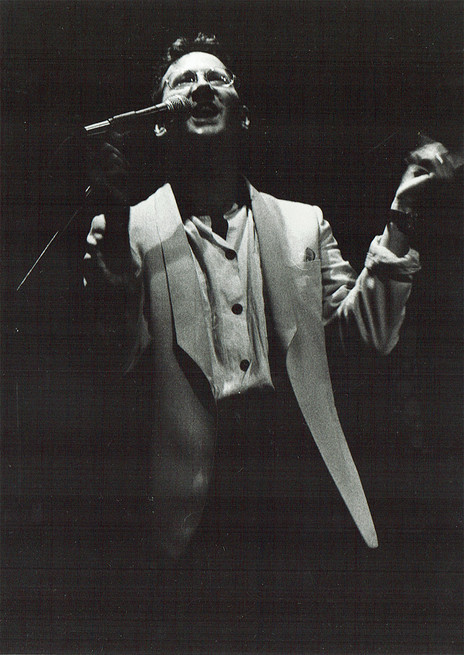

His own voice is a powerful and supple tenor which can rise to a plangent falsetto and has been known to inspire shouts of approval from congregations in African-American Baptist churches. But even more than the joy of soloing, it is the beauty that can be achieved when voices join together that has inspired and motivated him. Over the years he has turned bands of shaggy musos into soulful harmony groups, and halls of suburban singers into transcendent choirs.

Tony Backhouse was born in Auckland 1947 and lived in Titirangi until he was 11, when his family moved to Tawa. As a pre-teen he would tune his father’s transistor to the Lever Hit Parade and Cotton Eyed Joe’s Big Beat Ball, the only places on the dial “where they played anything that wasn’t Perry Como or Doris Day”. Hearing Elvis singing ‘One Night’ left a powerful impression. “There was all this furore about Elvis so I didn’t know what I was expecting, but it was completely unlike whatever I thought it was. It didn’t sound weird or raucous but it sounded really good.”

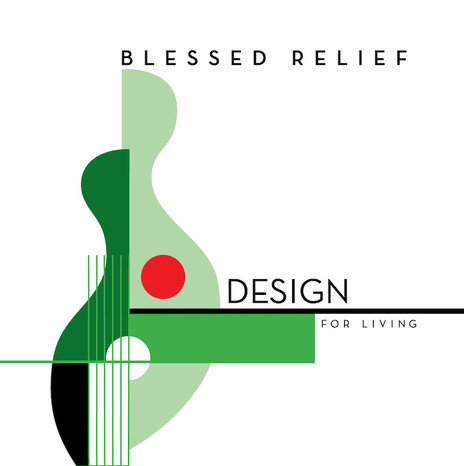

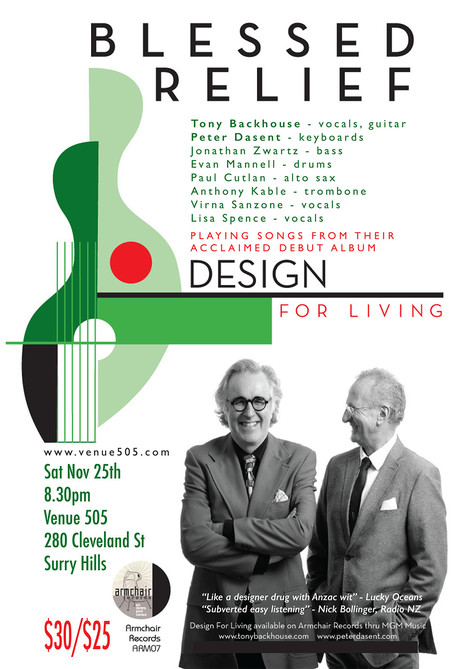

His early affection for Elvis would resurface some 60 years later in ‘Call Me Elvis’, a song he wrote with Peter Dasent, which the pair released in 2017 on the Blessed Relief album Design for Living.

Elvis was soon supplanted by The Beatles, and like millions of other teenagers around the world Tony asked his parents for a guitar. His father bought him “a dodgy old acoustic” on the proviso that he took classical guitar lessons, which to his parents made the instrument a little more formal and acceptable. It gave them the reassurance, he says, “that I wouldn’t just be bashing chords like a beatnik”.

