Brown was the likely lad, the Southlander who elbowed local entertainment from the age of crackling radio in mahogany cabinets into the national TV spotlight, from sedate ballroom dancing to slicked-back, leopard-skinned rock’n’roll and beyond. A natural entrepreneur who sold fruit and veges from a bicycle during the Depression, he ended up a self-made business tycoon and racehorse owner.

Born in Naseby, Central Otago in 1907, Andrew Joseph Francis Brown was the son of a poor gold miner. Rugby, not school, was an early passion and his involvement in show business came at the age of nine when he raised funds for the team he captained. The school headmaster wouldn’t let the team hire a bus to take them to a tournament, so Brown organised a dance. He advertised a “grand dance” with a popular band, cut up shoe boxes to use the cardboard for tickets, and hired a pianist and violinist. It was a sell-out (and the team did well at the tournament).

And it was on the rugby field that his life changed: as a teenager, he was the victim of a two-way rugby tackle that almost severed his spine. This left him with a permanent stoop.

Like many others, Brown lost his job – motor mechanic – during the bitter Depression years, forcing him to take odd jobs until he discovered his talent as a driving instructor, running a “static school” from a car on blocks to save petrol. But the punters stayed away, so he formed the Single Profit Fruit Company, travelling door to door selling produce until he went broke in 1934.

Over a few days he gathered enough rabbit skins to stage the dance.

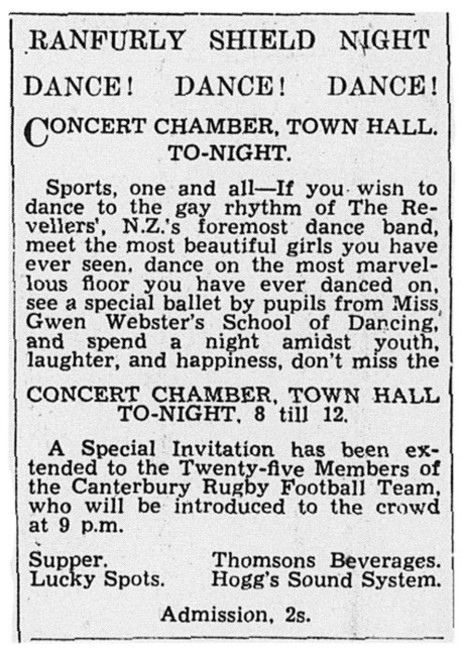

As Labour’s election in 1935 heralded the end of the “grey years”, Brown sensed profit in providing some badly needed fun. He decided to provide after-match entertainment on the night of the Otago-Southland Ranfurly Shield match. There was one catch – finding the $4000 in 2016 dollars to hire the Dunedin Town Hall and pay a band. So the story goes, he drew on rabbit-catching skills learned as a boy. He borrowed £1 from his brother, used one half to pay his train fare, and the other half to buy the rabbiting equipment. Over a few days he gathered enough rabbit skins to stage the dance.

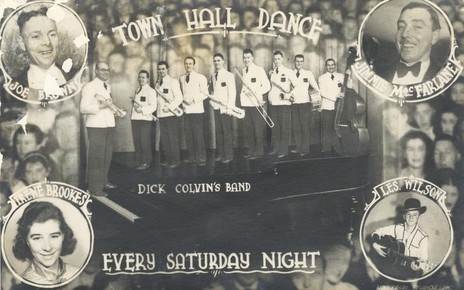

On Saturday, 1 August 1936, crowds flocked to the Ranfurly Shield Night Dance at the Dunedin Town Hall’s concert chamber. The supper room, with sit-down sandwich, ‘cuppa’ and sultana cake was especially popular. Brown doubled his money. By year’s end, his Saturday night dance was so popular that it shifted to the main town hall. For a quarter-century the dance was a Dunedin institution.

As always, Brown’s timing was good: night time entertainment was almost non-existent in a New Zealand that effectively went to sleep when hotels shut their doors at six o’clock. Apart from the cinema, there were few opportunities for young men and women to spruce up, go out on the town, and meet new people.

