His last stand had been a run-of-the-mill gig at De Bretts Hotel, in High Street, fronting Cruise Lane. The band had just finished and were still on stage when two drunken gang members charged at Grindlay and bass player Mike Wilson.

“Mike struck out with his bass and they were just getting angrier,” Grindlay remembered. “We faced them and left the stage. There were only two of them but the little guy was so full of hate. The bouncers finally came and shepherded them out, but the little guy threw a shot glass and hit me under the eye.

“When we asked the bouncers what had taken them so long, they said they didn’t want to start a fight because the guys were in a gang! Mike and I saw the manager later and he just wasn’t interested. That’s when it all turned around for me, changed my whole life. I thought, ‘I’m not playing in those places anymore.’ ”

He ventured out into the jingle world where he found huge success with campaigns for Crunchie, BASF cassettes, Europa and many others.

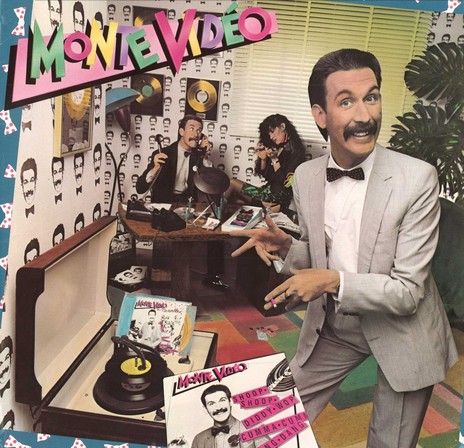

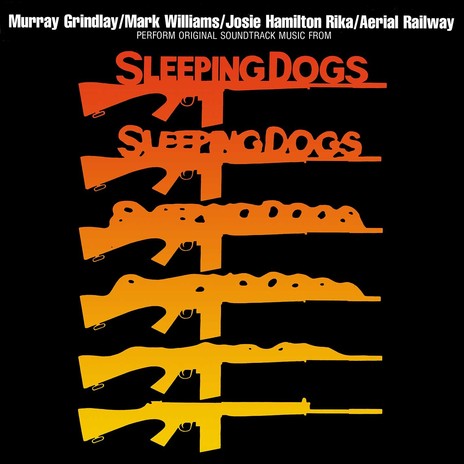

He ventured out into the jingle world where he found huge success with campaigns for Crunchie, BASF cassettes, Europa and many others. He wrote music for movies such as Sleeping Dogs and Once Were Warriors and there was even an accidental tilt at world pop domination as Monte Video with the hit song ‘Shoop Shoop Diddy Wop Cumma Cumma Wang Dang’.

Today, the walls of his toilet are adorned with gold and platinum albums for his production and/ or writing on releases such as the America’s Cup anthem of the 1980s, ‘Sailing Away’, John Grenell’s ‘Welcome To Our World’, the Red Nose Day song ‘You Make The Whole World Smile’, the Greenpeace remake of The Mutton Birds’ ‘Anchor Me’, Goldenhorse’s Out Of The Moon and the Once Were Warriors soundtrack.

Born on October 24, 1949, and raised in Stenhousemuir, Scotland, Murray Grindlay arrived in New Zealand at the age of 13 when his father, an instrument engineer, was transferred to Auckland. He had wanted to be a musician from the age of nine or 10 when he was inspired by the music of The Everly Brothers, Conway Twitty and Elvis Presley.

The first person Grindlay met in Auckland would figure heavily in his future life in music. “We stayed at the Great Northern Hotel for a few weeks while my father and mother were getting us a house sorted out,” Grindlay remembered. “One day I walked out of the city for a ways to Orakei Beach and I met Neil Edwards.”

The two youngsters chatted and found some common ground with a shared love of pop music, and when the Grindlays settled in St Heliers they found themselves schoolmates at Selwyn College – Grindlay in the fourth form, Edwards in the fifth. Another fifth former was Mike Wilson, who would also become a prominent musical partner in the coming years.

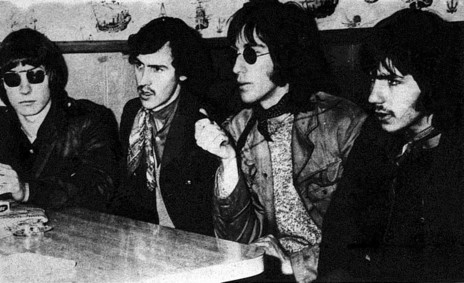

Grindlay’s earliest forays into music were singing at rehearsals for Edwards’ fledgling band and as part of a short-lived line-up called Moses & The Munks, which also featured future Red Hot Pepper Robbie Laven and future Ticket frontman Trevor Tombleson, and played at “strange places like Pakuranga coffee houses”.

