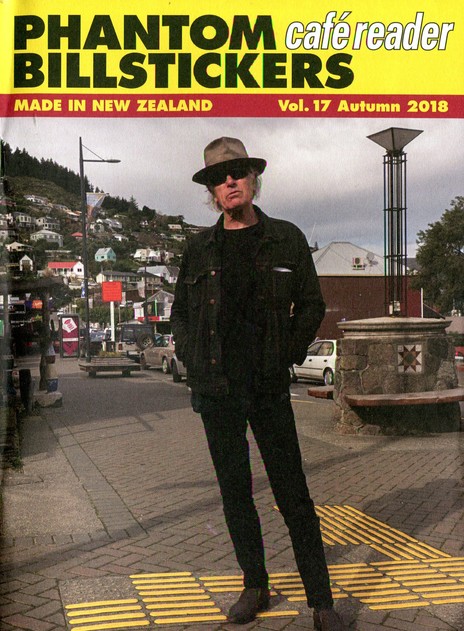

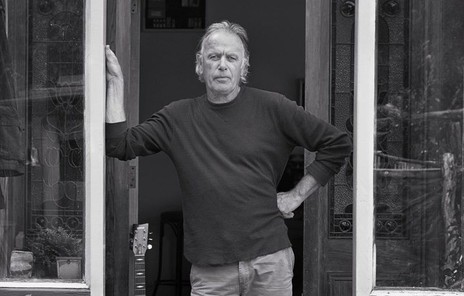

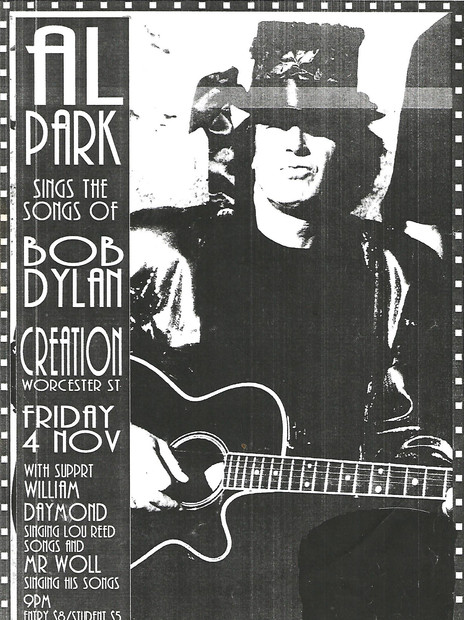

Rhythm guitar is Al’s band instrument (“I’ve always been a strummer”) coupled with his silent partner and inspiration: a deep-set knowledge and sharp recall of popular recorded music, which came in handy when he ran the secondhand section of key Christchurch shop, Echo Records. As the founder of two prominent city venues, Mollett (aka Mollet) St and Al’s Bar, and as booking agent he has promoted scores of performers, and provided a stage for international acts.