So many punters met their future spouse at the dance, including Brown himself, that it was jokingly referred to by some as “Joe Brown’s Matrimonial Bureau”. This moniker was only partly in jest: he met his wife Margaret at one of his town hall dances. Always the entrepreneur, he opened a Sunday afternoon tea room, so that couples who had met the night before could chastely nurture their friendship. He opened the Caledonian Catering Club for weddings, developed houses in Mosgiel for young couples, and opened a furniture business to fit out their first homes. He soon became wealthy, funnelling profits into other commercial operations including, eventually, his record label: Joe Brown (the sub-title was “… Presents the Tops in New Zealand Talent).

The dances proved so successful that when commercial radio station 4ZB began operating in 1937, Brown arranged for live national broadcasts. Thousands tuned in every Saturday night to the familiar trumpet blast of theme song ‘All Ashore’. During the war years as thousands of US marines were stationed here, American swing bands popped by, showcasing new styles of dancing such as the “bunny hop”. Young New Zealanders began to ‘go American’.

He would tell the bands to speed up the tempos, as this sold more orange cordial during the dances.

Brown enjoyed running gimmicks at the dances, such as treasure hunts, quizzes, dance demonstrations and talent quests. The evenings were more about entertainment than music. He would tell the bands to speed up the tempos, as this sold more orange cordial during the dances. A hard-nosed businessman, he cut corners to save costs, keeping strict control of the musicians’ fees at the town hall dances. Harry Strang, leader of the Excelsior Dance Band, which played modern dance in the main hall, recalled ‘bad feeling’, especially after public criticism over broadcast sound quality.

“We finally cornered Joe and told him we weren’t happy …. (that) if he didn’t come across the three bands would pull out …. And we finally got an extra half crown a player for the ones that played over the air….”

Eventually Strang started dances at St Kilda, in opposition to Brown, but he did admire his former employer’s skill at organising dances, and the musicians always got paid, if not quite what they wanted. In 2006, pianist Calder Prescott recalled him saying, “See those two trumpets there? They’re not even playing! I’m paying them the same money as the pianist!” As a businessman and promoter, “he knew exactly what was happening: he didn’t have the wool pulled over his eyes. He didn’t mistreat his musicians.”

By the mid 1950s, vigorous young jitterbuggers began to edge aside the old timers with their foxtrots, waltzes and sit down suppers. Sensing the change and the business opportunity, Brown controversially welcomed the rock’n’rollers. But the world was changing: the town hall dances were soon to close their doors.

