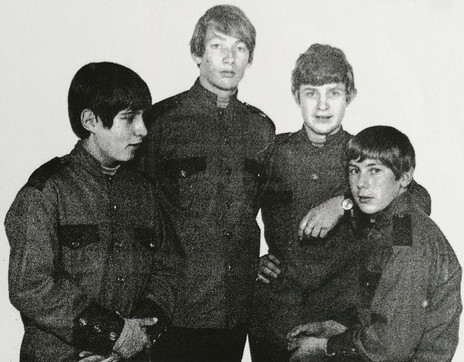

They were encouraged to bigger things than Bible class dances by Tony and Paul’s mother, Mrs Phyllis Rabbett. It started with a fascination for The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and the mid-60s British rock explosion. “Mum was more keen than we were about becoming rock’n’roll stars,” says Tony Rabbett.

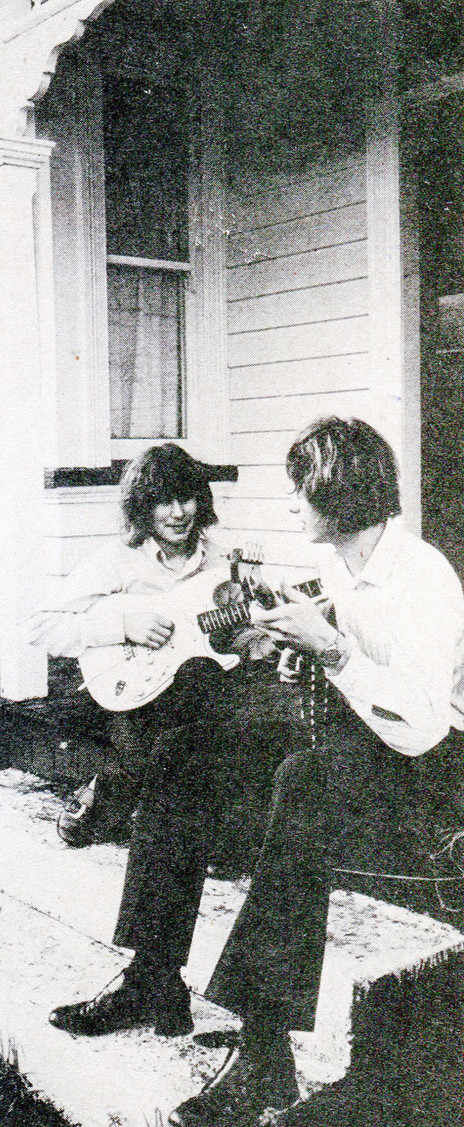

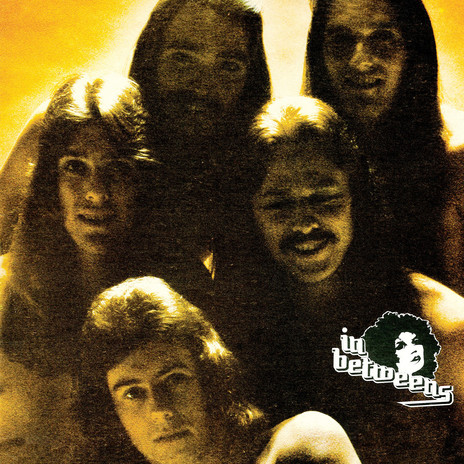

Tony on rhythm guitar and vocals, Paul on drums, and Roland on lead and bass were soon joined by Murray Newey on keyboards. Their name, The Inbetweens, matched their ages – 13-15 years – and came courtesy of Mrs Rabbett, who got them gigs, started their fan club, produced a newsletter and was their biggest fan.

Their father wondered why they weren’t looking to get “a proper job”. “He used to ask ‘what do you think you’ll be doing when your 40?’ We’d say, ‘probably playing in a restaurant somewhere’. Other than the occasional part-time job, I’ve been in the music industry my entire life,” says Tony.

