Despite being a household name, Scott was always smart enough to know that fame would be fleeting and he would need to keep a lid on the excesses that blighted the lives of so many contemporary stars both in New Zealand and overseas.

Perhaps this was because Scott was never driven to be a solo superstar; rather, he happened into music when some mates formed a band. Born in 1950 and growing up in Dunedin, Scott attended Kings High School. Musically inclined school friends got together to become The Klap (Sunday afternoon shows at the YMCA saw them use the more acceptable name The Aftermath). Needing a bassist, they roped in Scott, who had made his own bass guitar, styled after the instrument played by Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones. Leaving school, Scott worked at the National Bank for two and half years, performing with the Klap in the evenings and on weekends.

Scott had the best voice, so he dropped the bass to become lead vocalist.

At this time Dunedin was a major base for picket (supply) ships heading to McMurdo Sound. Sailors from these ships provided a ready supply of 7” singles of music that would simply never have made the playlists of straight-laced New Zealand radio stations of the 60s. The Klap scored some of these precious singles by befriending crewmen off ships at the Locker Room in the city, where they changed before heading the city’s bars. The Klap beefed up their repertoire with these American soul and R&B tracks.

In time The Klap discovered that of the band members, Scott had the best voice, so he dropped the bass to become lead vocalist.

The band built its audience to capacity with shows at venues such as the historical Aggie Hall (His Majesty’s Theatre) attracting huge crowds. Changing its name to Fantasy the band turned pro, moved north to Christchurch and scored a six-month residency at The Scene nightclub in Tuam Street.

The members of Fantasy felt that they were ready to record, and headed to EMI’s studios in Wellington. Things did not go well, though it brought Scott back to the attention of legendary EMI house producer Peter Dawkins. Dawkins had first encountered Scott when Johnny Farnham visited Dunedin earlier that year.

Meanwhile fellow musicians The Revival had a six-month residency at Snoopy’s in Chancery Lane in Christchurch. The group was spotted and signed to EMI by Dawkins, who had seen them at a Battle of the Bands heat in Wellington. When Dawkins recommended to manager Trevor Spitz that the band get a new singer, Revival poached Scott from Fantasy. Scott benefitted from the difference in the standard of musicianship, and felt the combination of vocals and music worked immediately. Revival’s repertoire was more in the blues-rock vein than the pop covers favoured by Fantasy.

Dawkins brought the band to Wellington to record their only single, with songs chosen by Dawkins. A cover of the Equals’ track ‘Viva Bobby Joe’ was backed with Revival’s version of English band Locomotive’s proto-ska track ‘Rudi’s In Love’. ‘Viva Bobby Joe’ was a big hit but commercial success was not really what the members of Revival had in mind, and a popular band wasn’t what Dawkins was really after.

He was in fact looking for a successor to Mr Lee Grant and Shane, who had seemingly run their course as hit makers. Dawkins persuaded Scott to leave Revival, move to Wellington and, in the parlance of the industry, “go solo”. There was no ill feeling as Scott’s bandmates wished him well for the future. Those bandmates were no slouches: bassist Rod Coe moved to Australia where he became house producer at EMI, recording a huge roster including everyone from Slim Dusty to The Saints; drummer Bruno Berens was at the birth of New Zealand reggae with Papa; guitarist Eddie Hansen became a guitar legend with Ticket and Living Force.

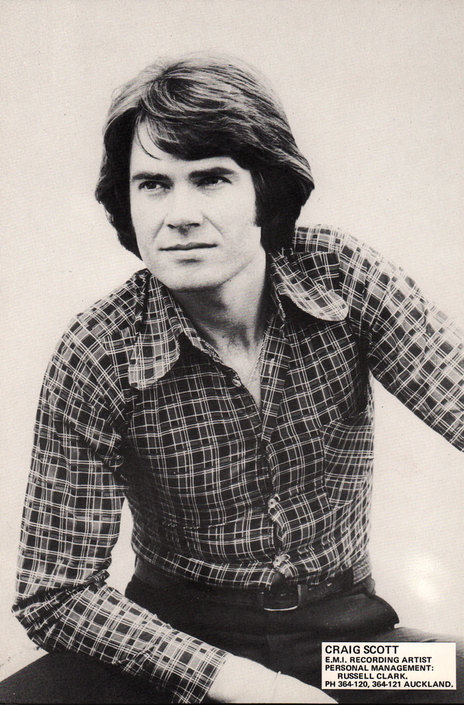

Early 1970 found Scott working in the EMI warehouse packing LP orders for record shops while he made his first recordings for EMI. Those few months in Wellington proved critical as Scott’s friendly personality endeared him to all at EMI, from MD Alfred Wyness to the house electrician. Bruce Ward, in charge of singles at EMI at the time, recalls Scott as standing out from other local artists. “Everyone loved him. We all saw him as one of us. Even when his fame headed into the stratosphere he never got big-headed, never played the superstar. So he always had the backing of the whole company from top to bottom.”