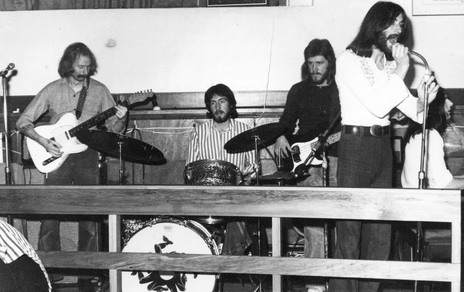

He became the singer in a Glen Innes band with bass guitarist Ross Guiniven and drummer John (Michael) Donnelly that morphed into The Soul Agents with the addition of guitarists Clarry Schollum and Kim Rauch. “We were more of an English covers band. We used to do Yardbirds and Manfred Mann and The Animals, all that sort of stuff.”

The Soul Agents became one of the “lesser bands” at Eldred Stebbing’s Galaxie Nightspot but caught his attention enough for him to record and release their cover of Them’s ‘If You And I Could Be As Two’ b/w The Easybeats’ ‘For My Woman’ on his Zodiac label. However, Grindlay had his sights set on another of the Galaxie’s draw cards.

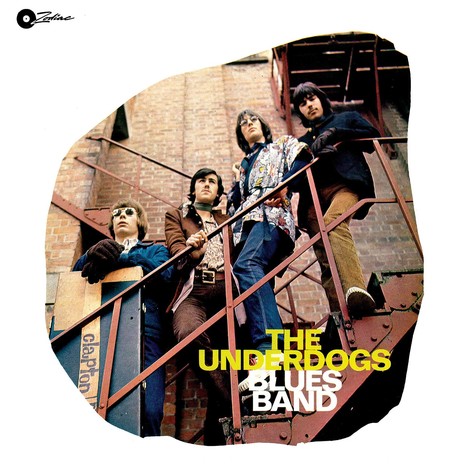

"As soon as I saw The Underdogs, I thought, ‘Oh, that’s the band I wanna be in.' "

– Murray Grindlay

“Of course The Underdogs were there at that time,” he said, “and as soon as I saw The Underdogs, I thought, ‘Oh, that’s the band I wanna be in.’ Easily the best. Well, except for The La De Da’s of course, who were always wonderful. But I just liked the blues thing, it hit me straight away.”

