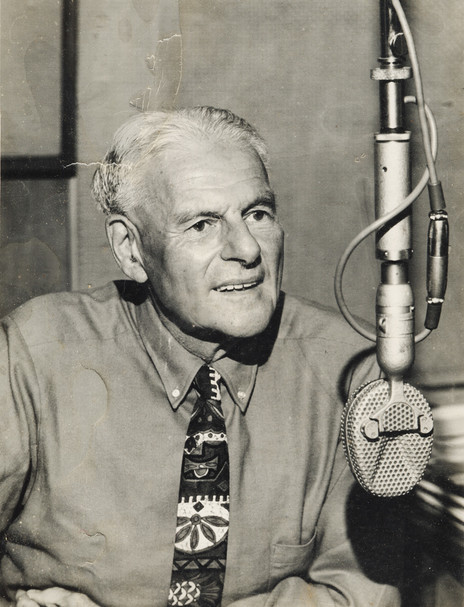

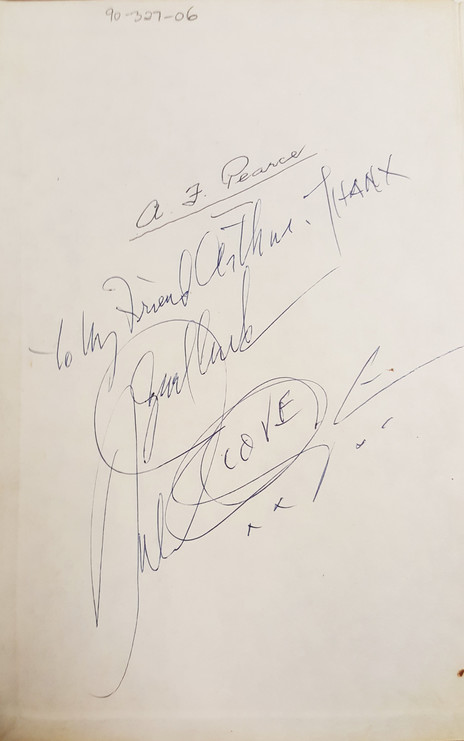

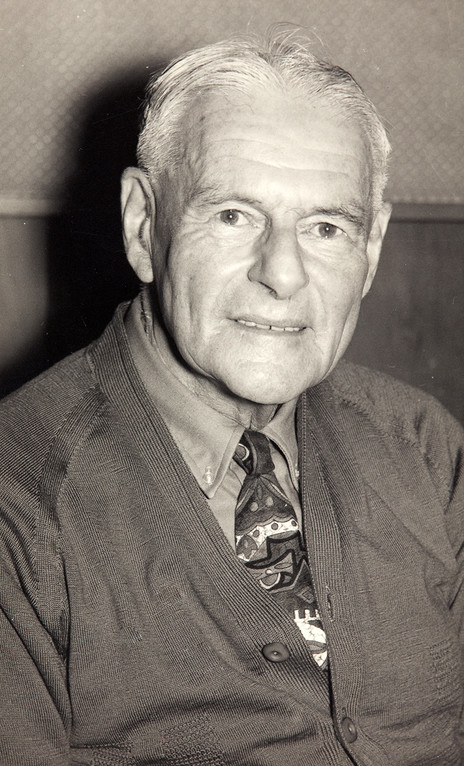

Stringing a conceptual thread through these non-matching pearls was a man with a light, ageless voice, who identified himself as Cotton-Eyed Joe and spoke in a bewildering stream of puns. He was veteran Wellington broadcaster Arthur Pearce.

Pearce was into jazz before most people knew the word.

His 40-year career in broadcasting paralleled both the growth of New Zealand radio and the development of 20th-century popular music.

Born in 1903, Pearce was into jazz before most people knew the word. At a dance class in his early twenties he had chanced upon a recording by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Contrary to their name, they were not the originators of jazz. Still, this white New Orleans group was the first to get a version of this hot new sound onto disc. Compelled by this exotic music, Pearce – working by day for trading company Levin and Co., of which he would eventually become a manager – persuaded officers on American-bound ships to track down the recordings for him.

His tastes quickly moved towards the black musicians of the American South, the music’s true originators – Ma Rainey, Ida Cox, Johnny Dodds, Louis Armstrong. These so-called “race records” were generally advertised and distributed only by mail through the black media. Tracking down and getting the shellac 78s to New Zealand was a feat in itself.