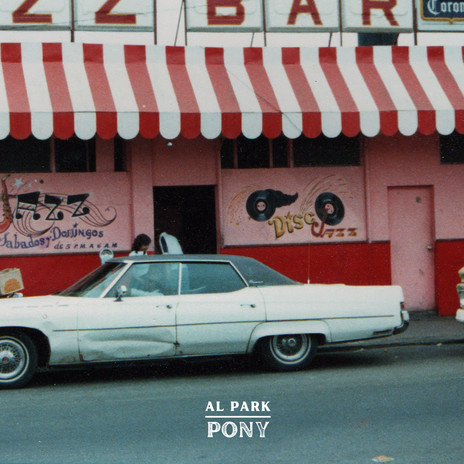

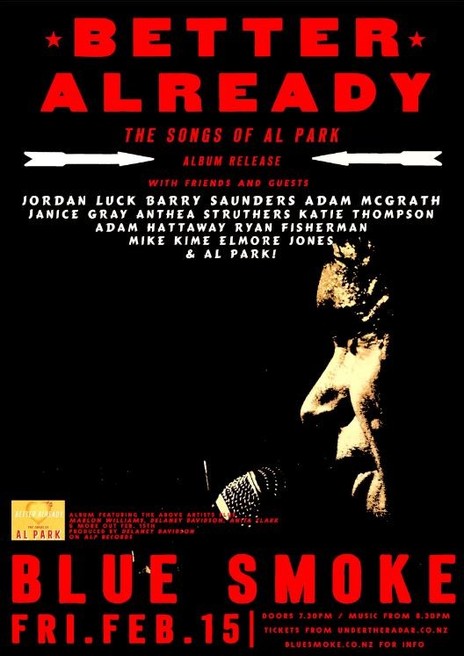

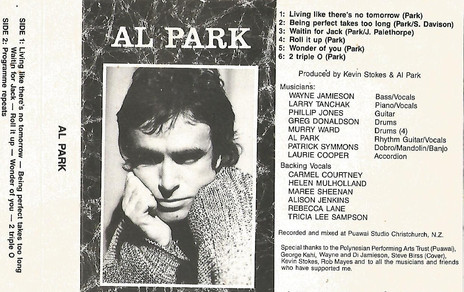

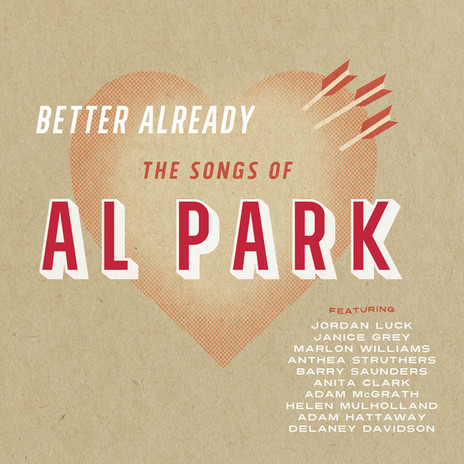

Music has always driven Al’s pursuits one way or another, whether entrepreneurial, performance orientated, mentoring or simply his choice of friends and associates. The affection in which he is held by his peers is evident in the list of performers who needed no persuasion to sing on Better Already: The Songs of Al Park, a 10-track release distributed through Southbound in 2019.

Music has always driven Al’s pursuits one way or another, as an entrepreneur, performer, mentor or friend.

Urged by friend Will Davie, who offered financial help to record his songs, Al said, “There’s no point in doing that, because it’s not going to sell. You’d be wasting your money.” Will suggested Al ask his friends if they’d want to sing the songs and Al put it back on Will to do the asking, because he felt awkward. Long story short, one by one they all said yes.

Al has lived in Lyttelton for decades and this edgy port town with the large musical heart is present on the album in people and place. Delaney Davidson was chief wrangler as producer and arranger, colouring the settings for the songs on piano and guitar with Mike Kime on bass, Ryan Chin drums, Elmore Jones guitar, Anita Clark strings and Paddy Long on steel guitar. Engineer Josh Petrie recorded it at Lyttelton’s Sitting Room studio through owner Ben Edwards’ goodwill.

Jordan Luck appears twice as does Marlon Williams – one alone and another with Barry Saunders and Helen Mulholland (Hotsticks). Adam McGrath (The Eastern) sings two – one with Adam Hattaway; Anthea Struthers takes one; Davidson adds his gravelly growl on two songs, and silver-haired city grande-dame Janice Gray sings the closing track with Anita Clark.

“It was interesting to hear Delaney’s take on the songs,” Al says. “Not that it was substantially different, but he did all those things that turn a song into a real song and that’s why I love the album so much. Delaney has to take a lot of credit.

Al grew up in Naenae, Lower Hutt in a small street of private homes in a state-housing area. While his family lived modestly, some of the neighbouring houses were architectural with features and acquisitions a sociable, creative person might find aspirational. His mates lived in such a home, with a parent who was one-time chairman of the QEII Arts Council. They had music and art collections, a good stereo, and a tennis court where Al and his mates burned off excess energy.

By nine or 10, a back-seat ukulele was the singalong soundtrack to long car trips, and family get-togethers always featured his mother or uncles on the piano.