His teacher was Wellington jazz guitarist Len Doran, who taught him jazz voicings and music theory as part of his guitar tuition. The theory came in handy in the madrigal group he joined at school, and would stand him in good stead when he went on to study music at Victoria University in the mid-1960s. “My theory was better than anybody else’s because they had all studied classical piano and it was all kind of linear, while I thought vertically as well as horizontally. So I really thanked Len for that.”

“I’m not fond of those creepy semitones, Mr Backhouse!” the composer warned him.

Tony studied composition with Douglas Lilburn and David Farquhar. He found Lilburn “quiet, quite shy” while Farquhar was more outspoken. “I’m not fond of those creepy semitones, Mr Backhouse!” the composer warned him.

In his final year of his degree Jenny McLeod returned from Europe to become, at 28, the youngest music professor in the Commonwealth. McLeod was more encouraging of his efforts, and for a while Tony became a resident of the house she bought in Brooklyn, which in the early 1970s was infamous for its parties and transient community of countercultural characters. One night the psychiatrist R D Laing came for dinner. Not long after, it was overrun by followers of Mahara Ji, the 15-year-old guru.

Alongside his education in western art music, Tony was making his first forays into writing and playing rock music. An early Backhouse original, ‘You Don’t Understand’, featured on Medallion, the second studio album of well-groomed Wellington pop group The Avengers. Meanwhile, Tony had joined – as bass player – the entirely un-groomed Original Sin, which included fellow students Bill Lake, Simon Morris and Rick Bryant. After two months he was fired by Morris, who didn’t think Tony’s playing was good enough.

Despite this rebuff, Tony remained friends with the members of the group and continued to develop his bass skills in the annual student productions. The 1969 “Extrav” featured John Clarke (later to find fame as Fred Dagg) and Michael McDonald (who with his sister Ginette would go on to mastermind the Lynn of Tawa persona) along with small cameos by Bryant and Morris. The following year the production was taken over by incoming Student Arts councillor and alternative entrepreneur Graeme Nesbitt, who relaunched it as Embryo, a psychedelic happening. “We’d have rehearsals where we’d toss the I-Ching to see what we’d do next,” Tony remembers. “It was all sort of ‘living theatre’. At one point we even swapped the beginning and the middle around and it seemed to make just as much sense. It was about a week-long run, but let’s say it was not met with universal acclaim.”

He also played bass in the rock musical Jenifer, composed by Clive Cockburn of the Avengers, and Santa’s Liquid Dream, another university “happening” conceived by fellow composition graduate Ian McDonald, plus a brief stint in an unnamed band with Lindsay Field (who would go on to a long career with John Farnham) and Original Sin drummer Jeff Kennedy.

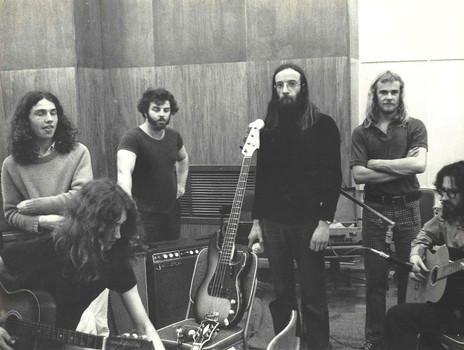

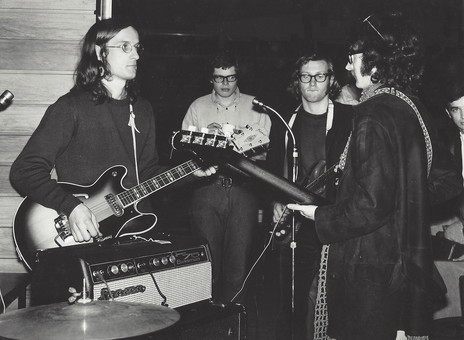

By this stage Simon Morris had evidently changed his mind about Tony’s bass playing as he asked him to join Bill Lake drummer Mark Hansen and himself in a new group, The Mammals – or Simon and the Mammals as they were sometimes called, due to Simon being the most visible member.