When another school friend, Martin Platt, joined on bass, Tony moved to lead guitar and the gigs kept coming. Mrs Rabbett kept up the marketing and promotions and soon they were rated among the top bands in the South Island.

Battling the bands

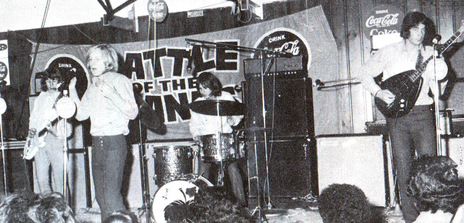

Martin Platt moved on and Roland Farmer moved back to bass. They won the regional finals of Benny Levin’s Battle of the Bands in January 1968 and went to Wellington for the national finals, but were kept from the top spot by The Fourmyula.

The Inbetweens were reliable, they looked the part, and they knew how to draw a crowd at teen gigs. One punter recalls a dance at Alexandra Camp Ground Hall in Central Otago where the band played Beatles and Stones and had the place pumping. As the night wore on they cranked up the amps and management were so annoyed they pulled the plug and kicked them out.

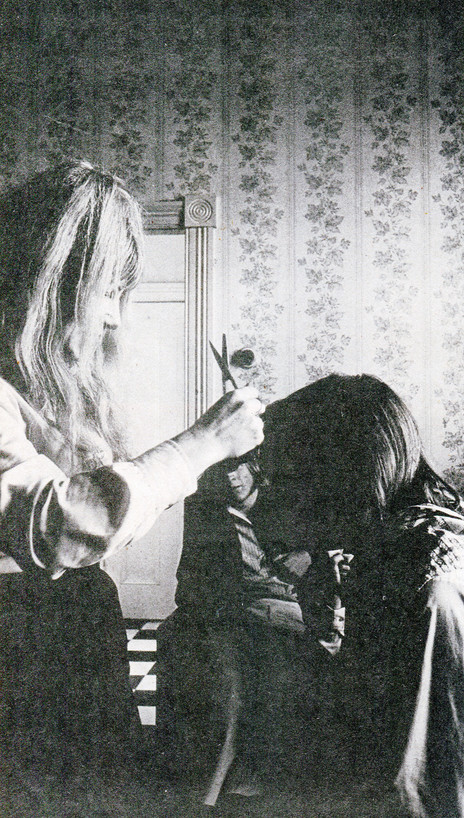

In February 1969 the Listener said The Inbetweens were “winning new fans everywhere they go ... [they] have an exciting sound on stage and with a little more experience they could make a big mark.” Their “thriving fan club” even mailed out locks of their hair. “However, don’t all write at once. The Inbetweens need the hair they have after the last scissor attack.”