“I have vivid memories of Uncle Jack at the piano – beer at one end and ashtray at the other – pounding the keys and everyone would be singing those old-school classics like ‘I met my little bright-eyed doll/ down by the riverside …’. I think melodically they influenced me. I’ve always liked a popular song.”

He first encountered 45s by the Everly Bros, Buddy Holly et al at the house of his Titahi Bay cousin who played in Wellington band, the Tornados (“just looking at them was a cool thing”), and when he acquired his own guitar at 13 he would ride the dial on his little radio searching for songs. “It was 1962 and I was so into music. I used to listen to things like ‘Cotton-Eyed Joe’ [Arthur Pearce] on National Radio. It was fantastic.”

Acquiring a guitar at 13, he would ride the dial on his little radio searching for songs.

By the time he hit Naenae College his hunger for music was a major preoccupation, and by 15 he was importing albums unavailable in New Zealand, from old blues to Velvet Underground and The Band. “You’d fill out your order and a few months later a big bunch of records would come. It was so exciting.”

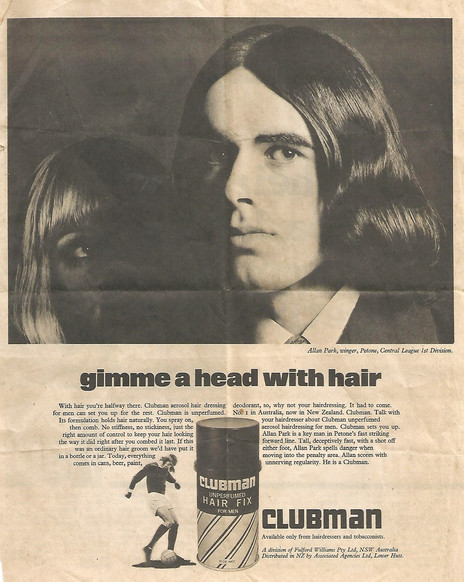

Sport took up the rest of his time, with athletics and middle-distance running giving way at about 18 to competitive soccer, playing as a striker or mid-fielder in the top 10 of the Central League.

“For me, football and music was the best combination. All the guys I used to hang with took the piss out of me being a sports guy, because it was not so groovy, but then they started coming down to the Basin on Saturday to watch me. I was kind of a weirdo, because I had long hair in 1968-69 when nobody in sports at that level had long hair. There was a photo of me on the back of the Evening Post, saying, ‘If you think George Best has long hair, you should see this guy.’ ”

After leaving school he moved to Wellington, where he laboured on the city’s motorway construction to save for the UK. He flatted with Paul and Mark Hansen in Pipitea Street, down the road from Keith Holyoake. Hansen drummed with influential folk-rock band Tamburlaine and through them he met Simon Morris and Steve Robinson, then Mammal’s Tony Backhouse, Bill Lake and Rick Bryant. “They were all good, established players and I was just a hack.”

This was rich era of music and sociability for him and at one point he flatted with a clutch of interesting, high-achieving women, including educator-author Robina Smythe, filmmaker Jane Campion, and academic-author Dr Airdre Grant. He was Campion’s first boyfriend and they had a serious relationship until Al moved on. “I really loved Jane and was part of their family – it was on that level – so it was quite shocking to everyone when it all came to a painful, horrible end.”

He caught as many international acts as he could, but many of his friends were at Victoria University and persuaded him to go, too, so he did and graduated in geography and arts. In the meantime his music input was growing.

“Simon and I wrote a song for TV talent show Studio One for bands and songwriters. We recorded it, entered under the name of our schoolteacher flatmate, because it sounded better than ours, and called it ‘Boom, Boom’. It was like everything on the radio – ‘Knock Three Times’ or ‘Congratulations’. It was accepted and Desna Sisarich sang it, but the three judges all rubbished it.”

In those days Tamburlaine’s vocalist-guitarist Steve Robinson had a day job with Armstrong & Springhall, which sold and serviced typewriters. Robinson was touring more with the band and proposed job-sharing with Al. The A&S bosses accepted, which freed up Robinson and meant Al could, with time management, work four-hour days but earn eight-hour wages.

