Saunders grew up in the dark landscape under the mountain in southern Taranaki, spending his first 10 years in the small settlements of Mahoe and Awatuna, west of Stratford. On the radio and the family’s 78s, he heard Hank Snow and Hank Williams, the pop music of rural New Zealand in the mid-1950s. From early childhood, he amused himself by singing. His parents Robin and Valerie didn’t play instruments, but he remembers an innate musicality that he described in a 2010 piece for the New Zealand Music Commission.

There was a dark beauty to the Taranaki of his childhood, living among people who didn’t say much and didn’t seem to need to.

“They had a great love of the land and seasons, which made a sort of poetry of its own. My mother would usually have the radio on, a lot of which was the pop of the time, but I was really captured by the odd song that would somehow be an outsider. Songs that seemed to come from another older world; dark landscapes of men who had fallen outside the law, been driven mad by love, greed, or both, and had ended up being hunted, or on the gallows. Songs such as ‘Tom Dooley’, ‘El Paso’, or ‘Frankie and Johnny’, or like when I first heard Rolf Harris singing ‘Sun Arise’ – a picture of a mysterious people in a vast and sunburnt land somewhere over the sea. These pictures seemed to fit the dark beauty of Taranaki where we lived, among people who didn’t say much and didn’t seem to need to.”

When he was 10, the family moved south to Canterbury where his father ran the Lincoln College farm. This was his introduction to life beyond the mountain’s shadow. There was more diversity, it seemed like “people from all parts of the world were there.”

Saunders began attending student dances where the bands played Shadows and Ventures’ instrumentals; music became his main interest. His father recognised this and bought him a Hofner guitar and paid for lessons. “I had always sung, but this was something to sing with. I heard Lonnie Donegan singing ‘Rock Island Line’ and remember thinking this is a track I would like to be on. The train ran right through our farm so all the imagery seemed to fit. I sang songs that were simple and strong like ‘If I Had A Hammer’. The meaning or history of them didn’t even occur to me at the time.”

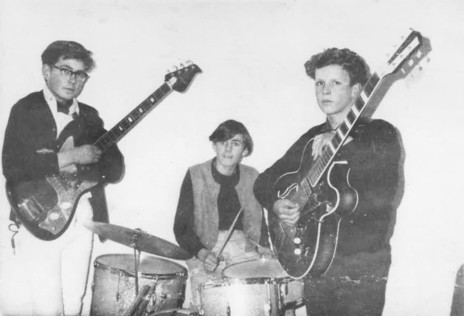

In his early teens, he began playing in school bands. The first song that he can recall singing in public was ‘Greenback Dollar’, a 1963 hit for the Kingston Trio, written by Hoyt Axton and Ken Ramsey. Then the airwaves began to crackle with a new sound. “One day out of the radio comes four chaps singing ‘Love Me Do’ with a harmonica. The world was about to change and music was about to be the lightning rod … A firestorm had blown through the front door and fear had left by the back. Nobody was quite sure what is was, where it was going, or even if it was any good. The only thing we knew for sure was that there was no turning back.”

Music became a “life rope” while at Hillmorton High: it meant you could attach yourself to like-minded people. Among them were friends who had discovered the early records by Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones, and ventured further back to Muddy Waters. These were performers who seemed to live “on the dark side a bit – which I liked.” Soon there were other singers, whose voices “sounded like they were coming out of the center of the earth”.

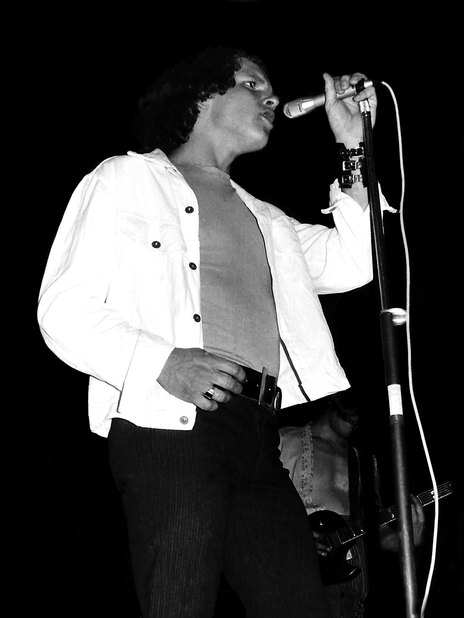

Hearing soul men such as Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett, in 1966 Saunders formed Anarchy, an R&B band, though he reflects that a 15 year-old boy singing heavy songs such as lyric with the heavy timbre of Redding’s ‘Your One and Only Man’ or Waters’s ‘Mannish Boy’ “would probably sound a bit comical”.