The Mammals (a name that was quickly abbreviated to Mammal) worked up an ambitious repertoire that included songs by Jack Bruce, Frank Zappa, The Moody Blues, Spooky Tooth and The Band, along with some fledgling originals, and began to gain some recognition with gigs around the campus. But when they opened for the debut performance of Highway at the Paramount Theatre during the 1970 Student Arts Festival they found themselves outclassed. “Highway had been rehearsing for months and were tight and amazing. We got very stoned beforehand and when Mark Hansen counted in Neil Young’s ‘Helpless’ in 3/4 instead of 4/4 it was more or less the end of the group.”

While Hansen and Morris went on to form Tamburlaine, Lake and Backhouse retained the Mammal brand and were joined by Rick Bryant and guitarist Robert Taylor, who had been playing together in Rick and the Rockets, and the Gutbucket rhythm section of Steve Hemmens and Mike Fullerton. With Hemmens now filling the bass role, Tony moved to piano, while taking advantage of the expanded lineup to arrange ever more elaborate vocal harmonies.

The new lineup of Mammal made its debut in 1971. Bryant’s big bluesy voice and abiding love of black American music saw the repertoire grow to include a number of classic Motown songs: the Temptations’ ‘Cloud Nine’ and ‘Can’t Get Next To You’, Gladys Knight’s ‘I Heard It Through The Grapevine’ and Marvin Gaye’s ‘Ain’t That Peculiar’, which were showcases for Tony’s vocal arranging. In ‘Cloud Nine’, Rick gave a convincing interpretation of Dennis Edwards’ gruff lead while Tony delivered a perfect facsimile of Eddie Kendricks’ soaring falsetto, with Bill and Robert adding to the choruses.

‘Play Nasty For Me’ became a 25-minute epic, bewildering audiences wherever it was performed.

The rest of the set was eclectic, particularly the originals which they were constantly rearranging. One tune, ‘Masquerade’, carried over from the original Mammals, evolved to include extended instrumentals in 7/4 time. Another, ‘Play Nasty For Me’, which started as a country parody by Tony, became a 25-minute epic; a mini-history of rock’n’roll incorporating heavy metal, surf music, German music hall and psychedelia, bewildering audiences wherever it was performed.

By this time, Tony had finished university and taken a job as a presentation officer at the NZBC where he worked alongside fellow musician Midge Marsden, programming music for the numerous stations administered by the public broadcaster.

“You had listening booths, these little Tardis’s, and you’d have carte blanche to go in there and audit a few albums, maybe smoke a bit of pot before you’d go in. You could kill a lot of time there.”

He would also find obscure songs to boost the Mammal repertoire, by groups like Rasputin’s Stash and Ten Wheel Drive. Tony’s job required him to move frequently between the music library and the main office, so if his colleagues couldn’t find him at one location they would assume he was at the other. In actual fact he was usually in one of Broadcasting House’s basement studios, writing songs and practising the piano.

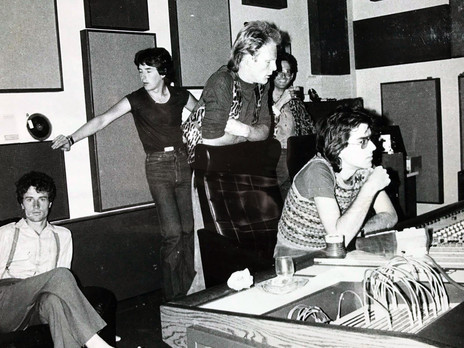

Broadcasting House also provided the facilities for Mammal to make demos of their songs, and it was where they went to record their only album, the 1972 release Beware The Man, a collaboration with poet Sam Hunt. The brainchild of publisher Alister Taylor and composer Ian McDonald, it presented Hunt’s words in a variety of setttings, sometimes as full-blown rock songs, other times as readings with instrumental accompaniment. It included an interlude by the Alex Lindsay String Quartet and a synthesiser soundscape recorded by McDonald in the Victoria University Electronic Music Studio. McDonald wrote half the tunes, the rest were by Tony. Though the album didn’t truly represent the way Mammal sounded on stage, the title track, written by Tony, became a staple of their repertoire and a recognised crowd-pleaser.

Slightly more typical was a single, ‘Wait’/‘Whisper’, recorded the following year. ‘Whisper’, another of Tony’s songs, featured a baroque four-part vocal arrangement over a bluesy rock groove.

