AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

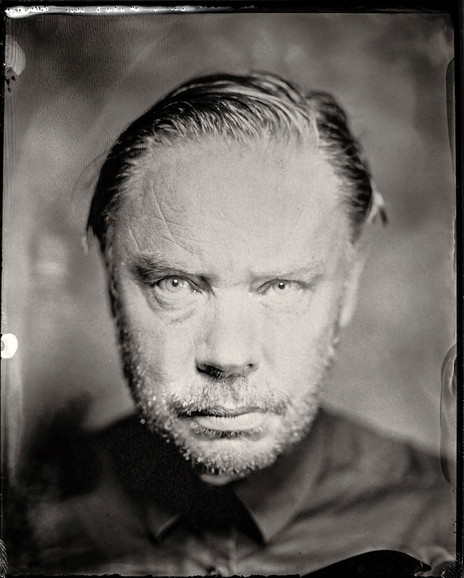

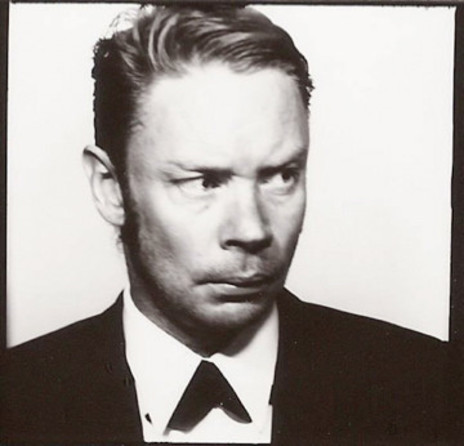

Delaney Davidson

Delaney Davidson is all these things and more. He has been a recipient of an Arts Foundation Laureate and is a three-time winner of the APRA Best Country Music Song Award. He has starred in films, performed in plays and collaborated with many of the country’s best-known musical figures: Neil Finn, Tami Neilson, Barry Saunders and Marlon Williams, among others. And yet he remains a mercurial figure: artistically indefinable, forever in motion. As the bio says, “part man, part wheel.”

Davidson’s journey began in Christchurch, by the banks of the Heathcote River. As a child he took lessons in piano and cello, learned recorder at school, and some violin. His father’s record collection introduced him to 1960s and 70s rock – Stones, Kinks, Bowie – as well as the Chicago blues of the Chess label. “He took me to a lot of music when I was young,” he says of his dad. “The Rolling Stones when I was two months old, Lou Reed when I was four. Sonny Terry when he came out.”

He would also take the young Delaney to hear orchestral performances of classical music.

Delaney had artistic impulses of his own. “I remember I was six or seven, sitting at the piano and looking at the bookshelf and seeing the spines of all these books and making songs up about these books – and it was always down the bottom end of the piano, the dark end – and freaking myself out. I’d eventually have to leave the room because the piano was winding me up so much.”

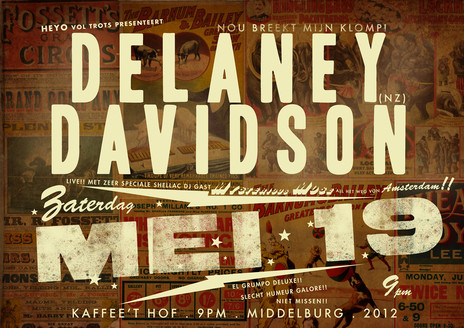

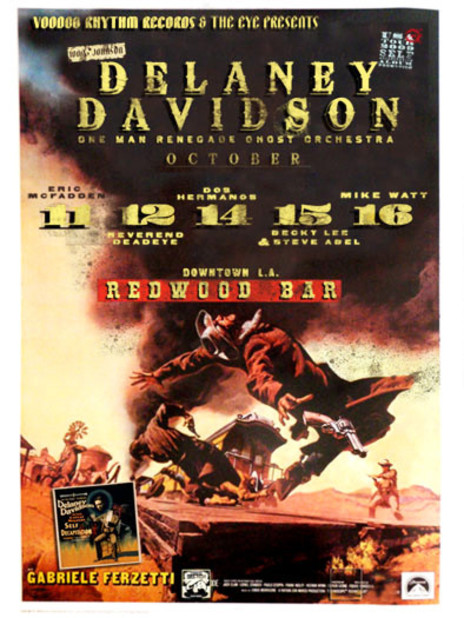

In his mid-teens he played guitar in punk groups around Christchurch. In 1989, age nineteen, he followed his father to Melbourne where he continued to tinker with guitar and drums, but for several years focused mostly on visual arts, “sketching, printmaking, mezzotint, engraving on zinc plates, oil painting”. A visual aesthetic remains a potent part of his work today, with self-designed posters, album sleeves and stage sets.