The CHRISTCHURCH underground music scene in was flourishing; it seemed like bands “sprung up all over town”.

The underground music scene in Christchurch was flourishing; it seemed like bands “sprung up all over town”. For Saunders, the kings of this scene was the resident band at the Stage Door Club. “Chants R&B played a fearless, white-hot brand of R&B soul and blues. They had what any great band has, in that they could take anything and make it their own. Their counterparts in the north would have been The Underdogs, or maybe The La De Da’s, but the Chants had a heat about them that shook the halls of Anglican Christchurch: a great blueprint for a schoolboy wanting to put a band together.”

His parents noticed the effect the music was having on their teenager. He remembers that one summer, he was working with his father Robin, weeding; his dad went quiet before saying, “Why don’t you forget about everything and just follow the music?”

It was a pivotal moment for Saunders: “With that little handful of words it was like someone had opened a door in a brick wall. A door I had imagined was there, but hadn’t been quite sure – until that moment.”

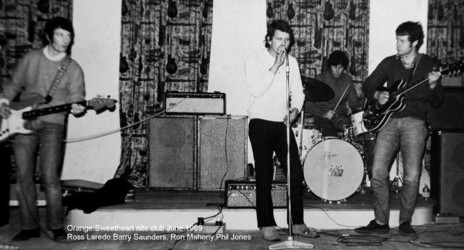

He left school, got a job at the railways and formed a new group: The Orange. Mostly they played R&B dancefloor fillers such as ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ and ‘Smoke Stack Lightning’, plus songs by The Doors. The Orange was offered a residency at The Scene, a club run by Trevor Spitz, “on the condition that we cleaned ourselves up a bit and played some more accessible material. This was a different league. We were getting paid and playing to good crowds. The fact that we had grown overnight from a blues band with wailing harmonica and endless guitar solos, into a pop band, didn’t seem to be worrying anybody.”

There were dances and clubs to play, and a living to be made from music. At the Scene they were required to play two nights a week and on Sunday afternoons. Pubs closed at 6.00pm, and liquor licensing was strict; the dance clubs and halls were all dry. In this scene, the band thrived.

“There was a wild streak around Christchurch then,” Saunders recalled to Trevor Reekie for NZ Musician. “We used to do a great version of Sly and the Family Stone’s ‘I Want To Take You Higher’. A bunch of heavies from Riccarton made us play it three times in a row, which we did: it was the only way we were going to escape with our lives. That sort of thing happened a lot back then.”

In the 1960s “New Zealand wasn’t connected the way it is now, so sometimes it was like travelling to another planet.”

The Orange won a battle of the bands competition and played gigs in Dunedin and on the West Coast. For Saunders it was a realisation that “there was a bit more to it than the music and that the bigger picture was a sort of ticket to ride. New Zealand wasn’t connected the way it is now, so sometimes it was like travelling to another planet. I remember us driving over the Kilmog [hill] into Dunedin in our Morris rental van, into the beautiful grey city with smoke coming up from the chimneys! Those sort of images stay with you forever.”

The Orange ran for three years but never recorded. At the time, Wellington was the home of recording in New Zealand and – unlike Chapta and Revival, who made the sea trip to the capital – The Orange never left the South Island.

By 1972 Saunders had begun to think of himself as a musician, “without too much thought for anything else.” In Auckland, he boarded the passenger steamship Australis to try his luck in England. The original Orange singer Richard Burgess was based in London, and got Saunders plenty of live work on the city’s pub circuit, playing bass and guitar and singing.

