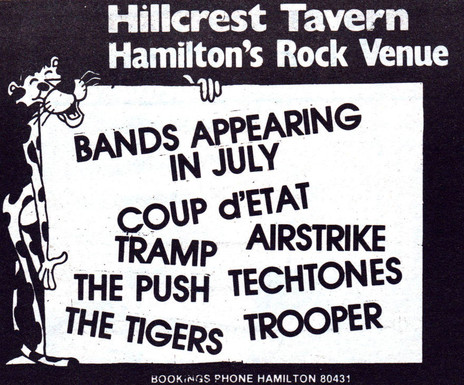

From December 1979, when they left Invercargill to start their first national tour, until the line-up disbanded in July 1981, Airstrike honed their considerable skills and stagecraft while relentlessly working the lucrative North Island pub circuit. The Hillcrest Tavern in Hamilton and Cabana in Napier became favourite hunting grounds for this young and dynamic band.

The circuit allowed bands to tour New Zealand fulltime, often taking up six-day residencies at a venue before moving on to the next on a Sunday. In 1980 alone, Airstrike played more than 250 gigs.

In that brief time they transformed from playing crowd-pleasing covers to original rock songs. Airstrike never recorded anything more than self-funded demos in New Zealand. A major-label recording contract came several years and line-up changes later in Sydney when, under the name Kamsha, they released three singles for PolyGram Records.

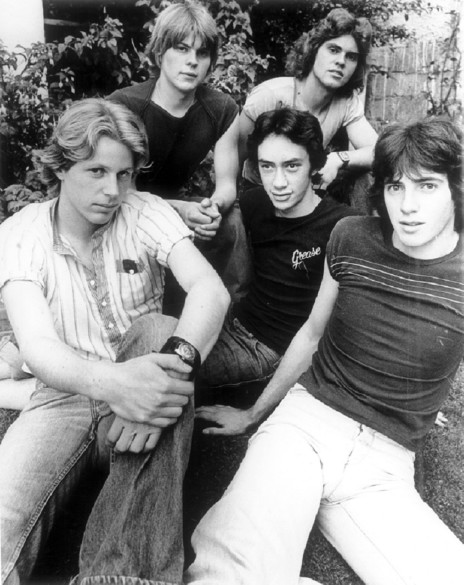

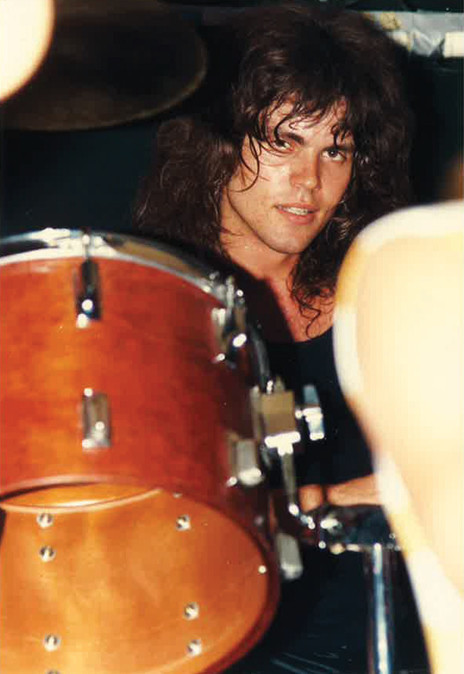

Airstrike began in Invercargill in 1975 as a fresh-faced James Hargest College band, Blue Wagon, with the Chilton brothers – Neil on lead vocals and rhythm guitar, Peter on drums – and their cousin Russell Hubber on bass and Craig McKenna on keyboards. The name lasted just one gig before they changed it to Prediction. They were legally too young to play in pubs, so most of their gigs were private jobs – weddings, hall parties, corporate events and the like – and they played a lot of them.

With three members called Neil, nicknames became obligatory.

Eventually Hubber and McKenna were replaced by Neil Burns (bass) and Neil Sutherland (keyboards) and the band changed their name again, to Tarbet, which they remained for the next three years.

With a disproportionate number of Neils in the band, nicknames became obligatory. Neil Chilton was “Wally” (after his middle name Wallace), Neil Burns was “Burnsy” and Neil Sutherland became “Sutho”.