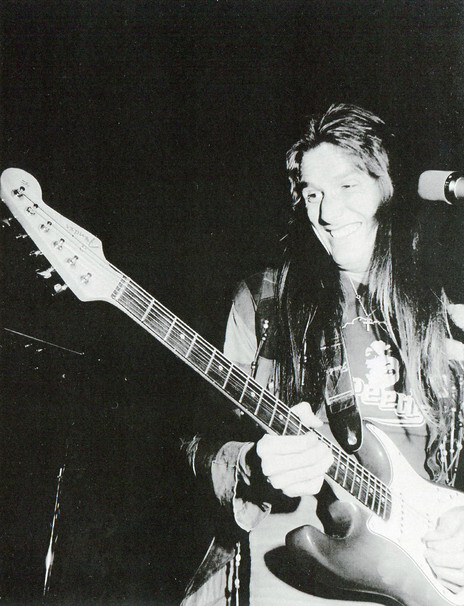

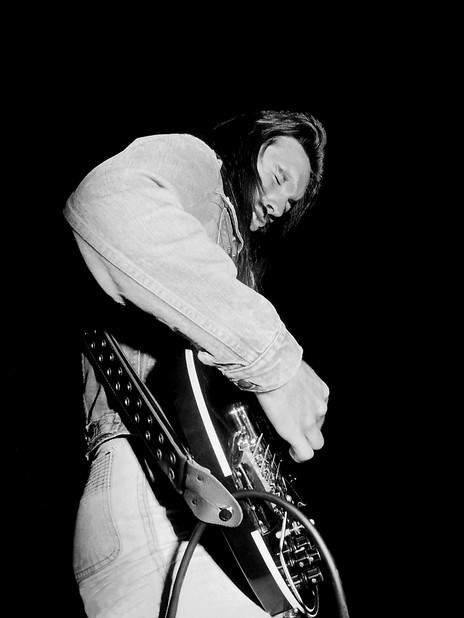

The band played many weekends at Dunedin’s Agricultural Hall, sharing the stage with two other groups. They continued to cherry-pick radio playlists and vinyl albums with Tony spending hours trying to copy Jeff Beck’s work on the 1968 Truth album.

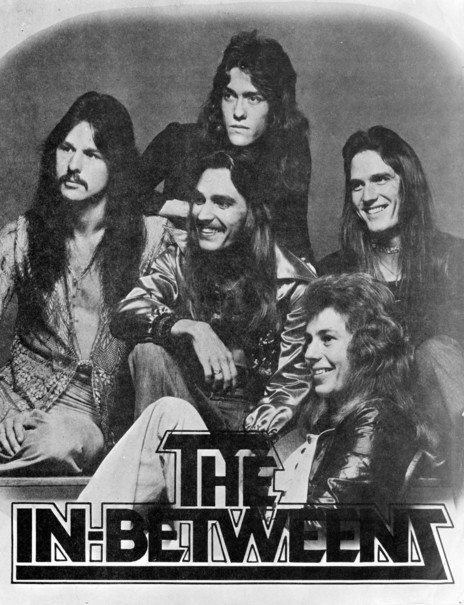

In 1970 The Inbetweens added Ken Muirhead on lead vocals in time for another shot at the Battle of the Bands, this time taking out the top prize. Rob Guest and Apparition took second place; Mark Williams and The Face took out third.

With their school days only just behind them, they moved to Auckland, chaperoned by Mrs Rabbett.

With their school days only just behind them, and under contract to Benny Levin, they moved into a rented house in Glen Innes, Auckland. They were equipped with amps and speakers from Jansen, and still chaperoned by Phyllis Rabbett. Fellow southerner Craig Scott, who’d won a Battle of the Bands final the previous year with Revival, joined them as a flatmate while being groomed for a solo career.

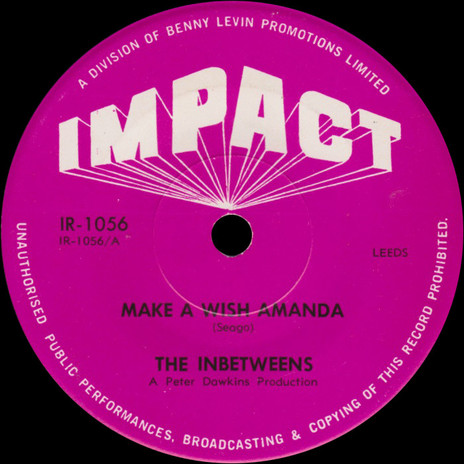

Their early engagements were a mix of weddings, dances, parties and concerts. They were signed to the Impact label alongside stablemates Ray Columbus and Bunny Walters.

Cover song formula

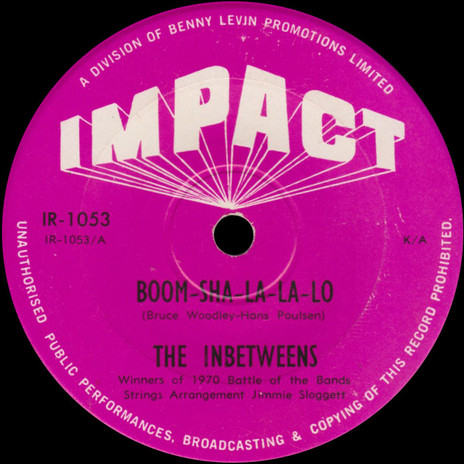

Benny Levin was looking for airplay shortcuts, insisting The Inbetweens and others make a pre-emptive strike by recording versions of singles already charting overseas. In June 1970 they recorded at Stebbing Recording Studios.