“London was grey, cold, raining and beautiful. For a young man having grown up in New Zealand with all its connections to Britain, there was a familiarity to nearly everything. It was great! I was very young and the beautiful chaos and madness of an Irish band in London was sort of like being in a washing machine full of alcohol with a bit of music thrown in.”

Saunders signed on as van driver and bass guitarist for a traditional Irish band called Dingle Spike; the music came naturally. “This was like landing somewhere in my past, and it still amazes me how the music was genetically in me from my Northern Irish roots on both sides. The songs fell out of me like they had always been there. Beautiful Irish ballads, angry, sad rebel songs, and sentimental country songs: music that made you thankful to be part of it. I began to see direct connections between the traditional Irish and the country music that I had grown up with by way of my parents’ records, but it was to be a while before I could make this into something of my own.”

Meanwhile, he tried a day job, working inside the music industry at WEA on New Oxford Street, where his manager was the legendary Derek Taylor, formerly publicist of The Beatles. “He was kind of fearless and eccentric … My job was to send out singles to radio. When WEA released Rod Stewart’s ‘Sailing’, John Peel played it and whole country went mad! But I had forgotten to send it out and so for a while no one played it or could get hold of it. The actual words from his management were, ‘We love Kiwi but, he’s gotta go’. So that was a big full stop for me in record land!”

In 1976 Saunders returned to New Zealand, “on maybe a holiday,” and was asked to join Rockinghorse as a replacement for singer Carl Evensen. The band was running out of steam, but for two years carried on; Saunders remembers enjoying a couple of tours and nights performing with the Red Mole theatre group.

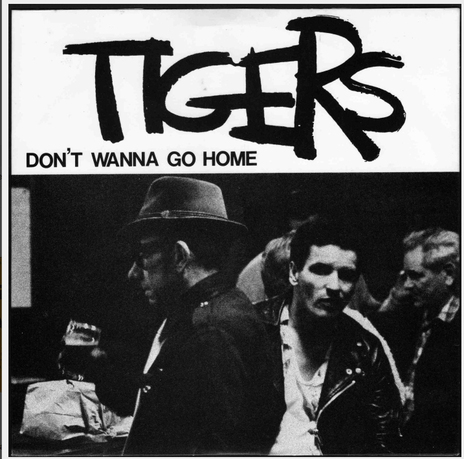

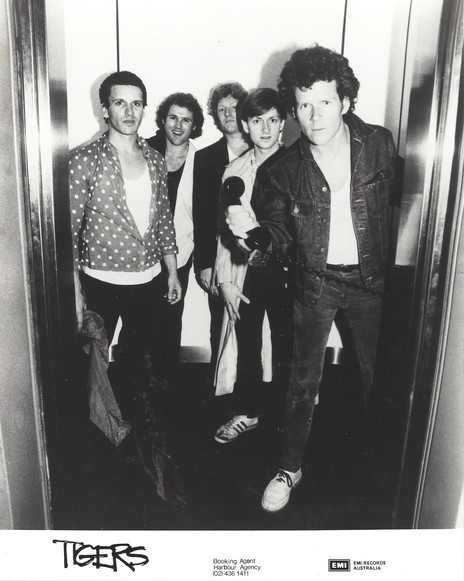

When Rockinghorse split, Saunders stayed in Wellington. With Nick Theobold he began playing at the Woolshed restaurant, with Theobold’s originals gradually entering the setlist of covers. One of these originals was ‘Red Dress’, which they recorded as The Tigers. It reached No.28 in the charts in 1980 and the Tigers became the first local act to be signed to EMI Australia. The guitar-pop toured New Zealand, played a lot of high schools and the 1981 Sweetwaters before crossing the Tasman later that year. Their first gigs were with The Swingers, riding ‘Counting the Beat’. Other tours followed with The Church, Australian Crawl, and Rose Tattoo.

“I had a pocket full of songs, [but] I needed to find a place to work out who and what they were.”

“I went to Sydney with The Tigers and walked straight into the Australian music industry, and all that comes with it: mostly endless touring. We did what seemed like a very big tour with Eric Burdon, but I was very aware that I still hadn’t found my voice, either as a singer or a songwriter. Although I had a pocket full of songs, I needed to find a place to work out who and what they were.”