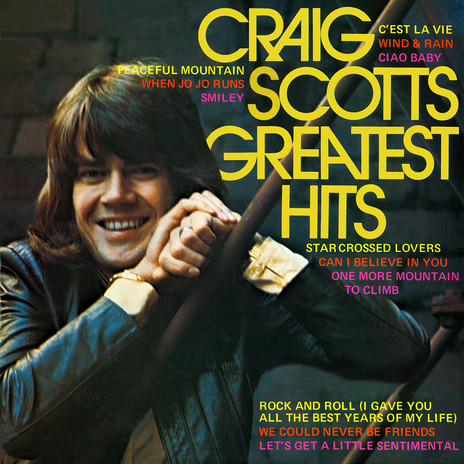

Dawkins and Scott proved a winning combination. Dawkins had a sixth sense for picking hit tracks and outstanding skills as a producer, while Scott had an easy-going yet professional approach to recording. Dawkins and Scott worked seamlessly in tandem, plowing their way through piles of 45s in search of suitable tracks to record. They cannily selected tracks with broad appeal – and, critically, radio appeal. Dawkins produced them to international standard, resulting in a string of hit singles over the next two years. Bruce Ward: “Craig was certainly the biggest star we ever had in my time at EMI – virtually every track he released was a smash hit.”

Scott hit the jackpot with his debut single but not without some initial resistance from the NZBC.

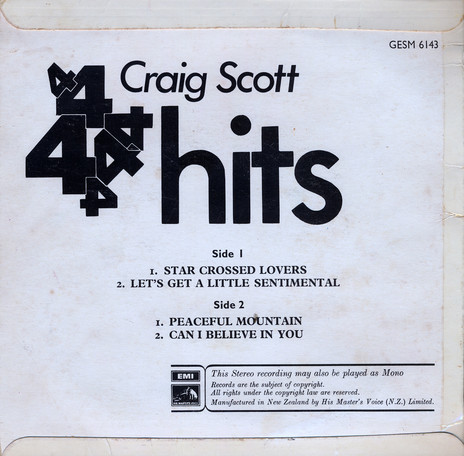

In April his first single was ready for release. ‘Star Crossed Lovers’ had been a huge hit in Australia for Neil Sedaka a couple of years earlier. Scott hit the jackpot with his debut single but not without some initial resistance from the NZBC. Bruce Ward recalls New Zealand’s national broadcaster initially refusing to buy the single for their stations, due to the “controversial” nature of the lyrics. “It’s hard to believe now but in 1970 they thought that a song with lyrics about a Catholic ‘confessing’ that he’s fallen in love with a non-Catholic was not suitable for public consumption.” Ward remembers Dawkins asking hierarchy in the New Zealand Catholic Church to contact the NZBC to tell them they had no problem with the song.

By June ‘Star Crossed Lovers’ knocked Mary Hopkin from top spot to reach No.1 in New Zealand, completing a trio of chart toppers for producer Dawkins along with Shane’s ‘St Paul’ and The Fourmyula’s ‘Nature’.