Today when Radio New Zealand gives airtime to hip-hop there are grumbles from rap-resistant listeners, but these hardly compare with the outcry that followed Pearce’s first radio broadcast, which was devoted to the music of black bandleader Duke Ellington. In 1935, the first exposure of radical American music on New Zealand airwaves saw the public broadcasting station 2YA and newspapers showered with complaints. Of course, it also initiated a generation of jazz listeners.

In 1937 Pearce was invited to debate the popular new crooning style on air with Stanley Oliver, head of Wellington’s Harmonic Society. As Chris Bourke notes in Blue Smoke: “Oliver – in good humour but also with relish – described crooning as ‘a menace to the real art of singing’ … Pearce responded with a well-researched explanation of the developments in popular music and technology that had enabled crooning to flourish.”

That same year, as the swing craze boomed, Pearce – using the pseudonym Turntable – began to host 2YA’s Friday night dance band slot, Rhythm on Record. From early 1938 he added a theme tune, ‘Woman on my weary mind’, recorded by Bob Crosby, and for 25 years he opened each show saying, “Hello, this is Turntable calling. Any rags, any jazz, any boppers today?”

Among the more sanitised (read, white) swing records, he would slip in recordings of his favourite black performers. Later, these would include examples of the burgeoning rhythm and blues, by favourites such as Louis Jordan and Johnny Otis.

Pearce would sometimes present recordings of local jazz concerts, to which he applied his discerning ears. Recalled pianist Ken Avery: “To close one particular concert we decided to have a giant jam session with about 15 players on stage each taking solos in turn. When the time came to present this on air, Arthur Pearce was able to identify every soloist.”

It was during World War II that a teenage Laurie Lewis (who would later write Pearce’s biography, Arthur and the Nights at the Turntable) first began tuning in to Turntable. “I was always twiddling the dials, usually late at night, to my parents’ disapproval. You don’t sit up and mess up tomorrow’s schooling listening to jazz programmes! I got mad on the saxophone. In those days, there was nobody at all to teach you, except in the classical field. But here was this wonderful man, explaining who all these musicians were and where they came from. He exposed you to things that were happening in America that you had absolutely no other way of hearing.”

Another listener upon whom Pearce had a formative influence was Ray Harris, who would go on to become the Listener’s long-serving jazz columnist and host his own jazz programmes on radio and television. For a while his NZBC radio show alternated with Pearce’s, though by Harris’s admission his were the more mainstream, Pearce having much wider tastes and greater to access to older and obscure material.

Cotton-Eyed Joe would intersperse tracks with off-the-wall humour.

Pearce also developed a taste for western and hillbilly records that were coming out of the southern states and, in 1948, launched Western Song Parade. This was where the Cotton-Eyed Joe persona first raised its head. Borrowing his name from a record by western swing bandleader Bob Wills, Cotton-Eyed Joe would intersperse tracks with a mix of discographical information and off-the-wall humour.

“Ozark Red, who leads the Ozark Mountain Boys, is really Rusty Draper, for here is a draper who curtains his real identity to escape from many a hanging …”

“The puns were absolutely extraordinary,” Lewis recalled. “We used to compare reaction to the programmes at school and everybody would hear it a different way. They were so personal that you had to know a bit about the artists involved to understand half the jokes.”

Later, when he got to know Pearce, Lewis discovered that the puns were tossed off effortlessly. “Those scripts were just little spidery, handwritten bits of paper all over the place.”

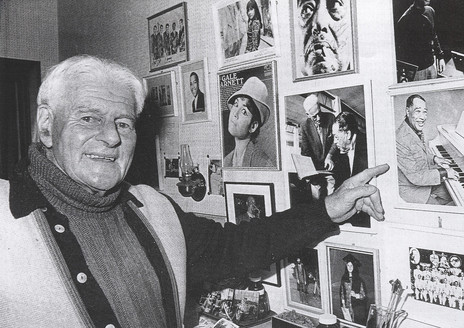

Pearce’s knowledge of American music – the players, the writers, the producers – grew to encyclopaedic proportions. In those days little existed in the way of music media, so he would write directly to artists to find out whatever he could not glean from record labels or his own finely tuned ears. He corresponded with, and received detailed replies from, musicians as diverse as Duke Ellington and Carole King.