The Australian touring circuit is well known for endangering the physical and mental health of musicians. The rock’n’roll road lifestyle took its toll on Saunders, and he quit the band late in 1981, hiding out in inner Sydney’s Surry Hills. This recovery time fostered a period of creativity and songwriting. Among the songs to emerge was the Warratahs’ early hit, ‘Maureen’.

Saunders started working with Mick Cocks from Rose Tattoo, playing more country-based material. Unfortunately the demos have been lost to time. But he had found a voice and a sound that suited him and that he felt comfortable with.

By 1984 Saunders was back in Wellington and flatting with Wayne Mason from Rockinghorse days. “Landing back in Wellington with nothing but my clothes and some songs was strangely liberating,” he said in 2010. He had been listening almost exclusively to country records “of the kind that was pop before the country tag came along: Hank Williams, Hank Snow, Jimmie Rodgers, early Elvis, Chuck Berry. The music of my parents and my childhood. It was becoming clear that in order to go forward I needed to grab a handful of the past to take along.”

He felt the urge to form a country-based band using acoustic instruments such as the piano, violin, and drums played with brushes. The Warratahs emerged: a band with traditional instrumentation, that played pop, rock’n’roll and country. A residency downstairs at Wellington’s Cricketers, playing without a cover charge, led to the career Saunders had thus far avoided.

By 1994, after a couple of Warratahs’ albums that Saunders felt didn’t really work, and writing material that wasn’t necessarily right for the band – as well as the touring taking its toll on his health – he took a break from the band. What he didn’t know was that the fatigue was caused by undiagnosed hepatitis C.

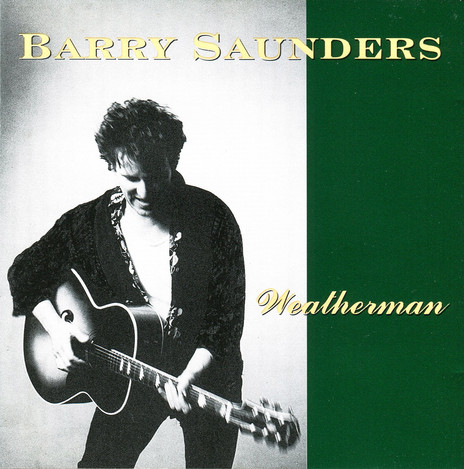

On the ‘Weatherman’ album “the landscapes were darker and more expansive, some quite broken.”

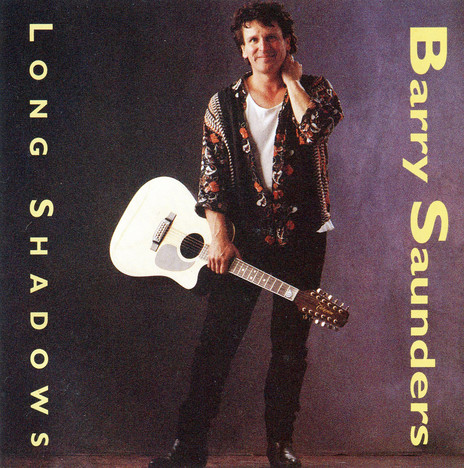

Saunders had released his first solo album, Long Shadows, in 1992; it was an album of 1950s C&W covers, sparsely produced by Ian Morris. In 1995 came Weatherman, which Saunders describes as “a dark little album” that allowed him to separate himself from the band. “Weatherman was my first proper solo album. It was putting a foot on a new land … the landscapes were darker and more expansive, some quite broken.” He went back on the road solo, touring with Sam Hunt in a series of basic show which required them to just walk in, set up and play.

In 1998 Alan Brunton’s Bumper Books published White Man’s Blues, a collection of lyrics by Saunders, who Hunt has called one of New Zealand’s great poets. “Sam is ... very generous,” is Saunders's response.

“I’m very lucky to have a great friendship with Sam. We worked together on those tours and that was a great time, he had his audience and he brought so much to it and we were very lucky. And I have this friend now of 25 years: we speak to each other all the time. Although it’s seldom about poetry and music these days: it’s usually to share recipes or parenting tips. That sort of thing.”