‘Boom-Sha-La-La-Lo’, a cover of an Australian song by Hans Poulson and written by Bruce Woodley, was a finalist in the 1970 Loxene Golden Disc Awards, reaching No.18 on the national charts. The band insisted on a “heavier version” of Lennon-McCartney’s ‘The Night Before’ on the B-side.

“Benny saw us as a tweeny sort of a pop band. We were into Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple but he was the manager, so we did what we were told. If people came along expecting to hear songs like our first single, they would have been bitterly disappointed,” says Tony.

With the success of that first single, Levin began booking them into larger gigs and touring them beyond Auckland. Touring and living together inevitably resulted in some tension. It wasn’t exactly luxury accommodation. There are stories of the boys using old socks to plug holes in the wall and differing views on personal hygiene.

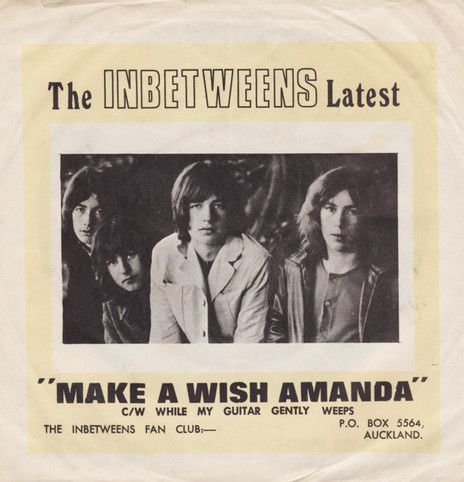

During one disagreement singer Ken Muirhead was asked to leave and he headed back to Dunedin. That left Tony to handle the lead vocals for their next single, ‘Make A Wish Amanda’, written by Mike Leander and Eddie Seago, and originally released in March 1970 by Gary Glitter’s Friendly Persuasion.

This second teenybopper track peaked at No.20 on the national charts in February 1971. Tony regrets the last-minute decision to add their version of ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’ (by George Harrison) on the B-side.

The band played the Bowl of Brooklands in New Plymouth with Tommy Adderley, backed Bunny Walters and then Australian Russell Morris on his national tour, supporting hit single ‘Sweet Sweet Love’. “We’d back any of the solo artists Benny brought in,” says Tony.

Guest invited to join

It was a whirlwind 18 months for The Inbetweens. They’d been propelled into the nascent Auckland scene and lost a singer between two charting singles. But they had definitely graduated from being the new kids in town to a major drawcard in and beyond Auckland.

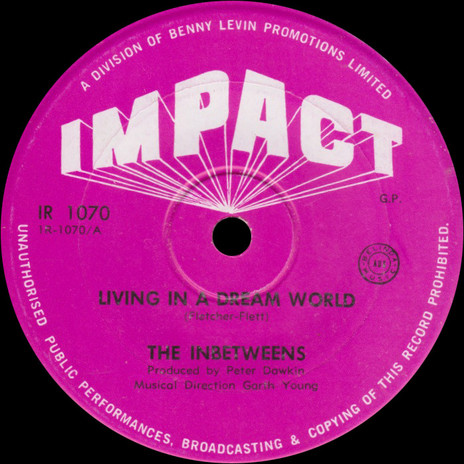

At a gig in Mt Maunganui, they caught up with Rob Guest and Apparition. With a little coercion Guest agreed to join them in time for their next Benny Levin chosen single, ‘Living In A Dream World’ (Fletcher/Flett), produced by Peter Dawkins.

The release, which continued to defy the band’s live sound and direction, dropped with hardly a ripple late in 1971.

Rabbett insists it was always the music and the enjoyment of playing that kept band members enthused. “It was never about the money ... We never made any money that I saw. As long as there was enough for a rice risotto at the end of the day that’s all that mattered.”

