AudioCulture

The noisy library of New Zealand music

Te pātaka korihi o ngā puoro o Aotearoa

Trevor Spitz

His Christchurch clubs and skills as a promoter helped get some of New Zealand’s top acts of the day on the road, and his involvement in revitalising music television gave many artists the kind of exposure they could never have otherwise dreamed of.

Spitz helped establish TV3 and held licensing rights to some of the biggest children’s entertainment franchises. He created a Thomas the Tank engine replica based around his ride-on lawn mower and promoted a science and astronomy teaching aid for schools before succumbing to cancer in 2012.

Back in 1957 a Tauranga duo, Mike Horman on piano and Colin Minifie on clarinet, began changing their repertoire from waltzes, foxtrots and old time jazz to embrace the modern songs young people seemed to be attracted to.

In doing so they won themselves a faithful following. When I spoke to Trevor Spitz around 2004, he couldn’t recall how he came to join them. “Maybe they were playing at some church social and I got involved by playing the spoons or something loose like that ... I probably had aspirations to be a drummer.”

Spitz recalled the first time they hooked up as a trio, at a 21st. “We each got a box of chocolates and thought we were made.”

Robin Smith (the older brother of the Rocky Horror Show’s Richard O’Brien) got involved on saxophone. Minifie added another saxophone, extending the scope of the repertoire. With twin saxes they could play a more authentic version of ‘Three Steps To Heaven’ and Billy Vaughan covers.

Saxophone to guitar

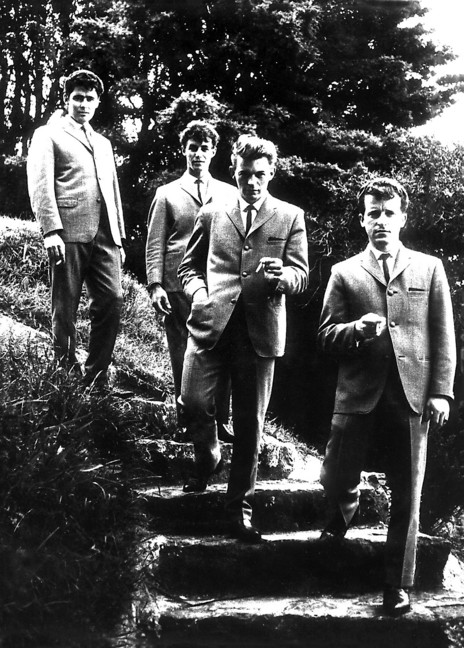

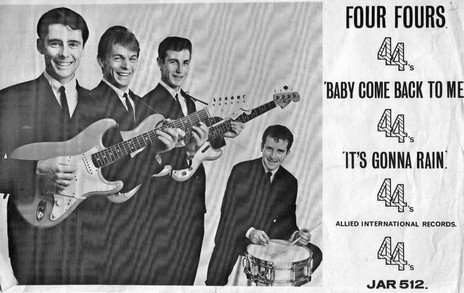

Bill Ward joined on a Commodore lead guitar and vocals in 1959 and the name The Four Fours was adopted. It was his first “real” band. He was a little older than the other members and taught them all to play guitar.

Horman added homemade bass to his skills and the cover songs took a leap forward. The bass, guitar and vocal mic were all amplified through a little green 15-watt amp, with a single 12-inch speaker, made by Spitz.

Bill Haley and the Comets’ ‘Rock Around The Clock’ and the growing influence of Elvis Presley challenged the little unit to shift to more rock and roll, including Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis. The arrival of The Shadows and The Beatles shifted the sound again.

“We had what we believe was the first reverb unit in the country. We made such a show of it. We’d play something without reverb then hit a switch on the floor and a coil of wires on the floor would go twaaang and you’d play the piece again,” said Spitz.

“We were pretty onto it. We even had a couple of young girls join the group doing doo-wops. When syncopated clapping was the in thing I made a clapping machine – a couple of hunks of wood hooked onto a solenoid, which was triggered by my drum pedal. There’s nothing we didn’t have a go at.”

When The Shadows were topping the pops the band had “Hank Marvin glasses” and when The Beatles made it they wore Beatle boots. “We went through all the different phases ... whatever was in vogue at the time. We were very much a pop group. If it was popular we did it or found a way to do it.”