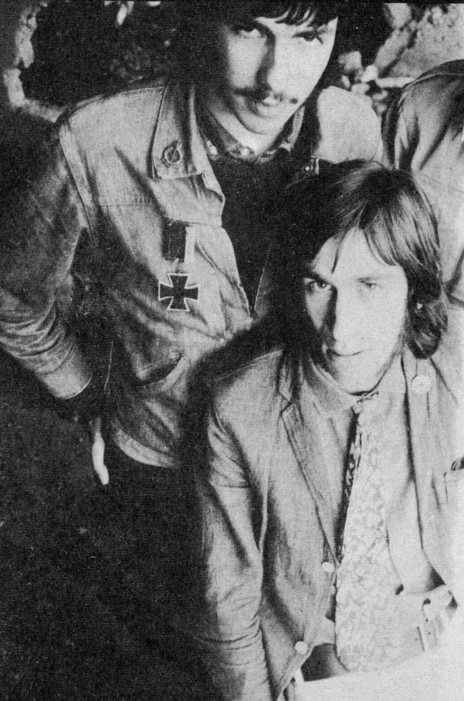

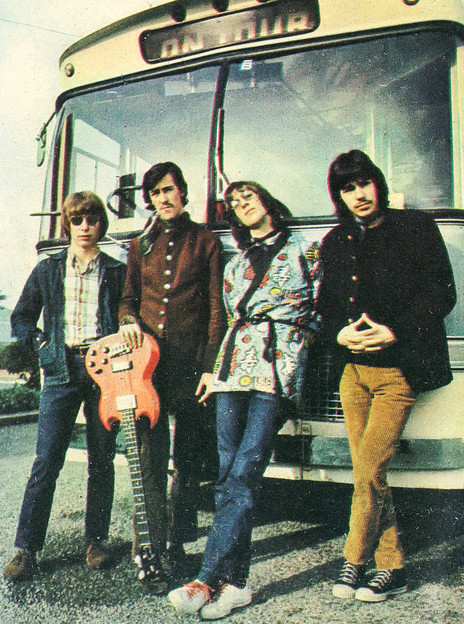

It was the original Underdogs that floored Grindlay – Archie Bowie on vocals, Tony Rawnsley on rhythm guitar, Harvey Mann on lead guitar, Barry Winfield on drums and his schoolmate Neil Edwards on bass. When they replaced Bowie and Winfield with former Dark Ages members Mick Sibley and Ian Thomson, The Underdogs became a somewhat slicker outfit.

“But I still thought, ‘No, no, no, no, it’s only a matter of time. I can get into the band.’ So I just hung around really and finally they asked me to join and of course I didn’t even think about it. I said, ‘What’s taken you so long?’ ”

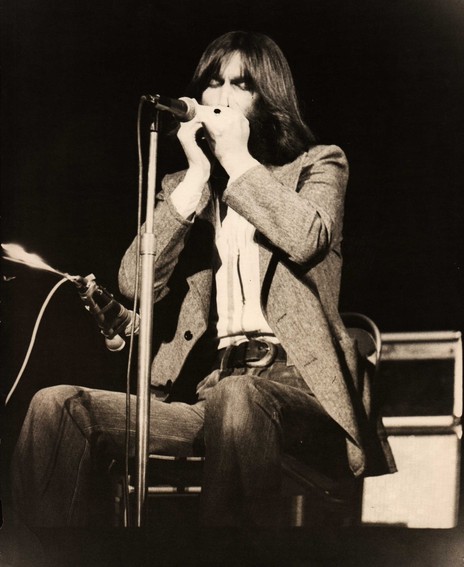

With Grindlay on vocals and harmonica, Mann and Edwards, Lou Rawnsley replacing his brother Tony on guitar and Tony Walton replacing Thomson on drums, they became resident at the Galaxie with The La De Da’s. “That band was certainly a lot more than the blues thing. Like, we were doing Zoot Money songs – you know, like ‘Big Time Operator’ – and all that sort of stuff, because the kids loved it. We were quite commercial really.”

In quick succession The Underdogs released their debut single ‘See Saw’ on Zodiac and made their first appearance on the NZBC’s C’Mon show. It brought them a bigger audience and they recorded their classic single ‘Sitting In The Rain’ before Mann quit and the four-piece embarked on the C’Mon 67 tour. The John Mayall cover was the band’s idea but Stebbing chose a take where the band members were mucking around, Grindlay giggling through the refrain.

Bass guitarist Dave Orams replaced Edwards and was in turn replaced by George Barris. “We had changed completely,” Grindlay said. “We were back to the blues, although still pretty white blues. Like, Cream were really big and we were doing ‘Spoonful’ and all those type of songs, and one song would last the whole set. It was that sort of a band.”

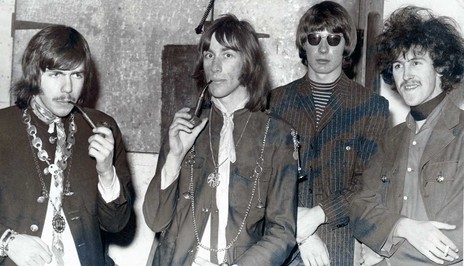

When The Underdogs split, Grindlay joined The Brew, coming under the tutelage of 40-something-year-old American saxophonist and drummer Bob Gillett, and they changed their name to The Australasian Blues Champions (aka The ABC). With Gillett on drums, the rest of the line-up was Harvey Mann on guitar and Doug Jerebine on bass.

“And we proceeded to rehearse, God, it must have been about six months, maybe even longer, but we never got one gig. No one would have us because of Bob. You know, Bob was this old guy – well, in those days considered old – who dressed like a circus performer and had a huge eye painted in the middle of his bald head, and it didn’t endear him to the [Auckland club owner] Fred McMahons of this world.”

The best option was to re-form The Underdogs with Grindlay, Mann, Lou Rawnsley and Ian Thomson, who was soon replaced by Doug Thomas. Through living with Bob Gillett, Grindlay and Mann had been influenced by San Francisco band Moby Grape, and The Underdogs managed to pull off their intricate harmonies.

