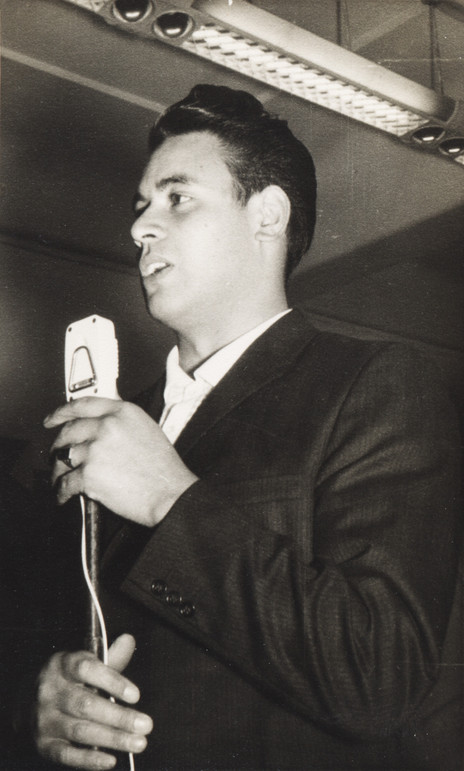

Howard Morrison, born in 1935, had the perfect background to lead the Quartet. His father Temuera had played rugby for the New Zealand Māori team; his mother Kahu was a teenage member of the Rotorua Māori Choir that made historic recordings in 1930. With his powerful tenor, drive and good looks, Morrison was a natural front man.