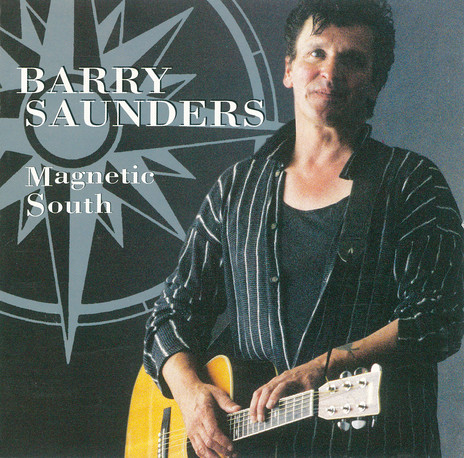

Magnetic South, a third solo album, was recorded with Caroline Easther and pianist Alan Norman in the Polish Refugees’ Hall in Greytown, Wairarapa. It won the New Zealand country album of the year award in 1998, and the trio toured and did a number of international supports, for Joe Cocker, Bob Dylan and Patti Smith, and The Highwaymen.

Missing the instrumentation of the Warratahs, in 1999 Saunders formed another group using that name. It featured original violinist Nik Brown, and the group’s early 90s drummer Mike Knapp (who had been in The Tigers), alongside Norman and veteran bassist Sid Limbert. With Sam Hunt they did the Driving Wheel tour and recorded the album One Of Two Things.

In 2002 Saunders recorded another solo album, Red Morning, working with the Wellington producer David Long, formerly of The Mutton Birds (a suggestion of Saunders’s publisher Chris Gough). The now-diagnosed Hep C meant no more drinking or smoking and, as a result, Saunders was healthier and singing strongly.

The songs ‘Rescue Me’ and ‘Bay of Blue’ from Red Morning were well received by radio and, on the back of its success, Saunders was invited to play at the South By Southwest festival in Austin Texas. “I did a show with Tom House at a little theatre called the Hideout, on 6th Street, not unlike Wellington’s Bats Theatre. I played under a dim, yellow exit sign. It was like a place in a Tennessee Williams film.”

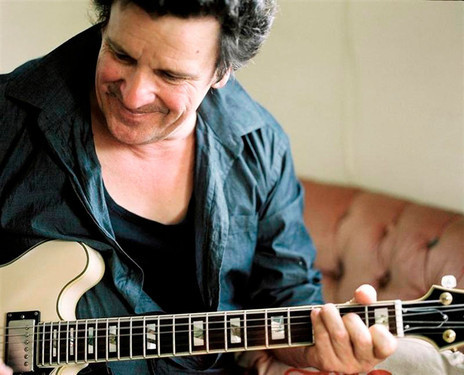

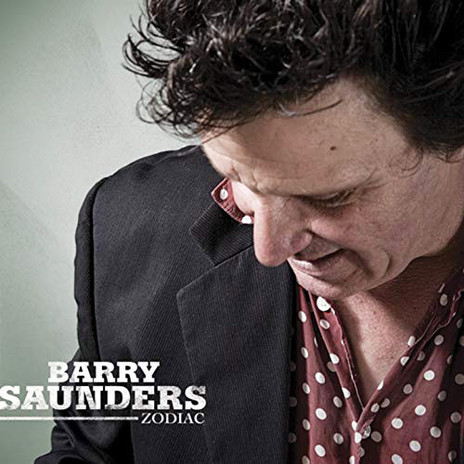

Another solo album, Zodiac, appeared in 2008. Again recorded with David Long, it features Jules Desmond on bass and Craig Terris on drums, resulting in more musically diverse recording. Zodiac included an interpretation of The Phoenix Foundation’s ‘Going Fishing’. “It was a song that got under my skin. Songs do that. I love the lyrics and have turned it into pretty much a country ballad. I played piano for the first time on this album, also played quite a lot of electric guitar.”