An important part of the 1970 Battle of the Bands prize was a cruise liner trip to Australia.

An important part of the 1970 Battle of the Bands prize was a cruise liner trip to Australia which they took in 1972. A booking agent scored them work around the nightclubs and bars of Sydney, including Whiskey a Go Go, the Stagecoach and Fox’s Den in Coogee.

They played the traps like any journeyman circuit band, without much fuss or fanfare and in the midst of it they lost their lead singer. “We were running out of money and energy and Lew Pryme offered Rob a solo career back in New Zealand. They wanted to make him a TV star.”

Original trio again

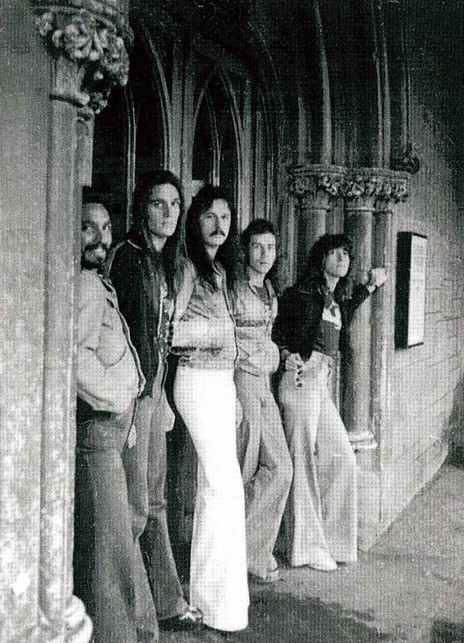

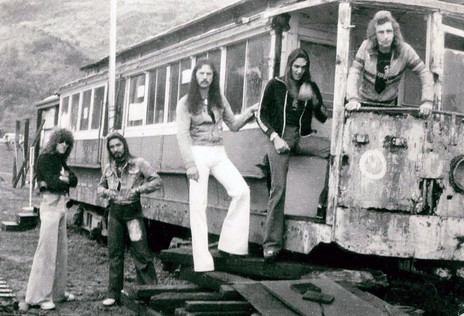

The Australian experience was enough for Murray Newey, who called it quits and later got involved in the film industry. It was back to basics for the original Inbetweens trio of the Rabbett brothers and bassist Roland Farmer, who returned to Auckland where the name quickly got them bookings.

They scored a residency at Hugh Lynn’s Freeflight Club playing West Coast rock, Eagles, Doobie Brothers, Joe Walsh with a bit of Zappa thrown in for good measure ... and Gary Glitter.

Because Glitter had two drummers, they recruited Dave Bailey to play alongside Paul Rabbett. Then Len Worthington joined on keyboards, bringing the coveted Hammond organ sound. While the unit held their own for about nine months, they were losing their mojo and bass player Roland was looking for an out.

A respite from the mundane came in 1975 when Chris McCarthy, guitarist and founding member of 1971 Battle of the Bands winners Tramline, ran into Worthington who suggested he come down and have a listen to The Inbetweens.

McCarthy, having just returned from a failed attempt to crack the Australian market, agreed to step in, bringing a wealth of musical knowledge and his own original material. When Roland Farmer moved on, Chris’s brother Neville, another Tramline original, joined on bass.

A drug squad raid on the Freeflight Club saw friends of the band arrested: that was the last straw for Paul Rabbett, who threw in the drummer’s towel. “The band wasn’t directly involved but our friends were – and there were pretty heavy fines in those days, even for pot,” says Tony.

With their newly expanded repertoire and Chris introducing his passion for the Isley Brothers, Brothers Johnson, rhythm & blues and Bowie’s more funky material, The Inbetweens had a new point of difference.

Dual club residency

They scored a dual residency at Johnny Tabla’s Shantytown under the Civic Theatre and Gatsby’s in High St. They played a month at each venue from Wednesday through to Saturday 9pm to 3am.

“Whichever bar we were in got packed out. Chris was a good songwriter so eventually we started playing mostly originals,” says Tony.