Between deliveries, he and then-girlfriend Jill Palethorpe would drive around junk shops buying 45s. This little side gig made him realise how much he liked the ethos of junk shops. “You can be whoever you want to be. It’s an ideal job.”

Running a junk shop, “You can be whoever you want to be. It’s an ideal job.”

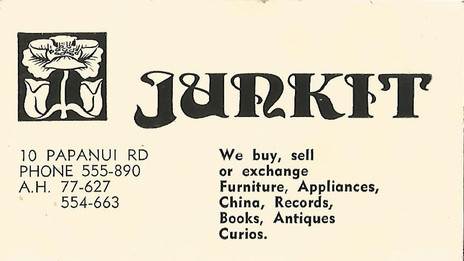

The two left Wellington a few months later and drove to Christchurch in the van Al bought from A&S. Still planning to travel, they were injected and passported for the hippie trail to London before fate took hold. Al met a man with a plan. John O’Brien, who had worked for Phil Warren and Trevor Spitz and whom Al knew already, talked to him about opening a junk shop without needing capital.

“You’d drop posters in people’s letterboxes that say, ‘We’ll take away your unwanted things, clean out your garage, recycle, blah blah blah, and if you want us to do that, put this poster in your window and say yes.’ ”

A few months later they were ready to set up shop. They leased an old house in a prime location on the Papanui Road/Bealey Avene corner opposite the Carlton Hotel, put up a “Junkit” sign to match their catchphrase – “Don’t Dump It, Junkit” – and dressed the shop with items from their rounds. It was late 1976.

