 70s and were now club members.

In 1989 Morrison featured as the target for an episode of This Is Your Life, rekindling interest in his work, with a national tour hastily booked to take advantage.

Arise Sir Howard

Morrison was knighted in the 1990 Queens Birthday Honours. One of his first acts as Sir Howard was the Ride for Life, a horse trek around New Zealand to raise funds for the Life Education Trust.

A heart attack in 1991 slowed him briefly, but Morrison continued his mix of performing and public service until his death on September 24, 2009.

Morrison may not have been the best singer in the business, and his musical waywardness could be a challenge for his bands, but as an entertainer he was superb.

His willingness to take time out from music to give back not just to Māori development but also other worthy causes amplified his position as a performer.

New Zealand music would be much the less without him.