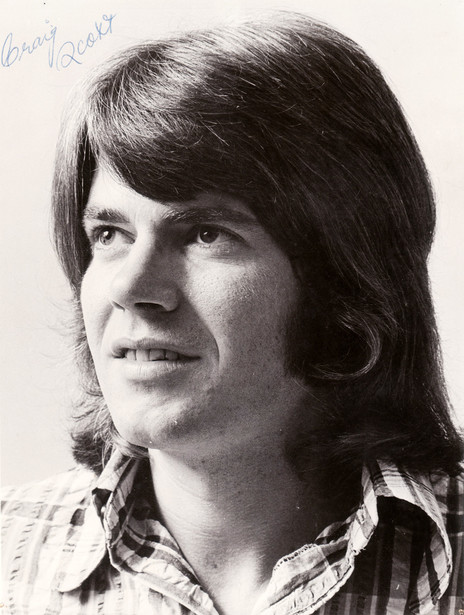

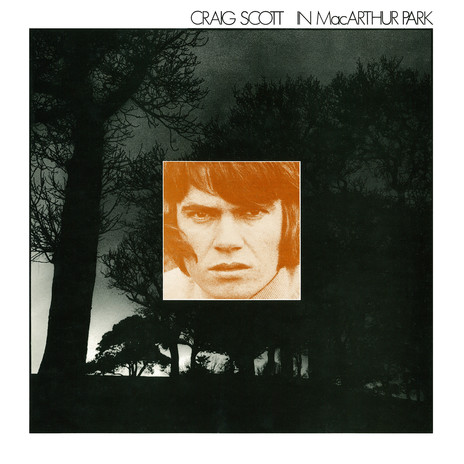

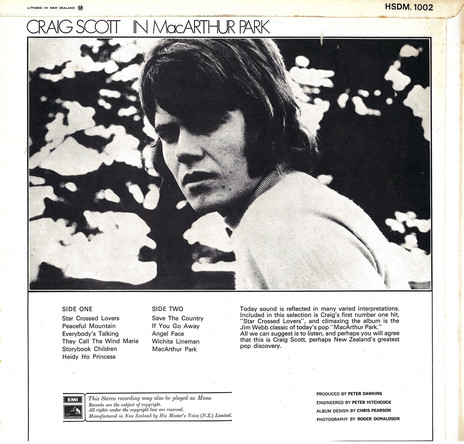

Work was then completed on Scott’s debut album, In MacArthur Park. Featuring a moody cover shot of Scott by future film producer Roger Donaldson, the album included Scott’s interpretations of quality MOR fare such as ‘Wichita Lineman’, ‘Everybody’s Talking’ and Jimmy Webb’s epic title track.

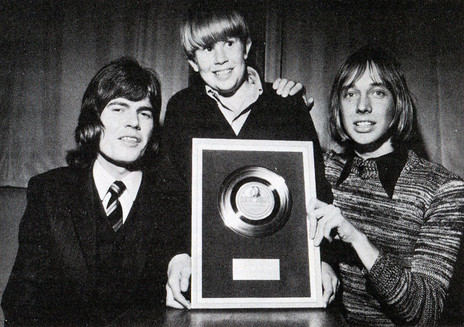

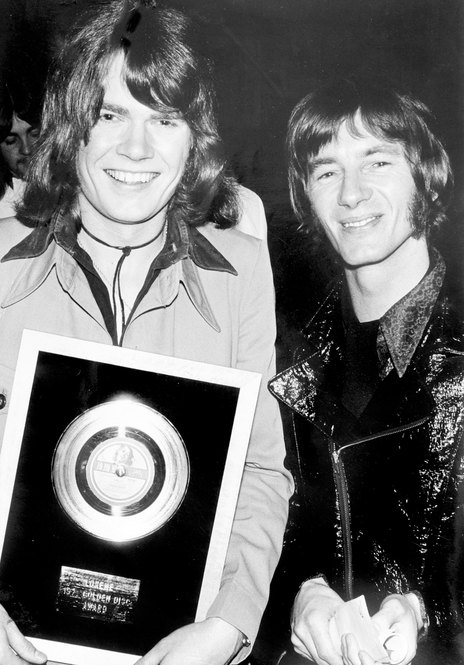

Second single ‘Lets Get A Little Sentimental’ repeated ‘Star Crossed Lovers’ success. It eventually won the 1970 Loxene Golden Disc solo award, the equivalent of today’s Tui for Single of the Year. November’s ceremony, held at the Wellington Town Hall, saw Scott’s single up against the Revival track, also a finalist that year.

Scott made his live solo debut at Teensville Lower Hutt’s first birthday, supported by Creation and Next of Kin; he played to a small but raucous audience with a pick-up band that played from music charts prepared by Garth Young and Don Richardson. The year was rounded off with a “beach tour” taking in Gisborne, Tauranga, Napier, Opunake and Ohope.

In March 1971 Scott travelled to Australia for television appearances in Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Scott’s heart wasn’t in it however, always maintaining in interviews that he was a proud Kiwi and happy enough with success in New Zealand.

