This was a revelation in more ways than one. Growing up in Horohoro, southwest of Rotorua, music had never been a feature of Adrian’s home life, to the extent that he would only dare sing along to his radio once his parents were fast asleep.

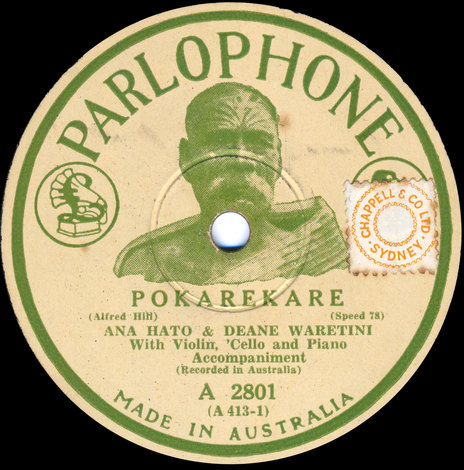

“I didn’t even know he could sing,” Waretini told the New Zealand Herald. “So when I heard about it – I was about 12 – I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t even see Dad’s record until I was 23, he’d been dead for two years. I just held it in my hands, staring at it. It was one of those really old, thick records [a 78rpm disc] ... I don’t think it was ever something he wanted us to get into. Dad always said education would be best for us: ‘You eat of that food,” he’d say, “it will set you up for a better life’.”

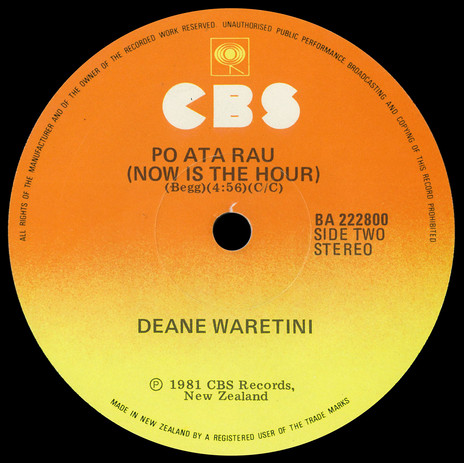

in 1981 Waretini became The first artist to top the charts with a song in te reo Māori.

With new-found pride in his family, Adrian eventually changed his name to Deane Waretini Jr and began taking his first steps toward creating a legacy of his own.

Because if his career has repeatedly misfired, Deane Jr can still lay claim to a huge achievement: the first New Zealand artist to top the charts with a song in te reo Māori.

In 1960, he had joined a local Rotorua group. He’d shown up for his audition wanting to play guitar – he had learnt a few chords to impress the girls – but the 14-year-old’s dream was foiled when it was pointed out that he didn’t own one.

Luckily he knew some songs from the radio and won a spot in the newly dubbed Tremeloes. After 18 months of rehearsals they booked their first gig, a Friday night spot at the 600-capacity venue Ritz. They turned up in second-hand suits, played to an all-but empty room and were pulled off.

Waretini: “I didn’t care, I was just happy to have played at all. The fullas didn’t get that, they were just pissed off because we’d been booted.”

He was living in Christchurch as a gigging/odd-jobbing, father of two when he learned of his father’s death. At the funeral he met his cousin and Te Arawa elder, George Tait.

“He became my manager,’’ said Waretini,“but he was much more than that. He knew how much my father loved me, but I was a cocky little bugger and people didn’t usually take any notice of me because I kept pushing myself forward.

“But George had faith in me and he wanted to keep my father’s name alive.”

It was Tait who suggested Adrian change his name to Deane Jnr. Not only would it end the constant questions around his relationship to the famous Māori singer, it might get him some gigs.

In 1970, Waretini travelled to Auckland where he finished second in a North Shore-based talent quest before appearing on the “Golden Opportunity” segment of popular television show, Happen Inn. He went on to enter the televised New Faces competition, making the finals, and then recorded his first two singles, ‘Troubles in My Life’ and ‘Melody Butterfly’ for the Tony McCarthy Recordings label.