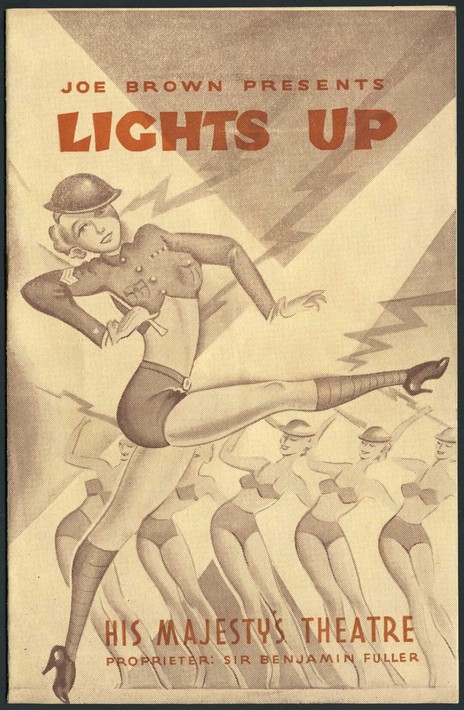

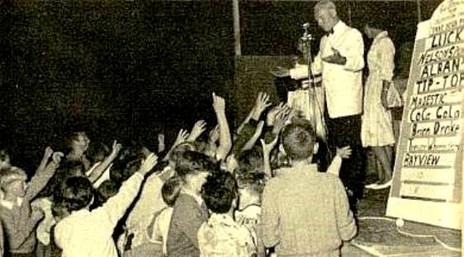

Brown had other things on his mind: acquiring the franchise for the Miss New Zealand beauty contest and running a national talent show, Search for Stars. The first Search took place in 1959, and the number of entries was phenomenal, with crowds waiting for hours to get into the regional finals. In Dunedin, more people attended the talent quest than went to a show in the same week by the Platters and Tommy Sands. The talent quest quickly expanded, so he hired well-known theatre managers George Tollerton and Trevor King to help with the organisation. From 1960 it became Radio Search for the Stars and was broadcast nationwide, hosted by Selwyn Toogood.

With the Miss New Zealand contest, Brown found a winning formula and cash cow that might be summed up as “beauty and the beat”. The young women entrants who flocked to the pageant supplied the beauty; the beat came from the old and new talent featured on the show. The Miss New Zealand contests were a great showcase for the acts on his record label.

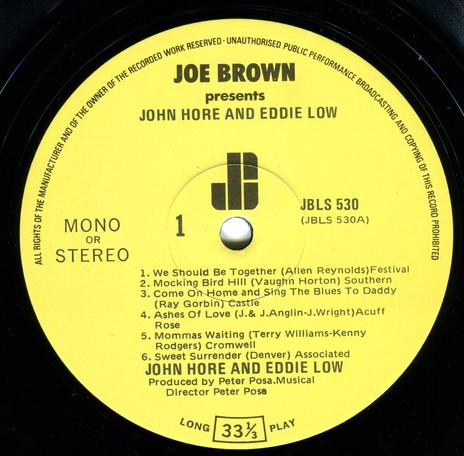

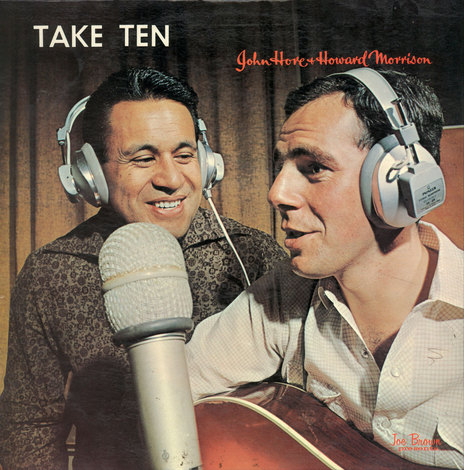

Stars signed to his label, Joe Brown Records, were meanwhile prolifically released and promoted, especially country acts such as John Hore (Grenell) and Eddie Low. The biggest seller came in 1976 with Return of a Legend, a recording of the Howard Morrison Quartet reunion shows the previous year.

The Miss New Zealand contest became a major national event through the 1960s and 1970s, attracting thousands of entries and filling town halls. After a series of heats, Brown shipped the swim-suited contestants around the country for three months of exhaustive touring, paying Miss Taranaki, Miss Auckland and the other regional finalists a weekly fee, before the big, closely watched showdown.

That was just the beginning. Once televised in 1970, the show drew an audience of a million, rising to two million by the early 1980s. By that time, womens’ groups routinely picketed the show, Brown responding: “I have been criticised for exploiting women but I believe I have been liberating them for years.” More New Zealanders watched the 1981 contest than the royal wedding of Prince Charles and Diana Spencer.

By the 1980s, Brown was increasingly based in Mosgiel, where he owned and trained many racehorses (one of which, Reformed, won the Wellington Cup and came third in the Melbourne Cup). A confirmed regionalist – ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ he always referred to as ‘Alexandra’s Ragtime Band’ – Brown believed local talent was as good as anything that came from overseas. He often lobbied the director-general of Broadcasting to feature more New Zealand artists on television and radio.

Brown died in 1986, an old school promoter who ushered New Zealand entertainment into the modern era.