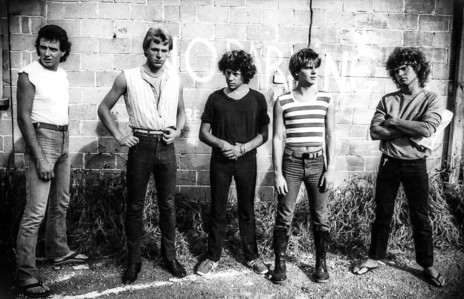

The line-up crystallised in early 1979 when the technically proficient Graham Moses was recruited on lead guitar.

Not long afterwards the young, energetic band came to the attention of national promoter Benny Levin, who had just formed New Music Management (NMM) with other luminaries: singer Craig Scott, promoter Russell Clark, and booking agent Mike Corless.

At the recommendation of Invercargill promoter and musician Danny Johnson, Levin – who was touring with Golden Harvest – came south to Invercargill to see what all the fuss was about. Although they were still strictly a covers band at this point, Levin was impressed.

Witnesses in the crowd that night at the old Southland Musicians Club in Deveron Street report that, after Tarbet’s smoking set, Levin got up on stage and informed the crowd that he was going to take this band to Auckland. There was one proviso: the name Tarbet had to go. Levin suggested Airstrike, and just before they left Invercargill that became their name.

In December 1979 Airstrike stepped into their tour bus and headed north. They played gigs booked by Levin all the way from the Rosebank Lodge in Balclutha to their new base in Auckland, where they joined NMM’s growing stable of bands.

Airstrike were met at Framptons in Hamilton by Benny, who had driven down from Auckland in his Mercedes to see the band. He was excited to see his young charges again but told them they needed to start writing original material, which they duly did, the first being a song called ‘Motels’.

Peter Chilton recalls: “Sutho and Wally would just stand around the piano and write in the bar during the day. The band would go down later on and we’d play it, and then we’d play it that night. The songs developed by playing them live.

“Because we were playing virtually every night of the week [except] maybe Sunday, writing every day, we started filling up with originals.” In a few months Airstrike’s set list featured 90 percent original material.

At their own expense, the band recorded demos of some of their songs at Mandrill Studios in Auckland, with Bruce Lynch engineering. Although the tapes never led to a recording contract they did lead to Airstrike crossing the Tasman a year later to take on Australia.

Meanwhile, Benny had the band flatting in a house in Manukau. Although they were playing a lot of gigs around Auckland, often supporting their NMM stablemates, they were still developing their own sound and style. Benny was impatient to raise Airstrike’s profile, and Peter Chilton recalls that one disastrous gig in front of an influential audience at Kicks Nightclub on Auckland’s North Shore soured their relationship.

“That gig where we supported Flight X7 was one of the worst gigs I ever played. It was all industry people, record company people, all their crowd.

“They played first, then they got on the piss. Then we came on. Our first song was just horrible. I don’t think they booed but I wouldn’t have been surprised.

“We hated it. We said to Benny, ‘what the fuck were you thinking putting us there?’

“He meant well. He was just trying to break us into the Auckland scene but we probably weren’t ready for it.

“Being in a young band getting exposure like we were you have to grow in public. You make mistakes. You’re going to make some bad choices. Not everything is going to be pretty.”

The band and Benny continued to have disagreements about Airstrike’s direction and after just three months they parted company in March 1980 and took on Hamilton-based promoter Chris Cole as their booking agent. They’d met Cole several months earlier and hit it off instantly. Cole was placing bands on the DB pub circuit and the members of Airstrike embraced their new rock ’n’ roll lifestyle to the fullest extent that a bunch of good-looking young lads from Invercargill can muster.