The repertoire changed again when Chaz Burke-Kennedy took over from Rawnsley. “We’d kind of moved on a little bit. The Band had just come out, so we were doing Band songs. We were doing Sly and the Family Stone and we were also doing Frank Zappa songs.”

Their next single was Zappa’s ‘Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance’ (recorded prior to Rawnsley’s departure), but not before Eldred Stebbing insisted on changing the title to ‘There Will Come A Time’ before allowing its release on Zodiac. The B-side was a cover of the Electric Flag instrumental ‘Fine Jung Thing’. The Underdogs split soon after.

At the close of the decade, Grindlay got a call from his old Selwyn College mate Mike Wilson in Sydney, who was in need of a singer. After a couple of months working in a Mount Roskill factory to raise the fare, Grindlay arrived in Australia joining Wilson (guitar), Neil Edwards (bass) and Glen Absolum (drums) in rehearsal.

But the alarm bells started ringing when the new arrival played the others his newest discoveries, Jerry Jeff Walker’s ‘Mr Bojangles’ and Neil Diamond’s ‘Kentucky Woman’. “They just sort of looked at me and thought, ‘Oh, fuck,’ ” Grindlay laughs.

“Oh, it was hopeless. I was already into my Jerry Jeff Walker period and they were doing Cream songs and I just didn’t want to know by then. I mean, ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’, there’s no way I wanted to sing that ever again in my life.”

Grindlay starved for a couple of weeks before being contacted by former New Zealand bandleader Claude Papesch.

Grindlay starved for a couple of weeks before being contacted by former New Zealand bandleader Claude Papesch, whom he knew from the Embers club in Auckland. Papesch had crossed the Tasman as organist with The Electric Heap, which also featured Bruno Lawrence on drums and Tim Piper alternating between guitar and bass.

When they split up, Papesch and Piper joined Chain long enough to record their first single for Festival, ‘Show Me Home’, but Papesch was now putting his own band together called Savage Rose, recruiting Grindlay on vocals alongside expat guitarist Red McKelvie and Australian drummer Ace Follington.

The new band worked seven nights a week in Sydney – five at the Whiskey Au Go Go, one at the Hawaiian Eye and one at the Electric Circus, shifting Papesch’s heavy Hammond B3 between venues. With Papesch initially playing the bass pedals on his organ, they later acquired a bass player on the strength of his Dynacord PA system. “I’d sort of been used to just plugging into the bass amp,” says Grindlay.

“It was a heavy band because Claude was at the height of his drug thing. There were criminals everywhere, which none of us were used to except Claude, because he used to hang out with the criminal element because that’s where the drugs were. But, at the same time – bless him – old Claude was great. Shit, he was a good musician and he taught me heaps. You know, he really knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t know.”

When Savage Rose folded, Grindlay formed Grindlay’s Choo Choo – a name Bob Gillett had coined when offering up names for The Australasian Blues Champions – with Yuk Harrison on bass, Trix Willoughby on drums and Tim Piper on guitar. “This was the maddest band I’d ever been in in my life. And I mean literally completely insane, everyone except me.”

Grindlay would arrive at a gig at the likes of Caesar’s Palace to find Willoughby behind his kit with a brown paper bag over his head with slits cut for his eyes, randomly hitting drums and making noises. Harrison was drinking heavily and would usually be sitting on stage mumbling, “I’m sorry, man, I can’t play,” and Piper would be completely unfazed by the others, gripping his guitar with only five strings on it, asking Grindlay, “What’s the problem?”

“We hardly played anywhere. I actually ended up having a sort of a minor nervous breakdown and just woke up one morning in Paddington and just got a taxi to the airport and came straight back to New Zealand, I didn’t tell anyone. As soon as I landed in New Zealand it was like, ‘Oh, thank God.’ ”

Back in Auckland, Grindlay moved in with Mike Wilson, his wife Lois and their two kids and got a job mowing lawns for the council, until colliding with a tree and launching his ride-on mower halfway up it.

There was an attempt to get a band going with former Le Frame guitarist Fred Bower and former Underdogs drummer Doug Thomas. Grindlay even got a job as a gardener at Oakley Hospital for the express purpose of breaking Thomas out of the institution. The band may have played one gig at the Tabla but it never really got past the rehearsal stage.