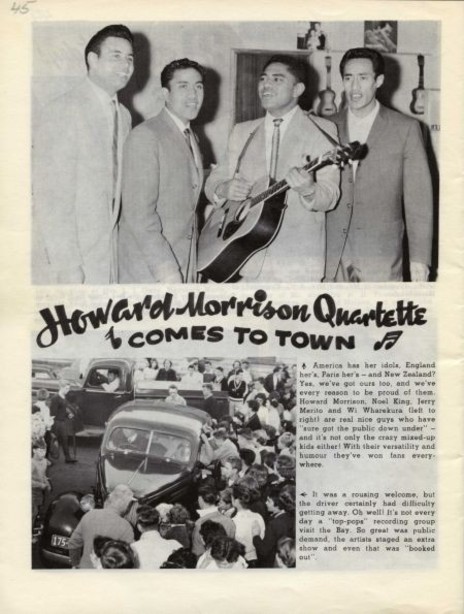

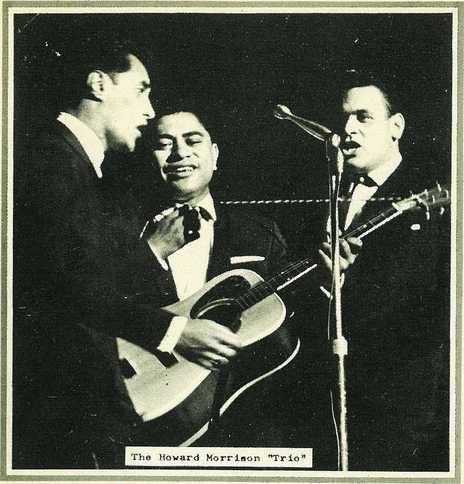

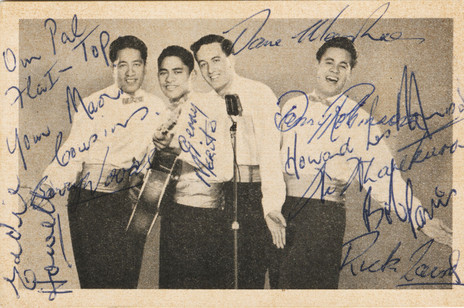

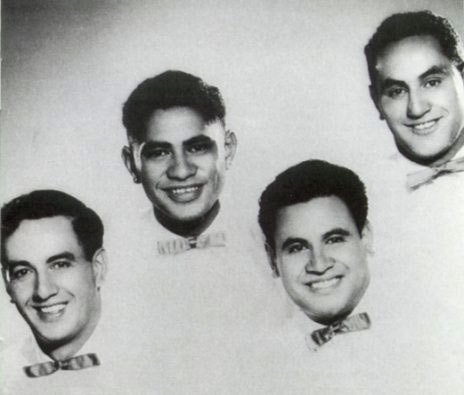

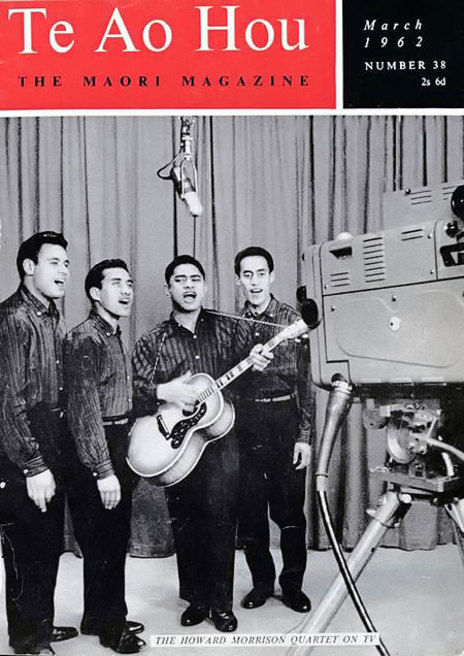

In the most famous line-up of the Quartet, Morrison mostly took the lead vocal. Wi Wharekura sang alto, Noel Kingi the deep bass, and Gerry Merito was the lynchpin: a born comedian with a guitar style that launched countless singalongs. “Gerry was the driving force in harmonies,” said Morrison. “He could go anywhere, take any part; his pitch was absolutely marvellous.” In 2007, Merito praised Morrison’s infectious energy for lifting the group up when they felt lacklustre or were out of sorts. “His voice? Well, I don’t think there was anyone to compare with him in our day. He was out on his own.”

Like Elvis, Morrison could sing anything, and did.

Like Elvis, Morrison could sing anything, and did. As a child in Rotorua and Ruatāhuna, he sang hymns in Māori at church, then over Sunday lunch the extended family would continue with more popular fare. He never forgot the Italian songs learnt from returned soldiers of the Māori Battalion – ‘O Sole Mio’, ‘Come Back to Sorrento’ – and he performed them with remarkable veracity. “I used to call myself Mario Māori Lanza,” he recalled.

While milking the family cows, Morrison would accompany the wholesome pop songs on the Lifebuoy Hit Parade.“I would mimic whoever was singing, male or female. I knew all the hit parade songs by heart. It gave me a sort of subconscious knowledge of what people wanted to listen to. And what the majority of people still want to listen to is middle-of-the-road popular.”

Leaving school at 16, Morrison went to Hastings to work in the Whakatū freezing works; he began singing to entertain his workmates. While singing with a local church choir he met the sisters Isobel and Virginia Whatarau who, with Kahu Pineaha, performed as the Clive Trio: a singing group which recorded for Tanza. When Pineaha left the Clive Trio for a solo career, he was replaced by Morrison.

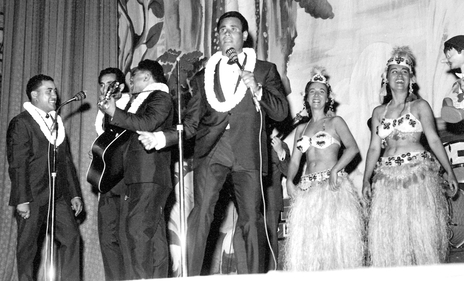

Morrison and the Whatarau sisters joined the Te Awapuni Concert Party, which toured the South Island in 1954. Their concerts mixed traditional and contemporary music. They opened with the singers in piupiu, performing what is now known as kapa haka. The second half featured popular music, with the Clive Trio among the acts: the Whatarau sisters in ballgowns, and Morrison in a tux.

He quickly learnt how to lead a song, to sing harmony, and work out arrangements. He could sing in an eclectic array of styles. Among his influences were The Mills Brothers, The Ink Spots and The Four Aces – and the Italian tenors so beloved by the Māori Battalion.

After his father died in 1954, Morrison returned to Rotorua to live and began performing at rugby socials. He formed a vocal sextet which won the Rotorua Christmas carnival talent quest; among those in the group were his brother Laurie, his cousin John, and Wi Wharekura.