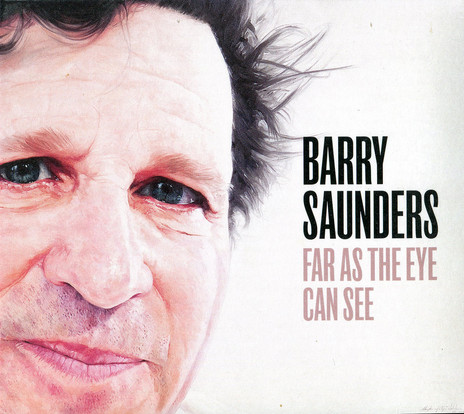

In 2010 Ron Epskamp, curator at Wellington’s Exhibitions Gallery, came up with the idea of asking some prominent New Zealand painters to produce work inspired by songs by Saunders. He sent out the handwritten lyrics to the artists who were tempted. This evolved into a compilation, Far as the Eye Can See, which featured the paintings in the CD booklet. “Since I’ve always seen songs as pictures anyway, it was a very cool thing to do,” said Saunders.

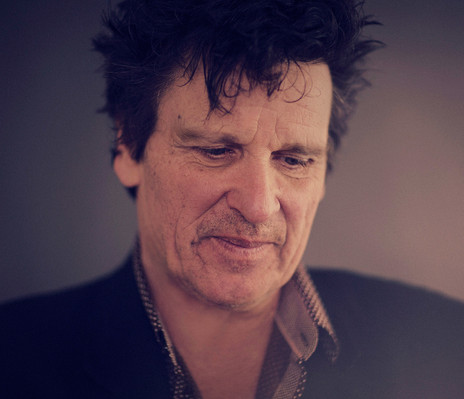

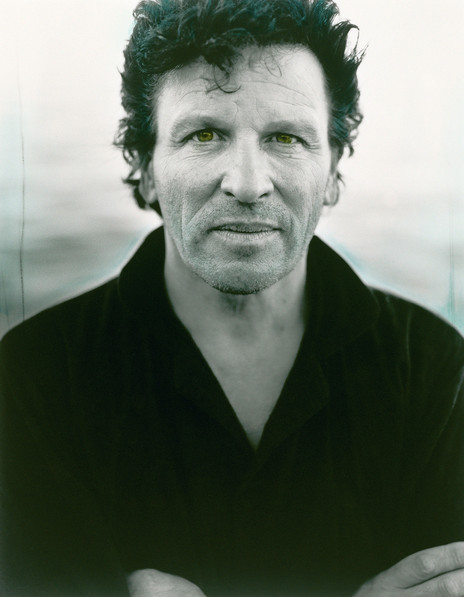

Epskamp found the response from artists approached was uniformly enthusiastic. Saunders was moved as it all came together, telling the Dominion Post, “I turned on the email and saw pictures of my songs on the screen. It was extraordinary.” As well as the portrait of Saunders by Stephen Marty Welch, other works included a surreal photomontage by Bill Kearns (‘Black-eyed Girl’), a landscape for the title song by Kevin Dunkley, and a naked figure floating over Cuba St by Ewan McDougall (‘Rescue Me’).

IN 2011 SAUNDERS WAS Sitting IN A LYTTELTOn CAFÉ WITH musician friends WHEN THE 6.3 EARTHQUAKE HIT.

On 22 February 2011 Saunders was visiting friends in Lyttelton. At 12.21pm he was sitting in a café with Al Park, Delaney Davidson and Marlon Williams when the magnitude 6.3 earthquake hit. “It was an almighty slam like the devil had arrived, a giant had picked it up, the sheer power of it, the streets are going up and down like a ribbon. It made you feel quite insignificant. Nothing and no one will ever be the same. It blew our town and a lot of people’s lives apart. But it also pulled a lot of people together. I became friends with people like Al Park, The Eastern, Delaney, Marlon. It produced a lot of love, music and song.” After the traumatic experience of the earthquake, music provided a cathartic outlet for emotions. Several songs emerged, among them ‘Saraphine’ and ‘Day In A Million’.