Tait then used his war pension to get the 21-year-old to Australia, where he met former Howard Morrison Quartet singer, Wi Wharekura. Armed with plenty of sage advice, Waretini returned home to work up a showcase act and join promoter Joe Brown’s talent stable.

In 1973, he submitted ‘Baby I’m Leaving’ as a possible theme song for the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, only to lose out to Steve Allen’s ‘Join Together’.

The following year he returned to Sydney for a two-month stint which saw him performing at South Sydney Junior Leagues Club, the Mandarin Club and the Motor Inn.

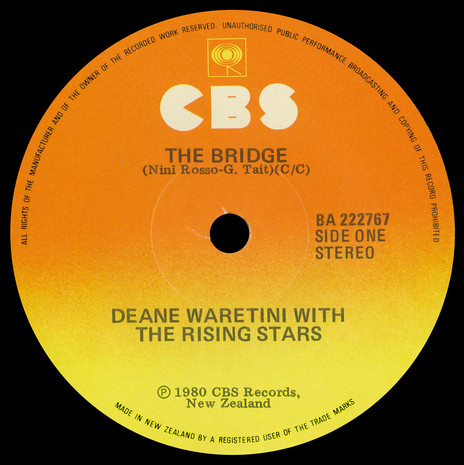

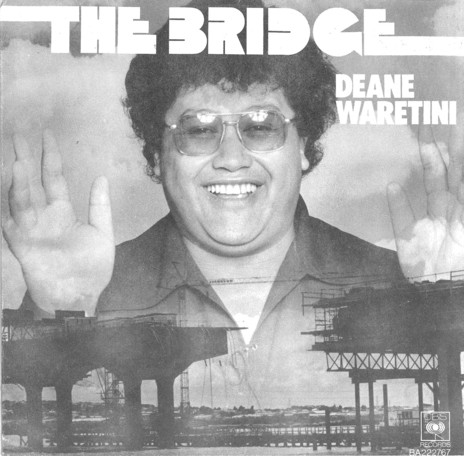

Tait then offered Waretini a new song, ‘The Bridge’. It was a reworking of ‘Il Silencio’, an instrumental released by Italian trumpeter Nini Rosso that had become a regular fixture in Prince Tui Teka’s setlist.

Waretini made it his closing number, but his initial attempts to record it were stymied by the industry belief that a Māori-language song would never sell.

He would later claim the song’s lyrics took him back to his childhood and diving off the bridge in Whakarewarewa to collect the coins tossed by tourists. He also related it to the piles of the Auckland Harbour Bridge and a metaphorical bridging of cultures.

Regardless, “It’s a very sad, haunting song,” he says. “It’s about the piles which are constantly pounded by waves and tides while everyone ignores them ... as a Māori I look at things differently, to me everything is alive and that includes bridge piles.”

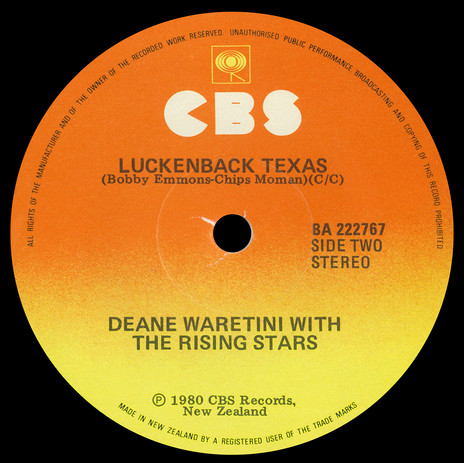

But it wasn’t until 1980 that he got his backing band, The Rising Suns – a blend of The Radars and musicians from the Blind Institute – to record the song in a studio based in a country singer’s West Auckland garage. The solo was played by Kevin Furey, Quincy Conserve’s trumpet player, who was married to Tait’s niece.