By his mid-twenties he had married and moved to Switzerland. Here he fell in with a local dark folk band The Dead Brothers. “I recorded two albums with them. One was a bunch of songs we all wrote and the other was music for a radio play. We also did the soundtrack for a movie on Herbert Hoffman, one of the original tattoo artists from Hamburg, who had kept tattooing alive through the time of the Third Reich when if you had a tattoo or were homosexual, you’d be killed.”

The Dead Brothers were experimental in both their music and performance style. “At the end of the show we’d get off stage and perform in the audience. I remember one show, I was doing a solo dragging an ashtray across a table and it was making this strange squeaking noise. People were so tuned into what we were doing that you could get away with stuff like that.”

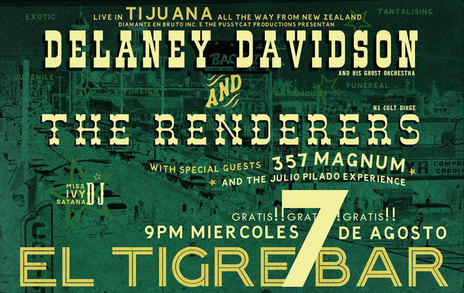

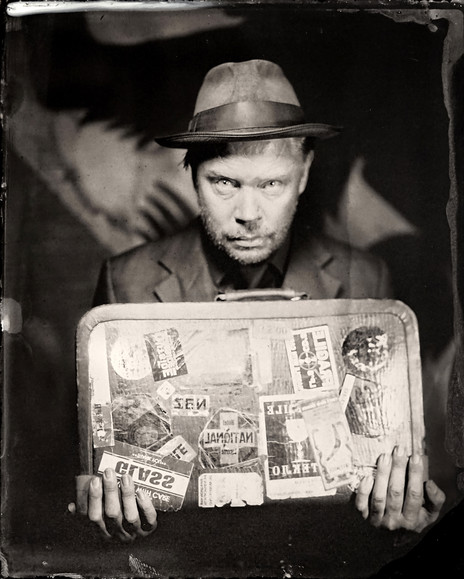

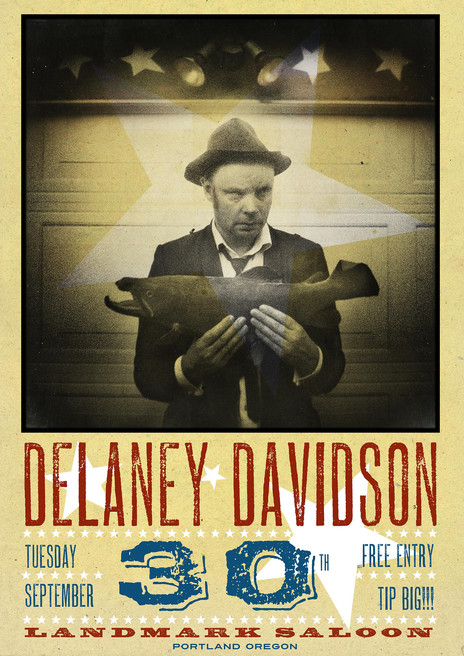

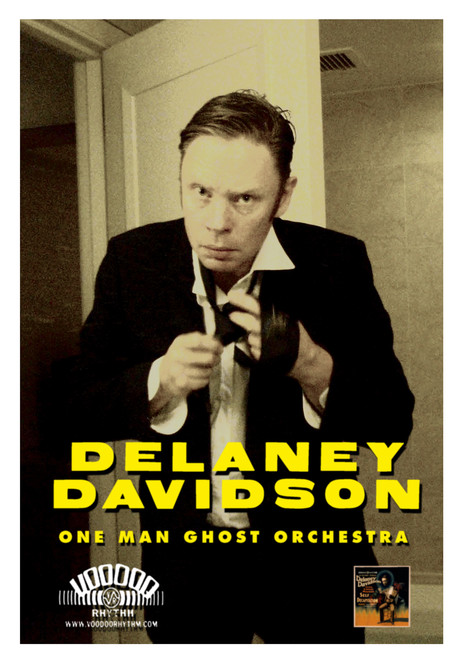

With just his guitar, voice and a loop pedal, Delaney developed his One-Man Ghost Orchestra and the persona of the minstrel-salesman.

