Margaret was born in 1931 in Thames but spent most of her childhood and later life in Gisborne. Her mother, who the family remember as Nanna Jones, was the daughter of Swedish and Irish immigrants. Her part-Māori father wasn’t around much during her childhood. It was a hard life for a solo mother at the height of the Depression, and Margaret and her older sister spent some time in foster care.

Music was her refuge from an early age, though there was never enough money for an instrument nor lessons. Instead, the Catholic nuns who taught piano to paying students would sometimes allow her to sit in and observe their classes, after which she would rush home to practise on a crayon keyboard she had drawn on a kitchen bench. On her silent instrument, listening only to the sounds in her head, she was still somehow able to develop her theory and technique.

With no piano, she practised on a crayon keyboard she drew on a kitchen bench

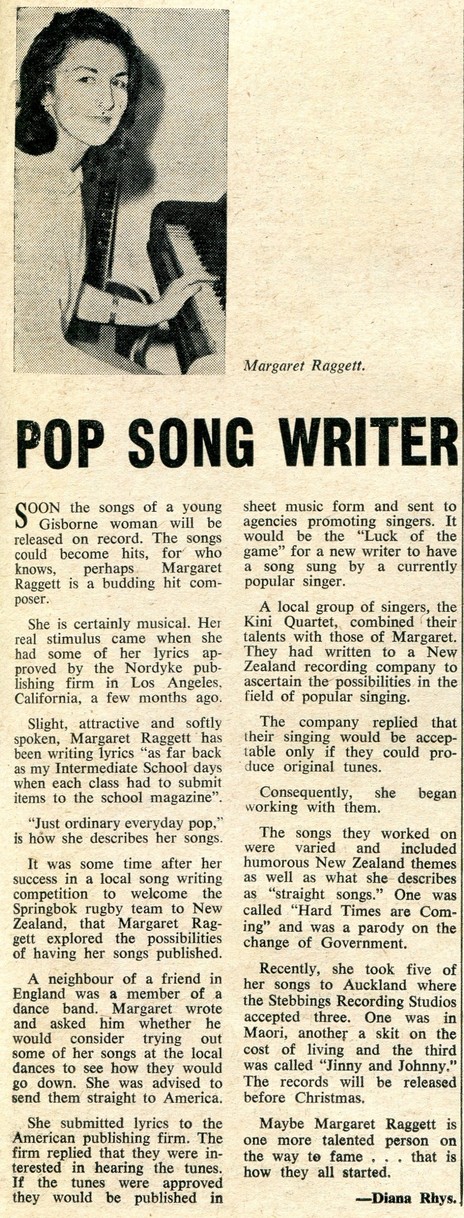

When she was 14 her mother, who had by now married Eli Jones, was at last able to buy her a secondhand piano, and Margaret quickly passed her grades. By this time she had already begun writing her own songs. At intermediate school, her class was asked to submit items for the school magazine, and she contributed an original lyric.

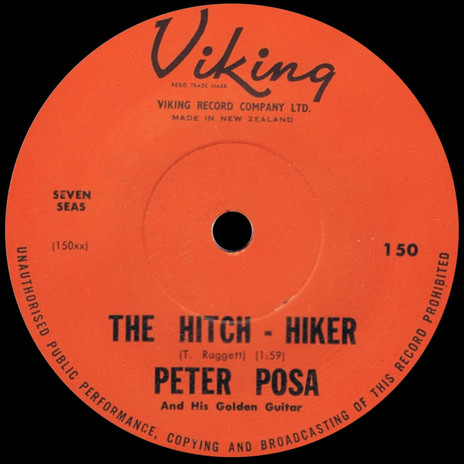

When she was 16 Margaret met Bill Raggett, a mechanical engineer. He was working at a local car yard and would try to impress her by driving past her house, each day in a different car. Who knows whether it was this ploy that won her heart, but several of her songs would feature cars in their lyrics. Ironically, one of her most popular numbers, ‘The Hitch Hiker’, was about a man who had no car at all.

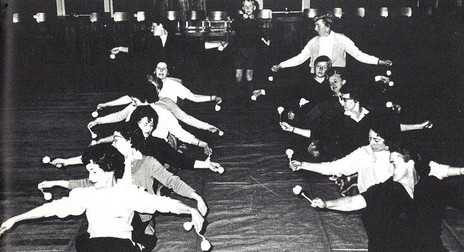

Bill gave Margaret the nickname Tiny, a name everyone came to know her by. The couple married the following year and moved into their first home in Fox Street. Bill went to work as a fitter and turner at the nearby Kaiti Freezing Works. At weekends the couple would party with Bill’s workmates, which always involved music. Bill would bring a flagon, Tiny a guitar, which she had taught herself to play. Bill loved music too and could blow a harmonica but was chiefly known for his strong singing voice. The partying would usually take place in living rooms, often their own. Sometimes it would be on the nearby Te Poho o Rawiri marae.