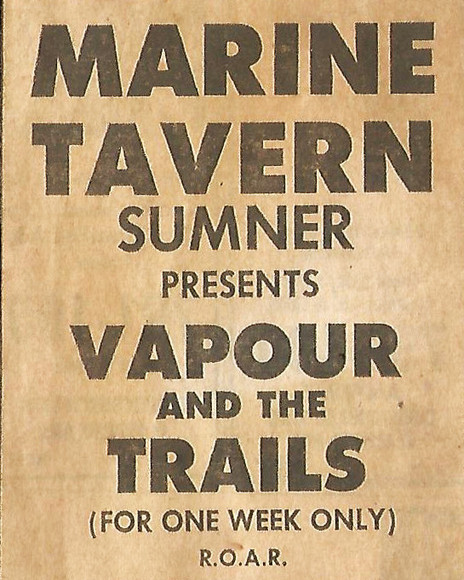

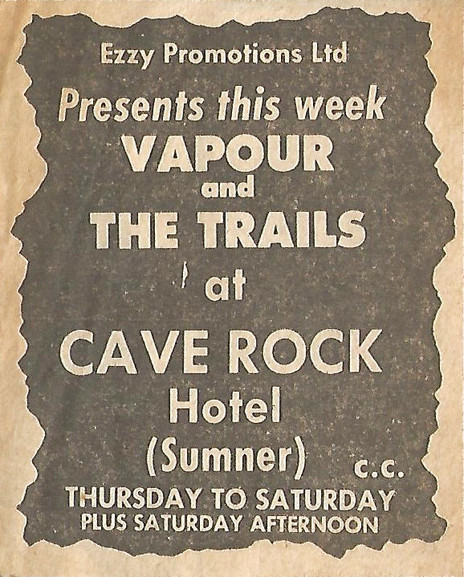

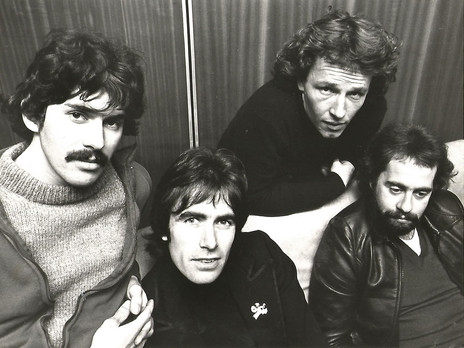

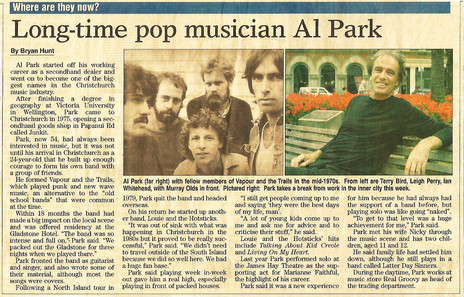

Through the shop his circle of friends was widening. It included innovative mechanical engineer John Britten and musicians Leigh Perry and Ian Whitehead. Al and these two were joined by a drummer and bass player, and this unit became Vapour and the Trails. Their first gig was at a two-night fashion parade organised by Britten, who had designed the wedding dress for the finale.

“The first night it went for so long that we didn’t get to play. We were bummed out, because we were hyped up for it and our eight songs were ready to go. But we played the next night, everyone went nuts and we had to do the whole set again. I had probably the most electric time I’ve ever had in my life.”

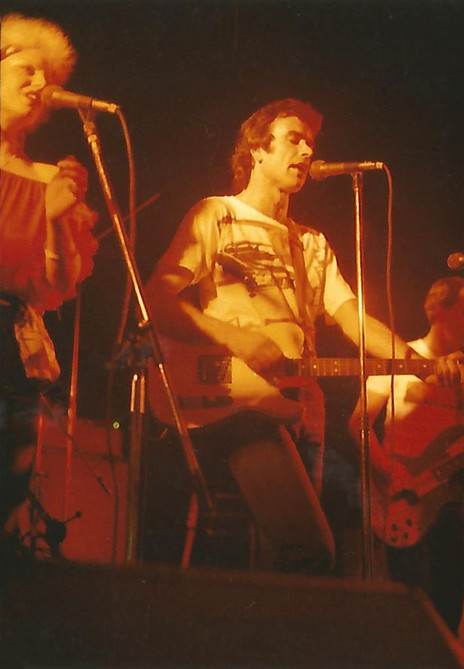

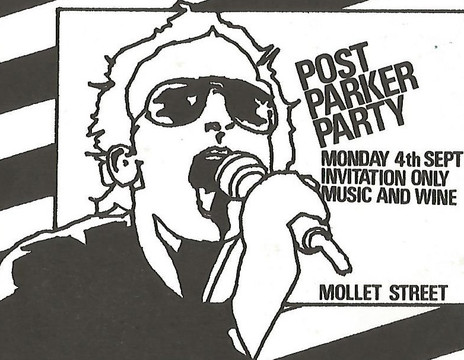

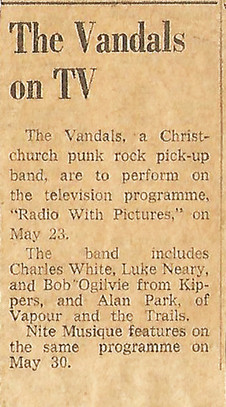

As they added more punk material, their decibel levels were rising. Noise complaints led to them vacating their Arts Centre practice room, so they sourced their own, a large, open floor above a leather shop and burger bar on Mollett Street. They furnished it from Junkit, built a stage and by August 1977 it was good to go. The name Mollett St stuck (instead of a mooted Club de Rox) and although they initially planned it as a private club it became the venue with its punk attitude, party atmosphere, $1 entry, and people lining up to perform.

Mollett Street became the venue with its punk attitude, party atmosphere, $1 entry, and people lining up to perform.

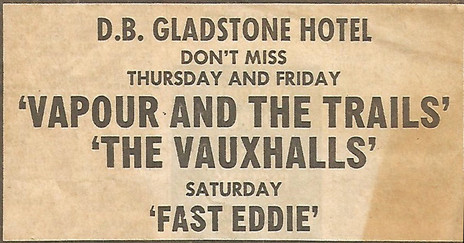

When it closed 18 months later and the Trails needed a gig, they approached the Gladstone on Durham Street, auditioned, got the gig, and attracted 1100 on the first weekend and 1300 the second. In a canny move, Al arranged to do the bookings for when they were away touring. By now, after selling his share of the shop, he had moved into an old cottage in Lyttelton and was living with Brigid Brock, former wife of Warwick Brock from the Band of Hope Jug Band. Artist Bill Hammond, Band of Hope percussionist, lived next door. As well as painting, Hammond was playing his old drumkit, and with Al on his battered guitar and muso friends turning up to jam they had the genesis of Old Denis.