Around the same time, Grindlay received a call from Eldred Stebbing to replace his former Underdogs bandmate Harvey Mann’s vocals on the poor-selling Space Farm album so Zodiac could re-release it. “That was a huge mistake,” Grindlay said. “It was a complete mismatch. It was terrible, but, like, he paid me 50 quid, and, my god, it was a fortune at the time and also Harvey had given clearance.

“But, you know, I mean, here’s a guy who’s discovered Jerry Jeff Walker, who’s discovered all these great lyricists, you know, all these wonderful writers, and here I am in Stebbings singing, ‘Flying through the canyons of my mind.’ What the fuck?” The self-titled album was reissued on Ascension in 2000 with Mann’s original singing restored.

By now heavily into Walker, Randy Newman and Joe South, he and Wilson hit upon getting work as a duo – Grindlay singing and playing harmonica, Wilson on acoustic guitar. They struggled to find a suitable venue until Nick Villard gave them an opportunity at his club the Embers, where they worked in unison with resident band Cruise Lane.

“People like Creedence Clearwater Revival would come to the club and they’d sit and listen to Mike and I. John Fogerty and the other two, it was just a trio by then, and they’re sitting right in front of us at the Embers, and I’m standing up there in my overalls with ‘Oakley Hospital’ written on them, and Mike’s sitting on the organ seat playing the guitar. They all used to come to the Embers because the Embers was the cool club.

“We used to just go through these songs and they all loved us. Of all my bands that I was ever in, you know, that was actually the one I enjoyed the most – by a mile, really. Because it was such good music, and all of a sudden I was singing differently. You know, like, I wasn’t yelling anymore,” Grindlay said.

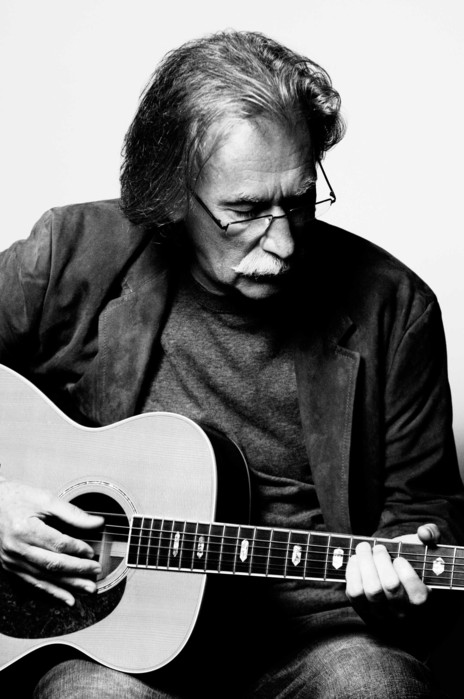

The result of performing songs by such intelligent lyricists as Walker, Newman and South was that Grindlay began penning his own songs. “I wanted to write – that’s what I wanted to do. More than anything I wanted to write, because I had them in my head constantly. And I’d only been playing the guitar for … I only started playing in the last year I was in Australia.”

Once the Embers resident band Cruise Lane splintered in mid-1972 – half of them trying their luck in Melbourne – Grindlay and Wilson were recruited. Early the next year Cruise Lane’s second single was released on Shoestring Records with Grindlay’s ‘Ain’t No Need’ on the reverse. “That was a fairly pathetic effort,” Grindlay laughed. “That would be one of the first things I ever wrote.

“It was quite a good time for me, as well, in a New Zealand band because I think Nick (Villard) might have been paying us 70 bucks a week each, which was a veritable bloody fortune in those days. I’d actually got married by this time and my rent on a beautiful downstairs part of a townhouse in Parnell was $16 a week, so there was plenty left over for all the other stuff.”

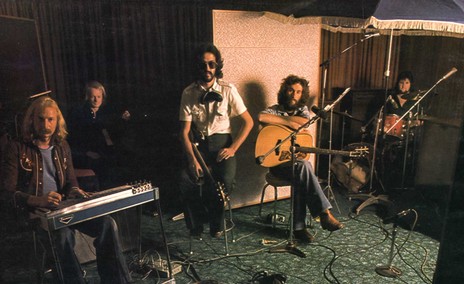

Not long after the Embers residency ended, Cruise Lane folded and Grindlay and Mike Wilson put together a new unit, again named Grindlay’s Choo Choo, with Steve Wilson on guitar, Paul Hewson on piano and Bruno Berens on drums, but it petered out after only a couple of gigs.