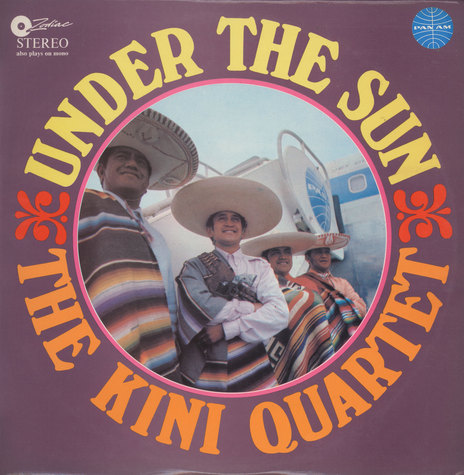

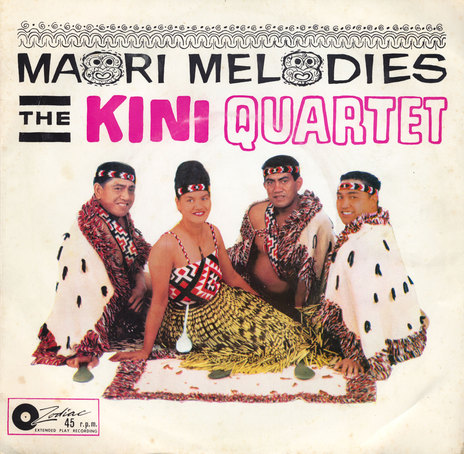

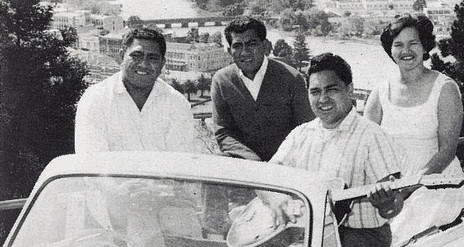

It was through these informal musical gatherings that Tiny and Bill, who both identified as Pākehā, formed close bonds with the local Māori community including The Kini Quartet, a local vocal and guitar group who had been winning talent quests and were now hoping to make a record. Eldred Stebbing, of the Auckland-based Stebbing studios and Zodiac record label, had expressed an interest in the group, but only if they could come up with some original material.

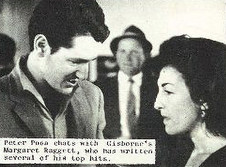

Tiny had been working hard at her songwriting and had entered a few competitions, including one sponsored by local radio station 2XG to write a song welcoming the British Lions football team to Gisborne on their 1959 New Zealand tour. Not feeling confident enough to sing her own song, she enlisted the help of The Kini Quartet, and won the contest. The Quartet had found their songwriter, and Stebbing, impressed by Margaret’s material, sent guitar wizard and top-selling Zodiac artist Peter Posa to Gisborne, along with a recording technician, to arrange and produce the first Kini Quartet record.

Released in 1962, both sides of the single features a Raggett composition. The A-side, ‘Hard Times Are Coming’, has Posa playing a rockabilly-style guitar and revolves around a comic conversation between a Māori and a Pākehā about how each will deal with the rising cost of living. The Pākehā worries he won’t be able to afford to eat and drink, but the Māori isn’t bothered; he says he’ll catch paua and make home-brew. As for cars, “As long as we’ve got horses / who needs those big Bel-Airs?”

Like some of Howard Morrison’s material from the same period, or the later routines of Billy T. James, the racial characterisations in the song might be deemed inappropriate today, but at the time they provided a way of understanding, celebrating and defusing cultural differences.

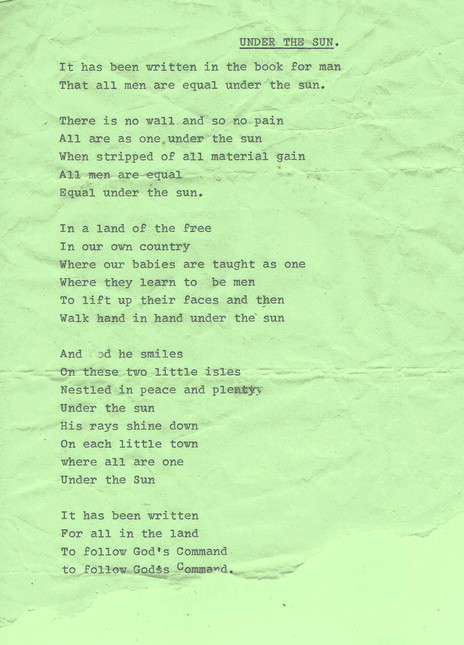

‘Under the Sun’s te reo title ‘Te Kotahitanga’ can be translated as ‘The Unity’ or ‘Oneness’