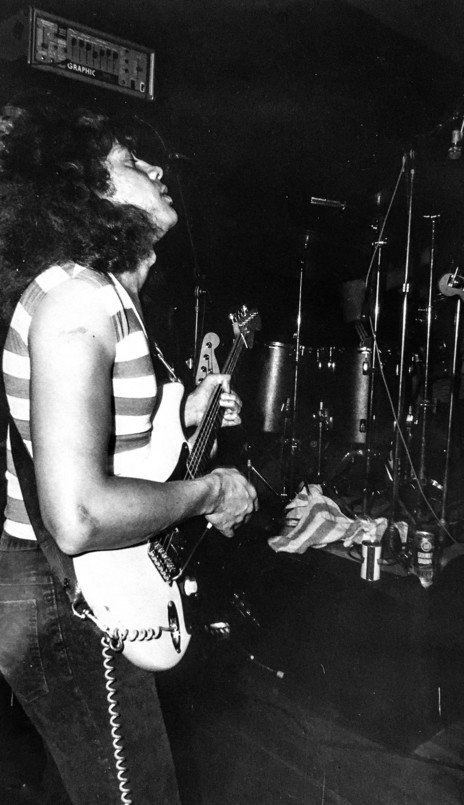

Well, not all of Airstrike did. Guitarist Graham Moses was over it and wanted out. The flamboyantly talented Paul Maaka replaced him immediately in July 1980, bringing extra rock star cred to the band’s already highly visual stage act. Things were coming together for Airstrike, much of it attributable to Chris Cole.

He proved to be a huge champion of the band, getting them lucrative gigs, hawking their demo tapes to record companies and eventually joining them when the band relocated to Sydney in 1981. It was at Cole’s instigation that Hello Sailor frontman Graham Brazier was brought in to produce some more demos at Mandrill Studios.

Airstrike was filling big venues at least three nights a week and doing all right, thanks very much.

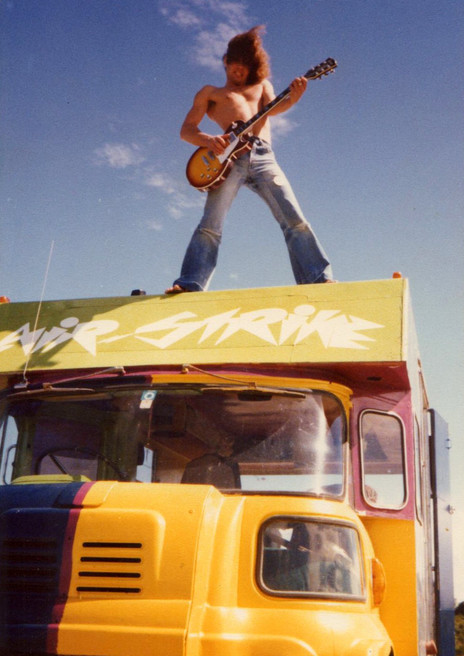

Between their pub residencies Cole would put Airstrike into other plum gigs. One of them was the final Nambassa Festival near Waihi in 1981, where they joined an eclectic line-up that included John Mayall, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, the Charlie Daniels Band, and The Topp Twins.

“We really wanted Sweetwaters, but Chris came back and said ‘I couldn’t get Sweetwaters but you’ve got Nambassa’,’’ Peter Chilton says.

“There were all sorts of weird dynamics going on in the tent between the American white and black bands.”

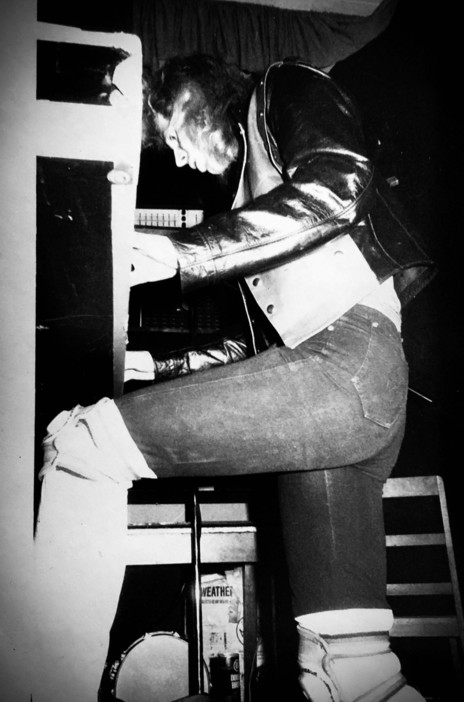

Airstrike, meanwhile, were filling big venues at least three nights a week and doing all right, thanks very much. They had quickly developed their stage show, and their sound system, to epic proportions. They were hiring one of the more expensive rigs in New Zealand at the time, a Cerwin-Vega PA system from Oceania Audio, and with the premium sound gear they were getting next-level loud.

“We had VH36 bins, two a side, with W bins under each … they were lean and mean and just punchy. I had another VH36 as my sidefill,” Chilton says. “That’s why I’m fucking deaf.”