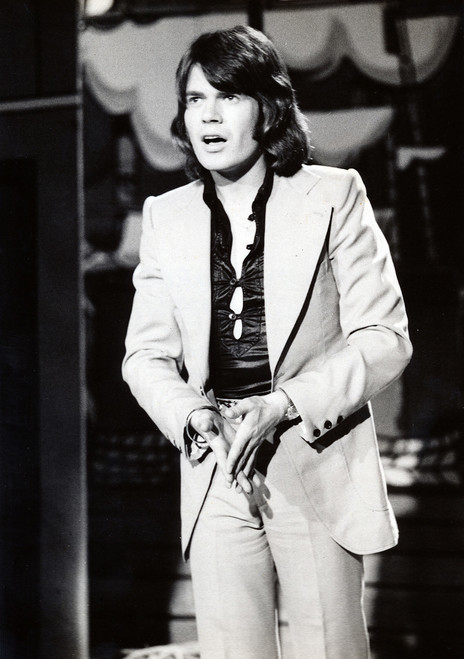

Signing with the Benny Levin agency, Scott took on Russell Clark as his manager. Clark was quick to realise that television was the quickest way to grow Scott’s appeal and secured him a residency on the new Happen Inn programme, the successor to C’mon. To enable the filming of Happen Inn, Scott shifted from Wellington to Auckland’s Herne Bay. Weekly exposure to a nationwide audience skyrocketed Scott’s popularity: until mid-1975 New Zealand only had one TV channel.

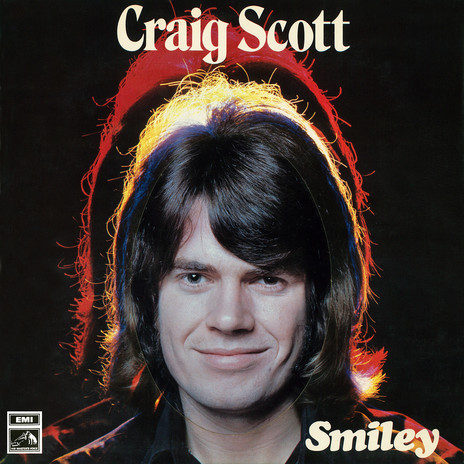

Released on 13 June 1971, ‘Smiley’ dominated the airwaves and gave Scott yet another No.1 hit.

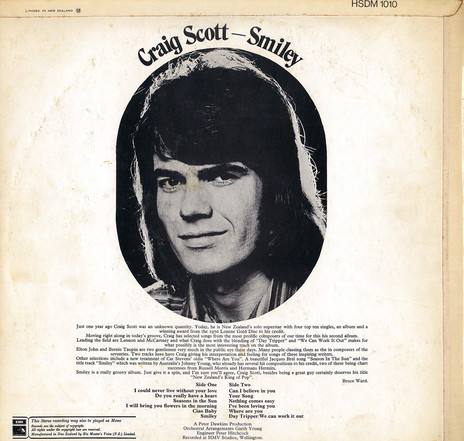

Singles ‘Peaceful Mountain’ and ‘Can I Believe In You’ maintained Scott’s hit run, but it was with fifth single ‘Smiley’ that Scott reached peak fame. Coinciding with the launch of Happen Inn and released on 13 June 1971, ‘Smiley’ dominated the airwaves and provided Scott with yet another hit, charting at No.3. Written by Australian Johnny Young about a young Vietnam soldier, ‘Smiley’ became one of the biggest hits of the 70s in New Zealand. A music video was filmed for the track, which is now believed lost, though outtakes can be seen at NZ On Screen.

The single repeated Scott’s Loxene Golden Disc success, taking out the prizes for solo artist and single of the year at that year’s event, held in Palmerston North in November. In addition to the trophy Scott won the princely sum of $750 – the equivalent of $10,000 today. Dawkins won the prize for best producer.

‘Smiley’ also became the title of Scott’s second album, which featured an expensive-to-produce die-cut cover and included his next hit, ‘Ciao Baby’. By now Scott was well and truly a household name.

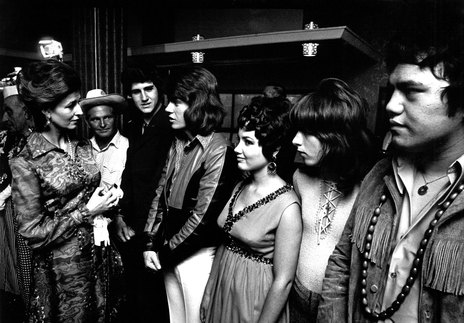

Despite this, and perhaps indicative of the entrenched attitudes of the time – that New Zealand artists simply weren’t as good as those from overseas – major live appearances for Scott still tended to be as a support act. In September Scott, along with The Rumour and Vaughan Lawrence, supported Cilla Black on a nationwide tour promoted by Christopher Cambridge. A 20-piece orchestra comprising Happen Inn players supplied backing music for all the artists.