His next project was an acoustic trio with guitarists Lou Rawnsley and Tony Pilcher called Smoko. They were the first band to play the Windsor Castle but were primarily put together to support the Muddy Waters Band through New Zealand and to open for John Mayall’s two Auckland shows, on one occasion getting Mayall’s guitarist Hi Tide Harris so stoned he couldn’t play.

It was a fruitful time for Murray Grindlay finding his feet as a songwriter.

It was a fruitful time for Murray Grindlay finding his feet as a songwriter. His ‘We All Have To Find Our Own Way Home’ was released on Family as Cruise Lane With Lou Rawnsley, Josie Rika And Dave Stewart, and ‘Marie’s Garden’ (Grindlay) b/w ‘Lou’s Song’ (Grindlay/ Lou Rawnsley) was released on Shoestring as Grindlay, Wilson And Rawnsley. His first solo single, ‘Nova’s Song’ b/w ‘Thoughts On Returning Home’ was released on Zodiac.

Cruise Lane re-formed with two more strong songwriters joining the fray in guitarist Red McKelvie and Paul Hewson for a residency at De Bretts. Grindlay was in awe of Hewson’s songs and the band demoed a bunch of them intent on recording a new single.

“We used to do all Paul Hewson’s originals at that time, and they were good, they were fun to do. He was a good writer. He was probably one of the best writers that I’d ever met locally so far. A lot of people don’t know that he was a really good acoustic guitar player, too. He could do all that Bob Dylan stuff like ‘Oxford Town’ with all the finger-picking.”

But Cruise Lane came undone after Grindlay was assaulted at De Bretts. There was no way he was going back to the pubs but he needed to find a way to earn some money from music. “I’d sung a few jingles over the previous few years. Occasionally I’d been called in to sing a jingle for someone like Jimmie Sloggett or Captain Bob Smith. I thought, ‘Well, these jingles – I could write these.’ ”

He packed up his singles and demos and hit up the ad agencies with a plan to approach jingles as actual songs rather than out-and-out advertisements. “I came along with this idea, ‘No, let’s not do them like jingles, let’s not even mention the product where we can get away with it and even make all the lyrics like a song, so that they’re songs.’ I was just in the right place at the right time. It was time for a changing of the guard and there I was, ready.”

Initially, he worked in partnership with Mike Wilson, who would play all the instruments, until deciding to branch out on his own. “I got a little bit restless because everything was sounding too much the same to me, and I wanted to play with more musicians.

“Especially Red McKelvie [back in New Zealand permanently after almost a decade in Australia] I wanted to play with again, because I knew Red would be great for the jingles. You know, he’s that sort of style of guitarist, he’s got that great knowledge of country rock and he sort of knew all about ska and reggae and all that stuff.

“Over the years of jingles I kept on having different bands. Probably each band would last five years or four years and then I’d change,” Grindlay recalled. The first jingles band consisted of McKelvie (guitar), Dennis Ryan (drums), Neil Edwards (bass) and Peter Woods (keyboards).

Grindlay’s most endearing and enduring jingle came about in 1975 with the Great Crunchie Train Robbery campaign.

Grindlay’s most endearing and enduring jingle came about in 1975 with the Great Crunchie Train Robbery campaign. Adman Roger MacDonnell had a complete set of lyrics which Grindlay turned into an almost bluegrass romp with banjo and acoustic guitar. The advert played on TV and in movie theatres for 20-odd years.

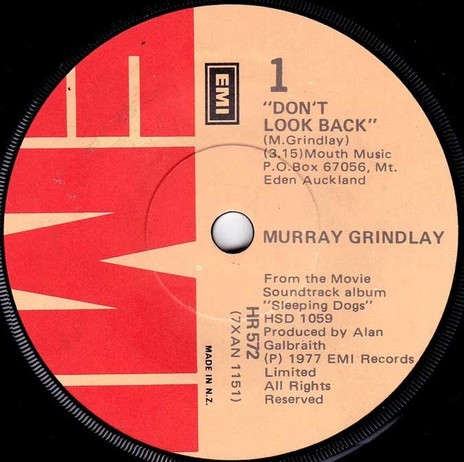

The ad work also brought him into contact with director Roger Donaldson, who requested Grindlay write seven or eight songs for his feature film debut Sleeping Dogs. The songs were recorded at EMI in Wellington by Mark Williams, Sharon O’Neill, Josie Rika and Grindlay, and released as a soundtrack album. His ‘Don’t Look Back’ was the single.

