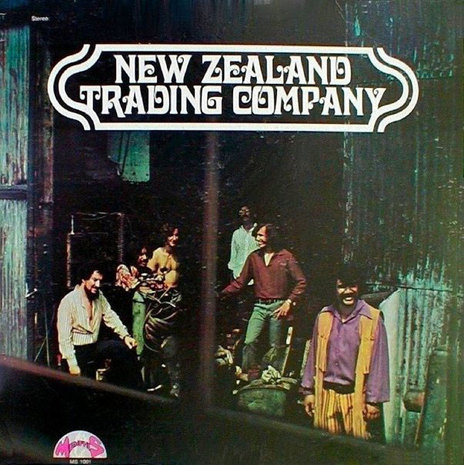

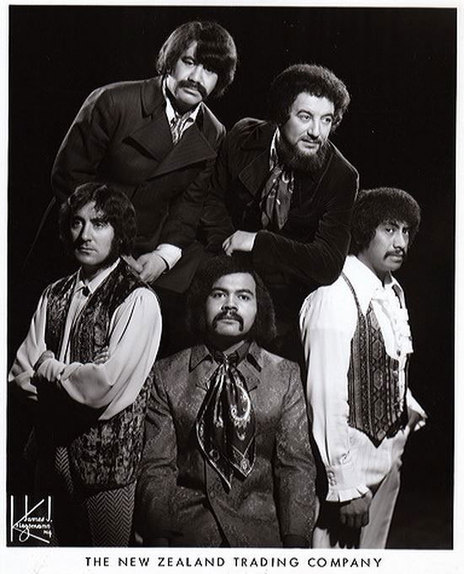

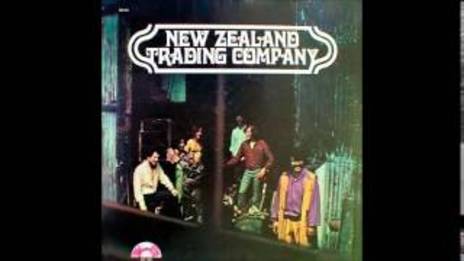

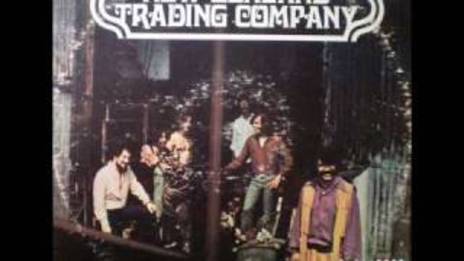

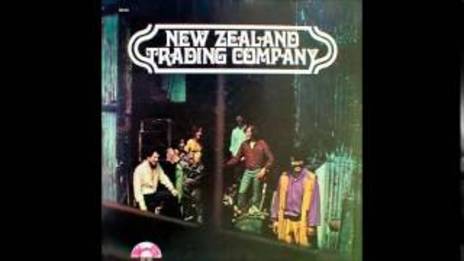

The LP’s dark cover gives away few details. On the front, the band is brooding, barely visible. The back just lists the song titles, the composers, the producer, engineer and the address of the record company. The New Zealand Trading Company album came out on the Memphis label, a short-lived firm with its own studio down the road from the one in which Dusty Springfield sang of her preacher man and Elvis of suspicious minds.

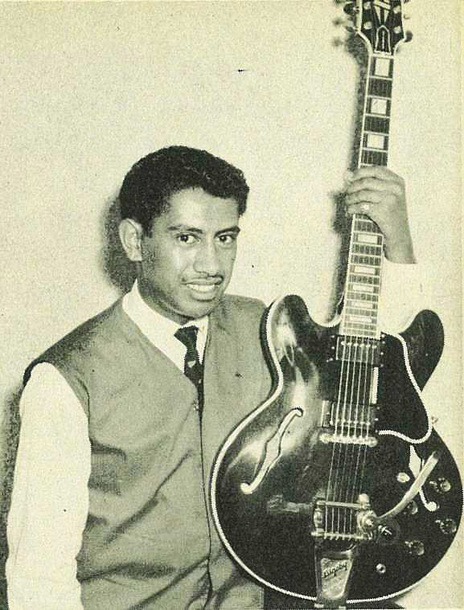

The story of the New Zealand Trading Company begins in Gisborne in 1958. Born in 1944, Thomas Kini (Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki) was a 14-year-old guitarist who grew up listening to his father playing violin, guitar and lap steel – and to his collection of big band jazz. His brother Martin was a member of the Kini Quartet (‘Under the Sun’). In 1960, aged 16, Thomas Kini moved to Wellington to join the fledgling Māori showbands.