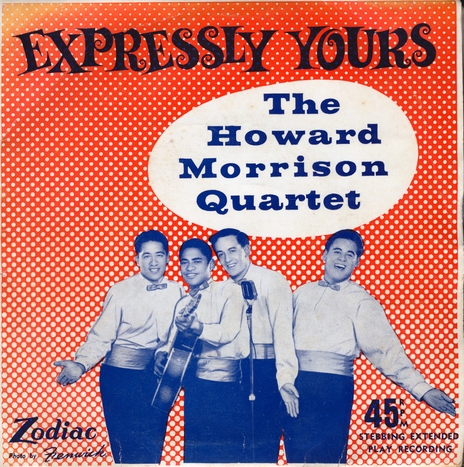

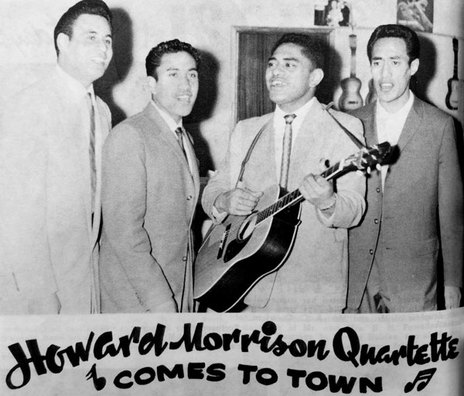

After touring Australia with the Aotearoa Concert Party in 1956, he formed a vocal quartet with Laurie and John Morrison, recruiting another talent-quest winner, Gerry Merito from Taneatua in Te Urewera, to sing and play guitar. Morrison’s mother Kahu, who had been a professional singer, encouraged their pop ambitions. She smartened their look with cummerbunds and bowties, and lined the Quartet up for an inspection in her lounge before they headed out to a performance. She also ensured they didn’t forget the Māori music with which they had grown up.

The Quartet began by performing overseas hits and Māori popular favourites such as ‘Pōkarekare Ana’ and ‘Haere Rā E Hine’, at shows in the Bay of Plenty and Waikato. When Auckland promoter Benny Levin saw them at Rotorua’s Ritz Hotel in 1956, their set included a rock’n’roll medley – just as the controversial genre was starting to explode. He invited them to join a variety show at the Auckland Town Hall.

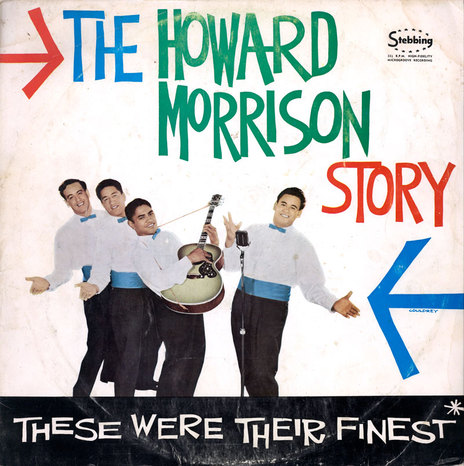

Levin introduced them to Eldred Stebbing, with a view to recording the group. But first, they had to decide on a name. Morrison remembers going through the various options with the group: the Morrison Family, the Ōhinemutu Quartet ... when Stebbing took him aside and said, “Look, you’re the lead, you’re the main man. I suggest you call it the Howard Morrison Quartet. Because if and when the quartet breaks up, there will always be Howard Morrison, entertainer and performer.”

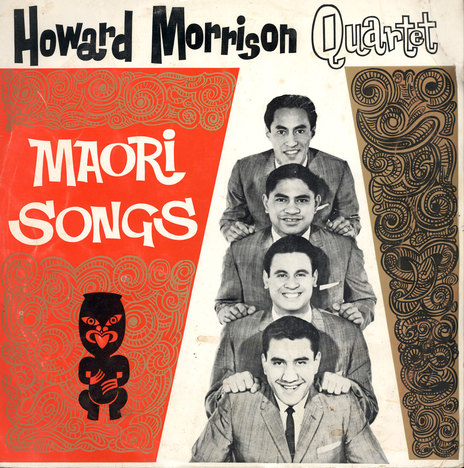

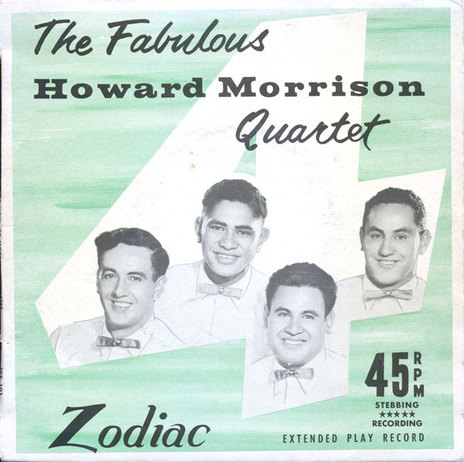

Stebbing took his portable Grundig tape-recorder down to Rotorua and recorded an EP with the newly named Howard Morrison Quartet. The first singles – released on 78s and 45s – were a mix of popular songs and Māori favourites, later recorded at Stebbing’s Saratoga Avenue studio in Auckland. ‘There’s Only One of You’/‘Big Man’ was followed by ‘Hoki Mai/Po Kare Kare Ana’.

‘Hoki Mai’ gave the Quartet its breakthrough hit.

‘Hoki Mai’ gave the Quartet its breakthrough hit. At the end of the Second World War, East Cape songwriter Hēnare Waitoa used the melody of Gene Autry’s country dirge ‘Gold Mine in the Sky’ to create ‘Tomo Mai’, a lament to welcome the Māori troops home to Ruatōria. In turn, the Quartet transformed the song into ‘Hoki Mai’, a spirited, upbeat singalong.