When Mammal set out with Hunt on a nationwide tour, Tony threw in his radio job. “I didn’t have any plan. I just wanted to play in a band. That was the beginning and the end of my thought. There was no ‘we’re going to make a record, we’re going to do this, we’re going to do that’. I wanted to write songs. And in the back of my mind was ‘and we’re going to be as big as The Beatles’, but I had no way to do it.”

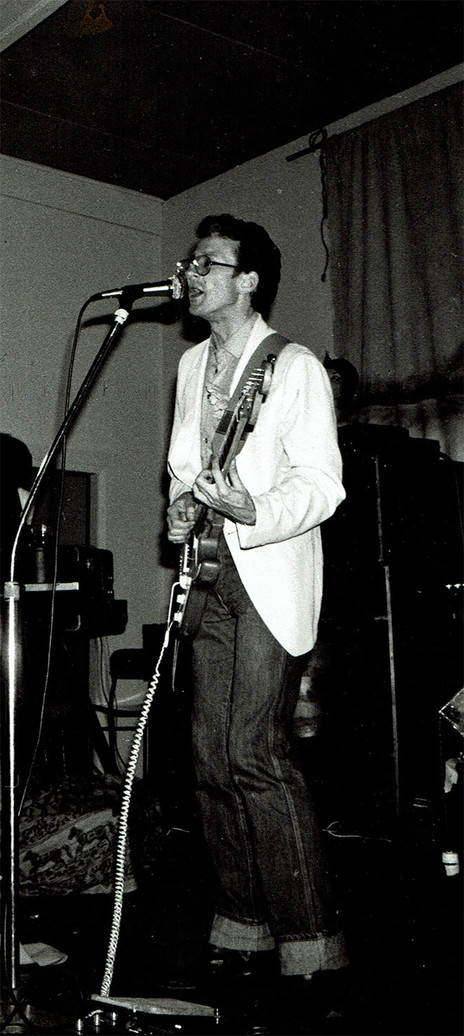

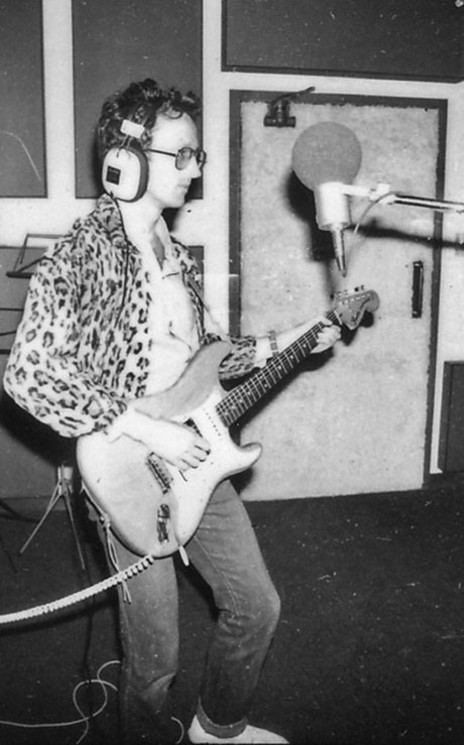

When Bill Lake left Mammal in 1973, Tony shifted to guitar from the piano, which had often been inaudible due to the limitations of the group’s sound system. Mammal toured extensively through 1973 and 1974, often double-billing with other groups who were striving to make headway with original and non-mainstream music, such as Split Enz, Dragon, Billy TK & The Powerhouse and Tamburlaine.

Mammal’s tours took them to the regional backblocks, where they were often met with a perplexed response.

Too experimental for the pub circuit, their biggest audiences were at universities, one-off concerts in town halls and opera houses, and the occasional festival. But their tours also took them to the regional backblocks, where they were often met with a perplexed response. “We had no idea. ‘Play Nasty For Me’, 26 minutes of mayhem. It didn’t occur to us that because there were only six people at the Archery Club in Hastings that there might be something wrong with our repertoire or our presentation or any of that sort of stuff.”