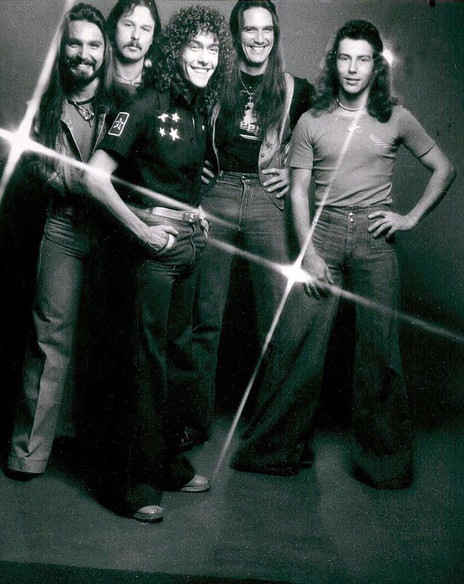

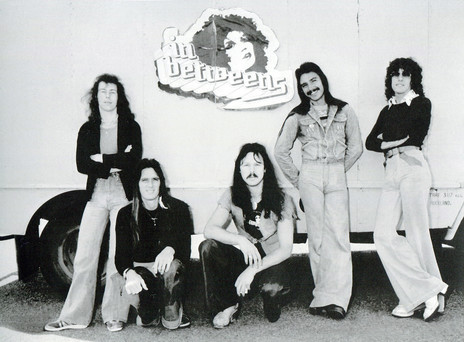

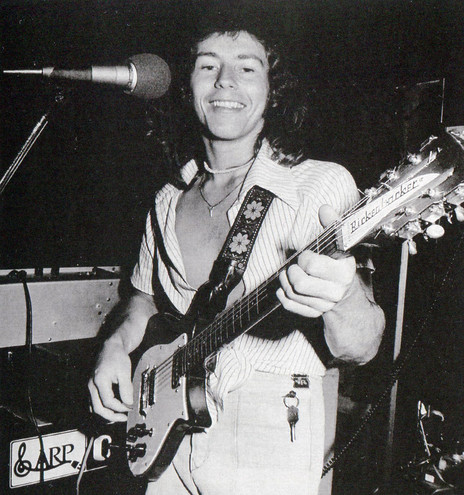

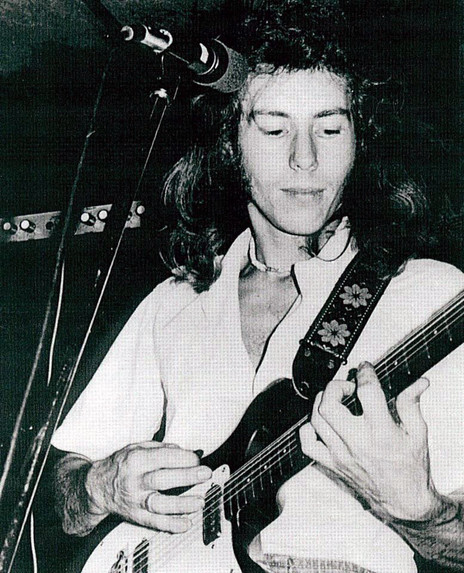

The band, having scored a sponsorship from a jeans company, were all decked out in denim flares except Chris McCarthy. He had worked as a knitwear technician at Sonny Elegant Knitwear in Mt Eden and designed his own gear including a jumpsuit, imagining himself as a kind of Mick Ronson in Bowie’s ‘Jean Genie’ era.

Drummer Dave Bailey took a cassette recording of one of the band’s originals to Eldred Stebbing who signed them to his Key label and began recording sessions – between the radio ads and jingles the band often backed for producer Murray Grindlay.

“Often when you played back those big 16-track two-inch masters you had to skip past a couple of jingles to get to the next song,” says McCarthy.

they wore denim flares, except Chris McCarthy who designed a Bowie-style jumpsuit.

The Inbetweens were laying down tracks while an early version of Anteapot (soon to become Dragon) and Hello Sailor were starting to make their first forays into the studio ... a young high schooler named Dave Dobbyn often sat and watched their sessions.