This band was named after OD logos they kept seeing around town. “Bill said, ‘There you go, we’ll call ourselves OD’ and I said, ‘What’s OD mean?’, and he said, ‘Old Denis’. That night we wrote a song called ‘Dirty Old Denis’ and recorded it with Simon [Morris], who was down doing a TV course. He started playing bass for us, so the band could be just me and Bill or sometimes six people, and we were playing down at the British [Lyttelton’s historic, colourful portside pub].”

Al was still itching to go overseas and in 1981 headed to Los Angeles with no particular plans except to experience the music scene. He returned the same year, keen to form a band reflecting what he’d heard: “Kid Creole and the Coconuts, Grandmaster Flash, the Blasters, LA soul, R&B and stuff out of New York. And heaps of people in LA were Van Morrison and Bruce Springsteen-influenced.”

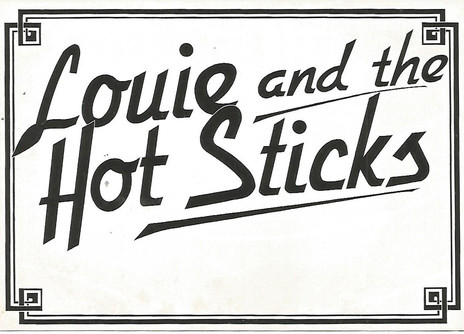

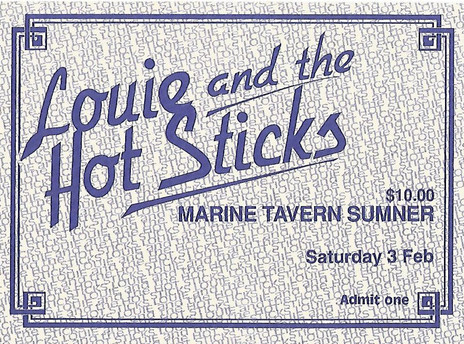

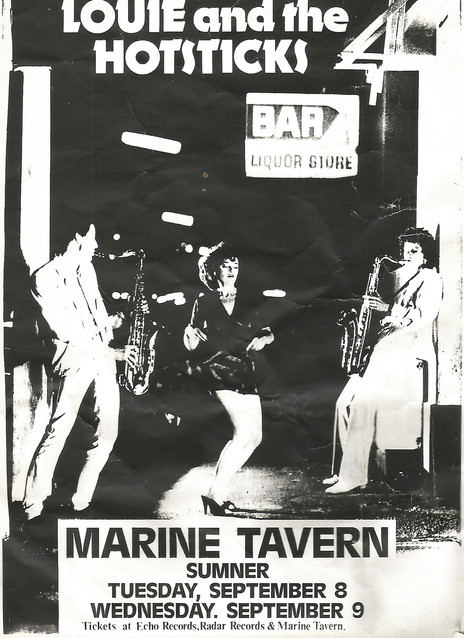

Louie and the Hotsticks was born and venues rocked from the get-go with Al out front, Wayne Jamieson on bass, Leigh Perry guitar, drummer Ronnie Robertson, Danny Wilson on sax and Paul Parkhouse on vocals, harmonica and occasional sax. “Not quite what I had in mind, but it had a real American R&B feel.”

Peter Stephen, now a well-known luthier specialising in double basses and acoustic guitars (Anika Moa plays one of his), was sound engineer and they were back at the by-then skinhead-free Gladstone. As this gig ended and various personnel left, Al and Wayne Jamieson were joined by singer Helen Mulholland, drummer Murray Fisher, and Jimmy Walmsley on guitar. When a Sandridge residency came up they auditioned and expected to get the gig, but management had chosen Friar Tuck instead. “I’d seen what we’d done in two weeks for his bar and couldn’t believe he was telling me that. It was quite a blow to us.”