The B-side is the first recording of the song that would eventually become a top-selling hit in its English language version as ‘Under the Sun’, but here it is sung entirely in te reo. A song of unity and justice, Margaret wrote the original lyric in English, with Bill contributing several of the lines. Having spent time on the marae, Margaret and Bill were reasonably fluent in te reo and she wrote the Māori lyric with her friend, the influential Māori educationalist Te Maaka Jones. The song’s te reo title, ‘Te Kotahitanga’, can be translated as ‘The Unity’ or ‘Oneness’, a name it shared with an organisation set up around the same time to teach cultural roots and self-worth to young Māori returning to the East Coast after spending time in the cities, where many had experienced homesickness and racism.

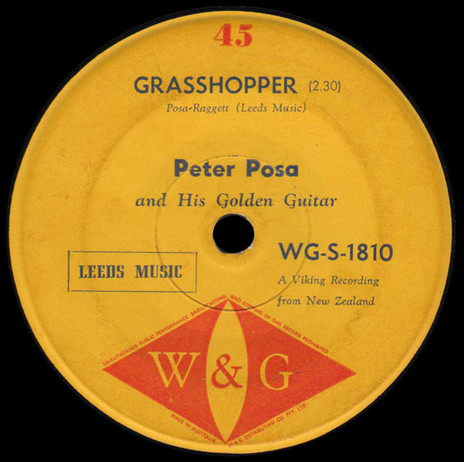

Stebbing saw potential for other artists in Tiny’s material and flew her to Auckland so he could hear more of her songs. Posa was impressed too, though he would not record any of her tunes himself until he had left Stebbing for the Viking label, when he would record several Margaret Raggett compositions including her instrumental ‘Grasshopper’ and a guitar-led version of ‘The Hitch Hiker’. She and Posa became good friends and remained so throughout their lives, sometimes working on guitar arrangements together and experimenting with electric guitar effects such as tape delay.

On the flight back from Auckland, Tiny wrote what would become the second Kini Quartet single, ‘Jenny and Johnny’. The song about two estranged lovers was inspired by the geography of her hometown, and the two rivers – the Taruheru and the Waimata – which join to form the Tūranganui. In the song, the rivers symbolise the couple’s parting and eventual reconciliation as they flow together to the sea. To the Quartet’s Joe Williams the song was particularly special. “There’s not many songs that are written about your old hometown,” he said in an interview for Gisborne's Tūranga FM in the late 1980s. “She had such a fabulous sense of loving for the land, the rivers. She is an ecologist and a brilliant composer and writer.”

A sequel to ‘Jenny and Johnny’, ‘He Didn’t Know’ would appear in 1964 on the Kini’s fourth single release, backed with the Kini’s recording of ‘The Hitch Hiker’, while the B-side of ‘Jenny and Johnny’ was Tiny’s musically adventurous ‘Storm Girl’, with its unexpected modulations and quick switches between bolero and swing rhythms. But the Quartet’s biggest hit and the song that would become Tiny’s best-known and most recorded composition was ‘Under The Sun’.

It begins with a long chord and a solemn proclamation.

It has been written in the Book for Man

That all men are equal under the sun …

Martin Kini’s Biblical baritone is soon joined by a guitar playing a familiar jinga-jick rhythm – the classic Māori strum – while the voices of Joe Williams and Esther and Barney Taihuka slide into harmony behind him as he imagines a land, free from war, inequality, poverty or any of the other ills of the world.

There is no wall and so no pain

All are as one

Under the sun

In the land of the free in our own country

Where our babies are taught as one …

The gentle sweetness of the harmonies and innocent idealism of the lyric are, as Redmer Yska says, “strangely touching … albeit with a sting in its tail”.

‘Under the Sun’ is a protest song of the subtlest kind

For many Māori at the time there was a marked contrast between the utopia described in the song and their own lived experience. ‘Under the Sun’ is a protest song of the subtlest kind. It doesn’t bother to point out the injustices that are the reason for its being written in the first place. In the manner of John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ (composed nearly a decade later) it goes straight to the utopian alternative, depicting a perfect land, with a gentle optimism that flows from its lyric to its sweet melody.

The Quartet’s recording of ‘Under the Sun’ became a national hit in 1963, and would also see some success in Australia, where the Kini’s based themselves for a period in the mid-1960s. It would be recorded by several other artists, in both its English and te reo versions. Daphne Walker recorded it, as did The Convairs, while the Kinis version was reissued several times over the years and became the title track of their only album.