They’d also recently “stolen” roadie Chris Simmonds off Kevin Stanton’s prog-rock band Think, and he ran an impressive light show. Simmonds became a long-term member of the Airstrike crew, with the nickname “Super Roadie”.

Many of the pubs on the circuit were in residential areas, and noise control was rapidly becoming an issue for bands including Airstrike.

“As the bands got louder they started putting noise meters in everywhere. We couldn’t handle the noise meters. We had to play a loud show. That’s what the punters came for.”

The noise meters had a trigger that cut power to the PA system if the volume rose above the limit, so bands would always have to keep an eye on the system warning lights to make sure they didn’t go red.

Bass player Neil Burns, who’d given up an electrical apprenticeship to tour with Airstrike, became adept at hotwiring noise meters so they wouldn’t trip the power out, allowing the band to continue blazing well over the 100 decibels mark.

Bass player Neil Burns became adept at hotwiring noise meters in pubs so they wouldn’t cut the power.

Chilton recalls a riot almost happening in the packed and pulsing West Town pub in New Plymouth pub when the bar manager, realising the band had bypassed the noise meter circuit, turned the three-phase power off on Airstrike mid-song, momentarily plunging the room into darkness and silence.

“I can still see him running up and down the side of the bar trying to figure it out. Then he pulled the plug and said ‘you’re sacked’.

“I remember Neil [Chilton] getting up on stage and yelling “we’ve just been sacked for being too loud’ and the place went crazy.”

As well as hotwiring noise meters, Neil Burns took on the role of band creative director. He developed a simple but effective blacked-out stage set using many metres of black polythene and tape, giving the band a clean, stylish professional backdrop that played well with Chris Simmonds’ lighting.

“It took a lot of setting up but we were there for a week so we’d spend the time,’’ Peter Chilton says. “That was Burnsy’s job. We had the tidiest stage. There were no leads visible. Then we’d set the lights and get the smoke machine going. We had a show. That’s why we kind of got a reputation. We didn’t just put out amps on the stage. We really thought about the set-up.”

On their travels Airstrike couldn’t help but notice Knobz stickers plastered all over the towns they played in. The boys from Invercargill saw an opportunity to ride their Dunedin neighbours’ marketing coat-tails.

“The Knobz were fantastic marketers,’’ Chilton says “They weren’t a great band but they were great marketers. Wherever we saw a Knobz sticker, we’d put an Airstrike sticker. All around New Zealand, wherever there was a Knobz sticker, there was an Airstrike sticker … on bus shelters, band rooms, rubbish bins, pub doors, on cars.”

He’s sure that guerrilla marketing campaign helped to raise their band’s profile.

Chris Cole had been busy sending Airstrike’s demo tapes to people in high places. One of them was John Anderson, from CBS Records’ publishing wing April Music, in Sydney. He liked the tape and flew over from Sydney to hear Airstrike play at the Cabana in Napier. After seeing them perform he immediately offered to set them up with the Harbour Agency in Sydney, and strongly suggested they do it.

Righi told them he’d put Airstrike to work straight away. “Just get over here,” he told them.Neil Chilton and Neil Burns flew to Sydney to meet Harbour Agency boss Sam Righi. They played him some live tapes of the band recorded through the sound desk and showed him some promo photos.

AIRSTRIKE SOLD THEIR TRUCK AND ANY GEAR THEY DIDN’T NEED TO TAKE AND HEADED TO SYDNEY.

Airstrike sold their truck and any gear they didn’t need to take and headed to Sydney, where John Anderson had arranged a house for them in Annandale. Super Roadie Simmonds and Chris Cole followed soon after.

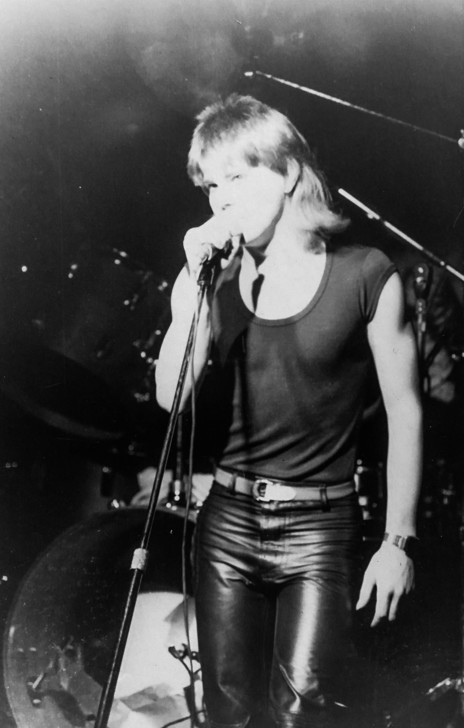

In just 18 dizzying months, Airstrike had transformed from being a covers band playing weddings in Invercargill to an original rock band plying the tough Aussie club circuit and supporting the likes of Australian Crawl, the Divinyls, the Radiators, the Choir Boys and Dragon.