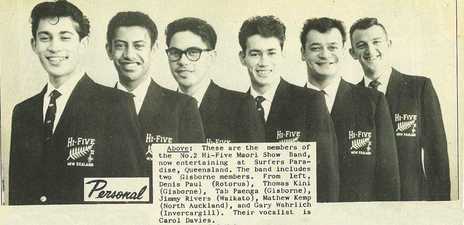

The first Māori showband was the Maori Hi-Five, who began in 1957 as a rock and roll band called the Hi-Five Mambo. They were so successful that the Hi-Five company – run by expat Britons Charlie Mather and Jim Anderson – formed a second group, the Maori Hi-Quins. Led by the Mambo’s founder, bassist Ike Metekingi, the original Hi-Quins were Thomas Kini on rhythm guitar, pianist James Tuatara (AKA Jimmy “Junior” Rivers), Matthew Kemp on lead guitar, Tab Paenga on sax, and Peter Wolland on drums.

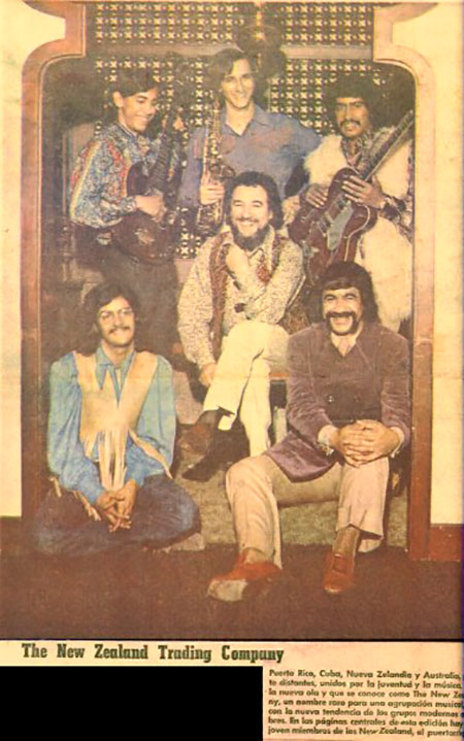

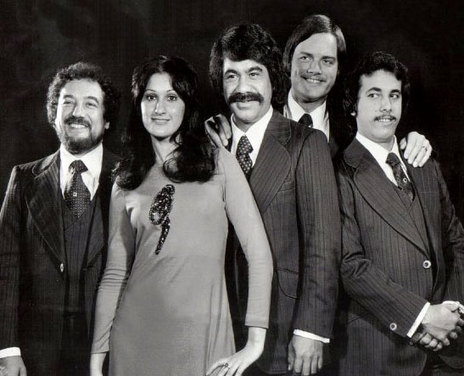

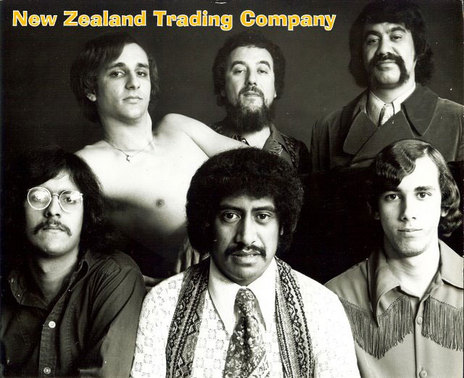

the new zealand trading company emerged from the Maori hi-quins, and became multi-cultural.

The Hi-Quins moved to Australia early in June 1960, with Rim D. Paul on board as singer and bassist. They had residencies at the Chevron Hotel in Surfers Paradise and the Rex Hotel in King's Cross, Sydney. While in Sydney, Kini developed an interest in jazz and studied music. Later that year the Hi-Quins moved to England. Besides Kini on lead guitar, Paul as singer, and Rivers on piano, the group now featured singer-pianist Kawana Waitere from Putiki (a school friend of Paul at Te Aute College), and Eddie Nuku from Taranaki on bass. Plus, there were two Australians: drummer Neville Turner and singer Lynn Rogers.

The Hi-Quins toured in Britain, Germany, Spain and Sweden. In London they played the prestigious Pigalle club, and were seen by Sammy Davis Jr. He encouraged them to move to the United States. The Gisborne Photo News reported on Kini’s progress in September 1964: “In less than five years, the show band has played in dozens of overseas countries, including Australia, England, Europe, and, more recently, the United States and Canada. When Thomas returns to America, he will be playing with the band for six weeks in New York, and will then go to South America and back to England.”