There was very little entertainment in the Bay of Plenty in those days and The Four Fours had a strong fan base.

There was very little entertainment in the Bay of Plenty in those days and The Four Fours had a strong fan base. Trevor Spitz’ parents were St John Ambulance people and let the band use their hall for a dance every Saturday night for two to three years. If you were lucky you even got a cup of tea and a bun and a waltz or foxtrot to keep the older folks happy. For the young people, The Four Fours covered the Top 10. “We’d hear a song on the radio that we liked and then switch stations and see if we could hear it again so we could learn it,” says Bill Ward.

The band ran barn dances with bales of hay around the hall, and theme shows such as Showtime Spectacular at the Town Hall where they invited guest artists. The sound changed again when sax player Colin Minifie left.

(Colin Minifie went on to some success in Japan as a novelty act where he would put a mouthpiece on a variety of vegetables and play them like a musical instrument. He played carrots, a stick of rhubarb, a marrow and even a cabbage.)

Cop adds rhythm

The arrival in 1960 of Dave Hartstone, a former policeman from Auckland, on rhythm guitar and vocals, kept The Four Fours true to their stage name. Soon he and Bill Ward were experimenting with vocal harmonies and original music.

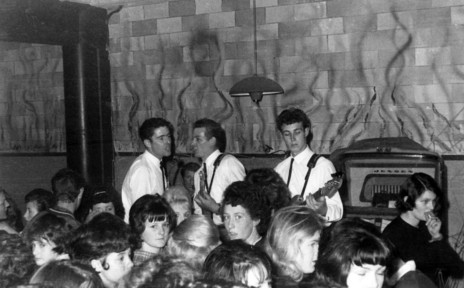

The Four Fours continued to pack out dances at the St Johns Hall and the YMCA in Cameron Rd, Tauranga, and began performing Sunday nights at the Inferno coffee bar, owned by 19-year old Spitz.

“The Inferno was an excellent venue and the only place with live entertainment in the city at the time. Our parents used to think it was a real den of sin – a few of our mates were banned from going there. We used to smuggle in liquor and have a great time,” says Ward.

The band played a few dances beyond their hometown and was beginning to get noticed outside of Tauranga, even coming to the notice of the New Zealand Broadcasting Service (the precursor of the NZBC) which booked them to play their first original song, an instrumental titled ‘Barrow Boy’, on the Happen Inn show.

However, pianist and bass player Mike Horman was leaving. As a joke one of the band members called out to young Frank Hay, who worked behind the counter at the Inferno. “You like music don’t you Frank? ... Can you play bass, Frank?”

Hay admitted his complete lack of musical ability and was further perplexed by an invitation to join the band. He didn’t know what he’d just got himself in for. They conned him into miming the film session in Auckland.

“He actually ended up being a very good bass player once Dave Hartstone and I taught him the keys and the runs,” says Ward.

During a three-month stint in Australia in 1961 the group realised how naïve they must have looked trying to front up against the professionals so they upgraded to better quality Jansen equipment and upped their rehearsals.

Stepping up and back

In November 1963, the band quit their day jobs and headed to Auckland where they met up with entrepreneur Dave Dunningham, who assured them they’d get plenty of work.

Ironically the first job meant travelling back to the Bay of Plenty to play the Christmas season at Le Mount and the Peter Pan at Mt Maunganui. Dunningham had insisted on only hiring Auckland-based acts.

“We arrived in Auckland almost directly after Max Merritt & the Meteors and Ray Columbus and The Invaders had left for Australia. They had been the main groups and left a huge gap. Herma Keil and the Keil Isles and some other good groups were working regularly but there was no one really hot until The Underdogs and Larry’s Rebels came along a year or so later,” says Spitz.

“We stepped straight into Phil Warren’s Monaco nightclub which was the top teenage spot, featuring go-go girls, then headed off to the Platterack – the late night scene where all the people from the strip clubs and the restaurants went after they finished work. They were two totally different crowds but because we were a pop band playing a huge variety of stuff we didn’t have to change our repertoire much.”

Soon The Four Fours were playing seven nights a week and had signed to George Woollers’ Allied International Records. Their first few singles were minor hits but despite their best efforts, recording at Stebbing Studios in Herne Bay, most failed to click with their live audience.