Their first gig in Sydney was at the Mansil Room in Kings Cross in early May 1981 – “one of the dirtiest, rankest little clubs,’’ Chilton says. “The first band went on at midnight and the last one finished at six in the morning.

“It became immediately apparent to us that it was completely different to New Zealand.”

Airstrike found the going tough. Neil Burns had contracted glandular fever and was seriously ill and the band often had to drive miles across Sydney on consecutive nights to dead-end gigs, playing sometimes twice a night.

Airstrike’s arrival in Australia unfortunately coincided with Mushroom boss Michael Gudinski ordering a cleanout of his affiliated companies. Within three gruelling, character-forming months Airstrike were dropped by the Harbour Agency, and eventually, buggered and broke, the band played its final gig at the Astra in July 1981.

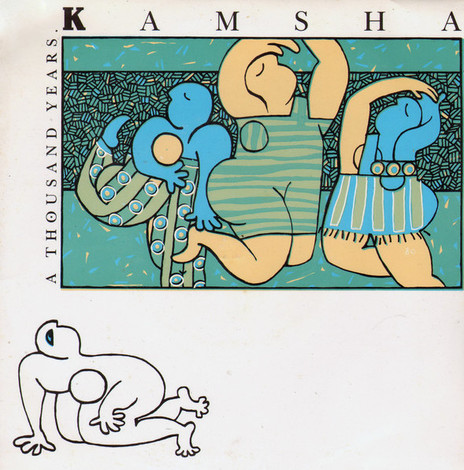

After a year or so of reality holding down day jobs, Neil Chilton, Peter Chilton and Neil Sutherland would reunite in September 1982 in another short-lived band, Strika, before the three joined forces again in 1984 in the most commercially successful band of their careers, Kamsha.

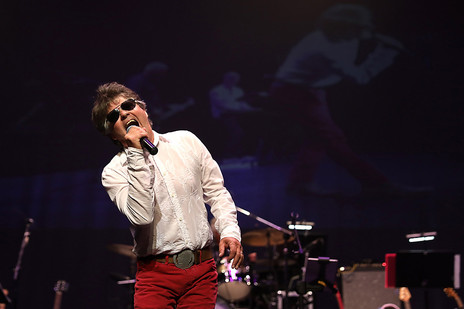

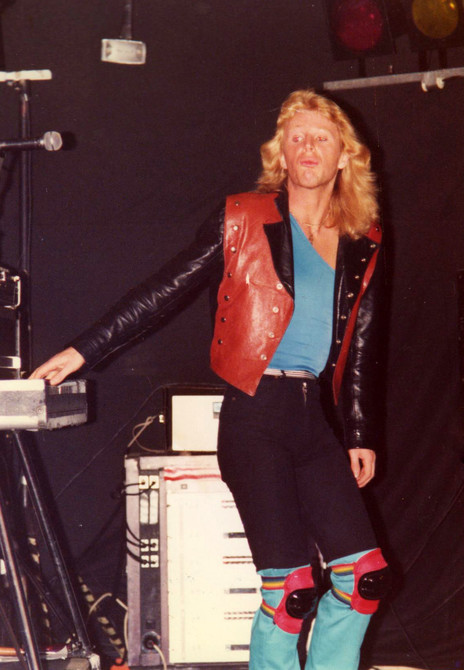

Kamsha were a commercially viable dance-pop band in the mould of Eurogliders and The Models, sporting stylish haircuts, designer clothes and angular jawlines.

Managed again by Airstrike’s former mentor Chris Cole, they signed a great contract with PolyGram Records which demanded three singles and an album.

The band enjoyed some success, touring with Pseudo Echo, Dragon and Australian Crawl, but a change in personnel at PolyGram left them on the outer and despite producing three singles they never got to record the required album.