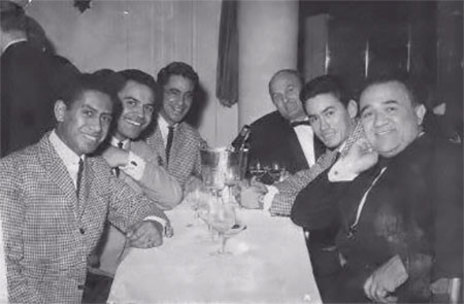

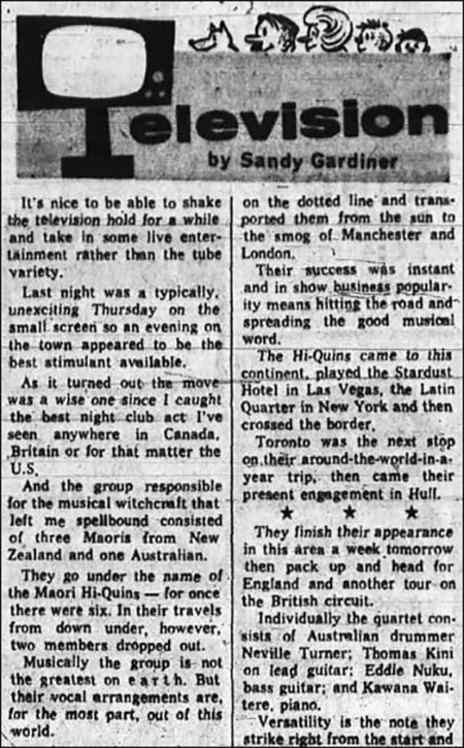

They performed at venues such as the Stardust Resort in Las Vegas and the Latin Quarter in New York. In 1965 a reviewer in Canada raved about the Maori Hi-Quins’ appearance on a local TV show. “The group responsible for the musical witchcraft that left me spellbound consisted of three Maoris from New Zealand and one Australian … Musically the group is not the greatest on earth. But their vocal arrangements are, for the most part, out of this world. Their material ranges from native ‘action songs’ to jazz and rhythm’n’blues with a shake of rock’n’roll thrown in for good measure. And although the quartet readily admits a dislike for rock’n’roll, they put their hearts and their hands professionally into all they do.”

The frenetic touring schedule of the band is reflected in a letter that Paddy Te Tai of the Maori Hi-Five wrote to the magazine Te Ao Hou from Las Vegas in September 1966: “Just finished out here at the Thunderbird Hotel are the Maori Hi-Quins – Thomas Kini, Gisborne; Kawana Waitere, Putiki; Eddie Nuku, Auckland; and Lynn Alvarez and Neville Turner of Australia. These boys have recently returned from five weeks in Hawaii, are now in Tuscon, Arizona, and leave shortly for Montreal, Canada.”

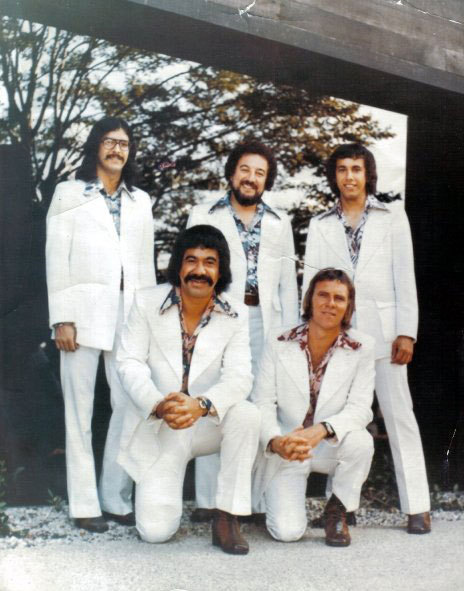

By 1969 Kini, Nuku, Waitere, Turner and Alvarez were based in Chicago with a new name: the New Zealand Trading Company. They recorded a single for Cadet Records, an offshoot of the legendary Chess label. In Cadet’s catalogue, number 5637 is credited to the New Zealand Trading Company performing Kini’s ‘Could Be’ b/w ‘You’ – but it has left little trace.