With first pressing of the single ‘I Can’t Stop Loving You’ in his hands, McCarthy – who had written the song – drove to Radio NZ and asked Kevin Black, in his pre-Hauraki days, if he would play it. “He said ‘You don’t want too much do you? The normal way is we do a deal with the record company’.”

Blackie said he’d listen to the six-minute long track, unusual for a mid-70s soft rock, and if he liked it, it would get airplay. McCarthy was ecstatic when driving up to his mother’s house later that day, he heard their song being played … then it went on rotate.

Album of originals

Their debut self-titled album, engineered and co-produced by Phil Yule, was released later in 1976. With their popularity enhanced by radio play, Tabla’s clubs were packed. The original material was as eclectic as their live shows: experimental rock with a smattering of funk.

The song ‘Mr Funk’ for example, was written by McCarthy about a patron who was a stylish dresser and a kind of dancefloor barometer. “If he got up then others would follow.” (The track was later included on the 2017 Heed the Call compilation.)

Rabbett recalled young Dobbyn asking if he and his new band Th’ Dudes could use their gear to play a couple of songs between sets at Shantytown. Hello Sailor did the same.

The Inbetweens took a break from the demanding nightclub scene in Auckland for a couple of weeks, heading south to Christchurch to play the Aranui Tavern. After the grueling nightly routine at Tabla’s clubs of playing from 10pm until 4am, the Aranui’s 8pm to 11pm was like a breath of fresh air.

Trying to please the city folk with the latest chart releases and the rock brigade with heavier prog rock material was also getting tiresome so they decided to quit Auckland and try for the pub circuit.

Tabla wasn’t keen because they were bringing so many punters to his unlicensed clubs. “We basically started an argument, goading him ... ‘if you don’t like it then get rid of us’ ... so he did. It was a chicken’s way out. In hindsight we should have just said ‘we are leaving’.” says Tony.

Joining the pub circuit

Playing only three nights to about 40-500 people was much more enticing, so they bought a truck and joined the pub circuit.

Len Worthington was “an Arthur Daley-type guy” according to Rabbett, a hustler who knew how to negotiate the best deal for the band. “For the first time we started to make some decent money.”

They were now drawing a weekly wage from Lion Breweries and provided with accommodation. That also meant taking whatever gigs they offered: one week in Dunedin, two weeks in Tokoroa. “That was your job and it was particularly hard on family life,” says McCarthy.

They came back to their favourite gig at the Aranui Tavern, playing about three months of the year from Monday to Saturday plus Saturday afternoons.

Toward the end of the 70s however the breweries began selling off their pubs and instead of a regular wage, bands were offered a percentage of door takings. It was music industry version of market economics. A bad night might not even cover expenses.

“We knew our time was up ... we were getting tired anyway and close to breaking up so we decided there’d be nothing lost if we went overseas for a while,” says McCarthy.

Although they had recorded a second album of originals at Stebbing’s it was shelved. According to the Stebbing history Wired for Sound, with the band about to head overseas there seemed little point in renewing their contract; which also meant Eldred Stebbing didn’t want to release the album.

Perhaps Stebbing saw Hello Sailor as a better commercial proposition than the experimental rock of the Inbetweens.

McCarthy reckons Stebbing saw Hello Sailor as a better commercial proposition than the experimental rock of the Inbetweens. “They played me the song they were working on which had a funny name ... I know it today as ‘Gutter Black’.” The lack of interest in The Inbetweens’ album could also have been attributed to the news that the band was thinking of heading offshore.

LA here we come

In 1978 brothers Chris and Neville McCarthy went to Los Angeles to check out the prospects and caught up with Hello Sailor at their house in Laurel Canyon, where they were struggling to make an impact.

Sailor’s manager David Gapes thought the Inbetweens, who were a little older and rockier, might stand a chance, so it was all on ... perhaps a three-month trial might give them a taste. “We didn’t really put a lot of thought into it, we just agreed, and we were off a few weeks later,” says Tony Rabbett.