In fact, Chilton told The Southland Times in 2012, “We were actually fucked right from the start”.

The A&R man who had signed them, Michael Crawley – their most enthusiastic supporter at the record company – was sacked a week after Kamsha came on board and the band never enjoyed PolyGram’s full support after that.

“They put a bean counter in charge of us and that’s where everything went wrong.’’

PolyGram “wanted to pigeonhole us as a hairdresser band”, Chilton says, which never meshed with Kamsha’s hard-rocking live show.

To that end, and looking for a big return on their investment, the record company suits poured buckets of money into producing Kamsha, including spending about $15,000 on their first video, ‘He Will Sleep’.

There’s a video on YouTube of the band performing on TV pop show Countdown. It’s 1980s fashion of the highest order, with the massive rhythmic, cathedral-echo sound exceeded only by the litreage of hairspray required to keep Neil Chilton’s epic quiff in place.

More money was thrown at single two, ‘Work Until You Drop’, which was produced by INXS drummer Jon Farriss and sounds like it.

By the time they released their third and final single, ‘A Thousand Years’ (1985), the video was a budget job, done with a hand-held camera.

“They’d blown so much money on us and never recouped it, they just wanted to ditch us,” Peter Chilton says.

Only problem for PolyGram was the small matter of Chris Cole’s canny contract.

With nothing to lose, Kamsha stood their ground and had legal papers drafted threatening to take PolyGram to court.

With all the oppressive might a multinational record company can muster, PolyGram threatened to drag out the case for years, crippling the members of Kamsha financially.

What PolyGram didn’t know was that regardless of how long court proceedings took, Kamsha’s legal fees would be zero. A lawyer girlfriend of the band’s Australian bass player Wayne Pracey was representing them pro bono, so Kamsha called PolyGram’s bluff.

PolyGram was in breach and knew it, and eventually they settled quietly out of court “with a big handsome cheque for us, which we took,” says Chilton.

What PolyGram didn’t know was that the band’s legal fees would be zero.

Kamsha finished in 1986.

Cole stayed in Sydney and remains a high-profile promoter who has worked with many stellar bands, including U2.

“Super Roadie” Chris Simmonds was the follow spot operator when David Bowie played his Serious Moonlight tour concert at Western Springs, Auckland, in late 1983.

Neil Sutherland established a massively successful recording studio in Sydney where he is an in-demand, multiple APRA award-winning writer of soundtrack music for television and movies. Mythbusters and Border Security are just two of his. He is the most celebrated writer of screen soundtracks in Australian history, with 12 APRA-AMCOS Awards to his name at the time of writing.

Paul Maaka retired from music and lives in New South Wales.

Neil Chilton built a beautiful home in Gibbston Valley, central Otago, and remains a popular solo entertainer.

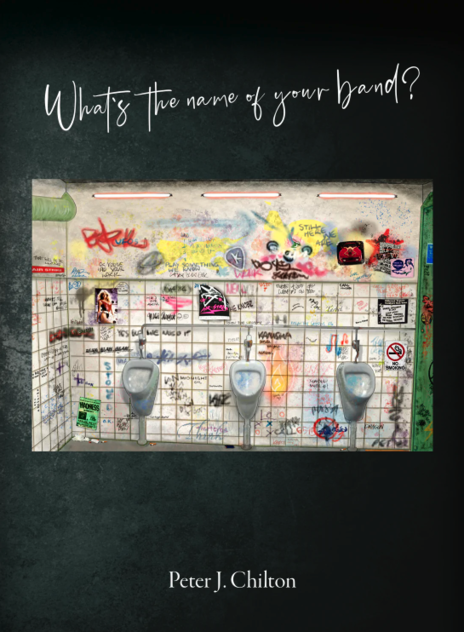

Peter Chilton is writing a book about Airstrike’s colourful career. Its working title is What’s The Name Of Your Band?

Neil Burns passed away in September 1997.

In 2017, 36 years after they broke up, Airstrike reformed to play a one-off set at the ILT Southland Entertainment Awards in Invercargill. They invited former Exponents bass guitarist Dave Gent to join them – and Burnsy’s bass took pride of place in the centre of the stage.

--

Update, 2022: Peter Chilton has written What’s the Name of Your Band?, a warts-and-all memoir of his years with the bands Air Strike, Strika and Kam Sha.