Mammal played their final show in late 1974, with Bryant moving on to BLERTA and Taylor joining Dragon. In need of income, Tony joined Dave Feehan’s well-established Wellington band Tapestry and stepped into regular club work, playing several sets a night, several nights a week. In stark contrast to Mammal, Tapestry combined high-level musicianship with crowd-pleasing professionalism. Their repertoire of 70-odd songs included recent Bee Gees and Average White Band hits alongside musicians’ favourites by the likes of Steely Dan and Tower Of Power. As the group’s only guitarist, as well as contributing to the vocals, Tony “had to really step up. It had the effect of tightening up my playing, but I also had to think about the nuts and bolts of how those songs were devised.”

When Feehan disbanded Tapestry in 1976, Tony formed a new band, Hired Help, with two old friends, Bill Lake (from Mammal) and Clive Cockburn (of the Avengers), with a view to working the Wellington pub circuit. They fashioned a danceable repertoire that mixed a smattering of original songs with funk from the likes of the Meters and Little Feat.

It was around this time that Tony began receiving calls from former BLERTA guitarist and songwriter Fane Flaws. In the last days of Mammal, he had guested on some Flaws demos. Now the irrepressible Flaws had plans to start his own group.

“We had recorded a whole lot of his songs which were really good so I knew what he was about. Anyway, he told me ‘I’ve found a new great piano player’ who turned out to be Peter Dasent, and ‘I’ve got Bruno Lawrence on drums’.

“I was happy in the band with Bill and Clive. It was rocking along, we were doing some of my own songs. But Fane rang up every morning and gave me the same fucking rave. ‘It’s kismet mate! We’re both Geminis! You deserve to be in this band…’ and finally I gave in.”

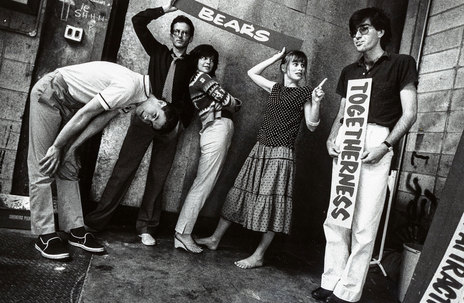

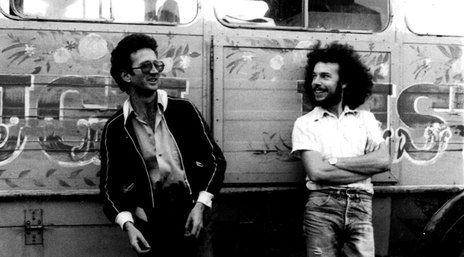

By the end of 1977 Hired Help was over and Tony had moved to Paekakariki where he was rehearsing and sharing a house with the members of what would become Spats. They hit the road in 1978 in the former BLERTA bus, interspersing originals with covers of Frank Zappa and Django Reinhardt with little regard for what a regional pub audience might want to hear. Outside the major centres they were often met with the same kind of indifference that had greeted Mammal five years earlier.

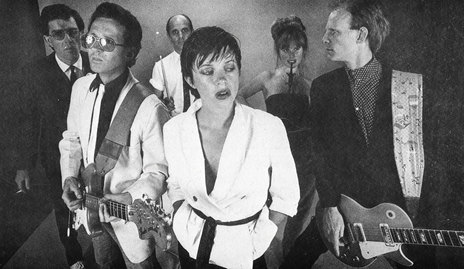

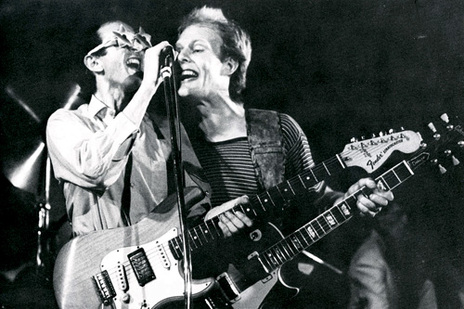

Undaunted, Flaws came up with another plan: Spats would reinvent itself as a new wave pop group, The Crocodiles. In the meantime, with Spats defunct and the Crocodiles still in incubation, Tony joined Rick Bryant’s Rough Justice on guitar and vocals.

“That was where my heart was at. Soul music. The Crocodiles was going to be a little side thing, a pop thing to make a bit of money. I wasn’t really interested in the sort of Brit-pop that Fane and Peter were writing, even though I listen to it now and it’s great. Great songs. But at the time it seemed to be celebrating the ephemeral, so I didn’t contribute that much initially. But when we started recording I started writing more.”