The more the group played, the bolder they became. “We were so familiar with the music that we got to one gig and there was a piano there, and the guitarist said, ‘Oh I’m going to play the piano tonight’ and everyone just had to adjust. So it had this real freedom to it.”

After three years with The Dead Brothers, the group “sort of combusted”. The momentum Delaney had gained over that time propelled him into the solo career he has maintained ever since.

“I always look at that like it was my tertiary education. Here’s your three years touring Europe and recording with you guys, and now I’m off.”

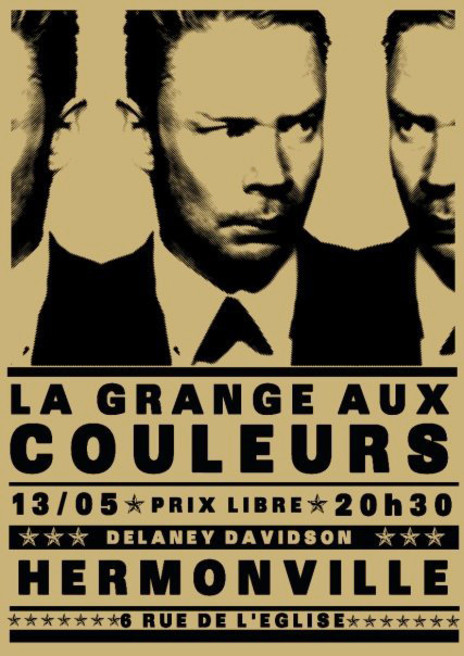

With just his guitar, voice and a loop pedal, Delaney developed his One-Man Ghost Orchestra and the persona of the minstrel-salesman – guitar in one hand, suitcase in the other – began to take shape. At first he performed solo around Bern, Switzerland, where he was living. Soon he began taking his one-man show on the road.

“It was really spur-of-the-moment, living in the present, and following this life wherever it took me. And being that free and open led to a lot of possibilities.”

One night in Bern he opened for British garage-rock original Holly Golightly. They hit it off and by the following week they were touring together in the UK. Later they toured the United States, covering some 25,000 miles together.

On another occasion he opened for Pat MacDonald of American post-punk hitmakers Timbuk 3 (‘The Future’s So Bright I Gotta Wear Shades’). “I said, ‘Would you want to swap a CD for a CD?’ He was uninterested in that idea but I sort of conned him into it, and he said okay. Then I said, ‘I don’t actually have a CD yet but I’ll send you one when I’ve got one’ and he was even more unimpressed with that! But I eventually sent him a CD and he really responded to it. He was like ‘What the fuck is this?!’ He played it a lot at his soundchecks and had people coming up and saying ‘What is that?’”

When Davidson went to the US with Holly Golightly, McDonald drove two hours from his home in Wisconsin to hear him. McDonald invited him to participate in The Steel Bridge Songfest, an annual collaborative songwriting workshop launched in 2006 as a grassroots campaign to save and restore an historic bridge. Handpicked participants had included the likes of Jackson Browne, Louise Goffin and members of the Violent Femmes.

“He’d bought a hotel at Sturgeon Bay and it would be full of musicians. You’d spin the bottle every night and get a team of three people, write a song, and when you were finished you’d tell the studio coordinator and he’d write it on his list and eventually he’d come and say ‘You’re up now.’

“All the songs you wrote had to be about the bridge. Some were from the point of view of a seagull, others might be from the bridge itself, others were about people who had crossed over the bridge. It was a brief just to kick it off. You can always find a new angle. So that kicked me off on the collaborative thing. Decision-making is so much faster with two brains.”

Meanwhile Delaney continued his solo peregrinations around Europe, usually by train. “I would do compilations I’d make up for each gig. I’d get to a town, go to the print shop and get a whole lot of covers I’d designed on the train printed. I’d be burning CDs while I was soundchecking, put those together and sell them at the show. So they were always changing, these weird compilation albums I’d put out.”