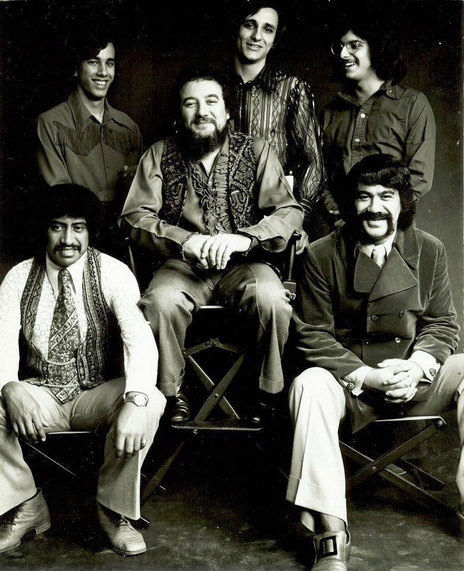

Here the story gets more complicated – and more multi-cultural. Alvarez, Turner and Nuku left, and Kini and Waitere joined forces with an English pianist, Maurice Moore. They had possibly met in Australia earlier in the 1960s, when Moore worked for JC Williamson theatres. (Moore visited Auckland with the band of a touring My Fair Lady show; his wife Patricia played Eliza, the lead role. Also on the tour was a UK dancer, Barry Kennedy, who became a close friend and would later write lyrics for several New Zealand Trading Company songs.)

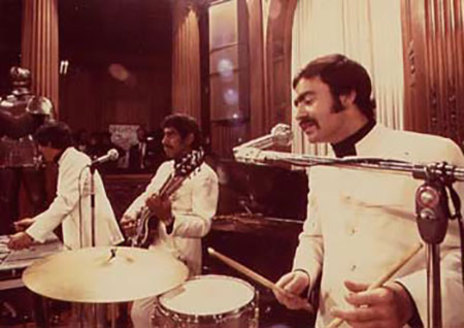

While playing in Miami, the NZTC recruited three Puerto Rican musicians from a band called Abram Shoo: Cuban-born guitarist Jorge Casas, drummer Gonchi Sifre, and pianist/singer-songwriter Alberto Carrion. (Just out of their teens, the trio had briefly backed Janis Joplin one night in 1969, when they were playing a residency at a Puerto Rican club and she stepped on stage.)

They appeared on The Johnny Carson Show twice in 1969, and secured residencies at Playboy clubs around the world.

The sound of the second New Zealand Trading Company was inevitably cosmopolitan, a mix of high-end, arranged pop like the Fifth Dimension with more edgy styles such as jazz-fusion and funk. They appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show twice in April 1969, and were booked for residencies at Playboy clubs around the world. In New York, they performed in Shepheard’s nightclub in the Drake Hotel, one of the most fashionable rooms in the city. The Drake was frequented by musicians ranging from Frank Sinatra and Jimi Hendrix to Led Zeppelin (who once had $200,000 cash stolen from the hotel’s safe-deposit box).

While performing at the Playboy club at Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, the New Zealand Trading Company was discovered by Ronnie Hoffman. He was friends with a couple from Memphis who were involved in the local music business, Natalie and Seymour Rosenberg. Natalie ran a booking agency and was an independent record producer who had worked in the Stax studios. Seymour was a well known local lawyer – and big band musician – who often represented artists battling their record companies for royalties. For 15 rollercoaster years the couple managed country legend Charlie Rich.

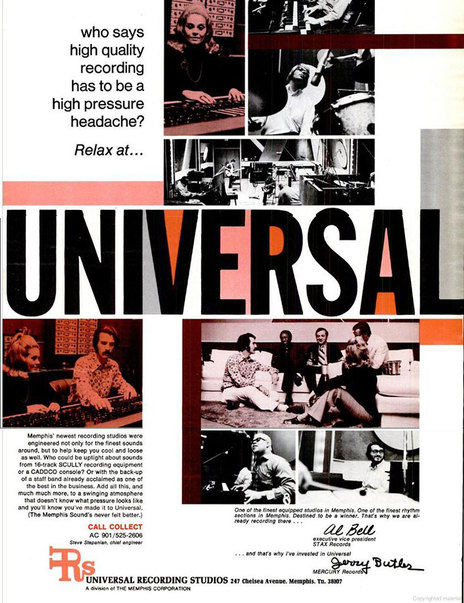

In 1969 the Rosenbergs launched a label, Memphis Records, and built a studio that emulated the proportions and shape of Stax, a former cinema. The Rosenberg’s Universal studio was situated on Chelsea Avenue, near Chips Moman’s American studio where Elvis Presley and Dusty Springfield and others recorded many hits in the late 1960s. Seymour had been Moman’s original partner in American.