In lieu of cash the musicians played for KFC. “We recorded it just as we played it in the hotels,” said Waretini, “with heart and soul and feel. We’d been playing it for a few years so we’d ironed out the rubbish, it had a real spirit to it.”

He then spent $96 to get a stack of singles pressed on Innovation Records, and sent copies to 1ZB before bombarding them with requests to play it.

This was flax-roots marketing. The track was somehow playlisted at Auckland’s Civic Theatre as part of their intermission entertainment and Waretini paid a Queen Street newspaper boy $1 to sell them for 50c each. It worked and music shops began noticing people walking in to ask for “that bridge song”.

The momentum saw the local branch of CBS Records reissue it and on 3 April 1981 ‘The Bridge’ took the No.1 spot from John Lennon’s ‘Woman’, and remained in the New Zealand charts for 14 weeks.

Not only was it the first Māori language track to top the charts, beating Tui Teka’s ‘E Ipo’ by 15 months, it was also the first to go gold.

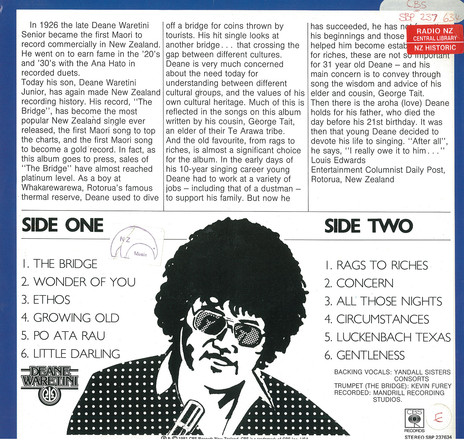

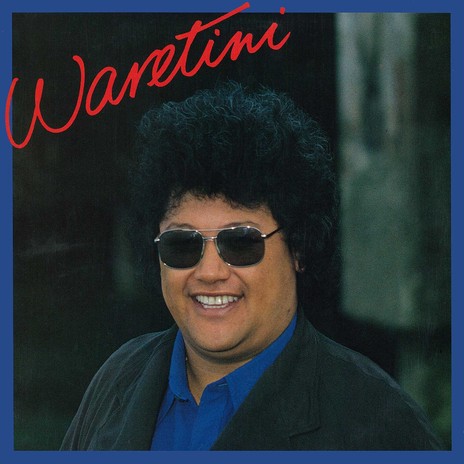

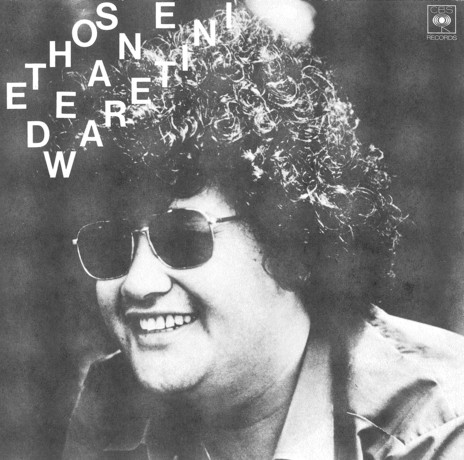

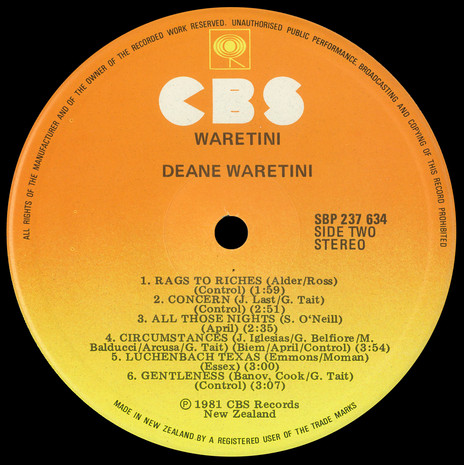

CBS went on to release his debut album, Waretini and three follow-up singles ‘Growing Old’, ‘Ethos’, and ‘Hope’, but none of these releases enjoyed the success of ‘The Bridge’.