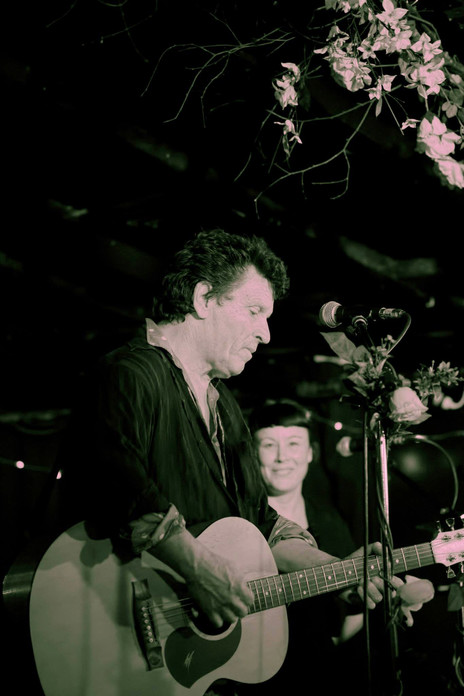

Saunders joined forces with Davidson and Williams – and Tami Neilson – on a six-city church tour in 2015. The sold-out shows brought new country to older fans and older country to new audiences, and the tour became a documentary entitled The New Sound of Country.

The following year Saunders joined the ambitious Last Waltz 40th Anniversary Tour, in which a large ensemble of New Zealand musicians celebrated the music of The Band and their 1976 farewell concert. Guest artists included Garth Hudson, keyboardist of The Band, and the group’s producer John Simon. In Christchurch in the early 1970s, The Band’s albums Stage Fright and Cahoots were especially important for Saunders and his cohorts. “We were huge fans of The Band’s music, so a chance to revisit it in this way was unexpected and special.”

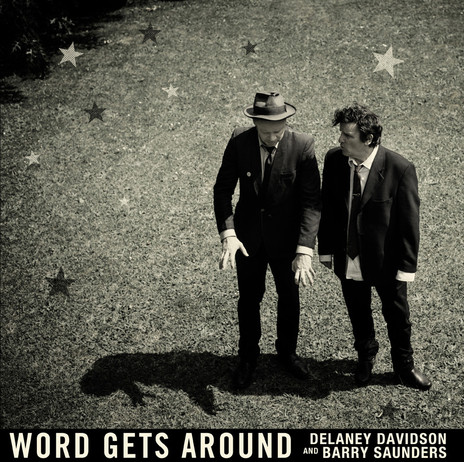

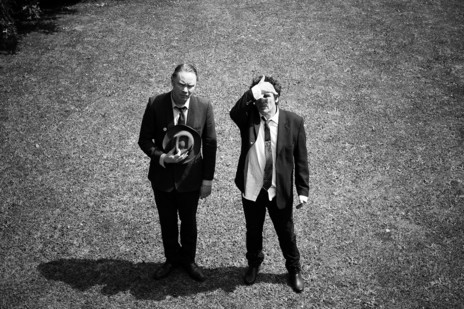

The Last Waltz tour reunited Saunders with Davidson, who – when soundchecking for the New Country church tour – recognised each other’s shared deep influences: The Band and country music. The pair continued working together, combining Davidson’s dark musical landscapes with Saunders’s pictorial, story based lyrics.

Saunders continues performing with The Warratahs. In 2018 the group marked its 30th anniversary with a career-spanning compilation and a national tour.

In April 2019, the musical connection felt by Saunders and Davidson resulted in an album, Word Gets Around. The collaboration, said Saunders, “felt like something that just needed to happen. It felt right ... I was just throwing these words and ideas at Delaney and watching them bounce off his head.” The songs came quickly, said Davidson, “appearing out of the kitchen air and we were grabbing them as fast as we could. [The music] has a realness and truth to it. An immediacy that is hard to find in music. Real songs about real things.”

Davidson’s comment captures the appeal of Saunders’s body of work: real songs about real things.

--

Delaney Davidson and Barry Saunders’s joint album Word Gets Around won the pair the Tui for best country artist at the 2020 New Zealand Music Awards. With the awards ceremony cancelled due to Covid-19, the winners were announced on RNZ’s Music 101. Delaney was called live on air for a spontaneous acceptance speech, where he thanked Saunders for “taking a punt and trying to do something with me which feels like a really fruitful, collaborative relationship”, and happily confirmed that there is more to come from the duo.

--

Read more: Barry Saunders, South Into Winter, 1998