Some Māori were upset that the Quartet had not given the song the respect it deserved for its place in Māori Battalion history, or realised its significance. “At that time I was rather ignorant about the sanctity of the words,” Morrison explained to Caitlin Cherry of RNZ in 2001. “It became a hit because everybody was singing that song at parties before we even recorded it.”

When the original quartet was turning professional, John, a teacher, and Laurie, a civil engineer, decided to remain in steady jobs. Temporary replacements included Tai Eru, Howard’s cousin Terry Morrison, and Eddie Howell. The Quartet’s best known line-up was Morrison, Merito, Wharekura and Kingi, a young bass singer from Rotorua.

Morrison saw the diversity of the group’s material as one of its major assets; they sang standards, Māori favourites, country, pop and Italian songs. Comedy was always central to their act, but their parodies were what made them different – and New Zealand’s biggest stars.

In 1960 ‘The Ballad of the Waikato’, written during a national tour, took them to another level altogether. Merito recalls that he and Morrison were sharing a dressing room before a concert, discussing British skiffle king Lonnie Donegan’s current hit, a cover of Johnny Horton’s ‘Battle of New Orleans’. Eldred Stebbing recorded the song in concert at the Auckland Town Hall, and it was an instant hit, selling over 25,000 copies. ‘The Battle of the Waikato’ captured the humour and crossover appeal of the group; the Howard Morrison Quartet had found its own voice. “We felt we were doing something of our own,” Morrison said the following year. “The words, at least, were original.”

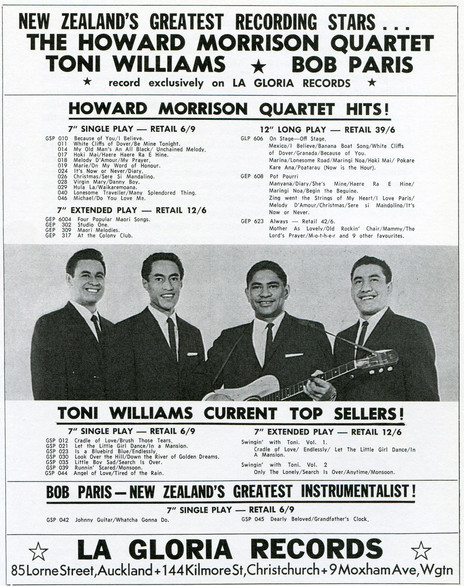

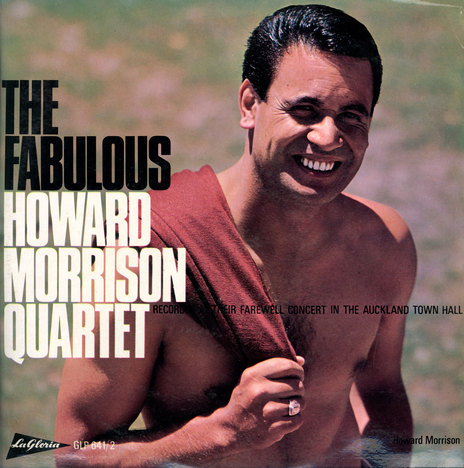

A few months before their success with ‘Waikato’, Morrison walked into a Rotorua store and saw a suave salesman demonstrating his only product: Electromet frypans. Harry Miller told a different story. He remembered seeing the Quartet perform at Bob Sell’s Colony restaurant in Auckland. He moved in with a pitch to manage the band, saying he had a new record company called La Gloria, and offered the Quartet the chance to come in on the ground floor. As his first local artists, they would get his full attention for promotion: he would guarantee the group £2500 worth of work a year. To convince Morrison he was genuine, he signed over the ownership of his shiny, second-hand Jaguar Mark VII.

The Quartet moved to Auckland, with their wives and children. The entrance of Miller also meant the exit of Stebbing and Levin. Miller got the group to re-record ‘The Battle of the Waikato’ and Stebbing sued: not only was it an inferior version, he owned the rights. Miller lost, and thousands of copies of the single on La Gloria were destroyed in the Auckland city incinerator.

Miller thought big. “A cavalcade of New Zealand recording stars” is how a large, outdoor variety show at Western Springs Stadium, Auckland, was advertised. Never before had such a strong line-up of local pop acts shared a stage, and on 24 January 1960 The Howard Morrison Quartet topped the bill; 20,000 people attended.