There was a slight glitch though. The American Consulate insisted they couldn’t work. They reassured officials they were only talking to recording studios, so it was duly stamped in their visas: “not to perform live for paid or unpaid work”.

Chris, Neville and Lenny started browsing through the newspapers looking for equipment and latched on to a seller who also happened to be a band manager and promoter and a friend of Earth Wind & Fire.

They were warned by their new manager and others that playing covers was not the done thing. They were groomed, advised about sound and presentation and crowd interaction and stuck to material from their two albums of originals.

They got to play all the top bars in LA and Santa Monica, including The Troubadour and the Whiskey A Go-Go in Hollywood.

Among the unknowns gigging at the same venues were The B52s, Martha Davis and The Motels, and guys “dressed in Beatle suits” who had just changed their name from the Sunset Bombers to The Knack. “Everyone was hanging in there hoping they didn’t have to go back to a day job,” says McCarthy.

Gambling on success

The manager, producer and record company were investing in the band, believing that if something great did evolve everyone would share in the success which meant no cost for studio time, production or engineering.

“The producers started picking through songs from our albums and basically wanted to rewrite everything. Even if you had a great idea they wanted to change it and adjust the lyrics or what you were playing. That was the American way, not the do-it-yourself Kiwi way,” says McCarthy.

They began recording at Indigo Ranch Studios in the Malibu Mountains, where they stayed in chalets for three days working with Chris Brunt who had engineered Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions. For keyboards, the band borrowed Larry Dunn of Earth Wind & Fire.

Money and morale were running low. Living and rehearsing in the same house in San Fernando Valley was the cause of some friction. “The hour on stage was our favourite hour ... getting by for the next 24 was the hard part, with a big wait between gigs,” says McCarthy.

Drummer Dave Bailey was an American citizen so Tony Rabbett used his name to take on some part-time work but blew it one day when he forgot who he was.

He’d also learned his girlfriend back home was having a baby so he returned home, then became conflicted. “After seeing my baby I went back to LA to give it another go and realised that was a bad idea,” says Rabbett.

Besides, the work visas were coming to an end and while green card applications were in, it became a case of step up or step out. “As soon as word gets out that you’re having problems the phone stops ringing ... the best thing is we didn’t get into debt,” says McCarthy.

End of an era

Most of the band were back home by March 1980. McCarthy stepped up to help brother Neville in several bands, including Perfect Strangers with Len Worthington and Karl Gordon from Golden Harvest on vocals – until he called it quits about 1984 and got a real job.

the shelved 1978 Stebbing sessions were released digitally IN 2014 as ‘Night Time in the City’.

Rabbett joined new wave unit The Newz, fronted by Simon Darke, which carved a niche in Christchurch. They released a single, ‘Accident Prone’, and an album, Heard The Newz.

Australian promoter Michael Gudinski took them to Melbourne where they worked the circuit pending a recording contract, but after a couple of months they weren’t earning enough to survive so they split and headed home.

Rabbett began managing Holden Sound’s hire department, setting up the technical side for concerts. In defiance of his father’s challenge he is still a professional musician, more than 50 years after forming the Inbetweens.

The Inbetweens were an enigma: their early, sweet pop recordings were nothing like their hard-edged live shows. They started as underage hopefuls and ended up high profile but media-shy pioneers of the pub rock circuit.

So what happened to the Indigo Ranch recordings? “I did have copies of them but I lost them,” says Rabbett. Their post-LA swansong however did come in when the shelved Stebbing sessions from 1978 were released on streaming services as Night Time in the City in 2014.

The album stands alongside any of that soft-rock era for its musicianship, strong compositions and originality, and is deserving of kudos despite being archived for 30 years.

“They even made a cover for it,” says McCarthy. “Oh well, they own the master tape so it’s their property. No one really knew that at the time or asked what the deal was. When someone with the latest flash gear wants to record you, you just jumped at it.”

--

Read more: “Inbetweens Are In” – a 1970 Playdate feature