Back in New Zealand, Dylan Herkes of Wellington-based indie label Stink Magnetic was becoming aware of Delaney Davidson’s existence. A longtime fan of the Bern-based Voodoo Rhythm label, which had released the Dead Brothers albums, Herkes thought he detected a New Zealand accent in a promotional film. Through Voodoo Rhythm founder Reverend Beatman, he made contact with Delaney. After a visit to Switzerland, Herkes offered to put out an album of his solo material. Delaney gave him the pick of the assorted lo-fi recordings he had been distributing on his homemade discs, and the result was Rough Diamond, the first of his official releases.

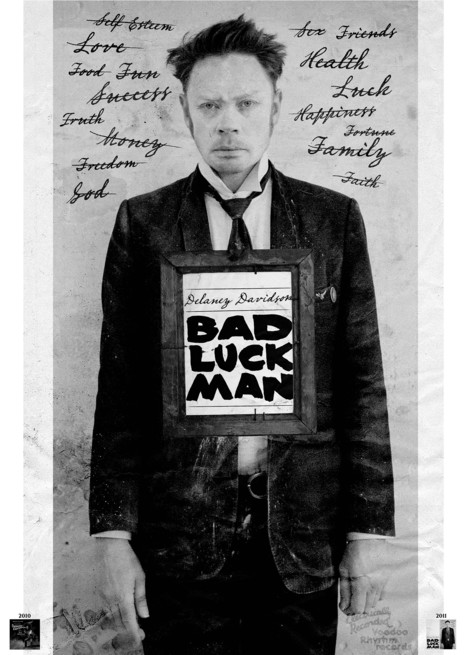

Between 2007 and 2011 Delaney released a further three albums: Ghost Songs (for the French label, Casbah), Self Decapitation and Bad Luck Man (for Voodoo Rhythm.)

He also extended his touring circuit to include annual trips back to New Zealand. For a few years he would spend three months in New Zealand, the remaining touring Europe and the USA. Then the balance began to shift, until he was spending equal, if not more, time in New Zealand.

He would stay with his mother at Governor’s Bay in Christchurch. It was during these visits that he became involved with an alternative music community with strong folk and country roots that was starting to form around Christchurch and Lyttelton. An old school friend introduced him to singer-guitarist Adam McGrath.

“Adam McGrath will always say I got The Eastern together because I had this friend, Jess Shanks, and said to Adam, ‘You two should get together because Jess is wanting to join a band and has just bought a banjo’. And they ended up hitting it off pretty fucking well.”

The same friend who had introduced him to McGrath told him about a young aspiring singer from Lyttelton. “I remember him saying, ‘You should meet this guy, he works at the dairy, he’s a kind of a young dude, wears a cowboy hat. Whenever we go in the dairy he’s always playing Townes Van Zandt, you’d probably get on really well’, and I was kinda like, ‘yeah, dunno …’”

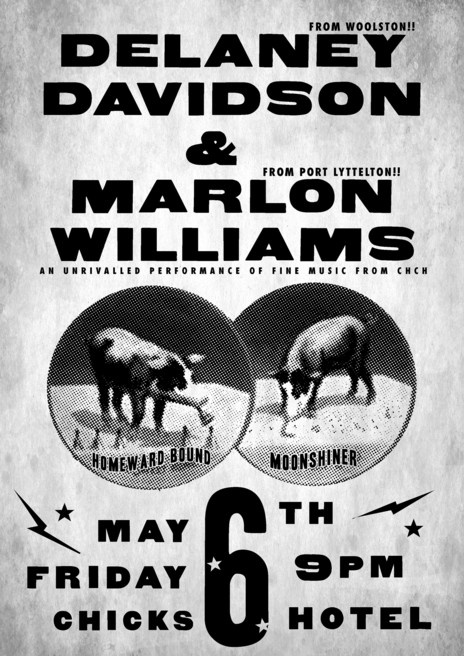

One night Delaney turned up at the Wunderbar in Lyttelton, where he had been booked to play by McGrath, only to find the singer from the dairy also arriving with his guitar. His name was Marlon Williams.

Marlon Williams and Delaney Davidson would go on to perform extensively together, and record three albums.

“We’d both been booked to play the same gig. So it was, ‘Well, what songs do you know? Do you know this? That?’ Soon we’ve got a set list of songs and just ended up playing the show together and it was great. Just the synergy of these quite different voices singing John Lennon songs, a lot of country songs, all sorts.”

Marlon Williams and Delaney Davidson would go on to perform extensively together all over the country, as well as recording three albums between 2012 and 2014: Sad But True – The Secret History Of Country Music Songwriting Volumes 1-3.