In an interview with Len Chamberlayne of the Sunday Times in November 1971 Scott noted that he’d had to move flats three times due to fans discovering where he lived. “It was literally impossible to walk down the street without being recognised and often as not, screamed at,” he said. Jo, Scott’s hometown girlfriend since the 60s, joined him in Auckland, keeping him sane amid the overwhelming public glare, and running his fan club incognito on the side.

On December 1, Scott – along with Tramline and The Lydon Sisters – played a show for prisoners at Mt Eden jail at the request of the Rev. A. R. Cooper. Summer saw another beach tour – The BioClear Gold Disc Stage Show, which had Scott and Bunny Walters playing shows in New Plymouth, Napier, Auckland, Tauranga, Mt. Maunganui, and Gisborne into January 1972.

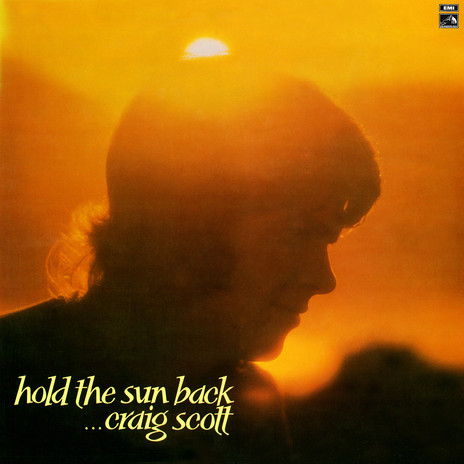

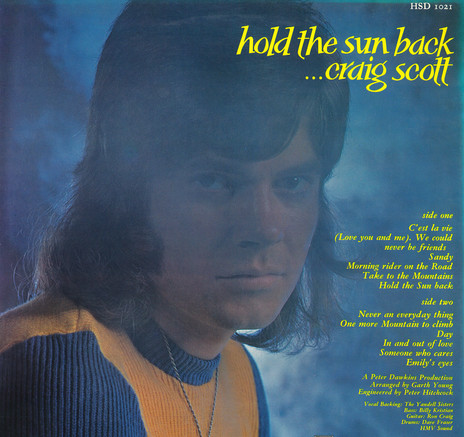

Featuring yet more hit singles in ‘C’est La Vie’, ‘Sandy’, and ‘One More Mountain To Climb’, Scott’s third album, Hold The Sun Back, was to be the last overseen by Dawkins. The fabulously successful working relationship with Scott came to an end when the producer moved to Sydney in 1972.

Scott’s tandem careers as a pop and television star saw him head off Yolande Gibson and Bunny Walters to pick up the Entertainer of The Year award at Trillo’s in October 1972. The following summer saw a huge Happen Inn tour take in 29 shows at 31 different venues, following in the tradition of earlier C’mon tours. Accompanying Scott were Beam, Bobby Davis, Beverley Lee and host Peter Sinclair.

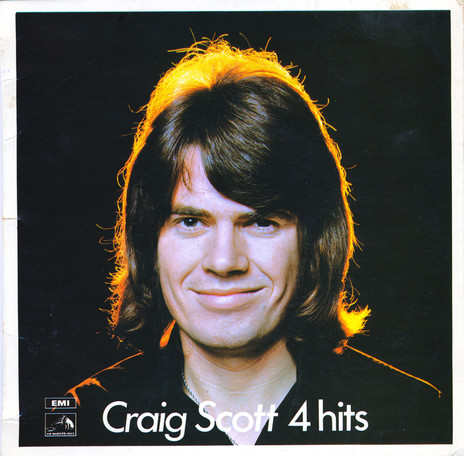

At EMI, a second singer/producer partnership developed with Alan Galbraith in 1973, when Galbraith returned from England to become EMI house producer. Galbraith picked up where Dawkins left off and the hits kept on coming. Galbraith used his connections with publishers to find songs that suited Scott’s style. ‘When Jo Jo Runs’, ‘Wind and Rain’, ‘Rock and Roll (I Gave You All The Best Years Of My Life)’, ‘Durango’ and ‘Fingers and Thumbs’ continued a non-stop succession of hits through 1973 and 1974.