Instead, they stepped into the gap Friar Tuck had left at the Marine Tavern, took their following with them and at $3 on the door were drawing decent, steady incomes. Danny Wilson had returned on sax with Wayne Beecroft on drums. “That’s when the band really kicked in and we had the sound I’d always wanted.”

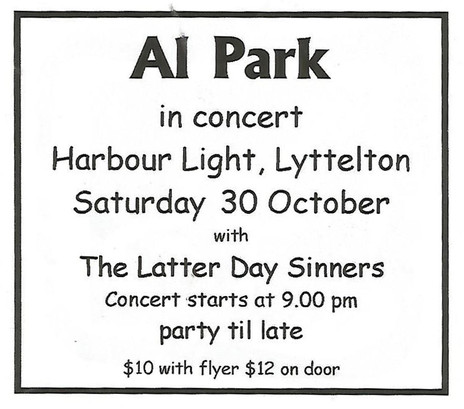

The Hotsticks lasted until the mid-1980s, and when they had one-night revivals at the Ferry Alehouse in 2014 and 2016, hundreds turned up in tribute. After the Hotsticks came Big Elvis (1986), the Red Hot Blues Band playing old R&B, Helen and the Hound Dogs, then party band the Latter Day Sinners.

Between times Echo Records’ Darryl Calcott mentioned Echo needed someone for its new High Street premises. Would Al be interested? Al agreed and was soon managing the second-hand section, for which he was supremely suited with his wide circle of acquaintances and insider’s knowledge of rare releases. He worked there by day and was playing music at night, and around this time, 1987, met Nicky McNab, who became his wife. Separated now, but still friends, they have two adult children, AJ and Ksenya.

“Echo suited me. I was paid well and they looked after me. I was the first guy to have maternity leave and I never worked weekends and public holidays.”

“Echo Records suited me. I was paid well and they looked after me.”

The year 2006 ushered in another major change when Al opened Al’s Bar in Dundas Street. This became a major slot on touring schedules for local and international acts (among them Lloyd Cole, the Stranglers’ Hugh Cornwall, Justin Townes-Earle, Melvins) and was well patronised until the quakes of 2010-11 closed it down. Much to Al’s chagrin and tireless lobbying, it would never reopen.

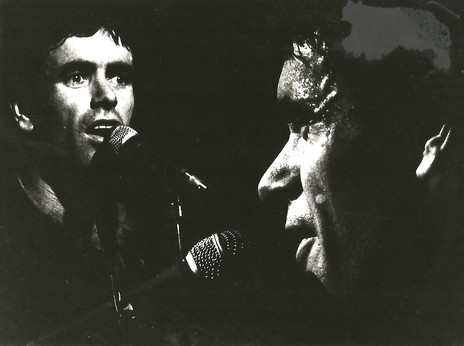

These days Al is as busy as ever, promoting touring acts, playing solo and in numerous line-ups (Park/Hattaway, Runaround Sue, Al and Elmore, Al P and His Pals), and enjoying being at the heart of Lyttelton’s social life and music revival. And ever since the making of Better Already, he has been buzzing: “The show at Blue Smoke was a sell-out and they loved everyone, but it was so cool to see Janice [Gray] on stage. When she walked in, the 300-odd people there shouted with love. She’s 77 years of age and there on the stage she was just givin’ it!

“The best thing about this is I’ve always been collaborative. I’m happy to have been able to share with so many amazing people, and to have them sing my songs and really like them. I feel I’ve been such a small part of the album. I think there’s some really good songs and the people deserve a lot of recognition for it.”

Adam McGrath, who has an abiding affection for Al, wrote this piece in undertheradar.co.nz for the album launch: “He’s our friend, our brother, our anchor, our father, our lodestone, our voice of reason, our bullshit detector, our what to do and our what not do to, our supporter. He’s a deep real influence and we are grateful and this is our tribute.”

--

Read: Al Park talks venues, music, gigs

Read: Al Park on Christchurch skinheads, 1980s