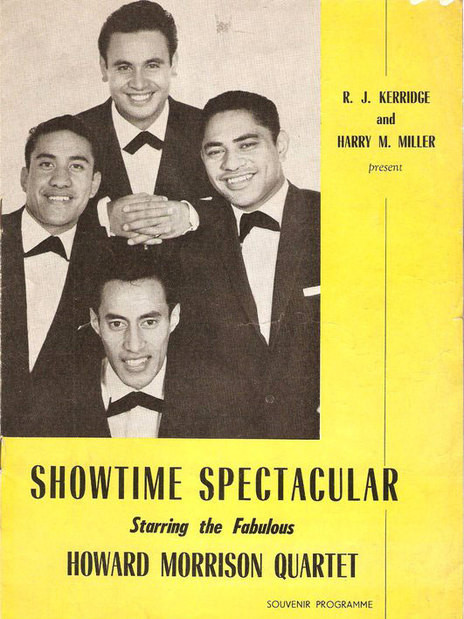

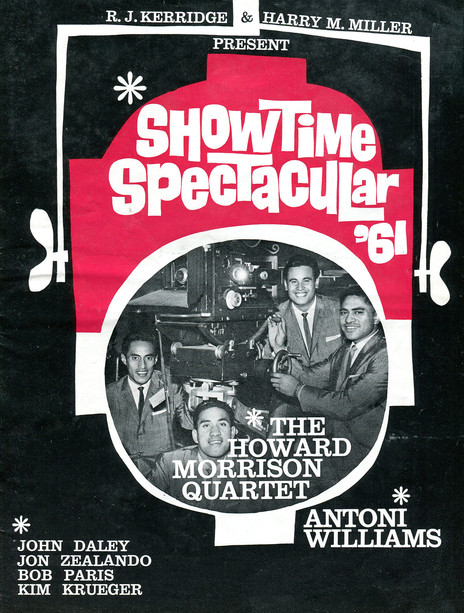

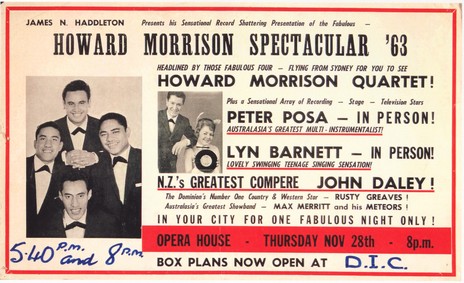

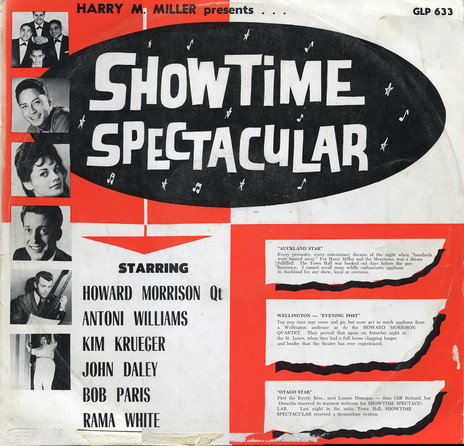

Miller’s next brainwave was to approach the cinema chain Kerridge-Odeon to suggest they go partners in a national tour called the Showtime Spectacular, with the Quartet topping a bill that featured rock’n’roll as well as traditional pop performers. Miller recalled the line-up in his memoir:

“I had a young Rarotongan singer, Antoni Williams, who had immense appeal to women; Patti Brittain, an Australian singer built like a smaller version of Sabrina; Rama White, a Māori version of Tessie O’Shea who sent audiences into hysterics by the way she wobbled her belly when she sang and whom I billed as ‘sixteen stone and a ton of fun’; Noel McKay, a beanpole female impersonator, married to a lady who looked rather like Liberace; Claude Papesch, a blind musician who played tenor sax and piano like a virtuoso; a talented vocal backing group called the Tremellos; and John Daley ... who appeared as compère-comedian.”

Harry Miller was a born promoter who instinctively knew how to coordinate a campaign.

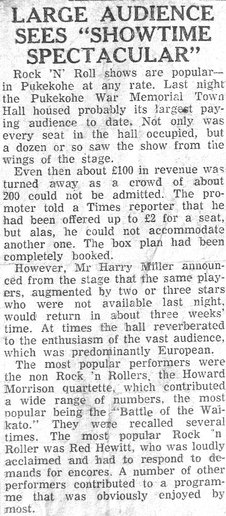

Miller was a born promoter who instinctively knew how to coordinate a campaign. For the first Showtime Spectacular tour, he had everything in place: a hit song, a promotional film clip in picture theatres, a national tour booked, and a sponsorship deal that provided smart stage suits. The Howard Morrison Quartet was reaching a level of popularity unprecedented in New Zealand entertainment. The Showtime Spectacular tour of 1960 was expected to run for five weeks; it lasted for 19.

The hit song was a typically opportunistic idea of Miller’s. In 1959 the All Blacks became embroiled in a controversy about their plan to tour South Africa in 1960: at the request of the host side, there were to be no Māori players in the team. The ‘No Māoris, No Tour’ protests were underway.