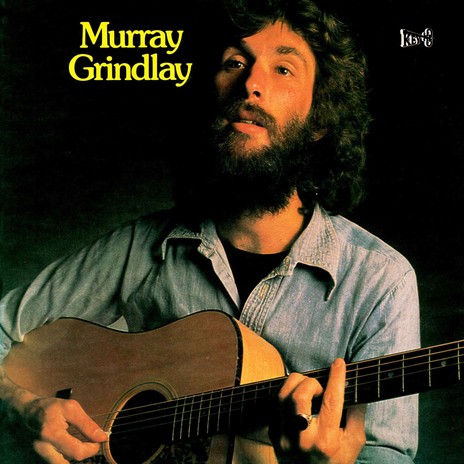

During down time at Stebbing in 1976 and 77, Grindlay had been recording his own songs with his gun jingles band and engineer Phil Yule. He and Yule had mixed the album when Eldred Stebbing stepped in and had Hello Sailor producer Rob Aickin completely remix it for release on his Key label in time for Christmas.

“To be honest, it’s a thing I’d rather forget,” Grindlay recalled. “It was a real mistake to get him to remix my album. There was so much echo. I had a good black-and-white cover that I’d got done but Eldred said, ‘Oh, we can’t have that, they’ll think we’re cheap.’ So he took new pictures and it looks like Murray Grindlay Sings Your Favourite Hymns!”

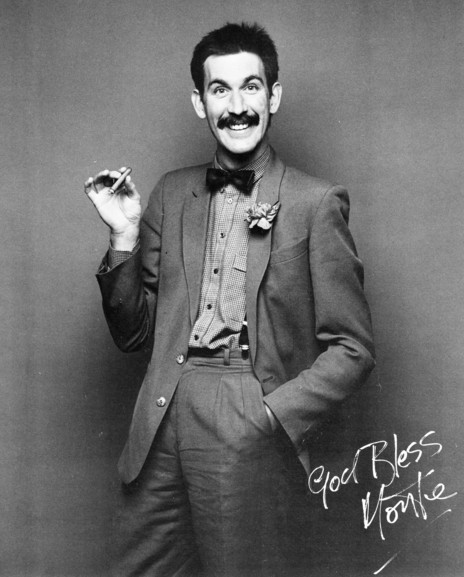

By 1982 he was the go-to man for New Zealand advertising agencies and at the end of that year had the world’s media in a frenzy with an unintentional novelty hit. He’d never stopped writing songs for his own enjoyment and had been working on something with a Dr John-New Orleans feel when adman Mark Ackerman popped round.

Grindlay played him the new song, entitled ‘Shoop Shoop Diddy Wop Cumma Cumma Wang Dang’. “That’s catchy, but you’re doing it all wrong,” Ackerman told him. He suggested Grindlay try it in the vein of Bill Wyman’s 1981 solo hit ‘(Si Si) Je Suis Un Rock Star’.

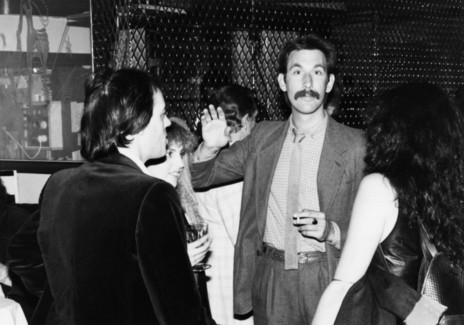

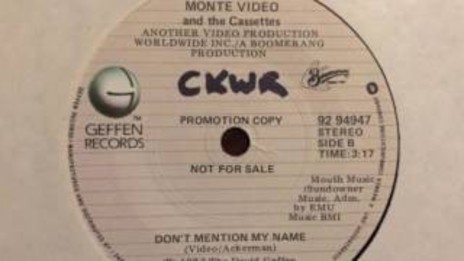

It worked and Grindlay recorded the track with Bruce Lynch providing all the backing on his ARP 2600 synth. Ackerman even had a name for the act – Monte Video And The Cassettes – and directed an outlandish video for the song featuring a cast of drag queens shot at the Peppermint Park nightclub in Ponsonby.

‘Shoop Shoop Diddy Wop Cumma Cumma Wang Dang’ and Grindlay’s alter ego were a runaway success. The single was released on Mushroom NZ and peaked at No.2 on the charts – where it stayed for three weeks in February 1983, unable to dislodge Marvin Gaye’s ‘Sexual Healing’ from the top spot.