The Crocodiles’ path to the studio was guided by visiting American record producer Kim Fowley, whose previous proteges had included all-girl band The Runaways and one-hit-wonders the Hollywood Argyles (‘Alley Oop’) and, more recently, Auckland’s Street Talk.

Kim Fowley kept telling the Crocodiles “to be more moronic.”

“I remember being in the studio for three days, playing our songs with Kim raving at us non-stop. We’d get through about four bars and he’d go ‘Next!’ Brutal. But very entertaining. He kept telling us to ‘be more moronic.’”

Fowley soon returned to Los Angeles, leaving the Crocodiles in the hands of local producer and engineer Glyn Tucker Jr. who saw their debut album Tears through to completion. On its release in 1980 the title song became a local pop hit, and Tony found himself playing lunchtime concerts in secondary schools “flinging chocolate bars to school kids. It was a bit weird but I guess we got paid a lot, which I think was the point.”

Before the Crocodiles recorded their second album Looking At Ourselves, Fane left to pursue yet another project. By the time the group left for Australia in 1981, Tony and singer Jenny Morris were the only original members left. Sydney was supposed to be a pit stop on the way to Europe (“Kim Fowley said we’d be big in Germany or Holland”), but it wound up being the band’s final resting place. Australians, it seemed, had little time for clever Kiwi pop. “We just weren’t going to make it. It was the wrong culture.”

A positive outcome of the Crocodiles experience was that Tony began writing songs with Arthur Baysting, who had co-written ‘Tears’ with Flaws. “Arthur would insist that we write a complete song in a single sitting, and then start another one. I’d never done that before. I discovered that it didn’t have to take me 12 months to write six bars.”

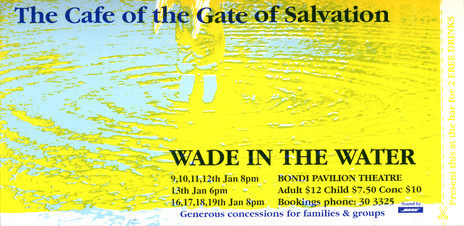

A couple of the resulting collaborations – ‘God Made the Rhythm Machine’ and ‘All Of Heaven’ – would later feature in the repertoire of his choir Café of the Gate of Salvation.

Remaining in Sydney, Tony formed a new group, The Vulgar Beatmen, with fellow expatriate New Zealanders Mike Gubb (keyboards), John McKay (drums), Peter Boyd and Peter Famularo (saxophones), Jonathan Zwartz (bass), and Jane Lindsay (vocals). This time the focus was on soul/R&B, with a high proportion of Backhouse originals. Though the band was tight and the repertoire reflected Tony’s tastes, it only lasted a couple of years. Around this time Tony played briefly with Australian soul star Renee Geyer, who cut a soulful and snappy single of Tony’s song ‘Love So Sweet’, but for much of the 80s he supported himself by working in a café.

It was during the café years that he had something of a musical epiphany. It began with seeing visiting Canadian vocal quartet The Nylons, who sang their entire set unaccompanied.

“Hearing the Nylons made me realise this was what I’d been trying to do all along. In Mammal I had worked out all the Temptations harmonies and taught them to the band because that was what I liked to do.

“Instead of getting the drummer to sing a harmony, let’s get rid of the drums and just let him sing. A lot of things were possible for voice that I hadn’t considered before. And if I got a group together that didn’t have to carry anything that would be really good.”

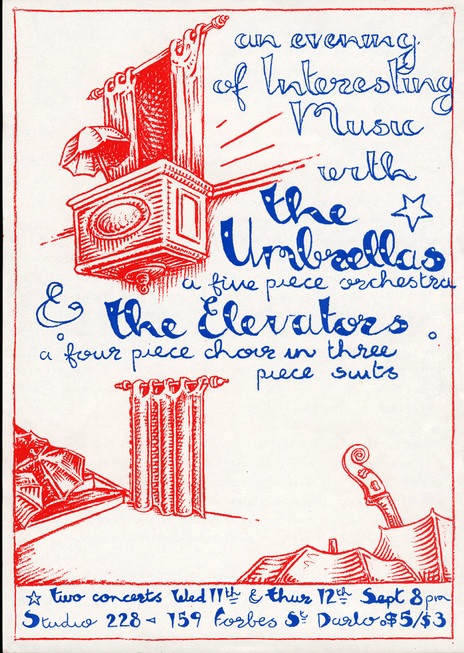

Tony formed The Elevators, a vocal quartet which included fellow New Zealanders Simon Emsley and Patrick Leniston (plus Australian bass Frank Zeichner.) Unburdened by the traditional hardware of rock groups, the Elevators were a compact and portable unit and could perform anywhere from the corner of a café to an opera house stage.