On record they began to sound like a beat band while live they remained a hard working covers group, serving up the songs the fans were familiar with from radio and TV.

Finally they hit with the 1965 instrumental ‘Theme From an Empty Coffee Lounge’, reaching No.1 on the local hit parade.

Finally they hit with the 1965 instrumental ‘Theme From an Empty Coffee Lounge’, reaching No.1 on the local hit parade.

The Ward-Hartstone composition was so fresh when it hit the studio that Hartsone had to whistle the melody line for the band to play along with. It sounded so good they left it in.

“It was pretty amazing for young fellows at that time, doing black and white television and recording in the basement of Stebbing Studios. It was hard work but it was fun because to a large extent you were growing up with your audience,” said Spitz.

Restless for change

The Four Fours were getting restless. Their contemporaries were heading off across the ditch for a shot at the Australian scene but they were determined to take things one step further. The grand vision was to become the first New Zealand group to break into the British scene.

Trevor Spitz, while helping to organise the trip, was divided. He had responsibilities with the Inferno coffee lounge. Over the 18 months the band had been resident in Auckland the cash registers had rung less and less and he began to hear the title of their first hit record echoing in the back of his mind.

Dave Hartstone never got on too well with Spitz, who thought his addition to the band was unnecessary. “Trevor pretty much ran The Four Fours his way, and although it might have been good in the early stages, we needed change,” said Hartstone.

Spitz weighed his options and decided to try and rescue his investment, leaving the band to audition for a replacement.

He was replaced by stand-up drummer Maurice Greer from Palmerston North group The Saints and the rest is history. The hard working unit changed their name to The Human Instinct on the way to the UK, spending 18 months on the circuit before returning home to record six classic New Zealand albums over the next decade.

Spitz didn’t regret his decision to leave The Four Fours. After his coffee bar went belly up, he headed off to relax in the sun in Surfers Paradise and rethink his life.

Then promoter Phil Warren asked him to come back and run the Soundshell in Napier for three weeks. Warren was also keen to start another late-night club in Auckland and Spitz got the job getting the first Mojo’s off the ground with The Mike Walker Trio in residency.

From clubs to television

Warren had also taken over a teenage club called Pride of Place in Christchurch and sent Spitz down for three weeks to manage the venue under the new name The Monaco. Later it was reworked again under the name Aubrey’s, where Ticket formed as the new resident group.

Spitz remained in Christchurch and ran the Caledonian Ballroom where 1000 people would turn up on every Saturday night. “All the guys used to wear a jacket and tie. You wouldn’t get in otherwise.”

He ended up running three other teenage nightclubs: acting as agent for Warren’s Fullers Entertainment Bureau, late night venues Mojos in Christchurch and Dunedin and Adam’s Apple in Christchurch. He was instrumental in helping local acts get established. Among them were Ticket, Craig Scott, Laurie Dee, The Chapta, Dave Kennedy and Link.

In an article for NZ On Screen, Jon Gadsby, David McPhail and Tom Parkinson, in honouring their late colleague and friend Trevor Spitz, explain how his skills in artist management got him involved in television.

In a newspaper advertisement for singer Laurie Herdsman in the Christchurch Press, Spitz made the most of the space by shortening his name to Laurie D; as a compromise Laurie agreed to become Laurie Dee.

In the early 1970s Dee became the lead singer of Beam Unity, whom Spitz convinced TV One producer Kevan Moore to use on several entertainment shows. Beam Unity, featuring Chris Whitehead on drums, Phil Whitehead on guitar, Wally Dunn on bass and Don Mills on keyboard and vocals, eventually became simply Beam. Mills and Phil Whitehead later joined Think.

For Spitz that association with Moore opened the way for further involvement in TV, becoming the South Island talent scout for shows including C’mon. Ray Columbus handled the rest of the North Island.

Serious about comedy

When South Pacific Television (TV2) came on the scene Spitz became talent coordinator for all its shows, including Opportunity Knocks and Telethon. He quickly mastered the entrepreneurship side of TV production, “bringing to the table image awareness, marketing, show business savvy and good soundtracks.”

When A Week Of It hit the screen, Spitz helped arrange the shows and warm up audiences beforehand. As the popularity of the satirical McPhail and Gadsby comedy show grew he helped with live shows and formed a management company to further develop their careers.