Released on Mushroom in Australia, where it peaked nationally at No.11, its success was helped along by an elaborate back-story cooked up by Ackerman. The Australian press, who understood Monte Video to be an Englishman, were led to believe that due to tax reasons he was travelling in New Zealand and could be contacted there for interviews.

The single’s picture sleeve stated the musicians’ names were “withheld by request” but Ackerman put the rumours around that Ringo Starr and Elton John both appeared on the track. The Aussies fell for it hook, line and sinker and weren’t very impressed when they found out later Monte Video was a New Zealand jingle writer.

In the United States, former New Zealand promoter Barry Coburn had the song released on Geffen Records, and Hall & Oates manager Tommy Mottola wanted to sign Monte. Grindlay got a call from Coburn saying the Geffen office walls were plastered with photos of Monte and they were giving away fake Monte moustaches.

But the novelty wore off pretty quickly and an album and two further Monte Video singles – ‘Sheba (She Sha She Shoo)’ and Grindlay’s favourite ‘Who’s Calling?’ – did little. South African-born former Beach Boys drummer and Rutles actor Ricky Fataar mixed the album.

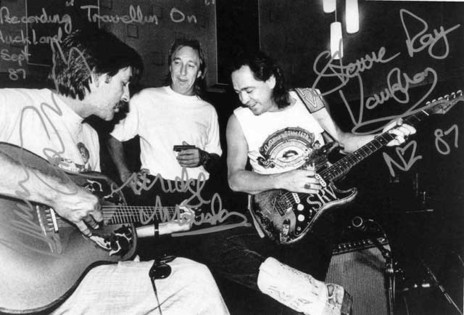

By the mid-1980s, Grindlay wasn’t just writing jingles, he was starring in them too. His second ‘Travellin’ On’ campaign for Europa featured a four-minute commercial following the antics of Grindlay, New Zealand bluesman Midge Marsden and Texan guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan as they travelled through the country. The song became a staple of Marsden’s live show and he later recorded it for his Travel ’N Time album.

The connection with Fataar brought jingles sessions with Bonnie Raitt’s band and Jimmy Buffett’s band when they were in New Zealand, and amongst the international singers Grindlay has employed are American bluesman Taj Mahal (who became a good friend) and Australian soul singer Renee Geyer – “Probably the best singer out of the South Pacific,” he said.

He had also formed a close friendship with keyboard whiz Murray “Star Wars” McNabb. “He became my life-long musical compadre. He was probably the biggest influence on my music ever. Him and I were just perfectly suited for each other, you know.” In the mid-1990s, the pair branched into movie scores with Gregor Nicholas’s Broken English and Once Were Warriors – directed by another of Grindlay’s advertising contacts, Lee Tamahori.

Grindlay’s long association with the Stebbing Recording Centre came to an end in the late 1990s. There was a lot more competition in the jingle world and business had fallen off a little since the heady days of the 1970s and 1980s, but Grindlay and McNabb would still rock up every day to write on the studio piano.

One day Eldred Stebbing called Grindlay up to his office and asked, “Can’t you go do that at home?” Grindlay went back downstairs, packed up his gear and never went back. He spent the next 10 years working out of Revolver in Pah Road. “Revolver had been at me for a year anyway, ‘Come here, come here.’ They were particularly good to me, gave me an office.”

Grindlay co-produced Goldenhorse’s Out Of The Moon at The Lab and Roundhead Studios in 2005 and produced The Electric Confectionaires’ debut album, Sweet Tooth, at Montage Studio in 2007. “Roundhead is the best studio I’ve worked in here,” he said. “There would be 100 different acoustic guitars hanging up and you could use anything you wanted.”

When Revolver closed he moved his operation to Bruce Lynch’s The Boatshed Studio in Bayswater, where he still works with Lynch’s son, Feelers and Zed guitarist Andy Lynch. His long-time collaborator Murray McNabb died of cancer on June 9, 2013.

Grindlay revealed his next project would probably be a blues-based album with Andy Lynch. “I discovered open tuning and I’ve written 15 or so songs using it. I find it takes me to different places. I still think of myself as a songwriter, so I’m probably going to do an album really soon.”

–

Ian Morris on Murray Grindlay's 1977 solo album. Taken from igMusic with permission.