During this time Tony was listening to an increasing amount of African-American gospel, especially the vocal quartets whose style and material helped shape the Elevators’ sound. It was clearer than ever that this was the source of the soul and R&B vocal music he loved. A one-off collaboration with all-women quartet Wild Wild Women (an a cappella arrangement of Clara Ward’s ‘How I Got Over’) got him thinking about the possibilities of a larger ensemble, so one day in 1986 he put up a notice in the café: Singers wanted to form gospel choir. Buddhists welcome.

in 1986 he put up a notice in the café: “Singers wanted to form gospel choir. Buddhists welcome.”

A jumble of Jews, agnostics, atheists, spiritualists, and, yes, a couple of Buddhists – about 40 in total – turned up to an initial meeting in Tony’s flat and the Café Of The Gate Of Salvation was born, borrowing its name from an ancient Turkish cafe Tony had read about. ‘How I Got Over’ was the first song they sang. The repertoire quickly grew to encompass both classic and more recent gospel songs, along with originals by Tony and, later, other members of the choir.

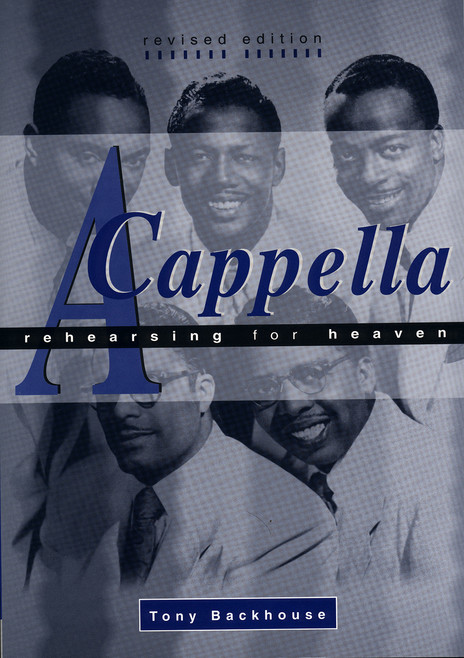

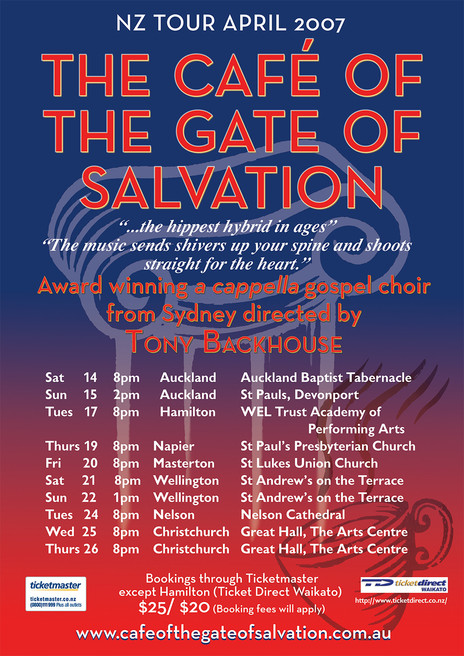

Over the next few years, the COTGOS travelled to concerts and festivals around Australia, building a reputation for stirring, uplifting performances. Their music was featured in Jane Campion’s 1989 film Sweetie. Around the same time he co-founded the Sydney Acappella Association to promote unaccompanied singing traditions.