“He got hold of us and pretty much completely reorganised us,” said Gadsby. “Spitzy was a great organiser. We’d begun doing regular cabaret seasons at Auckland’s Ace of Clubs and Shoreline, along with John Clarke (Fred Dagg), Billy T and others. With Trevor involved, the returns to us and other artists working those venues ... well let’s just say they increased dramatically. Trevor was a good manager.”

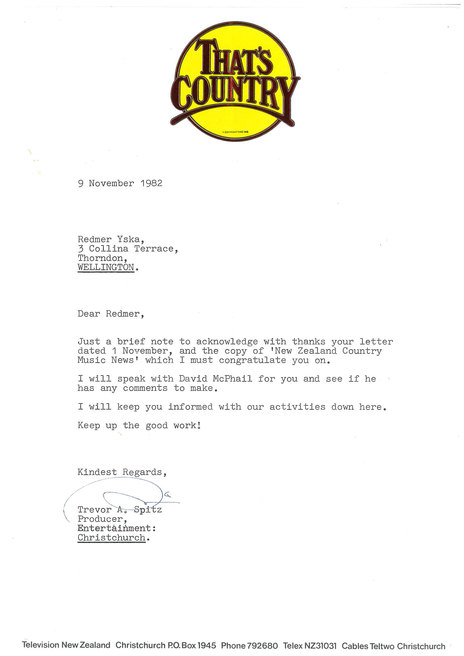

Around the same time it was decided to modernise the ageing country and western TV show A Touch of Country. Its replacement That’s Country featured more modern crossover country and Spitz was brought in the produce alongside David McPhail and John Lye.

Spitz’s contacts within the music industry ensured the first four series featured the best of local and international acts and the show caught the eye of a Nashville cable TV network

Spitz and TVNZ’s Head of Entertainment Tom Parkinson flew to the USA to sign the deal with the Nashville Television Network (NTN) for 44 more episodes, with a guarantee of regular US stars and a licence fee that was greater that the initial show’s entire budget.

With the signing of the US contract, That’s Country had to lift its game in every way. Tensions arose between several of the show's musicians and producers over a perceived conflict of interest, and the resulting dismissal of two artists sparked a scandal.

According to a biography on NZ On Screen by David McPhail, Jon Gadsby and Tom Parkinson, “The public service union, opposition political parties and actor’s equity were all publicising their opinions. Trevor was their main target, due mainly to a perception he was conflicted by being involved in the commercial side of show business (one of Trevor’s star clients, Suzanne Prentice, played regularly on the show).”

Prime Minister Rob Muldoon began a Commission of Enquiry into That’s Country, which lasted for 12 months then – wrote McPhail et al – “applied some wet-bus-ticket slaps on the wrists of various TVNZ executives, for alleged violations of public service codes”.

Groundwork for TV3

Spitz simply got on with his next venture, winning the TV3 warrant for the South Island as part of a consortium bid which was to prove a “poisoned chalice,” thanks to politics, the 1989 stock market crash and infighting between TV3’s non-broadcasting shareholders.

TV3 was eventually forced to go on air as a national broadcaster with Spitz moving to Auckland to work with programmer Kel Geddes, where he created programme imagery and marketing including a contract with Disney.

He personally held the licensing rights for live appearances for Disney, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The Simpsons, Bananas in Pajamas and Thomas the Tank Engine characters. Spitz remained with TV3 for five years.

Having watched the growing popularity of Thomas the Tank Engine, he built a replica around his ride-on mower with three passenger carriages. Dressed up as an engine driver he began working the shopping malls and was an instant hit.

He made money photographing children with Thomas using the photographic equipment he’d purchased to enhance the look of That’s Country.

Spitz sold the Thomas franchise in 2007 and returned to refurbishing his Marlborough Sounds home. He was diagnosed with melanoma in 2010 and after a short reprieve, died 19 March 2012.

--

Sources:

Keith Newman, personal interview with Trevor Spitz, Dave Hartstone and Bill Ward circa 2004-2006.

Some of the details of Trevor Spitz’ television career was gleaned from material provided to NZ On Screen by former colleagues Jon Gadsby, David McPhail and Tom Parkinson.

Visit our sister site

NZ On ScreenMade with funding from

NZ On Air