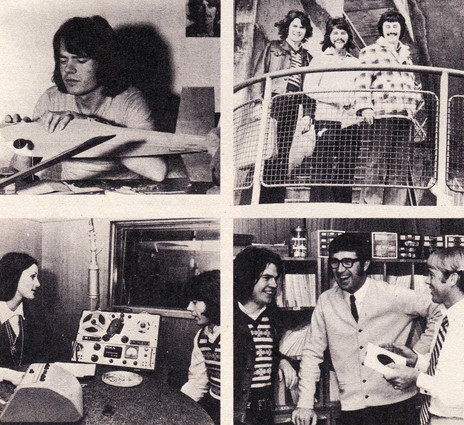

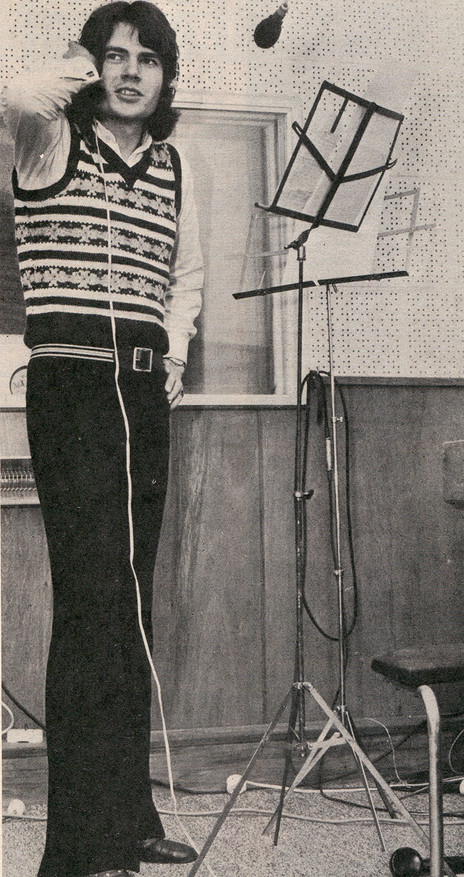

In February 1973 Scott married his childhood sweetheart Jo in Dunedin. Film cameras were present along with hordes of fans, filming as part of a TV special. Profile: Craig Scott aired at primetime, 6.30pm on 12 August 1973. It included wedding footage and recording sessions for his latest single. The special traced Scott’s career and included interviews with his mother, wife Jo, producer Alan Galbraith, engineer Peter Hitchcock, manager Russell Clark and musical arranger Garth Young.

Scott’s professionalism in the recording studio was reflected in his reliability in front of the TV camera. In a parallel to his relationship with Dawkins and Galbraith, Scott found himself working regularly with Kevan Moore and later, Christopher Bourn, both legendarily hard taskmasters. TV work gradually overtook his recording career, as Scott became a mainstay of the programmes Happen Inn (three seasons), Sing (two seasons), and Radio Times (1980-83). The schedule for 1973 set the template for the next three years: 13 or 26-week TV seasons punctuated with one-off shows and awards ceremonies.

But by the end of 1976, after a two-week season of live shows in Caroline Bay, Timaru, Scott had had enough. The demanding and relentless pressure of show business saw him make a conscious decision to step away from recording and performing altogether.

Scott teamed up with Mike Corless to form New Music Management in March 1979.

Moving to Auckland’s North Shore, he and Jo started a family and opened a successful café in Takapuna. It provided a complete change of lifestyle for Scott, and one that he enjoyed. In an interview for the New Zealand Herald in December 1978, Scott reported completing “an exhausting 18 months of cutting sandwiches”.

Following the sale of the café, Scott teamed up with Mike Corless to form New Music Management in March 1979, with the aim of establishing a viable touring circuit for local artists. They were soon joined by Russell Clark and Benny Levin who added international tours to the mix. Scott recalls one of the highlights of his time at NMM was tour-managing Toy Love. “I was pretty nervous thinking these young punks might have an ‘attitude’ towards me with my background but in fact we got along really well, and the tour was a huge success.”

The early 80s saw the arrival of home video in New Zealand, with Russell Clark playing a pioneering role in establishing the local market. Leaving NMM, Clark and Scott established a VHS distribution and rental company. Contacts made in the industry lead to Scott eventually spending 15 years from the mid-80s running Warner Home Video during the boom years of VHS and DVD rental and sales.

Scott left Auckland in 2001 to return to his beloved South Island. Initially he settled in hometown Dunedin, before a move into the real estate business in Arrowtown, where he now lives.

Despite stepping away from the music business 40 years ago Scott says that hardly a day goes by without members of the public coming up to tell him, “I had a poster of you on my wall as a teenager,” and ask if he’s still singing. “The answer is always no,” he smiles. “I don’t think I could reach the high notes anymore.”

--

Read more: Craig Scott in Playdate, 1970