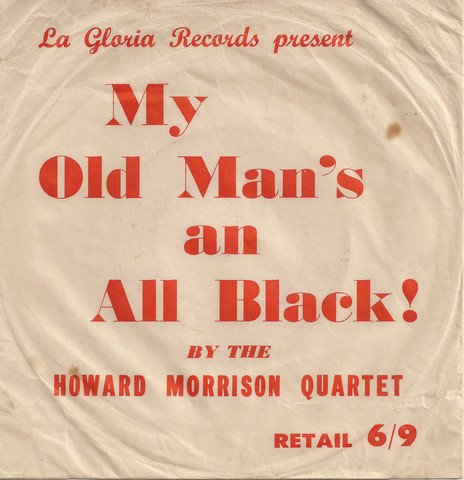

During the Quartet’s 1960 national tour, Lonnie Donegan’s latest hit ‘My Old Man’s a Dustman’ came on the car radio, and a title presented itself to the Miller: ‘My Old Man’s an All Black’. Merito, who wrote most of the words, claimed no political statement was intended and indeed, the barb in the chorus – “fee fee fi fi, fo fo fum, there’s no Horis in that scrum” – was probably lost in the laughter.

The first chance to record it was after the encores at a concert in the Pukekohe Town Hall. Miller allegedly locked the doors so the audience couldn’t leave until a perfect take was performed; it took 11 attempts and two hours. Ten days later, ‘My Old Man’s an All Black’ was in the stores, where it sold 60,000 copies, Miller wrote in his first memoir. “Thank you, Pukekohe.”

Almost overcrowded with talent, the Showtime Spectacular tours became Miller’s cash cow for the next three years. They were, he recalled, “a road show which could do no wrong. I could always rely on it to replenish the coffers.”

The Quartet was on a roll: its concerts sold out nationwide, hit record followed hit record, its promotional films screened in cinemas, and it performed live during the first public television broadcast, on 1 June 1960 (sharing the evening’s line-up with Robin Hood).

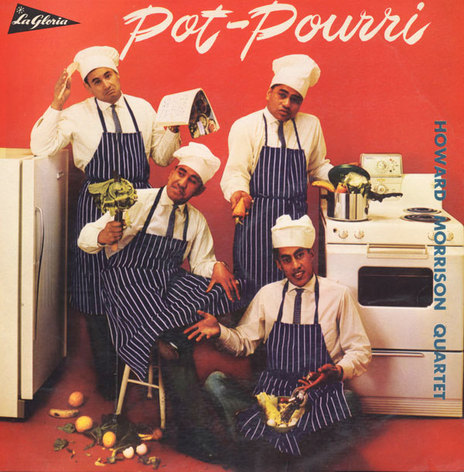

The next four years were a blur of touring, buses, NAC planes, stages, town halls, provincial hotels and many rushed recording sessions. Between 1960 and 1962 they released 28 singles, eight EPs and eight albums on Miller’s La Gloria label. They also ventured to Australia several times, for long tours, and also as support act for tours by the Everly Brothers, the Kingston Trio – and Lonnie Donegan.

Variety was the group’s modus operandi: the hammy humour of old-school variety shows, the eclectic material delivered with sincerity or as a spoof. Corny, cheeky, simultaneously sharp and silly, one legacy of the Quartet was the distinctive mix of comedy and music that became a trademark of the Māori showbands.

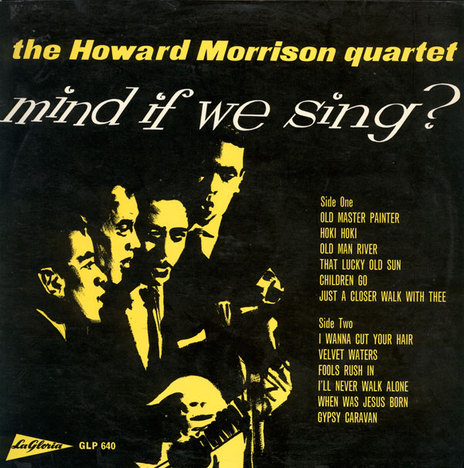

The La Gloria recordings were more primitive than those done by Stebbing for his Zodiac label, but the arrangements became sophisticated thanks to Robert Walton, who in 1960 and 1961 was also musical director and pianist on their tours. When Rim D Paul of The Quin Tikis took over, he encouraged them to bracket their hits as medleys and to vary the harmonies.

The evolution of the Quartet can be seen in the songs they chose to perform and record.