In February 2011, during planning for the first album with Williams, the Christchurch earthquake struck. Davidson had originally intended to leave that day for Switzerland, but had changed his ticket at the last moment. A few days later, with the city in shock and ruins, he and Williams met Tami Neilson for the first time.

“Tami was on tour and came to play in Lyttelton, but the place she was going to play, the Harbour Light Theatre, wasn’t there anymore. It was a pile of rubble. Marlon and I were going out to Brighton to play in a park for people who wanted to hang out and lift up the bad juju of the earthquake. I said to Tami she should come along.”

Later there was a barbecue, during which Tami mentioned how much she would like to collaborate musically with Davidson and Williams, and the trio agreed to do a show in Auckland together.

Neilson had wanted to sing the country standard ‘Jackson’. “I suggested she learn ‘These Arms Of Mine’ by Otis Redding and ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, ’cause I just remember thinking ‘There’s some other angle you’re missing here, it should be a bit deeper than what you’re going for.’

“That’s what production is. Seeing the side of that person only you can see, and saying ‘I want to show everybody what I can see in this person.’ You’re just the light, trying to light up the parts you can see.”

Davidson went on to produce Neilson’s breakthrough 2014 album Dynamite!, which took the Canadian-born New Zealand-based country singer from the country mainstream to an area where country meets soul and garage rock.

“What I brought to Tami and Marlon is a much more lo-fi, warm approach to sound, rooted in the ’50s or early ’60s, when it was all recorded in good, little rooms live, people playing together. It has a bright warm kind of grit, mastered hot and loud.”

Davidson co-wrote several of the songs on Dynamite!, knocking out three tunes with Neilson in their first afternoon. “She’s great to collaborate with, quick with ideas and reacts really well.” He went on to produce the follow-up, Don’t Be Afraid.

He continued to collaborate with a wide range of artists across a variety of art forms.

In 2016 he toured New Zealand with Mexican/Californian singer Nicole Izobel Garcia as Manos Del Chango. The following year’s itinerary included performing at Roundhead Studios with Neil Finn as part of his live webcast Infinity Sessions; playing the central role in The Christchurch Free Theatre’s production of The Black Rider, the musical written by William Burroughs and Tom Waits; producing the first solo album of former Hello Sailor guitarist Harry Lyon; a solo tour of small New Zealand towns in which he screened his own movies, and the release of Devil In The Parlour, Harley Williams’s documentary about Davidson’s life and work. Film had long been a dimension of Davidson’s art, from his self-directed music videos to a lead role in The Road To Nod, a 2007 noir drama by German filmmaker M A Littler, “about a guy who gets out of jail, tries to go back to life before jail but everything’s changed, winds up witnessing a murder and killing a guy and he’s on the run for the rest of the movie”.

In early 2017 came The Last Waltz tribute concerts, in which he joined organist Garth Hudson, producer John Simon and a handpicked array of New Zealand musicians to mark the 40th anniversary of The Last Waltz, the grand finale of original Americana roots group The Band.

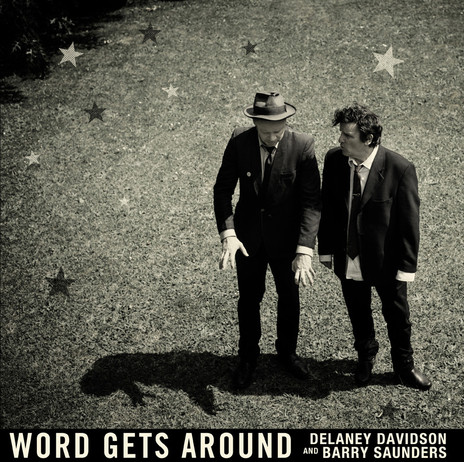

Davidson and Warratahs’ frontman Barry Saunders recognised each other’s shared deep influences

During the shows he worked alongside Warratahs frontman Barry Saunders and they had recognised each other’s shared deep influences, including The Band and country music. Combining Davidson’s dark musical landscapes with Saunders’s pictorial, story based lyrics, they came up with the nine-song collection, Word Gets Around, released in 2019, and the pair subsequently toured together. The collaboration, said Saunders, “felt like something that just needed to happen. It felt right ... I was just throwing these words and ideas at Delaney and watching them bounce off his head.” The songs came quickly, said Davidson, “appearing out of the kitchen air and we were grabbing them as fast as we could. [The music] has a realness and truth to it. An immediacy that is hard to find in music. Real songs about real things.”