The Convairs also recorded another Raggett composition, ‘Handful of Dirt’: an allegorical tale of land and war. Though the Kini Quartet never released a recording of the song themselves, they cut a demo with Tiny for a songwriting competition, and Joe Williams named it as a personal favourite. He believed that had they released their own version it would have been “even greater than ‘Under the Sun’”.

“It is written for today,” he said in the late 1980s, some 25 years after ‘Handful Of Dirt' was first heard. “Now. Jobs for the people? Where? In the soil. Where is the soil? Around the pā. The concept of putting your hands down in the soil, picking it up and letting it go through your fingers. That’s everything to me. You put a seed in it, a little bit of water, and up comes a plant. You eat the plant, you carry on surviving. You live. To Māori – or to me anyway – the soil means everything.”

Though Tiny never thought of herself as a performer, she and Bill were a crucial part of the Gisborne musical scene. Every summer the Beach Carnival would come to the Gisborne Soundshell and the Raggetts would be there, on stage and off. Out of town musicians would visit the couple at home, both to socialise and to see whether Tiny might have any new material for them. Visitors to the house included Howard Morrison, Lou and Simon, Gray Bartlett, Brendan Dugan, as well as international stars including Gene Pitney, Millie Small and Clarence “Frogman” Henry.

She would make her own demo recordings. She enjoyed technology, and had an imposing pair of reel-to-reel tape recorders which sat in the living room of the Raggett’s 90-square metre state house, along with her electric guitar and piano. Her three children, Bill, Terry and Tina, recall numerous occasions on which they would wake in the night to the sound of their mother making music. Their father, with his rich voice, was often cajoled into singing on the demos.

The children all recall that their mother slept very little: three hours a night on average, they reckon, and some nights not at all. When she wasn’t practising, composing or recording her music she was pursuing her other passions: prose writing and photography. She wrote short stories, and if it wasn’t the sound of a piano or guitar that was keeping her sons awake at night it was the relentless clack of her typewriter. She became a Gisborne correspondent for New Zealand Newspapers, publishers of the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly and Auckland Star, and contributed to both publications. She also owned a 35mm camera and would take photographs, sometimes to accompany her articles but also to satisfy her own artistic impulses. The bathroom doubled as her darkroom, and the bath would often be commandeered for developing her prints.

Meanwhile Tiny’s mechanically minded husband Bill had invented a tool that radically sped up the process of grafting plants in nurseries. He founded Raggett Industries Ltd., which remains a family business to this day, exporting the Graftech and Topgrafter all over the world. Tiny became the administrator, running the company’s office.

She was generous and gregarious, though she could show a feisty side when provoked

She was generous and gregarious, though she could show a feisty side when provoked. Once, at a civic event, she believed the mayor of Gisborne, with whom she was sharing a table, had behaved inappropriately. As son Terry heard it, “she stood up, screamed at him and clocked him one in front of a huge crowd.”

In the 1970s her songwriting output began to slow down, though she continued to play and keep up with new music, as well as give guitar lessons to students who would come to the house.

She was early to spot that her youngest grandson, Ryan, shared her talent and enthusiasm for music, and began teaching him. It wasn’t just cowboy chords either. The first songs he learnt from her were ‘Stairway To Heaven’ and ‘Riders On The Storm’. Ryan, who is currently active in the Gisborne music scene as a bass player with blues rockers Lazy Fifty and experimental psychedelic band Subset BC, says: “It was amazing how progressive she was with her musical tastes. She would talk to me and tell me how impressed she was by The Beatles and their songwriting, how they would clearly know their musical theory, that they knew the rules but knew exactly when to break those rules as well, that those were the moments that made their songs special. Her knowledge of music was really strong and she could identify all of those little features within songs, and then put them into her own songs as well.”

Singer Joe Williams credited the success of The Kini Quartet, in large part, to Margaret Raggett’s talents as a songwriter. Interviewed in the late 1980s he said: “Everything we recorded of Tiny’s went a long way and did things for us and for the [Stebbing] company, and for music in general, and for Gisborne. I’ve got to thank that woman for a career spanning over 27 years of my musical life.”

Ryan Raggett remembers his grandmother for her music, her extraordinary creative drive, and her kindness. “It’s been said amongst the family that, you know, she had such a tough childhood, she didn't get to actually be a child and that she lived it through her grandkids. So a big part of me hanging out with her was going down to the local Toy World, and she was more of a kid than I was in there, looking at and playing with all the toys. She had a real, beautiful, childlike nature. And that genuine love and joy of life.”

Margaret (Tiny) Mary Raggett died on 27 July 1999.