The evolution of the Quartet can be seen in the songs they chose to perform and record. At first, their audience expected covers of overseas hits, and Māori popular favourites. Of the latter, ‘Pōkarekare Ana’ was more Mills Brothers than Everly Brothers, ‘Hoki Mai’ the ultimate singalong, and ‘Haere Rā E Hine’ was played straight. Otherwise, perennials such as ‘Marie’ and ‘Deep Purple’ were intermingled with country (‘Sixteen Tons’, ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds’, ‘Ghost Riders in the Sky’), Italian-style pop (‘It’s Now or Never’, ‘My Prayer’), standards (‘Begin the Beguine’, ‘I Love Paris’), spirituals (‘When Was Jesus Born’, ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’), light R&B (‘Gum Drop’, ‘Short Fat Fanny’), English and Irish pop (‘White Cliffs of Dover’, ‘Danny Boy’) and earnest coffee-house folk (‘Michael Row the Boat’, ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’). There was even an album for mothers, called Always.

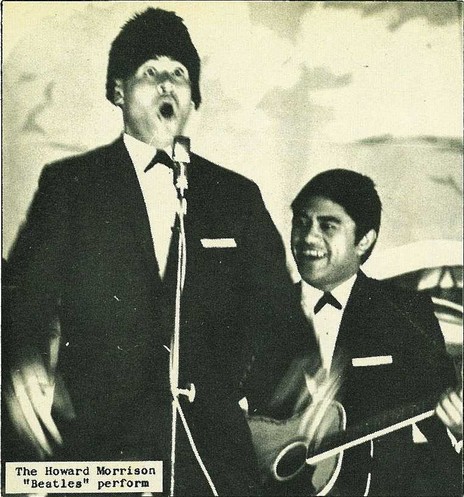

And always there was humour, at first as spoofs or impressions: ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,’ as sung by the Splatters; ‘Because of You’ with walk-on parts by Jimmy Cagney, James Stewart, Jerry Lewis, and the Inkspots. “You’ve heard of Johnnie “Cry Baby” Ray? Here’s the Māori Stingray ...”

‘Mori the Hori’ turned out to be one parody too many; written by Morrison, the others recorded it reluctantly; it was a joke re-fried, with inferior lyrics. Eventually, Morrison began to share the role of lead vocalist with the others, which “probably staved off a passive revolt within the group ... they’d become a bit tired of being backing singers.”

But their bonds were strong. Behind the scenes, a private language developed amongst the Quartet, evolving from techniques learnt from New Zealand magician Jon Zealando. As their support act, Zealando used to make his ventriloquist’s doll speak without moving his lips, and the Quartet copied him from the side of the stage. Boy became doy: Hello doy – hello boy. Cher! – that’s good! Twer meant a woman, from “her”; “heed” or “sheed” meant a man or woman was worth talking to, “heed not” meant don’t get involved. Road-weary New Zealand musicians use these expressions to this day.

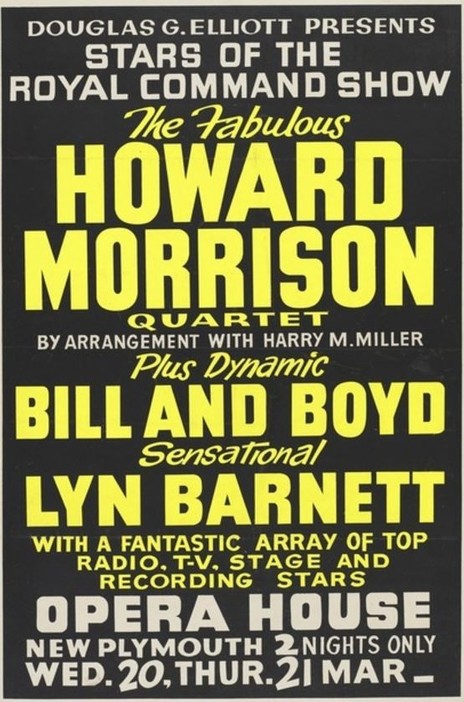

At a 1963 appearance in front of the Queen at a Royal Command Performance in Dunedin, Morrison met the veteran South Island promoter Joe Brown. When the Quartet parted company with Miller, the old-school, family oriented Brown became their new manager, in a handshake agreement.

But they were running out of challenges and, with the big entourages on the Miss New Zealand tours – a busload of beauties, plus the Quartet and other acts – their families could no longer accompany them.