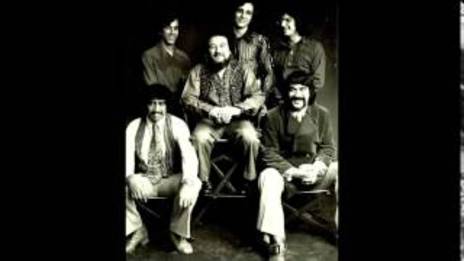

On Hoffman’s recommendation, the Rosenbergs signed the New Zealand Trading Company, recorded them at Universal in 1970, and released their album on the Memphis label later that year.

Natalie Rosenberg produced the album, with the studio’s house engineer Steve Stepanian at the desk. Speaking on the phone – long distance from Memphis, Tennessee – Natalie remembers the New Zealand Trading Company fondly. “I really loved those guys,” she says. “They were so respectful and so professional. They came to Memphis, rehearsed at my house, then we went into the studio. The sessions just took a few days, from what I remember. But I recall the looks on everybody’s faces when we had the playbacks: the sound of the studio, the sound of the entire album. I’m prejudiced, of course, but it was perfect. I wanted every instrument to be heard, for every one of those great musicians to have their moment.”

The concept for the album cover came from Natalie. Wanting to play on the band’s “trading company” name, she took them down to the Mississippi River, where they were photographed among barges, and walking along the riverbank. “It could be anywhere in the world, but the idea was that they were the New Zealand Trading Company.”

Once the album was recorded and mixed – the date September 1970 is on the cover – the Rosenbergs tried to get local radio play, but struggled. “The problem was, at that time, there was no niche for them to fit into,” says Natalie. They weren’t Top 40, they weren’t R&B, they weren’t jazz. “They were ... I don’t know what they were. No one knew. Obviously that was the problem for Leonard Chess. We couldn’t find a place where they could sit musically. They were a showband really.”

Their emphasis was on entertainment? “Absolutely. These guys were rockin’.”

Forty-five years after the sessions, Natalie Rosenberg has few detailed memories of the sessions. She thinks it was Kawana Waitere who sang ‘Hey Jude’, the album’s only non-original. “Which was just awesome.”

By getting on to Memphis radio, they hoped the band would be picked up nationally by a major record label. “We were looking for airplay first, locally, but the radio programmers couldn’t find them a niche. They would love the album, the players, the music. But it was a time when rock’n’roll and R&B and country – we always had country in the South – they were dominating. So where do you put the New Zealand Trading Company? That was the problem.” The music was too sophisticated? “That’s right.”

After the album’s release, Natalie lost track of the musicians. “And that was always very sad for me, because I believed in them so much. And I thought they were all such beautiful people, it saddened me that we couldn’t do anything for them at that time.”

By October 1970 the Rosenbergs had sold their studio, and the Memphis label went quiet. So too did the New Zealand Trading Company. “I always believed that they would have a huge future ahead of them. I didn’t know whether it was in the record business, perhaps as a showband going around the country. And eventually that they would find their fame and fortune, which is what we all hoped for. Their music was just a joy, and I listen to it to this day.”

After the demise of the New Zealand Trading Company, Waitere was briefly a member of nightclub band Commonwealth with Maurice Moore; he died in 1997. Jorge Casas went on to become Gloria Estefan’s musical director, Alberto Carrion a highly regarded Latin composer, and Moore has had a long career leading club bands.

Kini is said to have recorded with Minnie Ripperton and Donny Hathaway, and performed with Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock and George Benson.

Thomas Kini was in Miami in the early 1970s when the leader of the Latin band Hondo Beat heard him play and invited him to come to Chicago and join the band. He was recruited as a bassist, so bought an electric bass and became a sought-after player in Latin, jazz and soul sessions. Kini is said to have recorded with Minnie Ripperton and Donny Hathaway, and performed with Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock and George Benson.

Over the next 30 years, Kini became a stalwart of the Chicago jazz scene, and a local champion of Māori culture. He died of a heart attack in Chicago on 5 April 2004. “He just loved this city and all of its energy,” his fiancée, Sonya Walker, told the Chicago Tribune. “He loved music and he loved his heritage.” Lynn Rogers, a former member of the Maori Hi-Quins, said, “The world is a sadder place without the wide smile of Thomas Kini. He was without doubt one of the finest human beings I have had the pleasure of knowing and his musicianship was extraordinary.”

Maurice Moore, the leader of the New Zealand Trading Company, recalled in 2012, “It was a fantastic group – more suited to live performances than recording hits. I spent the best years of my life with these guys.” Moore died in November 2019, aged 90, 10 months after Jorge Casas, who was 69.