If the hit opened new opportunities, Waretini became bitter, thinking CBS had taken advantage of him. He says he was given a lump sum, and surrendered all rights to the recording. (Waretini remembers it being $27,000 – but the sales figures suggest income from the song was much lower. The biggest single of the year, ‘Counting the Beat’, sold 12,500 copies.)

“They gave me a cheque for the lot and I remember I was really frightened, I’d never seen that sort of money. I thought I might go crazy.”

However Tait, after refusing a cut, managed to convince him to put the money on his mortgage – but died soon after. Waretini placed their gold record on his coffin. “I learned a lot from George, especially about giving. I’m a bit of a taker, but I think giving is much better, and that song he gave me, well, I think it brings out a sense of pride in the people of New Zealand. It really did bridge the cultural gap.”

Without Tait’s guidance, Waretini’s career quickly faltered.

First, his national Whirlwind tour in late 1981 was cancelled after only two shows, leaving him heavily in debt.

In 1982 he tried to launch a talent quest carrying his name but it too fell apart after disagreements over money. In 1983 he tried touring again, this time focusing on small town hotels, but low turnouts saw his band walk out.

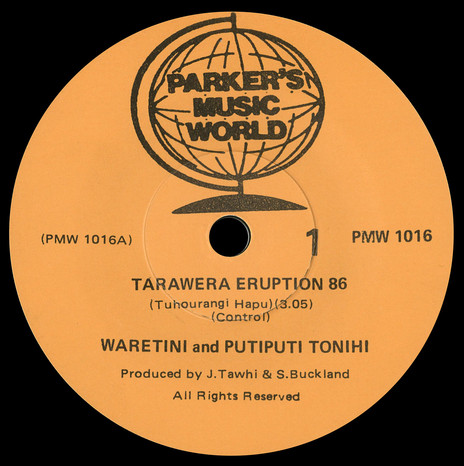

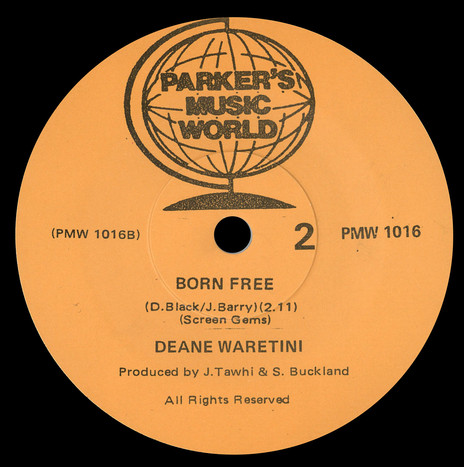

Bankrupt, he went into Reel Vision studio in Manukau City to record a single that he hoped would cover his $17,000 debt. The track, ‘Te Ariki, Oh Lord’, was arranged by James Tawhai from the Radars, who had recently charted with ‘That Lucky Old Sun’.

It didn’t work so well, but as ever Waretini was undeterred. Talking to the Auckland Star he said, “Me? I don’t worry. I let the other fulla worry. Sure, some people may think I’m a washed-up reject because I owe some turkey money, but I’m proud to be a Māori, proud to be New Zealander and proud to have done what I’ve done.”

He later moved to Christchurch where he became a taxi driver while performing the occasional gig.

His star briefly rose again in 2012 when he starred in a seven-part comedy documentary, Now is the Hour, on Māori Television.

Made by the same team who put together Wayne Anderson – Singer of Songs, the show was a pathos-heavy mockumentary of Waretini’s mostly fictional attempt at rekindling his former glory. A follow-up album, Now Is The Hour, spent two weeks in the New Zealand charts, peaking at No.25. The new version of the timeless title track has a rocked-up backing reminiscent of T.Rex.

--

Thanks to Radio New Zealand