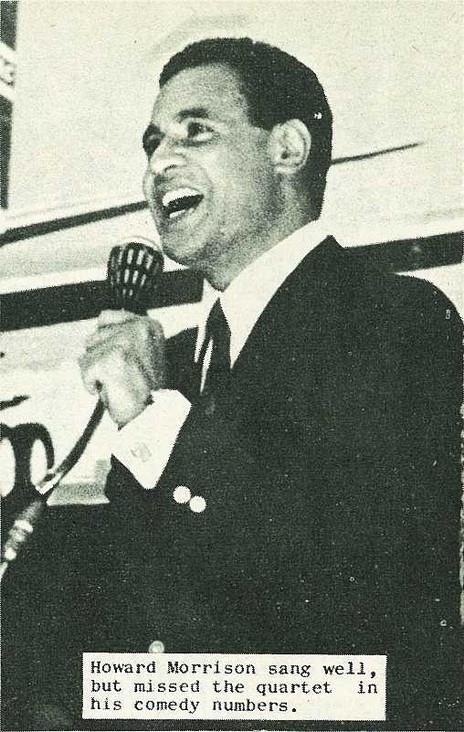

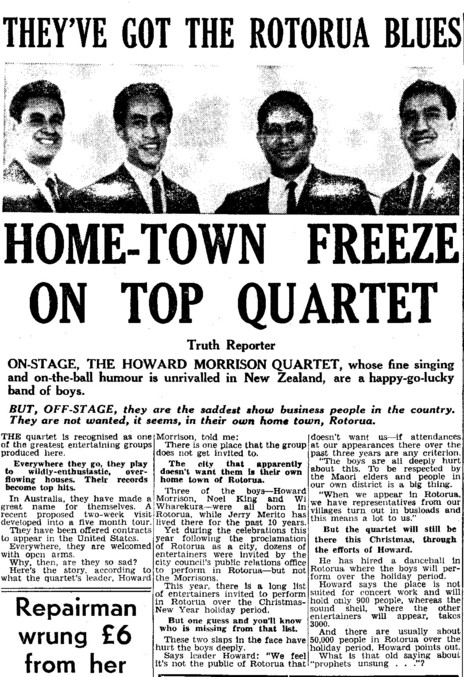

The final tour of the Howard Morrison Quartet in late 1964 was a huge event, “like a long, on-going party,” recalled Morrison. Also on the bill were Toni Williams, Anne and Jimmy Murphy, the Nick Smith Combo and Jim McNaught. At the final Auckland show on 9 December the Town Hall was “packed to the gunnels”. The mayor Sir Dove Myer-Robinson came on stage and said the Quartet’s break-up was an “unnatural disaster.”

Morrison was stunned by the occasion. “People stood up and cheered. There were tears from the audience. Not from us, of course, we’re professionals. We just had to blow our noses a few times on our shirt sleeves.” The Quartet’s last concert was in Rotorua a month later: hometown, but a place where they sometimes felt taken for granted. “It wasn’t a goose-bump show,” said Morrison, “it was just a show.”

Immediately after the Quartet broke up, while Morrison embarked on his hugely successful solo career, the other members briefly toured Northland as a trio; among the support acts were Ian Saxon and Kim Krueger, and the promoter was Benny Levin.

There were several brief Quartet reunions, for one-off events including a TV special in 1975 (the tape was accidentally erased); a profile-raising concert for Morrison’s Tu Tangata (Stand Tall) schools campaign in 1979; and other “reunions” in which guests such as Toni Williams or Rim D Paul filled in for absentees. But from 1965 the members of the Quartet mostly went their separate ways; Morrison’s solo career took him to new levels of fame and responsibility, Merito and Wharekura also kept performing, in New Zealand and Australia.

In July 2019 Wharekura passed away; tall, slim, educated and quietly spoken, he was the last surviving member of the classic line-up of the Quartet. Kingi had died in 1992, Merito and Morrison in 2009.

DALVANIUS said that TO MĀORI, the quartet were “mega heroes”

For decades, the Quartet’s legacy would be felt by New Zealand music, entertainment – and society. Morrison was later rueful that “in pursuit of the market” the Quartet’s “respect for the language and the culture wasn’t always what it should have been”. But in his 2001 RNZ interview – 40 years after their heyday – he could see there was also much to be proud of: the Quartet pioneered so many areas of the music industry. And it was “accepted nationally, without being branded as The Howard Morrison Quartet: Māori. It was just the Howard Morrison Quartet, embraced by the people of New Zealand. And we were able to bring Māori culture to the white, Pākehā majority. So the Māori part of us, we didn’t have to beat our chests about. It just came out naturally.”

‘The Battle of the Waikato’ and ‘My Old Man’s an All Black’ are like time capsules, curiosities from an era when Truth newspaper could run a page of Māori jokes beside a campaign against racial prejudice. But a young Taranaki music fan and aspirant singer who saw them perform often in the Showtime Spectaculars understood their significance to Māori. The Quartet were “incredible entertainers,” said Dalvanius Prime in 2000. “Māori had their mega heroes. But the thing about the Quartet was there were all these Pākehā people getting into it as well. Here were Māori, singing in Māori, to a huge mainstream audience.”

--

Adapted and abridged from Blue Smoke: the Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music, 1918-1964 (AUP, 2010), and the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography entry on Howard Morrison, both by Chris Bourke. Thanks to Caitlin Cherry of RNZ.