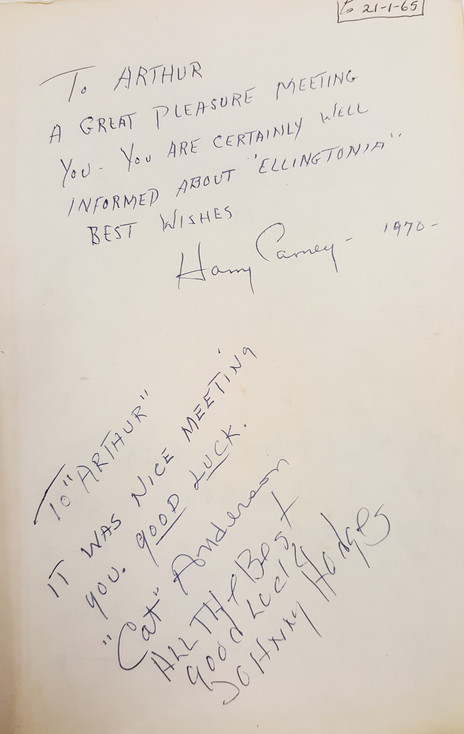

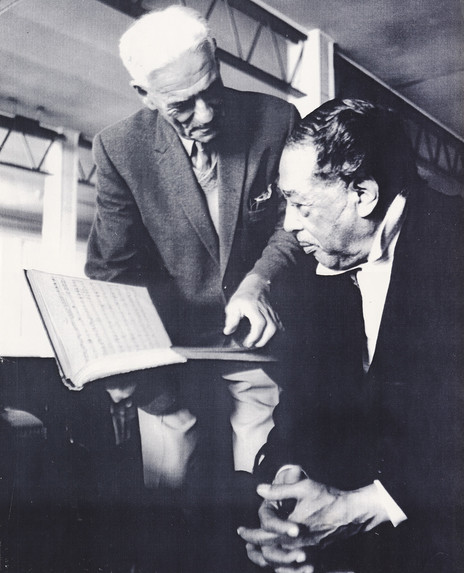

With Ellington, Pearce developed a special rapport. He offered the composer a set of lyrics he had written to Ellington’s tune ‘Black Butterfly’ and these subsequently appeared with Ellington’s published sheet music. When Ellington toured New Zealand with his orchestra in 1972, he performed the tune for the first time in years, dedicating it to “an old friend” who was in the audience that night. After Ellington’s death, the bandleader’s son, Mercer, told Pearce’s son, Neil, that the Duke said Arthur Pearce was one of the few people who really understood him.

As R&B became more prevalent on the Western Song Parade, the programme’s name changed to Big Beat Ball. When Elvis Presley came to rock the foundations of popular music in the mid-50s, Pearce was the rare listener who was not taken by surprise. For years, he had been telling people that, sooner or later, a white singer with a black feel would be the catalyst for a new direction in pop. When he debuted Presley’s Sun sides on the jazz-oriented Rhythm on Record, purists who failed to share his broader view of music howled in protest, just as an earlier generation had when he first played Ellington.

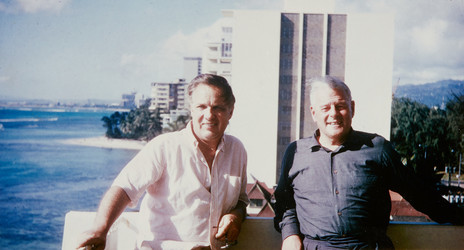

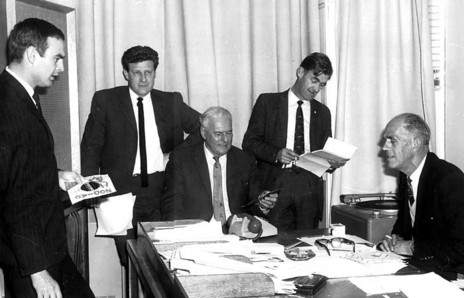

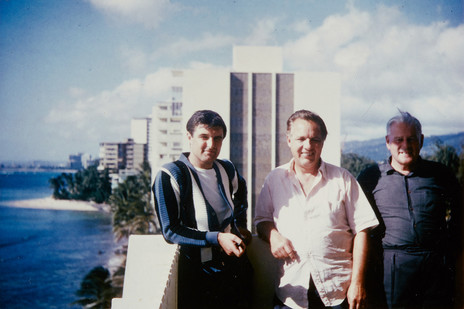

By the 60s, jazz and rock artists from the US and Britain were touring New Zealand regularly. Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Dave Brubeck, Gene Pitney, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles … Pearce met them all, yet these valuable interviews were never recorded. Lewis surmised that, because Pearce grew up before the advent of tape recorders, it never occurred to him to use one. “He never even took any notes. As far as he was concerned, these were just conversations to check up on as few things he thought he might be wrong about.”

Such was the case when, at a reception for the Dave Brubeck Quartet at Wellington’s Royal Oak Hotel, Pearce buttonholed saxophone player Paul Desmond. Ray Harris remembered: “They went into a corner of the lounge and they were there for a long time, and when they came back, Arthur left, and I remember Paul Desmond saying, ‘Who was that guy?’ ‘Oh that was Arthur Pearce, does a programme on the radio, Rhythm on Record.’ ‘Well, he knew more about my bloody life than I know about it myself!’”