In 1988 Tony made the first of many trips to the United States to experience live gospel music in its birthplace. He visited black churches in Memphis, Alabama, New Orleans, Chicago, New York and elsewhere, where he attended rehearsals and services. He met and became friends with a number of the music’s working practitioners as well as some of its retired heroes. He also attended workshops by Joseph Shabalala, founder of the South African vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Drawing on his experiences, he began to hold his own vocal workshops around Australia and New Zealand, out of which further groups emerged such as New Zealand’s Heaven Bent and Jubilation choirs, and in Canada, Britain, Italy and France. He took groups from Australia on gospel tours of the United States, to witness the powerful music in situ, and singing tours to Samoa, Fiji, Bali, and remote parts of Australia, interacting and collaborating with local communities. His repertoire expanded to include some of the songs learned on these field trips, along with material from the likes of Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

During a six-month stint at the University of Memphis, Tennessee, he completed a paper in ethnomusicology, writing on the evolution of a cappella gospel quartets from the 1920s to 1950s, notating the music from recordings and “trying to figure out how it all worked.” This range of work, almost all of it centred on gospel and a cappella music, would occupy him for most of the nineties and into the 21st century.

BACKHOUSE

“WENT SIDEWAYS

INTO THE

A CAPPELLA WORLD AND DIDN’T PLAY GUITAR FOR ABOUT 20 YEARS.”

In the mid-90s he formed another a cappella group, the Heavenly Light Quartet, with William Selwyn, Stuart Davis and Rob Maxwell-Jones (the Elevators having broken up after a couple of years in the late 80s.) As well as recording an album, the Heavenly Lights performed backing vocals for Tim Finn, Renee Geyer and Margaret Urlich.

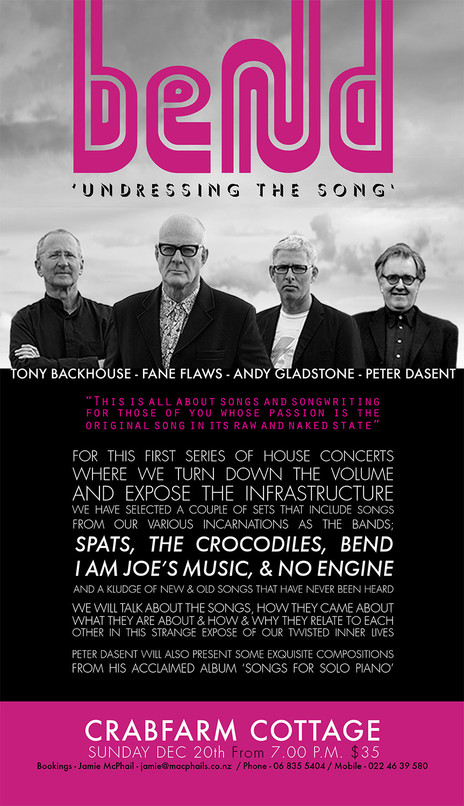

Though, as he says, Tony “went sideways into the a cappella world and didn’t play guitar for about 20 years”, he has nevertheless maintained friendships and musical relationships with the likes of Fane Flaws and Peter Dasent. In the late 2010s, while living for a period back in New Zealand, he resumed playing with Flaws in the Napier-based No Engine and with both Flaws and Dasent as The Bend.

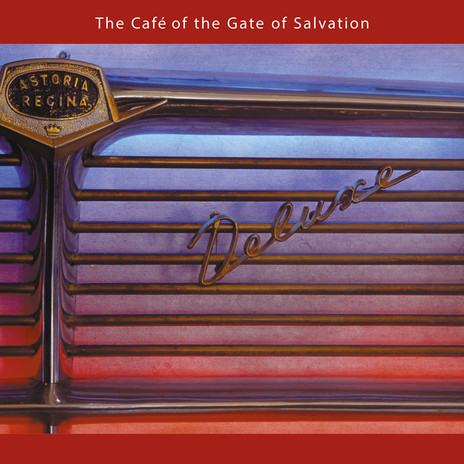

In 2017 he and Dasent, as Blessed Relief, completed and released a project begun 30 years earlier: Design for Living, an album of songs written by the pair and recorded with an ensemble that includes Jonathan Zwartz, Frank Dasent and, for one track, the late Bruno Lawrence. The music is sophisticated and detailed, with traces of funk, bossa nova and Italian film music. The lyrics, mostly by Tony, are whimsical and nostalgic. The singing is spectacular.

--

Read more: Tony Backhouse’s a cappella epiphany