Word Gets Around won the pair the Tui for best country artist at the 2020 New Zealand Music Awards. With the awards ceremony cancelled due to Covid-19, the winners were announced on RNZ’s Music 101. Delaney was called live on air for a spontaneous acceptance speech, where he thanked Saunders for “taking a punt and trying to do something with me which feels like a really fruitful, collaborative relationship“, and happily confirmed that there is more to come from the duo.

For his next collaboration he termed up with prolific actor/ musician Troy Kingi, half way through a 10-year project to record an album per year, each one in a different genre. Having already covered rock, reggae, funk and psychedelic soul, the collaboration with Davidson would nominally be Kingi’s folk album, though its dreamy melodies and woozy arrangements leaned towards indie pop and psychedelic-era Beatles. The album was written over an intense four-day period in Wellington in 2020, while Kingi was holding the Matairangi Mahi Toi artist in residence.

Davidson: “Troy wanted these songs to be about the human experience. What is life? What are the things people unite over? The common threads that weave a life together. I started asking him what his thoughts on these times were; fatherhood, love, work, childhood, etcetera. I was trying to get to the essence of what he thought, we always started by talking and stripping it back to get to the core of the message.”

Though the initial concept was that the pair would build the songs around a set of Kingi’s poems, Kingi’s dissatisfaction with his own writing meant Delaney’s role became partly that of a psychoanalyst. Says Kingi: “My poetry wasn’t quite up to scratch and not where I wanted it to be, but we still had to create. So Delaney took it on himself to be somewhat of a shrink, digging deep into my memories, deep into my subconscious to find my own experiences of these different facets which in the end led us to this album Black Sea Golden Ladder.”

Working with Kingi, Delaney had felt “my awareness of te ao Māori starting to wake up.” 2022 saw Delaney back in Wellington, as Massey University’s inaugural artist in residence. The residency gave him time to develop a number of projects, including a fourth album with Marlon Williams and fresh co-writing projects with Anika Moa, Karl Steven and Shayne Carter, all of which remain works in progress.

But the most visible result of his time at Massey was a collaboration with visual artist, actor and activist Tame Iti. Together they produced a striking series of screen printed billboard-style posters proclaiming ‘I Will Not Speak Maori’ – a reference to the written lines Iti had been forced to repeat on the blackboard as punishment for speaking te reo Māori at school in the early 1960s. Not only did the posters appear all over Wellington and in other cities around the motu, but formed the basis of an installation at the Massey campus and an exhibition at the Suite Gallery. Delaney further immersed himself in the visual arts with a residency the following year at the Stoddart Cottage in Ōtautahi Christchurch, during which he produced a series of mixed-media landscape paintings.

2024 saw the release of Out Of My Head, his 10th solo album and sonically richest record yet, spanning lushly orchestrated ballads and fuzztone garage rock. A highlight was ‘Heaven Is Falling’, a gothically inclined duet with Reb Fountain.

When I interviewed him for AudioCulture in 2017, he spoke of how convinced he was in the social importance of the artist’s role. “The earthquake in Christchurch was a big time for that, of seeing the true value of music. All the musicians in that scene really felt they had a purpose. The time we met Tami and played in the park in Christchurch, people weren’t there to play cricket and they weren’t there to chuck a rugby ball around. They wanted to be lifted up and nothing could do that apart from music.”

He had received an Arts Foundation Laureate in 2015, but fantasised about a more formalised role for the “part wandering minstrel, part traveling salesman” character he inhabits. “It’s a hard thing to describe – like an official presence of Delaney Davidson,” he mused. “I’m totally happy to see it as a character. I’ve done quite a few talks at universities and I like the idea that there is some weird shady professorial idea of who this guy is or what his presence could mean. He played at a juke joint in Portland Oregon or a saloon bar in Texas or he lectured at the university. He has these weird hats he keeps changing, this man of a thousand faces idea. [James K] Baxter was a bit like that. Len Lye is another one. A lot of people I admire, that’s what they did, and that’s what I’d like to do as well. You carve out the job you want for yourself.”

And it seems that is exactly what he has done.

--

Delaney Davidson's video interview by Ross Cunningham for AudioCulture can be seen here.

Voodoo Rhythm Records

Lyttelton Records

Squoodge Records

Stink Magnetic

Outside Inside Records

Rough Diamond Inc

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air