When Pearce was asked how he got into the Beatles’ hotel, he replied: “Partly by car, partly by Kerridge.”

Neither is there any recording of the exchange that took place in the St. George Hotel when Pearce, then 60, visited the Beatles in 1964. But by Laurie Lewis’s account, the broadcaster reduced Ringo to hysterics with a typical Pearce pun. The tour had been promoted by the RJ Kerridge Organisation and when Pearce was asked how he got through fans and security into the hotel, he replied: “Partly by car, partly by Kerridge.”

Meanwhile, local teenagers were discovering a world beyond the Beatles, thanks to Pearce’s eclectic playlists. College student Rick Bryant, who would become one of New Zealand’s most celebrated interpreters of blues and soul, stopped mimicking the British beat groups and began emulating black vocalists like Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding after encountering them for the first time on Big Beat Ball.

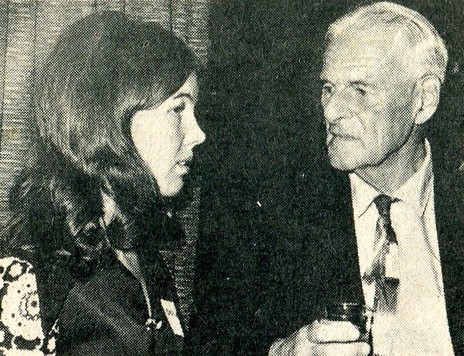

Susan Pointon was 15 when she heard the Chicago blues on Pearce’s show. Thrilled by this passionate and gritty music yet unable to find any in local stores, she wrote to Pearce. They arranged to meet on the Wellington waterfront, where he presented her with a stack of rare Chess singles: Howlin’ Wolf, Little Walter and others. But her parents took some convincing that the schoolgirl and the 60-year-old man were simply two music fans getting together to share their enthusiasms.

Lewis – a dyed-in-the-wool jazzer – stopped short of calling Pearce’s affection for rock and blues a lapse in taste, although it obviously puzzled him. “I’d go round to his place to hear my favourites, and would come away almost frustrated. He would always play the weirdest records. It was like getting a private programme.”

Among those hooked on Rhythm on Record was fledgling jazz pianist Mike Nock. “I used to listen to it as a kid,” he told RNZ in 2024. “He’d say, ‘Any jazz, any blues, any beboppers today?’ That was his call sign. He would play the latest music from the US, it wasn’t all jazz, but it was comprehensive. There were little groups all over New Zealand that would study this show and get together and talk about it.”

For many listeners, the magic of Pearce was in the sheer diversity of his palette. As a pre-teen, writer Gordon Campbell was a dedicated Big Beat Ball listener. He remembers trading in a telescope for a reel-to-reel tape recorder to record the programmes.

Later, in the mid-1960s, Campbell worked at the NZBC as a producer of Pearce’s shows. “I was in awe of him. The thing that floored me was his passion for these things that were completely subterranean – surf groups, American garage, which was then called ‘punk’. He was about 30 years ahead of so many fashions, with no kindred spirits to feed off. Tarantino has only just caught up with him.”

At a time when all New Zealand radio was government owned, Pearce was a law unto himself. Lewis: “Everything was so strictly controlled. Even records that were top of the charts in overseas countries … a committee would decide, in their wisdom, that they didn’t like them and that was it – nobody was allowed to hear them. For years, Bugs Bunny was banned from the airwaves in New Zealand! But Arthur was working in an area where nobody else knew enough even to argue with him.”

Big Beat Ball stayed with 2YD through its rebranding in the late 60s to pop-oriented 2ZM. But Radio New Zealand dropped the programme in 1975, saying it no longer fitted the format. As if it ever had. A typically eclectic final programme featured Captain Beefheart, Earth Wind & Fire and “Mr Las Vegas” Wayne Newton.

Two years later, Pearce farewelled radio with his last Rhythm on Record. Until he died in 1990, he continued to keep up with a vast range of music. Neil Pearce recalls his father enthusiastically introducing him to the first Ramones album in 1978; his father was then aged 75. “I had to say, ‘Dad, I think I’m too old for this.’ But he would recognise anything that was good of its type. By then, jazz was mostly seen as music for older people and rock for the young, but he liked it all. He could see how one thing developed out of the other. He was there when it happened, and he could always hear the connection.”

--

An expanded version of an article first published in the Listener, 17 January 1998